Patterns of Commuting for Work a Case Study of Kochi City

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cities » Kochi

Cities » Kochi Published: November 20, 2013 11:32 IST | Updated: November 20, 2013 11:32 IST Vyttila-Kakkanad boat service launched Staff Reporter The new boat service launched on the Vytilla Mobility Hub-Kakkanad route passes under the Kaniampuzha bridge in Kochi on The Hindu Tuesday. Photo: H. Vibhu Proposal to operate water buses on city’s waterways to be submitted to Centre Navigable waterways in and around the city will buzz with faster and more comfortable boats in 2014, since Kochi Metro Rail Limited (KMRL) has readied a Rs 40-crore project for the purpose. “The proposal to operate water buses will soon be submitted to Union Urban Development Ministry to source JNNURM funds and a formal nod is expected within three months. Work on procuring the boats can begin by March,” said Elias George, MD of KMRL and Chairman of Unified Metropolitan Transport Authority (UMTA). He was speaking at a function organised here to flag off State Water Transport Department’s (SWTD) Vyttila Mobility Hub-Kakkanad boat service. “Our aim is to introduce catamaran-type fibre-reinforced-plastic boats, which are delivered within a few months of the order being placed. Being lighter and faster than steel boats, they can cover the Vyttila-Kakkanad distance in 12 minutes,” Mr George said. In his inaugural address, Union Minister of State for Food and Public Distribution K.V. Thomas said that Kerala’s water transport sector must be brought out of the red. “The Kollam-Kottapuram National Waterway III has tremendous potential to transport cargo.” Kochi Metro alone might not be able to decongest the city. -

Newsletter Govt

12 DEC 2018 Newsletter Govt. Of Kerala Kudumbashree Mission ties up with KMRL for supplying food in steel boxes udumbashree Mission ties up with Kochi Metro separate to different metro stations to distribute the food. KRail Limited (KMRL) for supplying homely food Kudumbashree members are permitted to travel on metro in steel boxes to the employees of Kochi Metro. Its on trains free of cost for distributing the food. As of now, getting inspired from the Dabbawalas of Mumbai, that they are sticking on to the usual meals for lunch but the dabbawala service of Kudumbashree is launched.The on progressing, they plans to provide more options as freshly prepared homely food is packed in steel boxes well. The dabba system stands out unique that only Rs (dabbas) and are distributed to the employees of Kochi 40 is charged per meal which includes rice with sambar, Metro. The service was launched during the last week curd, and fish curry or fry or chicken curry. The steel of November 2018. It is Kudumbashree Mission’s Micro boxes are later collected and are brought back to the Enterprise-Samrudhi Catering based at Choornikkara Micro Enterprise unit. The unit is now distributing food panchayath, Aluva of Ernakulam district, which prepares in 100 dabbas now. food for the employees and supplies the same among the Kochi Metro is maintained environment KMRL employees across the 16 Metro stations in Kochi. friendly. The dabbawala system was implemented to The lunch orders are placed by the Kochi discourage the employees from bringing food in plastic Metro employees before 10 AM everyday and once the containers and with the launch of the dabbawala system, food is prepared, the Kudumbashree members gather there has been a decrease of plastic waste across all the K with their dabbas at Muttom station from where they 16 metro stations. -

Item No.01 1.Perused the Judgment of Hon'ble STAT in MVAA No.162

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF REGIONAL TRANSPORT AUTHORITY ERNAKULAM HELD ON 23/02/2017 Present:- Chairman- Sri.K.MUHAMMED.Y.SAFEERULLA,I.A.S, The District Collector, Ernakulam Members:- Sri.K.G.Samuel, Deputy Transport Commissioner [Law], CZ- II,Ernakulam. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Item No.01 1.Perused the judgment of Hon’ble STAT in MVAA No.162/2016 dtd 17/11/2016. 2.Heard; Adv.Gopinathan Nair, the learned counsel represented the applicant Sri. Shibu.C.S. In view of the direction issued by the Hon’ble State Transport Appellate Tribunal, this authority verified the records in detail. This is the application for the grant of regular permit in respect of stage carriage KL-07-AK-4789 or a suitable stage carriage o the route Manjapra- Vyttila Mobility Hub via Angamaly, Mekkad, KAMCO Jn, Athani, Manjaly, Vedimara Jn, Peruvaram temple Road, Chithranjaly Theatre Jn, North Parur, Koonammavu, Varappuzha Bridge and Edappally Byepass as ordinary Moffusil Service. This authority in its earlier sitting held on 05/04/2016 considered the application and rejected the same on the basis of reports of the Secretary, North Parur Municipality and enquiry officer in the Motor Vehicles Department regarding the non feasibility of operation of stage carriages on the portion between Peruvaram temple road and Chithranjali Jn. Aggrieved of the above decision, the applicant filed an appeal before the State Transport Appellate Tribunal. Vide judgment in MVAA No.162/2016 dtd 17/11/2016, the STAT allowed the appeal and directed the RTA to remand back the matter on the findings that while rejecting the application, the RTA mainly relied on the report submitted by the Assistant Engineer, North Parur and There is nothing on record to indicate that the road is not feasible for other operators well, No restriction is also imposed under Section 115 of the MV Act by issuing notification. -

BID SYNOPSIS 1 Tender No. : 05/VMHS/A1/285/2020-21

BID SYNOPSIS 1 Tender No. : 05/VMHS/A1/285/2020-21 Name and Managing Director, Vyttila Mobility Hub Society, 2 address of : Sreevalsam, IInd Floor, RSAC Road, employer Vyttila.P.O, Kochi-19 Name of Establishing , Operation and Maintenance of Commercial space for Kiosk 3 : Service at Vyttila Mobility Hub Place of Vyttila Mobility Hub, Vyttila in Ernakulam District , Kerala , South 4 : Service India Establishing , Operation and maintenance of Commercial space for Kiosk, having an area of 120 sq.ft in(bay 6) the Bus Terminal at Vyttila Scope of Mobility Hub(commercial space suitable for ATM services, Tea/Snacks 5 : Service counter, juice shop, cafeteria , book stall , etc. Tea/snacks /juices/cafeteria/books etc must be given at reasonable rates acceptable to the Vyttila Mobility Hub Society Period of 6 : One year Service Cost of 7 Tender : Rs. 590/- including GST @18% document Tender Document Managing Director, Vyttila Mobility Hub Society, RSAC Road, 8 : issuing Vyttila.P.O, Kochi-19 authority Pre bid 9 : N.A meeting All working days from 07/06/2021 to 10 Date of issue : of tender 31/07/2021 between 10.A.M to 4 P.M 5 documents Last date of 03/08/2021 on or before 1.00 PM. And opening will be on the same day 11 receipt of : at 3.00 PM tender Place and Vyttila Mobility Hub Society, RSAC Road, Vyttila.P.O, Cochin-19. method of Tender shall be send by Speed/Registered post of Postal Department, 12 : submission Govt. of India only and will not be accepted directly or through courier of tender service Tender Managing Director , Vyttila Mobility Hub Society RSAC Road, Vyttila 13 receiving : P.O, Kochi-19 authority Earnest Rs. -

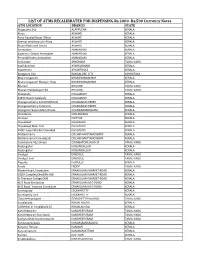

LIST of ATMS RECALIBRATED for DISPENSING Rs.2000

LIST OF ATMS RECALIBRATED FOR DISPENSING Rs.2000 -Rs.500 Currency Notes ATM LOCATION BRANCH STATE Alappuzha 2nd ALAPPUZHA KERALA Aluva ALWAYE KERALA Parur Kavala(Aluva) Offsite ALWAYE KERALA Seemas wedding coln Aluva ALWAYE KERALA Aluva Additional Onsite ALWAYE KERALA Ammadam AMMADAM KERALA Kodannur Center Ammadam AMMADAM KERALA Perumbillissery Ammadam AMMADAM KERALA Arakonam ARKONAM TAMIL NADU Ayarkkunnam AYARKUNNAM KERALA Ayyanthole AYYANTHOLE KERALA Bangalore City BANGALORE-CITY KARNATAKA Bharananganam BHARANANGANAM KERALA Bharananganam Marygiri Hosp BHARANANGANAM KERALA Bhavani BHAVANI TAMIL NADU Bhavani Pallipalayam Rd BHAVANI TAMIL NADU Chalakudy CHALAKUDY KERALA KSRTC Road Chalakudy CHALAKUDY KERALA Changanacherry 2nd ATM(Main) CHANGANACHERRY KERALA Changanacherry Central Jn CHANGANACHERRY KERALA Changaramkulam Main Onsite CHANGARAMKULAM KERALA Chelakkara CHELAKKARA KERALA Chittoor CHITTUR KERALA Chavakkad CHAVAKAD KERALA Chavakkad Main 2nd CHAVAKAD KERALA EMKE Super Market Chavakad CHAVAKAD KERALA Mattancherry COCHIN-MATTANCHERRY KERALA Mattancherry Karuvelipadi COCHIN-MATTANCHERRY KERALA Coimbatore Raja Street COIMBATORE-RAJA ST TAMIL NADU Kodungallur KODUNGALLUR KERALA Kodungallur KODUNGALLUR KERALA Dindigul DINDIGUL TAMIL NADU Dindigul 2nd DINDIGUL TAMIL NADU Elapully ELAPULLY KERALA Erode ERODE TAMIL NADU Market Road, Ernakulam ERNAKULAM MARKET ROAD KERALA GCDA Complex,Ekm(Mkt Rd) ERNAKULAM MARKET ROAD KERALA St Theresas College EKM ERNAKULAM MARKET ROAD KERALA M.G Road-Ernakulam ERNAKULAM M G ROAD KERALA M.G Road, Yuvarani -

Metro-6 (Swami Samarth Nagar-Vikhroli); Rs

URBAN MOBILITY INTERNATIONAL AND INDIAN ACTIVITIES METRO NEWSLETTERS 79 - 87; September 2019 gathered by Dr. F. A. Wingler METRO NEWSLETTERS on “URBAN MOBILITY AS A SERVICE” PUBLIC MULTIMODAL URBAN, SUBURBAN AND INTERURBAN PASSENGER TRANSIT SYSTEMS WITH METRO-BUS, LIGHT-RAIL, TRAM-TRAIN, METRO-RAIL, METRO-TRAIN, REGIONAL RAPID TRANSIT, COMMUTER-RAIL, ROPE-WAY/TRAIN, MAGLEV AND HOVERCRAFT TRANSIT/PEOPLE MOVER, WATER-METRO, AUTONOMOUS PEOPLE-MOVER TRANSPORTATION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS IN MODERN URBAN/MEGAPOLIS ENVIROMENT METRO Newsletter by Dr. F.A. Wingler METRO 77, July 2019 Digitalised Rail World 1 PART I: INDIAN ACTIVITIES AND INITIATIVES FOR URBAN MOBILITY AS A SERVICE Exclusive Interview with Mr. Thiruman Archunan, Director – Projects, Kochi Metro Rail Limited, on Progress of Kochi Metro; India June 28, 2019 Interviews Mr. Thiruman Archunan, Director – Projects, Kochi Metro Rail Limited, is in charge of all Civil works related to KMRL (Kochin Metro Rail Limited): Construction of metro stations, viaduct, track, depot, and others works related to Roads, improvements to city landscape, Place making and other NMT (Non-Motorised Transport) related works, modernised ferry services etc“. Rail Analysis: What is the current Progress of Kochi Metro? Mr. Thiruman Archunan: The approved Phase-I of Kochi Mero Rail is from Aluva to Petta is 25.16 km with 22 stations. The stretch from Aluva to Palarivattom with 13.26 km is operational from June 2017 and up to Maharajas with total 18.22 km is operational from October 2017. 2 Balance stretch of 6.94 km from Maharajas College to Petta is passing through the Central Business District (CBD) of Kochi City touching the major Railway Station Ernakulam South and Vytila, the busiest junction of Ernakulum, Kerala. -

Greater Cochin Development Authority, Kochi – 20 Administration Report for 2016-17

GREATER COCHIN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY, KOCHI – 20 ADMINISTRATION REPORT FOR 2016-17 INTRODUCTION As a first step towards the formalized development planning of the Cochin region, an advisory committee was set up in 1965. In the same year itself, a Joint Town Planning Committee was constituted for their planning & development and this committee has been elevated into a trust viz. Cochin Town Planning Trust under the Chairmanship of the District Collector. In the course of time, the authorities were convinced of the fact that a larger set up is required to control the growth of the Cochin City and its environs in a planned manner which resulted in the formation of GCDA in the year 1976. The Greater Cochin Development Authority came into existence on 24.1.1976 under the Madras Town Planning Act of 1920 and Travancore Town Planning Act IV of 1108 read with G.O. (MS) No.19/76/LA & SWD dated 23.1.1976. Whereas in exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) of section 51 of the Kerala Town and Country Planning Act, 2016 (9 of 2016), The Greater Cochin Development Authority has been constituted as per notification issued under G.O(P) No. 47/2016/LSGD dated 16th December 2016 and published as SRO No. 756/2016 in the Kerala Gazette Extraordinary No. 2180 dated 16th December 2016. This is a body coming under the Local Self Government Department of the Kerala and now guided by clause 51-60 of Kerala Town and Country Planning act 2016 vide notification 19904/Leg C1/2013/Law dated 17th March 2016. -

Disinvestment of IFCI's Equity Shares in KITCO Limited

Disinvestment of IFCI’s equity shares in KITCO Limited (KITCO) REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL IFCI Tower 61, Nehru Place New Delhi 110 019 Date of Issue: December 31, 2015 Last Date of Submission: January 27, 2016 upto 1400 hours (IST) REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL FOR DISINVESTMENT OF EQUITY SHARES IN KITCO ________________________________________________________________________ 1. Background 1.1 IFCI Limited (IFCI) is the oldest Development Financial Institution of the country set-up in 1948 as a statutory corporation under Industrial Finance Corporation Act, 1948 (IFC Act) for providing medium and long-term finance to the industrial sector. In 1993, after the repeal of IFC Act, IFCI became a public limited company registered under the Companies Act, 1956. Pursuant to conversion of Government of India’ loan/grant aggregating to Rs. 923 crore to IFCI into equity shares of IFCI and acquisition of preference shares of IFCI from Banks by Government of India, IFCI has become a Government Company with effect from 7th April, 2015 in terms of Section 2(45) of Companies Act, 2013 with Government of India’s shareholding of 51.04% of its total paid up share capital. IFCI is also registered with Reserve Bank of India (RBI) as a Systemically Important Non-Deposit taking Non-Banking Finance Company (NBFC-ND-SI). The primary business of IFCI is to provide medium to long-term financial assistance to the manufacturing, services and infrastructure sectors. 1.2 IFCI and other All India/ State Level Financial Institutions along with Public Sector Banks had set-up Technical Consultancy Organizations (TCOs) in the 1970s in various States across the country in order to cater to the consultancy needs of small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and for giving pace to industrialization with the objectives of facilitating overall industrial development of the country. -

Imprint of a Unique Friendship Salute to Our Own Message Voice - Jwaladhwani

50Golden years Imprint of a Unique Friendship Salute to our own Message voice - JwalaDhwani In early 1980s, when many of us joined Kochi Refinery, our house journal was one of the foremost communication tools in the company. Working in the shifts, I used to eagerly wait for getting hold of the issues every first week of the month. It was through the magazine that we came to know about the developments in the company. It brought to light the literary talents of many of our colleagues and we enjoyed reading their poems, stories and other articles. Through the magazine we came to know about many of our colleagues and their musings. In many ways, those years were the golden age of magazines. Magazines as India Today, The Illustrated Weekly of India and Readers Digest were having a heyday. ‘The Week’ that came out from Kochi started its publication in the early 1980s. Thanks to libraries like ours, many of us got a chance to savour international publications as Time, Newsweek and The Economist. No wonder, in those years I saw CR Newsletter also transforming in to a magazine which could match any other general publication with all content categories as letters, news stories, features, and even horoscope. I recall the newsletter having a new avathar as JwalaDhwani. I recall JwalaDhwani in its new house-style. I recall the magazine going in full colour. Recently, during the Golden Jubilee celebrations of BPCL Kochi Refinery I had gone through some pages of JwalaDhwani in the 1960s and 70s. It particularly stuck me that the newsletter was published for the very first time mainly for sensitizing employees about the importance of safety. -

Asset Greenford Single Pages.Ai

Ernakulam Town Madhava Pharmacy Madhava Maharajas College Nehru Stadium Kaloor Ernakulam Junction Palarivattom GCDA Elamkulam Edappally Jn. Vyttila Mobility Hub Pathadipalam Thaikoodam CUSAT Petta Alliance Junction Kalamassery S N Junction Muttom Tripunithura Companypady Aluva Pulinchodu stay connected 51stst Project 01 FROM THE LAND OF THE RIVER, TO THE THRESHOLD OF CONNECTIVITY. We welcome you to the land renowned for Sivarathri festival and as the summer residency of the Travancore Royal Family. It’s proximate to Kochi and provides linkages with major districts of North and South Kerala. Aluva is poised to become the next most preferred and growing destination that facilitates quick and easy access to Kochi. Live comfortably in the delightful surroundings of Aluva and be on the threshold of connectivity. STAY CONNECTED TO TOMORROW’S METRO 02 ESTABLISH LIGHTNING CONNECTIVITY. ENJOY LIESURELY LIFE Asset Homes, Kerala’s most awarded builder and the first builder in India to have three CRISIL 7 STAR rated residential projects, presents its most novel living concept with Asset Greenford. The project explores the advantages of the Kochi Metro Rail project in the domain of convenient and quick transportation. Asset Greenford is about two specific advantages; lightning connectivity and leisurely life. STAY CONNECTED TO TOMORROW’S METRO 03 Building No: B.A.93/08.09 STAY AWAY FROM CITY’S HASSLES. STAY CONNECTED WITH CITY’S DAZZLES. Asset Greenford is coming up in prime land at Pulinchode, Aluva in the vicinity of the Pulinchode Metro Station. The luxury apartment project has 16 floors with 70 apartments in 2BHK and 3BHK formats. STAY CONNECTED TO LUXURIES 04 51stst Project 05 STAY CONNECTED Asset Greenfordeenford emergesemerges rightright at PulinchodePulinchode metro station, Aluva,Aluva, blazes thee trailtrail ofof fastfast progressprogress throughthrough bringingbringing allall conveniences and luxuriesries at arms length.length. -

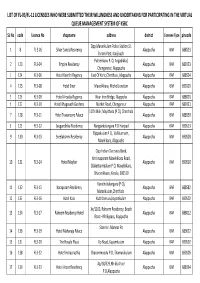

List of Fl-03/Fl-11 Licensees Who Were Submitted Their Willingness and Undertaking for Participating in the Virtual Queue Management System of Ksbc

LIST OF FL-03/FL-11 LICENSEES WHO WERE SUBMITTED THEIR WILLINGNESS AND UNDERTAKING FOR PARTICIPATING IN THE VIRTUAL QUEUE MANAGEMENT SYSTEM OF KSBC SL No code Licence No shopname address district Licensee Type pincode Opp.Mararikulam Police Station,S L 1 8 FL 3 26 Silver Sands Residency Alappuzha BAR 688523 Puram Post, Kanjikuzhi Puthenkavu P. O, Angadikkal, 2 123 FL3-04 Empire Residency Alappuzha BAR 689123 Chengannur, Alappuzha 3 124 FL3-06 Hotel Keerthi Regency East Of Ksrtc,Cherthala ,Alappuzha Alappuzha BAR 688524 4 125 FL3-08 Hotel Sixer Mavelikkara, Michel Junction Alappuzha BAR 690101 5 126 FL3-09 Hotel Arcadia Regency Near Iron Bridge, Alappuha Alappuzha BAR 688001 6 127 FL3-10 Hotel Bhagavath Gardens Market Road, Chengannur Alappuzha BAR 689121 11Th Mile, Mayithara (P O), Cherthala 7 128 FL3-11 Hotel Travancore Palace Alappuzha BAR 688539 . 8 129 FL3-12 Saugandhika Residency Nangiarkulangara P.O Haripad Alappuzha BAR 690513 Elippakulam P O,. Vallikunnam,. 9 130 FL3-13 Sreelakshmi Residency Alappuzha BAR 690503 Mavelikara, Alappuzha Opp Indian Overseas Bank, Krishnapuram Mavelikkara Road, 10 131 FL3-14 Hotel Mayfair Alappuzha BAR 690510 Olakettiambalam P.O, Mavelikkara, Bharanikkavu, Kerala, 690510 Kanichukulangara (P O), 11 132 FL3-15 Karapuram Residency Alappuzha BAR 688582 Mararikulam,Cherthala . 12 133 FL3-16 Hotel Kalai Kuttitheruvu,Kayamkulam Alappuzha BAR 690502 Xx/1100, Raheem Residency, Beach 13 134 FL3-17 Raheem Residency Hotel Alappuzha BAR 688012 Road - Nh Bypass, Alappuzha Store Jn. Mannar Po 14 136 FL3-19 Hotel Maharaja Palace Alappuzha BAR 689622 15 137 FL3-20 The Royale Plaza Kp Road, Kayamkulam Alappuzha BAR 690502 16 138 FL3-22 Hotel Indraprastha Charummoodu P.O, Thamarakulam Alappuzha BAR 690505 Ap/18/329,Nh 66,Aroor 17 139 FL3-23 Hotel Aroor Residency Alappuzha BAR 688334 P.O,Alappuzha SL No code Licence No shopname address district Licensee Type pincode The Esquire Inn, Kp Road, Charumood 18 140 FL3-24 The Esquire Inn Alappuzha BAR 690505 Po, Alapuzha District 19 141 FL3-25 Hotel Indraprastha Kayamkulam, Near Private Bus Stand. -

Vytilla Mobility Hub: a Gateway to Kerala

Vytilla Mobility Hub: A Gateway to Kerala CII- Kerala|Centre for Public Policy Research| Kumar Group 1 1. Introduction Kochi, the commercial capital of Kerala, is one of the fastest growing two-tier metropolitan cities in India with a population of 13.55 lakh, including the Kochi Urban Agglomeration (KUA).1 The Kochi Urban Agglomeration comprises of Kochi Municipal Corporation, five municipalities, 15 Panchayats and a part of three Panchayats. The city has an area of 94.88 sq. km. Urban expansion during the past few decades outgrew the limits of Kochi City. The immediate hinterland of Kochi Port has been delineated as the Greater Kochi Region, which covers 731 sq. km- almost eight times the area of the city. According to a study, the city has seen a real estate growth of 30 per cent on a yearly basis for the last couple of years and has a GDP growth rate of 8.3 per cent2. Kochi is seen as one of the top three IT/ITES commercial real estate destinations and the availability of 15 Giga bytes bandwidth, through undersea cables ensures seamless data flow and lower operational costs, compared to other major cities in India. Moreover, some very important port-oriented developments are being planned in the city such as the Vallarpadam Transshipment terminal, the LNG terminal at Puduvipe, the SBM of KRL at Vypin, and the SEZ at Vypin. Thus, it goes without saying that Kochi is bound to see a fair amount of commercial investment and development in the years to come. According to the City Development Plan of the Corporation of Kochi, investments to the tune of Rs 15,000 crore are expected to come in the next five years.