Model Building N N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

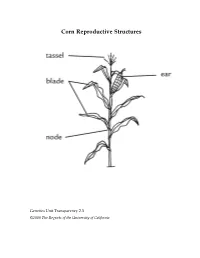

Corn Reproductive Structures

Corn Reproductive Structures Genetics Unit Transparency 2.3 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Creating a Punnett Square Genetics Unit Transparency 2.4 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Case Study Summary Sheet Case Study Type of Benefits Risks and concerns Remaining questions Genetic Modification Genetics Unit Transparency 4.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Class Data for Rice Breeding Simulation aromatic, non-aromatic, aromatic, non-aromatic ,flood-tolear nt flood-tolerant flood-intolerant flood-intolerant AAFF AAFf AaFF AaFf aaFF aaFf AAff Aaff aaff Group 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Genetics Unit Transparency 5.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Three Types of Cells Genetics Unit Transparency 6.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California DNA base percentages in a variety of organisms Source of A T G C DNA Human 31.0% 31.5% 19.1% 18.4% Mouse 29.1% 29.0% 21.1% 21.1% Frog 26.3% 26.4% 23.5% 23.8% Fruit fly 27.3% 27.6% 22.5% 22.5% Corn 25.6% 25.3% 24.5% 24.6% E. coli 24.6% 24.3% 25.5% 25.6% Genetics Unit Transparency 7.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl’s Experiment to Investigate DNA Replication First: Scientists James Watson and Francis Crick propose a method of semi-conservative replication in their paper on the structure of DNA. However, they have no data to support their hypothesis. Next: Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl use the procedure that follows to investigate DNA created by the process of DNA Replication. -

AP® Biology from Gene to Protein— a Historical Perspective

Professional Development AP® Biology From Gene to Protein— A Historical Perspective Curriculum Module The College Board The College Board is a not-for-profit membership association whose mission is to connect students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the association is composed of more than 5,700 schools, colleges, universities and other educational organizations. Each year, the College Board serves seven million students and their parents, 23,000 high schools, and 3,800 colleges through major programs and services in college readiness, college admission, guidance, assessment, financial aid and enrollment. Among its widely recognized programs are the SAT®, the PSAT/NMSQT®, the Advanced Placement Program® (AP®), SpringBoard and ACCUPLACER. The College Board is committed to the principles of excellence and equity, and that commitment is embodied in all of its programs, services, activities and concerns. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.com. The College Board acknowledges all the third party content that has been included in these materials and respects the Intellectual Property rights of others. If we have incorrectly attributed a source or overlooked a publisher, please contact us. Pages 7, 10, 21, 22, and 36: Figures 1–5 from Neil A. Campbell and Jane B. Reece, BIOLOGY, 7/E, © 2005. Reprinted by permission of Pearson Education Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. Page 56–60: Adapted from pGLO Bacterial Transformation Kit (catalog number 166- 0003EDU), Biotechnology Explorer™ instruction manual, Rev. E. Bio-Rad Laboratories, Life Science Education. 1-800-4-BIORAD (800-424-6723), www.explorer.bio-rad.com © 2010 The College Board. College Board, ACCUPLACER, Advanced Placement Program, AP, AP Central, Pre-AP, SpringBoard and the acorn logo are registered trademarks of the College Board. -

GENETICS Editorial Board Executive Editor

Mark Johnston, Editor-in-Chief University of Colorado-Denver Tracey DePellegrin Connelly, GENETICS Editorial Board Executive Editor CELLULAR GENETICS Thomas C. Kaufman GENOME AND SYSTEMS Wolfgang Stephan Orna Cohen-Fix Indiana University BIOLOGY University of Munich NIDDK, National Institutes of Health Kenneth J. Kemphues Jef Boeke Naoyuki Takahata Susan Dutcher Cornell University Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Graduate University for Washington University School Barbara J. Meyer Stanley Fields Advanced Studies of Medicine University of California, Berkeley University of Washington Marcy K. Uyenoyama JoAnne Engebrecht Trudi Schüpbach David Largaespada Duke University University of California, Davis Princeton University University of Minnesota Lindi M. Wahl University of Western Ontario David I. Greenstein Mariana F. Wolfner Jeffery F. Miller University of Minnesota Cornell University University of California, Los Angeles John Wakeley Harvard University Michael Nonet GENE EXPRESSION Peter J. Oefner Washington University School of Stanford University H. Allen Orr (Perspectives Editor) Karen Arndt University of Rochester Medicine University of Pittsburgh Norbert Perrimon Adam S. Wilkins (Perspectives Editor) Mark D. Rose Harvard Medical School James A. Birchler University of Cambridge Princeton University Piali Sengupta University of Missouri Patricia J. Pukkila (Genetics Education Linda Siracusa Brandeis University Charles Boone Editor) University of North Carolina Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Gary Stormo University of Toronto -

Investigating DNA Replication”

Sample student results, Student Sheet 8.1, “Investigating DNA Replication” p. 100 Science and Global Issues (SGI) Genetics: Feeding the World Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl’s Experiment to Investigate DNA Replication First: Scientists James Watson and Francis Crick propose a method of semi-conservative replication in their paper on the structure of DNA. However, they have no data to support their hypothesis. Next: Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl use the procedure that follows to investigate DNA created by the process of DNA Replication. Procedure 1. Place bacteria, Escherichia coli (E. coli) in a solution of “heavy” nitrogen. 2. Leave the E. coli in the “heavy” nitrogen solution until all DNA nucleotides, and all DNA strands, are made of “heavy” nitrogen. This is Generation Zero. 3. Isolate the DNA from the E. coli. 4. Place “heavy” DNA in a solution with the same density as DNA. Genetics Transparency 8.1a ©2008 The Regents of the University of California p. 107 Science and Global Issues (SGI) Genetics: Feeding the World 5. Run “heavy” DNA solution on a centrifuge. A band of “heavy” DNA forms in the test tube. 6. Transfer some of the E. coli with “heavy” DNA into a solution of “light” DNA. 7. Allow the E. coli to reproduce for 20 minutes (the reproduction time of E. coli). 8. Place E. coli in the solution and run the tube on a centrifuge. 9. Analyze the bands of DNA that form. 10. Repeat for 3 rounds of Replication. 11. Compare the bands that form for each round of replication. Genetics Transparency 8.1b ©2008 The Regents of the University of California p. -

CH 16 DNA Structure & Synthesis in 1953, James Watson and Francis

CH 16 DNA Structure & Synthesis In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick introduced an elegant double-helical model for the structure of deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA. DNA, the substance of inheritance, is the most celebrated molecule of our time. Hereditary information is encoded in DNA and reproduced in all cells of the body. This DNA program directs the development of biochemical, anatomical, physiological, and (to some extent) behavioral traits. Evidence that DNA is genetic material It was known that DNA is a polymer of nucleotides, each consisting of a nitrogenous base, a sugar, and a phosphate group. In 1950, Erwin Chargaff reported that DNA composition varies from one species to the next. This evidence of diversity made DNA a more credible candidate for the genetic material. Building Structural Model of DNA After DNA was accepted as the genetic material, the challenge was to determine how its structure accounts for its role in heredity. Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin were using a technique called X-ray crystallography to study molecular structure. Franklin produced a picture of the DNA molecule using this technique. Franklin’s X-ray crystallographic images of DNA enabled Watson to deduce that DNA was helical. The X-ray images also enabled Watson to deduce the width of the helix and the spacing of the nitrogenous bases. The pattern in the photo suggested that the DNA molecule was made up of two strands, forming a double helix. Base pairing to a template strand Since the two strands of DNA are complementary, each strand acts as a template for building a new strand in replication. -

Introduction to This Document the Eighth Day of CreationBy Horace

Introduction to this document The Eighth Day of Creation by Horace Freeland Judson is a narrative history of molecular biology. It tells the story of how scientists in the early-mid 20th century discovered the basic rules of life that we now call the Central Dogma. The book presents both an in-depth analysis of the foundational research and a look into the lives of the scientists involved. We used this book as the primary text for an advanced undergraduate seminar course at the University of Washington in Winter 2020. The course was rewarding for us and we felt our students got a unique perspective on scientific progress, so we wanted to share our syllabus (annotated with some reflections on the course) as inspiration for others to teach similar courses. We welcome any questions, comments, or contributions. If you decide to teach a course with Eighth Day please let us know how it goes! Table of Contents Syllabus 2 Recommendations for future instructors 6 Example writing prompts 8 Additional relevant media 10 Reading assignments for The Eighth Day of Creation 1st edition 12 Reading assignments for The Eighth Day of Creation Commemorative edition 16 Condensed reading list (select discoveries and personal accounts) 20 1 Honors 396A/Genome 490 Scientific Revolution and Molecular Biology: ‘The Eighth Day of Creation’ Instructors Elizabeth Morton, [email protected] Bryce Taylor, [email protected] Course overview The founding of molecular biology was a synthesis of ideas from physics, biology, and chemistry. The efforts of its interdisciplinary founders laid out a vision of life as composed of molecular systems orchestrated by a progression of information from DNA to RNA to protein – what we now call the central dogma. -

GENETICS Editorial Board Executive Editor

Mark Johnston, Editor-in-Chief University of Colorado-Denver Tracey DePellegrin Connelly, GENETICS Editorial Board Executive Editor CELLULAR GENETICS Lawrence G. Harshman GENOME AND SYSTEMS Hamish Spencer Orna Cohen-Fix University of Nebraska, Lincoln BIOLOGY University of Otago NIDDK, National Institutes of Health Thomas C. Kaufman Jef Boeke Naoyuki Takahata Susan Dutcher Indiana University Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Graduate University for Washington University School Kenneth J. Kemphues Stanley Fields Advanced Studies of Medicine Cornell University University of Washington Marcy K. Uyenoyama Duke University JoAnne Engebrecht Barbara J. Meyer David Largaespada University of California, Davis University of California, Berkeley University of Minnesota Lindi M. Wahl University of Western Ontario David I. Greenstein Trudi Schüpbach Jeffery F. Miller University of Minnesota Princeton University University of California, Los Angeles John Wakeley Harvard University Michael Nonet Mariana F. Wolfner Peter J. Oefner Washington University School Cornell University Stanford University H. Allen Orr (Perspectives Editor) of Medicine University of Rochester Norbert Perrimon GENE EXPRESSION Adam S. Wilkins (Perspectives Editor) Mark D. Rose Harvard Medical School Princeton University Karen Arndt University of Cambridge Piali Sengupta University of Pittsburgh Patricia J. Pukkila (Genetics Education Linda Siracusa Brandeis University Jefferson Medical College of Thomas James A. Birchler Editor) University of North Carolina Gary Stormo Jefferson -

Population Dynamics of a Lac- Strain of Escherichia Coli During Selection for Lactose Utilization

Copyright 0 1994 by the Genetics Society of America Population Dynamics of a Lac- Strain of Escherichia coli During Selection for Lactose Utilization Patricia L. Foster Department of Environmental Health, Boston University School of Public Health, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts 021 18 Manuscript received February 25, 1994 Accepted for publication June 18, 1994 ABSTRACT During selectionfor lactose utilization,Lac' revertants of FC40, a Lac- strainof Escherichia coli, appear at a high rate. Yet, no Lac' revertants appear in the absence of lactose, or in its presenceif the cells have another, unfulfilled requirement for growth. This study investigatesmore fully the population dynamics of FC40 when incubated in the absence of a carbon source or when undergoing selection for lactose utilization. In the absence of a carbon source, the viable cell numbers do not change over 6 days. When incubated in liquid lactose medium, Lac- cells do not undergo any measurable increase innumbers or in turbidity for at least 2 days. When FC40 is plated on lactose minimum medium in the presence of scavenger cells,the upper limit to the amount of growth of Lac- cells during 5 days is one doubling, and there is no evidence for turnover (i.e., a balance between growthand death).The presence of a minority population that could form microcolonies was not detected. The implications of these results, plus the fact that the appearance of Lac' revertants during lactose selection is nearly constant with time, are discussed in reference to several models that have been postulated to account for adaptive mutations. T is generally believed that all spontaneous mutations had another, unfulfilled growth requirement (CAIRNS I arise at random as a result of errors made during and FOSTER1991). -

The Discovery of DNA Structure and Replication by Kevin M

NATIONAL CENTER FOR CASE STUDY TEACHING IN SCIENCE Putting the Pieces Together: The Discovery of DNA Structure and Replication by Kevin M. Bonney Liberal Studies, Faculty of Arts and Sciences New York University, New York, NY Part I – Setting the Stage In the autumn of 1952, while the weather in London, England, was cooling down, the race to discover the structure of DNA was heating up inside two rival laboratories: the Cavendish Lab at Cambridge University and the laboratory of J.T. Randall at nearby King’s College. DNA had recently been identifed as the hereditary material that organisms use to transmit genetic traits from one generation to another. T is f nding is largely attributed to the work of two groups of American scientists, Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, and Macyln McCarty of the Rockefeller Institute, and Alfred Hershey and Martha Chase of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, though many important experiments conducted by other scientists were crucial to developing this understanding. Te next great challenge was to identify the structure of DNA so that we could understand how the information contained in DNA is copied and passed from cell to cell, and how that information is translated into the instructions for building the proteins necessary for life. Te groundbreaking research of the Cavendish and Randall laboratories describing the structure of DNA was published in a series of papers in the journal Nature on April 25, 1953 [Wilkins et al., 1953; Franklin et al., 1953]. Tese would become known as some of the most important scientifc papers ever published, as well as a symbol of great controversy involving allegations of misogyny and ethics violations among scientists who would go on to win a Nobel Prize. -

In-Depth Film Guide

Short Film The Double Helix Educator Materials IN-DEPTH FILM GUIDE DESCRIPTION The film The Double Helix describes the trail of evidence James Watson and Francis Crick followed to discover the double-helical structure of DNA. Their model’s beautiful and simple structure immediately revealed how genetic information is stored and passed from one generation to the next. KEY CONCEPTS A. DNA is a polymer of nucleotide monomers, each consisting of a phosphate, a deoxyribose sugar, and one of four nitrogenous bases: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), or cytosine (C). B. The relative amounts of A, T, G, and C bases vary from one species to another; however, in the DNA of any cell from organisms within a single species, the amount of A is equal to the amount of T and the amount of G is equal to the amount of C. This finding can be explained by the fact that in the DNA double helix, A pairs with T and G with C. C. Even before the structure of DNA was solved, studies indicated that the genetic material must be able to store information; be faithfully replicated and be passed on from generation to generation; and allow for changes, and thus evolution, to occur. The structure of the double helix immediately showed that DNA had these properties. D. Scientists use different techniques to measure things that are too large or too small to see. The structure of DNA was determined by combining mathematical interpretations of x-ray crystallography data and chemical data. E. Scientists build models based on what they know from previous research to derive testable hypotheses. -

The Double Helix Film Activity Educator Materials

The Double Helix Film Activity Educator Materials OVERVIEW This activity explores the concepts and research presented in the short film The Double Helix, which tells the story of the discovery of the molecular structure of DNA. Scientists collected and interpreted key evidence to determine that DNA molecules take the shape of a twisted ladder, a double helix. The film presents the challenges, false starts, and eventual success of their chase, culminating in the classic 1953 publication in Nature on the structure of DNA. Additional information related to pedagogy and implementation can be found on this resource’s webpage, including suggested audience, estimated time, and curriculum connections. KEY CONCEPTS • DNA is a polymer of nucleotide monomers, each consisting of a phosphate, a deoxyribose sugar, and one of four nitrogenous bases: adenine (A), thymine (T), guanine (G), or cytosine (C). A pairs with T and G with C. • DNA’s structure allows it to store information, be consistently replicated between generations, and facilitate certain changes (and thus evolution). • Scientists can use various techniques, such as x-ray crystallography and chemical analyses, to measure things that are too large or too small to see. • Scientists can use models to generate and test hypotheses. They often revise their models based on additional data. • The process of scientific discovery involves brainstorming and evaluating ideas, making mistakes, rethinking ideas based on evidence, and communicating with others. STUDENT LEARNING TARGETS • Explain how evidence collected by the scientific community allowed Watson and Crick to build a model of DNA. • Describe some of the key structural features of DNA and their relationship to DNA’s function. -

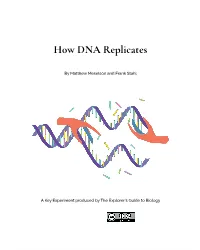

How DNA Replicates

How DNA Replicates By Matthew Meselson and Frank Stahl A Key Experiment produced by The Explorer’s Guide to Biology 2 Th e Explorer’s Guide to Biology https://explorebiology.org/ How DNA Replicates Matthew Meselson, Harvard University, and Franklin W. Stahl, University of Oregon Matthew Meselson Matthew Meselson had a passion for physics and chemistry throughout his early life, often conducting science experiments in his family’s garage. At the age of 16, he enrolled at the University of Chicago, beginning an academic career that led to doctoral studie s at the California Institute of Technology under Linus Pauling. In addition to his widely known work demonstrating semi-conservative replication of DNA with Frank Stahl, Meselson has made many key discoveries in the molecular biology. He is also known for his work in limiting the proliferation of chemical and biolog- ical weapons. Meselson is a member of the National Academy of Science and a recipient of the Lasker Award. He continues to serve as a member of the faculty at Harvard University, where he has taught and conducted research since 1960. Franklin Stahl Following a sheltered life in a Boston suburb (Needham), Frank stum- bled his way through college (Harvard, 1951) before fl eeing to a graduate school in biology (U Rochester) to avoid the military draft. While in the graduate school, Frank took a course taught by A. H. (Gus) Doermann, and, for the fi rst time in his life, he had a goal. With Gus, he studied genetic recombination in phage. To meet a departmental requirement, Frank took a summer course at Woods Hole, where he met Matt Meselson and began the work described in this Key Experiment.