Senate Inquiry Into Regional Inequality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of Ordinary Council

ORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL MINUTES 16 JANUARY 2019 ORDINARY COUNCIL MEETING MINUTES 16 JANUARY 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Subject Page No. Table of Contents ........................................................................................................ 2 1.0 Meeting Opened ........................................................................................................ 5 2.0 Leave of Absence ...................................................................................................... 5 3.0 Condolences/Get Well Wishes ................................................................................. 5 3.1 Condolences/Get Well Wishes ...................................................................................... 5 4.0 Declaration of any Material personal interests/conflicts of interest by councillors and senior council officers ................................................................... 6 5.0 Mayoral Minute .......................................................................................................... 7 6.0 Confirmation of Minutes ........................................................................................... 8 6.1 Confirmation of Ordinary Meeting Minutes 12 December 2018 ..................................... 8 7.0 Business Arising from Minutes ................................................................................ 9 8.0 Committee Reports ................................................................................................. 10 8.1 Receipt of the Minutes -

Lockyer Valley Region Walking Routes

What is 10,000 steps? Walking Checklist The 10,000 steps program aims to increase the daily activity of residents across the Lockyer Valley region. Ensure you have comfortable walking shoes Wear light coloured clothing, broad brimmed hat and The 10,000 steps goal puts a focus on being active the apply sunscreen (SPF 30+) entire day. To help you make active choices, this program encourages participants to use a pedometer to remind you If possible walk during early morning and evening to how many or how few steps you have taken during the day. avoid the heat of the day Walk with others to improve safety in areas that are Achieving 10,000 steps in a day is the recommended goal less populated for a healthy adult. It may sound like a lot of steps but if you can make a conscious effort to increase your steps Have some water before you go and take a water bottle during the day the task will become much simpler. with you, continually sipping along the way Work up to a moderate pace (slight but noticeable Lockyer Valley Region increase in breathing and heart rate) STEPS PER DAY ACTIVITY LEVEL Slow down if you feel out of breath or uncomfortable Walking routes < 5000 inactive If you have chest discomfort or pain while being active 5000-7499 low active stop immediately and seek medical advice 7500-9999 somewhat active Stretch after exercise ≥ 10,000 active Active Healthy Lockyer ≥ 12,500 highly active For further information about the 10,000 steps program and The benefits of walking Active Healthy Lockyer visit www.lockyervalley.qld.gov.au. -

Ordinary Meeting of Council Minutes 11 December 2019

ORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL MINUTES 11 DECEMBER 2019 ORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL MEETING 11 DECEMBER 2019 MINUTES TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Subject Page No. 1.0 Meeting Opened........................................................................................................................... 5 2.0 Leave of Absence .......................................................................................................................... 5 3.0 Condolences/Get Well Wishes ...................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Condolences/Get Well Wishes....................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Declaration of any Material personal interests/conflicts of interest by councillors and senior council officers ................................................................................................................... 7 5.0 Mayoral Minute ........................................................................................................................... 8 6.0 Confirmation of Minutes ............................................................................................................... 9 6.1 Confirmation of Ordinary Meeting Minutes 27 November 2019 .................................................. 9 7.0 Business Arising from Minutes ...................................................................................................... 9 8.0 Committee Reports ..................................................................................................................... -

Minutes of Ordinary Council

ORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL MINUTES 26 FEBRUARY 2020 ORDINARY MEETING OF COUNCIL MEETING 26 FEBRUARY 2020 MINUTES TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Subject Page No. 1.0 Meeting Opened........................................................................................................................... 4 2.0 Leave of Absence .......................................................................................................................... 4 3.0 Condolences/Get Well Wishes ...................................................................................................... 5 3.1 Condolences/Get Well Wishes....................................................................................................... 5 4.0 Declaration of any Material personal interests/conflicts of interest by councillors and senior council officers ................................................................................................................... 6 5.0 Mayoral Minute ........................................................................................................................... 6 6.0 Confirmation of Minutes ............................................................................................................... 7 6.1 Confirmation of Ordinary Meeting Minutes 12 February 2020 ..................................................... 7 7.0 Business Arising from Minutes ...................................................................................................... 8 8.0 Committee Reports ..................................................................................................................... -

Investigation of Scour Mitigation Methods for Critical Road Structures

University of Southern Queensland Faculty of Engineering and Surveying Investigation of Scour Mitigation Methods for Critical Road Structures A dissertation submitted by Peggy Chou Pei-Chen in fulfilment of the requirements of ENG4111 and ENG4112 Research Project towards the degree of Bachelor of Engineering (Honours) (Civil) Submitted October, 2016 Supervisor: Weena Lokuge and Buddhi Wahalathantri i Abstract The flood events that occurred in 2011 and 2013 in Queensland are notable for their devastating outcomes and damages to critical road structures. Bridges are necessary for the local community to travel and provide disaster relief during times of need. Therefore, it is important to identify methods that prevent bridge scour. To identify these countermeasures, a literature review of critical infrastructure scour prevention method was conducted. Methods that are appropriate were then analysed using the hydraulics software HEC-RAS. The Tenthill Creek Bridge was chosen as the framework of the analysis. Bridge scour depths were modelled and each method was compared. Combined with the HEC-RAS analysis, the feasibility analysis shows that a combination of collaring, riprap and wing walls is the most cost effective in decreasing the scour depths at piers and abutments. ii University of Southern Queensland Faculty of Engineering and Surveying ENG4111 Research Project Part 1 & ENG4112 Research Project Part 2 Limitations of Use The Council of the University of Southern Queensland, its Faculty of Engineering and Surveying, and the staff of the University of Southern Queensland, do not accept any responsibility for the truth, accuracy or completeness of material contained within or associated with this dissertation. Persons using all or any part of this material do so at their own risk, and not at the risk of the Council of the University of Southern Queensland, its Faculty of Engineering and Surveying or the staff of the University of Southern Queensland. -

Agricultural Needs Analysis (August 2018)

RDA Ipswich & West Moreton AGRICULTURAL NEEDS ANALYSIS TRANSFORMING A REGION August 2018 Kilcoy Esk Regional Development Australia Ipswich & West Moreton would like to acknowledge the traditional owners of our region – The Jagera, Kitabul, Ugarapul, Yugambeh and Yuggera people. Gatton Ipswich Laidley Springfield Lakes Disclaimer – Whilst all efforts have been made to ensure the content of this Boonah Beaudesert publication is free from error, the Regional Development Australia Ipswich & West Moreton (RDAIWM) Ipswich and West Moreton Agricultural Needs Analysis does not warrant the accuracy or completeness of the information. RDAIWM does not accept any liability for any persons, for any damage or loss whatsoever or howsoever caused in relation to that person taking action (or not taking action as the case may be) in respect of any statement, information or advice given in this publication. 2 RDAIWM Agricultural Needs Analysis AUG 2018 Chair’s Message As there is no single entity to bring together becoming better informed about the food they the various needs and wants for the future are eating and taking a more significant interest development of the agricultural industry of in its provenance and qualities. the four Councils of the West Moreton region Similarly, the increasing pressures of living in a (Ipswich, Somerset, Lockyer Valley and Scenic global city, as Brisbane is becoming, engenders Rim), Regional Development Australia Ipswich & a desire for respite. West Moreton (RDAIWM) has undertaken a high- level review of the vital infrastructure and policy The SEQ Regional Plan categorises most of development needs of the region. the study as: “Regional Landscape and Rural ongoing existing lists of considered, critical Production” for precisely this reason: to provide infrastructure priorities. -

Water Netserv Plan Overview and Guide

WATER NETSERV PLAN OVERVIEW AND GUIDE ENRICH QUALITY OF LIFE URBAN UTILITIES STRATEGIC PLANNING – OUR VISION TO OUR CUSTOMERS As a business, Urban Utilities has defined that Our Purpose is to Enrich quality of life. Our Vision is to play a valued role in enhancing the liveability of our communities. A key element in delivering on these promises is the role that Urban Utilities plays in delivering high quality water services and facilitating growth across South East Queensland. The Water Netserv Plan (Part A) (Netserv Plan) outlines the scope of services that will be provided to our retail customers, in addition to the standard of service outcomes and how these services will be charged. The Netserv Plan also provides developers with a summary of the planning assumptions, including population growth, of each of the Council regions QUU services. These outline the expectations for the scope and location of future growth across the region and the anticipated capital investment program to accommodate this expansion. For each of the Stakeholder Councils, the Netserv Plan outlines the business processes Urban Utilities will use to deliver on the growth ambitions identified in each of the Planning Schemes. Collectively, the outcomes from the Netserv Plan outline both what Urban Utilities intends to deliver and the business processes for how these outcomes will be achieved. Urban Utilities Water Netserv Plan 1 2 Urban Utilities Water Netserv Plan CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 1. URBAN UTILITIES 6 1.1 Who we are 6 1.2 Our stakeholdres 6 1.3 What we do 6 1.4 Our Customer Charter 7 1.5 Our Operating Environment 7 1.6 Water Demand Management 9 1.7 Water Consumption Trends 9 1.8 Water Supply Network 9 1.9 Capacity of Infrastructure Networks 9 2. -

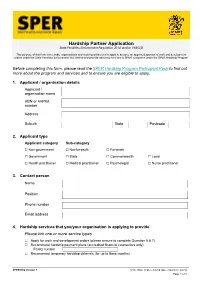

SPER Hardship Partner Application Form

Hardship Partner Application State Penalties Enforcement Regulation 2014 section 19AG(2) This purpose of this form is to enable organisations and health practitioners to apply to become an approved sponsor of work and development orders under the State Penalties Enforcement Act 1999 and/or provide advocacy services to SPER customers under the SPER Hardship Program Before completing this form, please read the SPER Hardship Program Participant Pack to find out more about the program and services and to ensure you are eligible to apply. 1. Applicant / organisation details Applicant / organisation name ABN or AHPRA number Address Suburb State Postcode 2. Applicant type Applicant category Sub-category ☐ Non-government ☐ Not-for-profit ☐ For-profit ☐ Government ☐ State ☐ Commonwealth ☐ Local ☐ Health practitioner ☐ Medical practitioner ☐ Psychologist ☐ Nurse practitioner 3. Contact person Name Position Phone number Email address 4. Hardship services that you/your organisation is applying to provide Please tick one or more service types ☐ Apply for work and development orders (please ensure to complete Question 6 & 7) ☐ Recommend hardship payment plans (accredited financial counsellors only) FCAQ number ☐ Recommend temporary hardship deferrals (for up to three months) SPER6002 Version 1 ©The State of Queensland (Queensland Treasury) Page 1 of 8 5. Locations where you/your organisation will provide these services ☐ All of Queensland or Select Local Government Area(s) below: ☐ Aurukun Shire ☐ Fraser Coast Region ☐ North Burnett Region ☐ Balonne -

2019 Queensland Bushfires State Recovery Plan 2019-2022

DRAFT V20 2019 Queensland Bushfires State Recovery Plan 2019-2022 Working to recover, rebuild and reconnect more resilient Queensland communities following the 2019 Queensland Bushfires August 2020 to come Document details Interpreter Security classification Public The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you have Date of review of security classification August 2020 difficulty in understanding this report, you can access the Translating and Interpreting Authority Queensland Reconstruction Authority Services via www.qld.gov.au/languages or by phoning 13 14 50. Document status Final Disclaimer Version 1.0 While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no QRA reference QRATF/20/4207 responsibility for decisions or actions taken as a result of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained within. ISSN 978-0-9873118-4-9 To the best of our knowledge, the content was correct at the time of publishing. Copyright Copies This publication is protected by the Copyright Act 1968. © The State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority), August 2020. Copies of this publication are available on our website at: https://www.qra.qld.gov.au/fitzroy Further copies are available upon request to: Licence Queensland Reconstruction Authority This work is licensed by State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority) under a Creative PO Box 15428 Commons Attribution (CC BY) 4.0 International licence. City East QLD 4002 To view a copy of this licence, visit www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Phone (07) 3008 7200 In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt this annual report, as long as you attribute [email protected] the work to the State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority). -

Lockyer Valley

Community Profiles – Lockyer Valley Health needs and service issues summary Population expected to more than double in the next 20 years. Ageing population, with 43% of the region’s population aged 45+. Laidley Health Service has a 6% self-sufficiency, meaning the hospital serviced 6% of their catchment’s public hospital demand. Highest rates of patient outflows outside of West Moreton for Laidley are to Metro South and Darling Downs Hospital and Health Services. West Moreton Health’s 15-year master plan identifies short to medium term infrastructure priorities including minor refurbishments to Laidley Health Service. About Lockyer Valley Figure 8, Lockyer Valley planning region population Lockyer Valley planning area consist of three SA2 areas: breakdown by age, 2017 • Lockyer Valley - East • Lowood • Rosewood Lockyer Valley covers a land area of 2,034 square kilometers and contains 48,594 residents or 17% of West Moreton’s total resident population. Figure 8 shows a breakdown of population by age group, showing significant numbers of both young (0-14) and older (65+) people in the region. Page 9 of 60 Community Profiles Report 2019 Demographics Health services The Lockyer Valley includes the Laidley Health Laidley Hospital cannot support the health needs of the Service, which is located 45kms west of Ipswich. community in isolation and works in collaboration with Laidley Health Service has an inpatient bed capacity of a range of primary care and community-based health 15 physical beds and three beds in emergency. professionals to provide care to the Lockyer Valley community. Laidley Health Service is a level 2 Clinical Services Capability Framework (CSCF) hospital. -

Lockyer Valley Regional Council Submission to the Australian Government Productivity Commission Inquiry Into Natural Disaster Funding Arrangements 6 June 2014

Lockyer Valley Regional Council Submission to the Australian Government Productivity Commission Inquiry into Natural Disaster Funding Arrangements 6 June 2014 The Lockyer Valley Regional Council welcomes the opportunity to provide a submission to the Productivity Commission’s inquiry into Natural Disaster Funding Arrangements. Lockyer Valley Regional Council is a medium sized local government in Queensland that has had media coverage in recent years regarding flooding and has been directly impacted by natural disaster and views this submission as an opportunity to provide practical and real examples of what has been successful and what hasn’t and further considerations that warrant review in the overall disaster management framework. Council is a member of the Local Government Association of Queensland and the Council of Mayors for South East Queensland. About Council Lockyer Valley Regional Council was formed in March 2008 following the amalgamation of the former Gatton and Laidley Shire Councils as part of sweeping State Government reforms. Nestled at the foot of the Great Dividing Range, the Lockyer Valley is little more than an hour’s drive from Brisbane and the Gold Coast and approximately 30 minutes from Ipswich and Toowoomba. Renowned for its rural landscape, the Lockyer Valley is the perfect destination for people looking to escape the city rat race for the day or to relax and unwind at one of the many boutique B & B’s or farm stays. There are a number of locations within the Lockyer Valley serviced by major centres of Gatton, Laidley and Plainland. There were approximately 36,404 people residing in the Lockyer Valley in 2012. -

PRELIMINARY LITERATURE REVIEW ECONOMIC RECOVERY and RESILIENCE in a REGIONAL LABOUR MARKET (Recovery and Resilience Project)

PRELIMINARY LITERATURE REVIEW ECONOMIC RECOVERY AND RESILIENCE IN A REGIONAL LABOUR MARKET (Recovery and Resilience Project) A project undertaken by Eastern Ontario Leadership Council (EOLC) with the support of the Ontario Ministry of Labour, Training and Skills Development as at October 2, 2020 1 FOR MORE INFORMATION: www.eolc.info This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0). To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………………………….…….. 4 1. Overview: What We’ve Learned So Far (Key Observations)…………..……………… 4 2. How is economic resilience conceptualized (Definitions of Resilience)?.......... 5 3. The Study of Resilience is in Its Infancy…………………………………………………….….. 6 4. The Challenge of Measuring Resilience…………………………………………………..….... 6 5. Recurring Themes/ Factors of Resilience Identified in the Literature…………….. 7 1. Governance…………………………………………………………………………………………..… 8 2. Economic Structure……………………………………………………………………………….... 9 3. Innovation and Entrepreneurship………………………………………………………….. 10 4. Human Capital……………………………………………………………………………………….. 13 5. Additional Factors of Resilience Worth Observing………………………………….. 14 1. Digital Connectivity………………………………………………………………………….. 14 2. Social Capital and Social Cohesion……………………………………………….…… 15 6. Frameworks That Attempt to Measure and/or Assess Economic Resilience (Resilience Indices) ………………………………………………………………………..…………... 22 2. Appendices…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….