By Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl [1]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

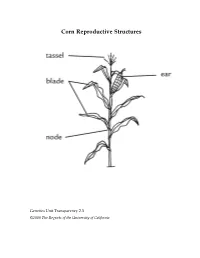

Corn Reproductive Structures

Corn Reproductive Structures Genetics Unit Transparency 2.3 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Creating a Punnett Square Genetics Unit Transparency 2.4 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Case Study Summary Sheet Case Study Type of Benefits Risks and concerns Remaining questions Genetic Modification Genetics Unit Transparency 4.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Class Data for Rice Breeding Simulation aromatic, non-aromatic, aromatic, non-aromatic ,flood-tolear nt flood-tolerant flood-intolerant flood-intolerant AAFF AAFf AaFF AaFf aaFF aaFf AAff Aaff aaff Group 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Genetics Unit Transparency 5.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Three Types of Cells Genetics Unit Transparency 6.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California DNA base percentages in a variety of organisms Source of A T G C DNA Human 31.0% 31.5% 19.1% 18.4% Mouse 29.1% 29.0% 21.1% 21.1% Frog 26.3% 26.4% 23.5% 23.8% Fruit fly 27.3% 27.6% 22.5% 22.5% Corn 25.6% 25.3% 24.5% 24.6% E. coli 24.6% 24.3% 25.5% 25.6% Genetics Unit Transparency 7.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl’s Experiment to Investigate DNA Replication First: Scientists James Watson and Francis Crick propose a method of semi-conservative replication in their paper on the structure of DNA. However, they have no data to support their hypothesis. Next: Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl use the procedure that follows to investigate DNA created by the process of DNA Replication. -

JESSICA L. MARK WELCH Assistant Research Scientist Josephine Bay

JESSICA L. MARK WELCH Assistant Research Scientist Josephine Bay Paul Center, Marine Biological Laboratory 7 MBL Street, Woods Hole, MA 02543 Telephone (508) 289-7180, e-mail [email protected] EDUCATION: B.A. magna cum laude, Harvard and Radcliffe Colleges, Biology, 1989 Graduate work, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany, Chemistry and Biology, 1990-1992 Advisor: Walter Sudhaus Ph.D., Harvard University Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Biology, 2001 Advisor: Matthew Meselson. Dissertation topic: Cytological Evidence for the Absence of Meiosis in Bdelloid Rotifers. Postdoctoral training, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Molecular Biology 2001-2006 part-time 2006-2009 full-time Advisors: Matthew Meselson and Gary Borisy PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS: 1989 – 1990 Research Assistant, Environmental Law Institute, Washington, DC 2009 – present Assistant Research Scientist, Josephine Bay Paul Center for Comparative Molecular Biology and Evolution, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA. PUBLICATIONS: Valm, Alex M., Jessica L. Mark Welch, and Gary G. Borisy (2012). CLASI-FISH: Principles of Combinatorial Labeling and Spectral Imaging. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 2012 Apr 21 (Epub ahead of print). PMCID: PMC3407316. Sukenik, Assaf, Ruth N. Kaplan-Levy, Jessica Mark Welch, and Anton Post (2011). Massive multiplication of genome and ribosomes in dormant cells (akinetes) of Aphanizomenon ovalisporum (Cyanobacteria). The ISME Journal 2011.128 (epub ahead of print, October 6, 2011). Valm, Alex M., Jessica L. Mark Welch, Christopher W. Rieken, Yuko Hasegawa, Mitchell L. Sogin, Rudolf Oldenbourg, Floyd E. Dewhirst, and Gary G. Borisy (2011). Systems-level analysis of microbial community organization through combinatorial labeling and spectral imaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA) 108: 4152-4157. -

Matthew Meselson and Federal Policy on Chemical and Biological Warfare

142 The People's Science Advisora-Can Outsiders Be Ef(ectivef . D .__ 30 1969 p 14· January 4, 1970, p. 29; February 2, 53. New York T1me1, ecem..... • ' • ' CHAPTER 11. 1970,p.27. 35 54 New York Timei,June 18, 1970, p. • 0 6 9 55: Time, April 12, 1971, P· 45;New YorkNT::J~~~~! i?e,i!~s ·in· Pepper Fields," 56. Robert Gillette, "DDT: lts Days ue u er ' Seien« 176 (1972): 1313. 0 72-1548 etc. (6 suits). December 18, 197~. " Matthew Meselson and the 51. EDF et. al v. EPA etc., D.C. Clorar.. p. Result of lnsect Resistance, New Chemu:als, 58. "Decreasing Use of Organoch mes as 9 Chemical and Engineering N;,wsk, AT~~ No• ~:~~·{1\911, Section IV, P· 13. 59. Quoted in the New • or rme-, • United States Policy on 60. Jbid. 61. Jbid. ered •• 1314 62. Gillette, "DDT: lts Days Are Numb ••AiXrin and Dieldrin," Environment, October 63. See, for example, tbarles F. Wurstel, Chemical and 1971, p. 33. • . .cals re ·stered ror use in the United States. 64. In 1969 there were 900 pestic:'dal c~ on';.e1ticide111nd Their Relationship to See, c.g., thc Report of the SeaetflTY 'Com n Biological Warfare Envi1onmento1Health, p. 46. Mattbew Meselson is a sligbt, soft-spoken professor of biochemistry at Harvard wbo often seems to be occupying the calm at the center of a burricane of activity. The scene wbicb greeted one of the authors on an aftemoon visit to bis laboratory during the spring of 1973 was typical: Meselson's graduate students bad congregated for wine, cheese, discussion, and laughter in a room next to bis office. -

AP® Biology from Gene to Protein— a Historical Perspective

Professional Development AP® Biology From Gene to Protein— A Historical Perspective Curriculum Module The College Board The College Board is a not-for-profit membership association whose mission is to connect students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the association is composed of more than 5,700 schools, colleges, universities and other educational organizations. Each year, the College Board serves seven million students and their parents, 23,000 high schools, and 3,800 colleges through major programs and services in college readiness, college admission, guidance, assessment, financial aid and enrollment. Among its widely recognized programs are the SAT®, the PSAT/NMSQT®, the Advanced Placement Program® (AP®), SpringBoard and ACCUPLACER. The College Board is committed to the principles of excellence and equity, and that commitment is embodied in all of its programs, services, activities and concerns. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.com. The College Board acknowledges all the third party content that has been included in these materials and respects the Intellectual Property rights of others. If we have incorrectly attributed a source or overlooked a publisher, please contact us. Pages 7, 10, 21, 22, and 36: Figures 1–5 from Neil A. Campbell and Jane B. Reece, BIOLOGY, 7/E, © 2005. Reprinted by permission of Pearson Education Inc., Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. Page 56–60: Adapted from pGLO Bacterial Transformation Kit (catalog number 166- 0003EDU), Biotechnology Explorer™ instruction manual, Rev. E. Bio-Rad Laboratories, Life Science Education. 1-800-4-BIORAD (800-424-6723), www.explorer.bio-rad.com © 2010 The College Board. College Board, ACCUPLACER, Advanced Placement Program, AP, AP Central, Pre-AP, SpringBoard and the acorn logo are registered trademarks of the College Board. -

Allele Sharing and Evidence for Sexuality in a Mitochondrial Clade of Bdelloid Rotifers

HIGHLIGHTED ARTICLE GENETICS | INVESTIGATION Allele Sharing and Evidence for Sexuality in a Mitochondrial Clade of Bdelloid Rotifers Ana Signorovitch,* Jae Hur,*,† Eugene Gladyshev,* and Matthew Meselson*,‡,1 *Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, †Department of Biology, Harvey Mudd College, Claremont, California 91711, and ‡Josephine Bay Paul Center, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Massachusetts 02543 ORCID IDs: 0000-0003-1446-2305 (J.H.); 0000-0002-4074-4966 (E.G.); 0000-0002-9827-2682 (M.M.) ABSTRACT Rotifers of Class Bdelloidea are common freshwater invertebrates of ancient origin whose apparent asexuality has posed a challenge to the view that sexual reproduction is essential for long-term evolutionary success in eukaryotes and to hypotheses for the advantage of sex. The possibility nevertheless exists that bdelloids reproduce sexually under unknown or inadequately investigated conditions. Although certain methods of population genetics offer definitive means for detecting infrequent or atypical sex, they have not previously been applied to bdelloid rotifers. We conducted such a test with bdelloids belonging to a mitochondrial clade of Macrotrachela quadricornifera. This revealed a striking pattern of allele sharing consistent with sexual reproduction and with meiosis of an atypical sort, in which segregation occurs without requiring homologous chromosome pairs. KEYWORDS clonal erosion; cyclic parthenogenesis; meiosis; monogonont; Oenothera DELLOID rotifers are minute freshwater invertebrates com- families and hundreds of morphospecies, their ancient origin is Bmonly found in lakes, streams, and ponds and in ephem- indicated by the considerable synonymous sequence divergence erally aquatic environments such as rock pools and the water between families and by the finding of bdelloid remains in 35- to films on moss and lichens where they are able to survive because 40-million year old amber (Mark Welch et al. -

![Matthew Stanley Meselson (1930– ) [1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2149/matthew-stanley-meselson-1930-1-1732149.webp)

Matthew Stanley Meselson (1930– ) [1]

Published on The Embryo Project Encyclopedia (https://embryo.asu.edu) Matthew Stanley Meselson (1930– ) [1] By: Hernandez, Victoria Keywords: semiconservative replication [2] Matthew Stanley Meselson conducted DNA and RNA research in the US during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. He also influenced US policy regarding the use of chemical and biological weapons. Meselson and his colleague Franklin Stahl demonstrated that DNA replication is semi-conservative. Semi-conservative replication means that every newly replicated DNA double helix, which consists of two individual DNA strands wound together, contains one strand that was conserved from a parent double helix and that served as a template for the other strand. Meselson's work enabled researchers to better explain and control cellular development by showing how DNA are copied when a cell divides and interpreted when a cell makes proteins. Meselson was born in Denver, Colorado, to Ann and Hyman Meselson on 24 May 1930. At the age of two, Meselson and his family moved to Los Angeles, California, where he grew up as an only child. According to Meselson, even as a boy he wanted to be a scientist. Meselson built his own chemistry lab in the garage of his home using a chemistry set given to him by his uncle Morris. According to Frederic Lawrence Holmes, a historian of science, Meselson said that his interest in chemistry continued to develop in high school because his chemistry teacher, Elizabeth Butcher, challenged him. Meselson also claimed that he was fascinated by the question of how life originated. He said that he wondered whether electricity was the source of life, and he imagined himself as an electrochemist discovering the means to create life. -

Why Is DNA Double Stranded? the Discovery of DNA Excision Repair Mechanisms

| PERSPECTIVES Why Is DNA Double Stranded? The Discovery of DNA Excision Repair Mechanisms Bernard S. Strauss1 Department of Molecular Genetics and Cell Biology, The University of Chicago, Illinois 60637 ORCID ID: 0000-0001-7548-6461 (B.S.S.) ABSTRACT The persistence of hereditary traits over many generations testifies to the stability of the genetic material. Although the Watson–Crick structure for DNA provided a simple and elegant mechanism for replication, some elementary calculations implied that mistakes due to tautomeric shifts would introduce too many errors to permit this stability. It seemed evident that some additional mechanism(s) to correct such errors must be required. This essay traces the early development of our understanding of such mech- anisms. Their key feature is the cutting out of a section of the strand of DNA in which the errors or damage resided, and its replacement by a localized synthesis using the undamaged strand as a template. To the surprise of some of the founders of molecular biology, this understanding derives in large part from studies in radiation biology, a field then considered by many to be irrelevant to studies of gene structure and function. Furthermore, genetic studies suggesting mechanisms of mismatch correction were ignored for almost a decade by biochemists unacquainted or uneasy with the power of such analysis. The collective body of results shows that the double-stranded structure of DNA is critical not only for replication but also as a scaffold for the correction of errors and the removal of damage to DNA. As additional discoveries were made, it became clear that the mechanisms for the repair of damage were involved not only in maintaining the stability of the genetic material but also in a variety of biological phenomena for increasing diversity, from genetic recombination to the immune response. -

GENETICS Editorial Board Executive Editor

Mark Johnston, Editor-in-Chief University of Colorado-Denver Tracey DePellegrin Connelly, GENETICS Editorial Board Executive Editor CELLULAR GENETICS Thomas C. Kaufman GENOME AND SYSTEMS Wolfgang Stephan Orna Cohen-Fix Indiana University BIOLOGY University of Munich NIDDK, National Institutes of Health Kenneth J. Kemphues Jef Boeke Naoyuki Takahata Susan Dutcher Cornell University Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Graduate University for Washington University School Barbara J. Meyer Stanley Fields Advanced Studies of Medicine University of California, Berkeley University of Washington Marcy K. Uyenoyama JoAnne Engebrecht Trudi Schüpbach David Largaespada Duke University University of California, Davis Princeton University University of Minnesota Lindi M. Wahl University of Western Ontario David I. Greenstein Mariana F. Wolfner Jeffery F. Miller University of Minnesota Cornell University University of California, Los Angeles John Wakeley Harvard University Michael Nonet GENE EXPRESSION Peter J. Oefner Washington University School of Stanford University H. Allen Orr (Perspectives Editor) Karen Arndt University of Rochester Medicine University of Pittsburgh Norbert Perrimon Adam S. Wilkins (Perspectives Editor) Mark D. Rose Harvard Medical School James A. Birchler University of Cambridge Princeton University Piali Sengupta University of Missouri Patricia J. Pukkila (Genetics Education Linda Siracusa Brandeis University Charles Boone Editor) University of North Carolina Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Gary Stormo University of Toronto -

Meselson, Stahl, and the Replication of DNA: a History of "The Most Beautiful

© 2002 by The International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology BIOCHEMISTRY AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY EDUCATION Printed in U.S.A. Vol. 30, No. 6, pp. 431–435, 2002 Book Reviews Enzyme Kinetics: Principles and Methods (1st English an effort to reconstruct the history of “The Most Beautiful Ed.; translation of 3rd German Ed.) Experiment in Biology” (this quote is attributed to John Bisswanger, H. (Bubenheim, L., translator); Wiley-VCH, Cairns as reported in Horace Judson’s Eighth Day of Cre- Weinheim, 2002, 255 pp. ϩ CD-ROM, ISBN 3-527- ation). The trio examined extant records, notes from 30343-X, $95.00. Meselson’s workbook, centrifuge logs, and photographs containing the results of centrifugation experiments (many This book on enzyme kinetics takes what is, to my of which are reproduced in the book). Holmes also exam- knowledge, a unique approach to the discipline. The first ined periodic reports written for the California Institute of part is a thorough discussion of substrate binding, inde- Technology (Caltech) and the National Association for In- pendent of the enzymatic reaction, and deals with the fantile Paralysis; these were generally the work of Stahl. phenomena of multiple binding sites, both independent Other sources include discussions with Gunther Stent, and interacting. There is detailed graphical representation John Cairns, James D. Watson, and Howard Schachman. of the various equations showing what would be expected As an historian of science, Holmes sought the help of for weak and strong interactions and cooperativity, both these experts to learn the scientific principles involved. His positive and negative. explanations are thorough, and his sources are cited in The second part is the most traditional with detailed notes that accompany each chapter. -

The Centenary of Janssens's Chiasmatype Theory

PERSPECTIVES The Centenary of Janssens’s Chiasmatype Theory Romain Koszul,*,†,1 Matthew Meselson,‡ Karine Van Doninck,§ Jean Vandenhaute,** and Denise Zickler††,1 *Institut Pasteur, Group Spatial Regulation of Genomes, Department of Genomes and Genetics, F-75015 Paris, France, †2 Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Unité Mixte de Recherche (UMR) 3525, F-75015 Paris, France, ‡Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA 02138, §Université de Namur, Facultés universitaires Notre-Dame de la Paix (FUNDP), Unité de Recherche en Biologie des Organismes, B5000 Namur, Belgium, **Université de Namur, FUNDP, Unité de Recherche en Biologie Moléculaire et Département Sciences, Philosophies et Sociétés, B5000 Namur, Belgium, and ††Institut de Génétique et Microbiologie, UMR 8621, Université Paris-Sud, 91405 Orsay, France ABSTRACT The segregation and random assortment of characters observed by Mendel have their basis in the behavior of chromosomes in meiosis. But showing this actually to be the case requires a correct understanding of the meiotic behavior of chromosomes. This was achieved only gradually, over several decades, with much dispute and confusion along the way. One crucial step in the understanding of meiosis was provided in 1909 by Frans Alfons Janssens who published in La Cellule an article entitled “La théorie de la Chiasmatypie. Nouvelle interprétation des cinèses de maturation,” which contains the first description of the chiasma structure. He observed that, of the four chromatids present at the connection sites (chiasmata sites) at diplotene or anaphase of the first meiotic division, two crossed each other and two did not. He therefore postulated that the maternal and paternal chromatids that crossed penetrated the other until they broke and rejoined in maternal and paternal segments new ways; the other two chromatids remained free and thus intact. -

Timeline Code Dnai Site Guide

DNAi Site Guide 1 DNAi Site Guide Timeline Pre 1920’s Johann Gregor Mendel, Friedrich Miescher, Carl Erich Correns, Hugo De Vries, Erich Von Tschermak- Seysenegg, Thomas Hunt Morgan 1920-49 Hermann Muller, Barbara McClintock, George Wells Beadle, Edward Lawrie Tatum, Joshua Lederberg, Oswald Theodore Avery 1950-54 Erwin Chargaff, Rosalind Elsie Franklin, Martha Chase, Alfred Day Hershey, Linus Pauling, James Dewey Watson, Francis Harry Compton Crick, Seymour Benzer 1955-59 Francis Harry Compton Crick, Paul Charles Zamecnik, Mahlon Hoagland, Matthew Stanley Meselson, Franklin William Stahl, Arthur Kornberg 1960’s Sydney Brenner, Marshall Warren Nirenberg, François Jacob, Jacques Lucien Monod, Roy John Britten 1970’s David Baltimore, Howard Martin Temin, Stanley Norman Cohen, Herbert W. Boyer, Richard John Roberts, Phillip Allen Sharp, Roger Kornberg, Frederick Sanger 1980’s Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard, Eric Francis Wieschaus, Kary Mullis, Thomas Robert Cech, Sidney Altman, Mario Renato Capecchi 1990-2000 Mary-Claire King, Stephen P.A. Fodor, Patrick Henry Brown, John Craig Venter Francis Collins, John Sulston Code Finding the structure Problem What is the structure of DNA? DNAi Site Guide 2 Players Erwin Chargaff, Rosalind Franklin, Linus Pauling, James Watson and Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins Pieces of the puzzle Wilkins' X-ray, Pauling's triple helix, Franklin's X-ray, Watson's base pairing, Chargaff's ratios Putting it together DNA is a double-stranded helix. Copying the code Problem How is DNA copied? Players James Watson and Francis Crick, Sydney Brenner, François Jacob, Matthew Meselson, Arthur Kornberg Pieces of the puzzle The Central Dogma, Semi-conservative replication Models of DNA replication, The RNA experiment, DNA synthesis Putting it together DNA is used as a template for copying information. -

Investigating DNA Replication”

Sample student results, Student Sheet 8.1, “Investigating DNA Replication” p. 100 Science and Global Issues (SGI) Genetics: Feeding the World Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl’s Experiment to Investigate DNA Replication First: Scientists James Watson and Francis Crick propose a method of semi-conservative replication in their paper on the structure of DNA. However, they have no data to support their hypothesis. Next: Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl use the procedure that follows to investigate DNA created by the process of DNA Replication. Procedure 1. Place bacteria, Escherichia coli (E. coli) in a solution of “heavy” nitrogen. 2. Leave the E. coli in the “heavy” nitrogen solution until all DNA nucleotides, and all DNA strands, are made of “heavy” nitrogen. This is Generation Zero. 3. Isolate the DNA from the E. coli. 4. Place “heavy” DNA in a solution with the same density as DNA. Genetics Transparency 8.1a ©2008 The Regents of the University of California p. 107 Science and Global Issues (SGI) Genetics: Feeding the World 5. Run “heavy” DNA solution on a centrifuge. A band of “heavy” DNA forms in the test tube. 6. Transfer some of the E. coli with “heavy” DNA into a solution of “light” DNA. 7. Allow the E. coli to reproduce for 20 minutes (the reproduction time of E. coli). 8. Place E. coli in the solution and run the tube on a centrifuge. 9. Analyze the bands of DNA that form. 10. Repeat for 3 rounds of Replication. 11. Compare the bands that form for each round of replication. Genetics Transparency 8.1b ©2008 The Regents of the University of California p.