Program Notes | Rachmaninoff Live!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

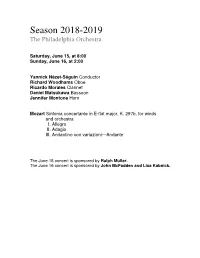

Season 2018-2019 the Philadelphia Orchestra

Season 2018-2019 The Philadelphia Orchestra Saturday, June 15, at 8:00 Sunday, June 16, at 2:00 Yannick Nézet-Séguin Conductor Richard Woodhams Oboe Ricardo Morales Clarinet Daniel Matsukawa Bassoon Jennifer Montone Horn Mozart Sinfonia concertante in E-flat major, K. 297b, for winds and orchestra I. Allegro II. Adagio III. Andantino con variazioni—Andante The June 15 concert is sponsored by Ralph Muller. The June 16 concert is sponsored by John McFadden and Lisa Kabnick. 24 The Philadelphia Orchestra Jessica Griffin The Philadelphia Orchestra Philadelphia is home and orchestra, and maximizes is one of the preeminent the Orchestra continues impact through Research. orchestras in the world, to discover new and The Orchestra’s award- renowned for its distinctive inventive ways to nurture winning Collaborative sound, desired for its its relationship with its Learning programs engage keen ability to capture the loyal patrons at its home over 50,000 students, hearts and imaginations of in the Kimmel Center, families, and community audiences, and admired for and also with those who members through programs a legacy of imagination and enjoy the Orchestra’s area such as PlayINs, side-by- innovation on and off the performances at the Mann sides, PopUP concerts, concert stage. The Orchestra Center, Penn’s Landing, free Neighborhood is inspiring the future and and other cultural, civic, Concerts, School Concerts, transforming its rich tradition and learning venues. The and residency work in of achievement, sustaining Orchestra maintains a Philadelphia and abroad. the highest level of artistic strong commitment to Through concerts, tours, quality, but also challenging— collaborations with cultural residencies, presentations, and exceeding—that level, and community organizations and recordings, the on a regional and national by creating powerful musical Orchestra is a global cultural level, all of which create experiences for audiences at ambassador for Philadelphia greater access and home and around the world. -

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

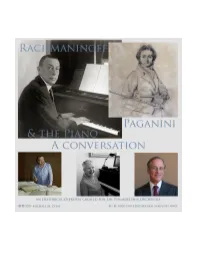

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation

Rachmaninoff, Paganini, & the Piano; a Conversation Tracks and clips 1. Rachmaninoff in Paris 16:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, 24 Caprices for Solo Violin, Op. 1, Michael Rabin, EMI 724356799820, recorded 9/5/1958. b. Sergey Rachmaninoff (SR), Rapsodie sur un theme de Paganini, Op. 43, SR, Leopold Stokowski, Philadelphia Orchestra (PO), BMG Classics 09026-61658, recorded 12/24/1934 (PR). c. Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin (FC), Twelve Études, Op. 25, Alfred Cortot, Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft (DGG) 456751, recorded 7/1935. d. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, SR, Eugene Ormandy (EO), PO, Naxos 8.110601, recorded 12/4/1939.* e. Carl Maria von Weber, Rondo Brillante in E♭, J. 252, Julian Jabobson, Meridian CDE 84251, released 1993.† f. FC, Twelve Études, Op. 25, Ruth Slenczynska (RS), Musical Heritage Society MHS 3798, released 1978. g. SR, Preludes, Op. 32, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. h. Georges Enesco, Cello & Piano Sonata, Op. 26 No. 2, Alexandre Dmitriev, Alexandre Paley, Saphir Productions LVC1170, released 10/29/2012.† i. Claude Deubssy, Children’s Corner Suite, L. 113, Walter Gieseking, Dante 167, recorded 1937. j. Ibid., but SR, Victor B-24193, recorded 4/2/1921, TvJ35-zZa-I. ‡ k. SR, Piano Concerto No. 3 in d, Op. 30, Walter Gieseking, John Barbirolli, Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, Music & Arts MACD 1095, recorded 2/1939.† l. SR, Preludes, Op. 23, RS, Ivory Classics 64405-70902, recorded 4/8/1984. 2. Rachmaninoff & Paganini 6:08 a. Niccolò Paganini, op. cit. b. PR. c. Arcangelo Corelli, Violin Sonata in d, Op. 5 No. 12, Pavlo Beznosiuk, Linn CKD 412, recorded 1/11/2012.♢ d. -

(The Bells), Op. 35 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) Written: 1913 Movements: Four Style: Romantic Duration: 35 Minutes

Kolokola (The Bells), Op. 35 Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873–1943) Written: 1913 Movements: Four Style: Romantic Duration: 35 minutes Sometimes an anonymous tip pays off. Sergei Rachmaninoff’s friend Mikhail Buknik had a student who seemed particularly excited about something. She had read a Russian translation of Edgar Allen Poe’s The Bells and felt that it simply had to be set to music. Buknik recounted what happened next: She wrote anonymously to her idol [Rachmaninoff], suggesting that he read the poem and compose it as music. summer passed, and then in the autumn she came back to Moscow for her studies. What had now happened was that she read a newspaper item that Rachmaninoff had composed an outstanding choral symphony based on Poe's Bells and it was soon to be performed. Danilova was mad with joy. Edgar Allen Poe (1809–1849) wrote The Bells a year before he died. It is in four verses, each one highly onomatopoeic (a word sounds like what it means). In it Poe takes the reader on a journey from “the nimbleness of youth to the pain of age.” The Russian poet Konstantin Dmitriyevich Balmont (1867–1942) translated Poe’s The Bells and inserted lines here and there to reinforce his own interpretation. Rachmaninoff conceived of The Bells as a sort of four-movement “choral-symphony.” The first movement evokes the sound of silver bells on a sleigh, a symbol of birth and youth. Even in this joyous movement, Balmont’s verse has an ominous cloud: “Births and lives beyond all number/Waits a universal slumber—deep and sweet past all compare.” The golden bells in the slow second movement are about marriage. -

PROGRAM NOTES Witold Lutosławski Concerto for Orchestra

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Witold Lutosławski Born January 25, 1913, Warsaw, Poland. Died February 7, 1994, Warsaw, Poland. Concerto for Orchestra Lutosławski began this work in 1950 and completed it in 1954. The first performance was given on November 26, 1954, in Warsaw. The score calls for three flutes and two piccolos, three oboes and english horn, three clarinets and bass clarinet, three bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, four trumpets, four trombones and tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, two harps, piano, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-eight minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra's first subscription concert performances of Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra were given at Orchestra Hall on February 6, 7, and 8, 1964, with Paul Kletzki conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performance was given November 7, 8, and 9, 2002, with Christoph von Dohnányi conducting. The Orchestra has performed this concerto at the Ravinia Festival only once, on June 28, 1970, with Seiji Ozawa conducting. For the record The Orchestra recorded Lutosławski's Concerto for Orchestra in 1970 under Seiji Ozawa for Angel, and in 1992 under Daniel Barenboim for Erato. To most musicians today, as to Witold Lutosławski in 1954, the title “concerto for orchestra” suggests Béla Bartók's landmark 1943 score of that name. Bartók's is the most celebrated, but it's neither the first nor the last work with this title. Paul Hindemith, Walter Piston, and Zoltán Kodály all wrote concertos for orchestra before Bartók, and Witold Lutosławski, Michael Tippett, Elliott Carter, and Shulamit Ran are among those who have done so after his famous example. -

Rachmaninoff's Rhapsody on a Theme By

RACHMANINOFF’S RHAPSODY ON A THEME BY PAGANINI, OP. 43: ANALYSIS AND DISCOURSE Heejung Kang, B.A., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2004 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor and Program Coordinator Stephen Slottow, Minor Professor Josef Banowetz, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Interim Chair of Piano Jessie Eschbach, Chair of Keyboard Studies James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Sandra L. Terrill, Interim Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Kang, Heejung, Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43: Analysis and Discourse. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2004, 169 pp., 40 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 39 titles. This dissertation on Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini, Op.43 is divided into four parts: 1) historical background and the state of the sources, 2) analysis, 3) semantic issues related to analysis (discourse), and 4) performance and analysis. The analytical study, which constitutes the main body of this research, demonstrates how Rachmaninoff organically produces the variations in relation to the theme, designs the large-scale tonal and formal organization, and unifies the theme and variations as a whole. The selected analytical approach is linear in orientation - that is, Schenkerian. In the course of the analysis, close attention is paid to motivic detail; the analytical chapter carefully examines how the tonal structure and motivic elements in the theme are transformed, repeated, concealed, and expanded throughout the variations. As documented by a study of the manuscripts, the analysis also facilitates insight into the genesis and structure of the Rhapsody. -

Pastiche for Piano on Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music

Pastiche For Piano On Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji Op 6 Sheet Music Download pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music pdf now available in our library. We give you 4 pages partial preview of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 sheet music that you can try for free. This music notes has been read 2619 times and last read at 2021-09-28 10:12:03. In order to continue read the entire sheet music of pastiche for piano on kaikhosru shapurji sorabji op 6 you need to signup, download music sheet notes in pdf format also available for offline reading. Instrument: Piano Method, Piano Solo Ensemble: Mixed Level: Advanced [ READ SHEET MUSIC ] Other Sheet Music Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 Opus Calidoscopium In Memory Of Sorabji Op 2 sheet music has been read 3180 times. Opus calidoscopium in memory of sorabji op 2 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-26 19:02:59. [ Read More ] Pastiche 2017 Pastiche 2017 sheet music has been read 2663 times. Pastiche 2017 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 6 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 02:51:33. [ Read More ] Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 Virtuoso Etude No 4 In Memory Of Sorabji Nocturne Op 1 sheet music has been read 2729 times. Virtuoso etude no 4 in memory of sorabji nocturne op 1 arrangement is for Advanced level. The music notes has 4 preview and last read at 2021-09-28 05:00:02. -

Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 As a Contribution to the Violist's

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2014 A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory Rafal Zyskowski Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Zyskowski, Rafal, "A tale of lovers : Chopin's Nocturne Op. 27, No. 2 as a contribution to the violist's repertory" (2014). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3366. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. A TALE OF LOVERS: CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE OP. 27, NO. 2 AS A CONTRIBUTION TO THE VIOLIST’S REPERTORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Rafal Zyskowski B.M., Louisiana State University, 2008 M.M., Indiana University, 2010 May 2014 ©2014 Rafal Zyskowski All rights reserved ii Dedicated to Ms. Dorothy Harman, my best friend ever iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As always in life, the final outcome of our work results from a contribution that was made in one way or another by a great number of people. Thus, I want to express my gratitude to at least some of them. -

Elizabeth Joy Roe, Piano

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts STEPHEN A. SCHWARZMAN , Chairman MICHAEL M. KAISER , President TERRACE THEATER Saturday Evening, October 31, 2009, at 7:30 presents Elizabeth Joy Roe, Piano BACH/SILOTI Prelude in B minor CORIGLIANO Etude Fantasy (1976) For the Left Hand Alone Legato Fifths to Thirds Ornaments Melody CHOPIN Nocturne in C-sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 1 WAGNER/LISZT Isoldens Liebestod RAVEL La Valse Intermission MUSSORGSKY Pictures at an Exhibition Promenade The Gnome Promenade The Old Castle Promenade Tuileries The Ox-Cart Promenade Ballet of the Unhatched Chicks Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle Promenade The Market at Limoges (The Great News) The Catacombs With the Dead in a Dead Language Baba-Yaga’s Hut The Great Gate of Kiev Elizabeth Joy Roe is a Steinway Artist Patrons are requested to turn off pagers, cellular phones, and signal watches during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. Notes on the Program By Elizabeth Joy Roe Prelude in B minor Liszt and Debussy. Yet Corigliano’s etudes JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH ( 1685 –1750) are distinctive in their effective synthesis of trans. ALEXANDER SILOTI (1863 –1945) stark dissonance and an expressive landscape grounded in Romanticism. Alexander Siloti, the legendary Russian pianist, The interval of a second—and its inversion composer, conductor, teacher, and impresario, and expansion to sevenths and ninths—is the was the bearer of an impressive musical lineage. connective thread between the etudes; its per - He studied with Franz Liszt and was the cousin mutations supply the foundation for the work’s and mentor of Sergei Rachmaninoff. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 66,1946-1947

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephone, Commonwealth 1492 SIXTY-SIXTH SEASON, 1946-1947 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor Richard Burgin, Associate Conductor with historical and descriptive notes by John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1946, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, ltlC. The TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Henry B. Cabot .* President Henry B. Sawyer . Vice-President Richard C. Paine . Treasurer Philip R. Allen M. A. De Wolfe Howe Nicholas John Brown Jacob J. Kaplan Alvan T. Fuller Roger I. Lee Jerome D. Greene Bentley W. Warren N. Penrose Hallowell Raymond S. Wilkins Francis W. Hatch Oliver Wolcott George E. Judd, Manager [577] © © © HOW YOU CAN HAVE A © © Financial "Watch-Dog" © © B © © © B B Webster defines a watch- dog as one kept to watch © and guard." With a Securities Custody Account at © the Shawmut Bank, you in effect put a financial watch- © dog on guard over your investments. And you are re- © lieved of all the bothersome details connected with © © owning stocks or bonds. An Investment Management © Account provides all the services of a Securities Cus- © tody Account and, in addition, you obtain the benefit B the judgment of B of composite investment our Trust B Committee. © Why not get all the facts now, without obligation? © © Call, write or telephone for our booklet: How to be © More Efficient in Handling Your Investments." © © •JeKdimiM \Jwu6t Q/sefi€VKtment © © © The D^ational © © Bank © Shawmut © 40 Water Street^ Boston © Member Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation © Capital $ 10,000,000 Surplus $20,000,000 © © "Outstanding Strength" for no Tears © © © I 578 ] 5? SYMPHONIANA LAURELS IN THE WEST At the beginning of this month the Boston Symphony Orchestra gave ten concerts in cities west of New England. -

Alexander Glazunov

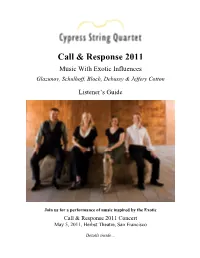

Call & Response 2011 Music With Exotic Influences Glazunov, Schulhoff, Bloch, Debussy & Jeffery Cotton Listener’s Guide Join us for a performance of music inspired by the Exotic Call & Response 2011 Concert May 5, 2011, Herbst Theatre, San Francisco Details inside… Call & Response 2011: Music with exotic influences Concert Thursday, May 5, 2011 Herbst Theatre at the San Francisco War Memorial 401 Van Ness Avenue at McAllister Street San Francisco, CA 7:15pm Pre-Performance Lecture by composer Jeffery Cotton 8:00pm Performance Buy tickets online at: www.cityboxoffice .com or by calling City Box Office: 415-392-4400 Page Contents 3 The Concept: evolution of music over time and across cultures 4 Jeffery Cotton 6 Alexander Glazunov 8 Erwin Schulhoff 10 Ernest Bloch 12 Claude Debussy 2 Call & Response: The Concept Have you ever wondered how composers, modern composers at that, come up with their ideas? How do composers and other artists create new work? Our Call & Response program was born out of the Cypress String Quartet’s commitment to sharing with you and your community this process in music and all kinds of other artwork. We present newly created music based on earlier composed pieces. Why “Call & Response”? We usually associate the term “call & response” with jazz and gospel music, the idea being that the musician plays a musical “call” to which another musician “responds,”—a way of creating a new sound relating in some way to the original. In this program, the “call” is that of Cypress String Quartet searching for connections across musical, historical, and social boundaries. -

Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-7-2018 12:30 PM Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse Renee MacKenzie The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nolan, Catherine The University of Western Ontario Sylvestre, Stéphan The University of Western Ontario Kinton, Leslie The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Music A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Musical Arts © Renee MacKenzie 2018 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation MacKenzie, Renee, "Rachmaninoff's Piano Works and Diasporic Identity 1890-1945: Compositional Revision and Discourse" (2018). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5572. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5572 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract This monograph examines the post-exile, multi-version works of Sergei Rachmaninoff with a view to unravelling the sophisticated web of meanings and values attached to them. Compositional revision is an important and complex aspect of creating musical meaning. Considering revision offers an important perspective on the construction and circulation of meanings and discourses attending Rachmaninoff’s music. While Rachmaninoff achieved international recognition during the 1890s as a distinctively Russian musician, I argue that Rachmaninoff’s return to certain compositions through revision played a crucial role in the creation of a narrative and set of tropes representing “Russian diaspora” following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.