Odyseja 1961: 50 Lat Kodu Genetycznego

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A

01/08/2018 Discovery of DNA Double Helix: Watson and Crick | Learn Science at Scitable NUCLEIC ACID STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION | Lead Editor: Bob Moss Discovery of DNA Structure and Function: Watson and Crick By: Leslie A. Pray, Ph.D. © 2008 Nature Education Citation: Pray, L. (2008) Discovery of DNA structure and function: Watson and Crick. Nature Education 1(1):100 The landmark ideas of Watson and Crick relied heavily on the work of other scientists. What did the duo actually discover? Aa Aa Aa Many people believe that American biologist James Watson and English physicist Francis Crick discovered DNA in the 1950s. In reality, this is not the case. Rather, DNA was first identified in the late 1860s by Swiss chemist Friedrich Miescher. Then, in the decades following Miescher's discovery, other scientists--notably, Phoebus Levene and Erwin Chargaff--carried out a series of research efforts that revealed additional details about the DNA molecule, including its primary chemical components and the ways in which they joined with one another. Without the scientific foundation provided by these pioneers, Watson and Crick may never have reached their groundbreaking conclusion of 1953: that the DNA molecule exists in the form of a three-dimensional double helix. The First Piece of the Puzzle: Miescher Discovers DNA Although few people realize it, 1869 was a landmark year in genetic research, because it was the year in which Swiss physiological chemist Friedrich Miescher first identified what he called "nuclein" inside the nuclei of human white blood cells. (The term "nuclein" was later changed to "nucleic acid" and eventually to "deoxyribonucleic acid," or "DNA.") Miescher's plan was to isolate and characterize not the nuclein (which nobody at that time realized existed) but instead the protein components of leukocytes (white blood cells). -

Biochemistrystanford00kornrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Program in the History of the Biosciences and Biotechnology Arthur Kornberg, M.D. BIOCHEMISTRY AT STANFORD, BIOTECHNOLOGY AT DNAX With an Introduction by Joshua Lederberg Interviews Conducted by Sally Smith Hughes, Ph.D. in 1997 Copyright 1998 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Arthur Kornberg, M.D., dated June 18, 1997. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

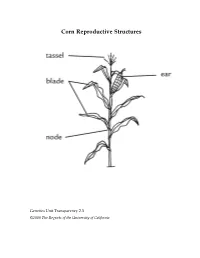

Corn Reproductive Structures

Corn Reproductive Structures Genetics Unit Transparency 2.3 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Creating a Punnett Square Genetics Unit Transparency 2.4 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Case Study Summary Sheet Case Study Type of Benefits Risks and concerns Remaining questions Genetic Modification Genetics Unit Transparency 4.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Class Data for Rice Breeding Simulation aromatic, non-aromatic, aromatic, non-aromatic ,flood-tolear nt flood-tolerant flood-intolerant flood-intolerant AAFF AAFf AaFF AaFf aaFF aaFf AAff Aaff aaff Group 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Genetics Unit Transparency 5.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Three Types of Cells Genetics Unit Transparency 6.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California DNA base percentages in a variety of organisms Source of A T G C DNA Human 31.0% 31.5% 19.1% 18.4% Mouse 29.1% 29.0% 21.1% 21.1% Frog 26.3% 26.4% 23.5% 23.8% Fruit fly 27.3% 27.6% 22.5% 22.5% Corn 25.6% 25.3% 24.5% 24.6% E. coli 24.6% 24.3% 25.5% 25.6% Genetics Unit Transparency 7.1 ©2008 The Regents of the University of California Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl’s Experiment to Investigate DNA Replication First: Scientists James Watson and Francis Crick propose a method of semi-conservative replication in their paper on the structure of DNA. However, they have no data to support their hypothesis. Next: Matthew Meselson and Franklin Stahl use the procedure that follows to investigate DNA created by the process of DNA Replication. -

Asilomar Conference on Laboratory Precautions When Conducting Recombinant DNA Research – Case Summary M.J

International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering Case Study Series Asilomar Conference on Laboratory Precautions When Conducting Recombinant DNA Research – Case Summary M.J. Peterson with research assistance from Paul White Version 1, June 2010 Safe laboratory practices are an important element in the responsible conduct of research. They protect scientists, research assistants, laboratory technicians, and others from hazards that can arise during experimentation. The particular hazards that might arise vary according to the type of experimentation: the explosions or toxic gases that could result from chemical experiments are prevented or contained by different kinds of measures then are used to limit the health hazards posed by working with radioactive isotopes. In most areas, scientists are allowed – and even encouraged – to decide for themselves what experiments to undertake and how to construct and run their labs. In 1970, there were three main exceptions, and they applied more to questions of how to carry out research than to selecting topics for research: use of radioactive materials, use of tumor-causing viruses, and use of human subjects. In these areas, levels of risk to persons inside and outside the lab were perceived as great enough to justify having the government, either through the regular bureaucracy or through scientific agencies, set and enforce mandatory safety standards. When genetics was poised at the threshold of recombinant DNA research and genetic manipulation techniques in the 1960s, the hazards such work might pose to lab personnel or to others were unknown. Many scientists and others believed they were likely to be significant. The primary concern in public discussion was whether hybrid organisms bred from recombinant DNA would cause new diseases or create varieties of plants or animals that would overwhelm and irretrievably change the natural environment. -

1 History for Canonical and Non-Canonical Structures of Nucleic Acids

1 1 History for Canonical and Non-canonical Structures of Nucleic Acids The main points of the learning: Understand canonical and non-canonical structures of nucleic acids and think of historical scientists in the research field of nucleic acids. 1.1 Introduction This book is to interpret the non-canonical structures and their stabilities of nucleic acids from the viewpoint of the chemistry and study their biological significances. There is more than 60 years’ history after the discovery of the double helix DNA structure by James Dewey Watson and Francis Harry Compton Crick in 1953, and chemical biology of nucleic acids is facing a new aspect today. Through this book, I expect that readers understand how the uncommon structure of nucleic acids became one of the common structures that fascinate us now. In this chapter, I introduce the history of nucleic acid structures and the perspective of research for non-canonical nucleic acid structures (see also Chapter 15). 1.2 History of Duplex The opening of the history of genetics was mainly done by three researchers. Charles Robert Darwin, who was a scientist of natural science, pioneered genetics. The proposition of genetic concept is indicated in his book On the Origin of Species published in 1859. He indicated the theory of biological evolution, which is the basic scientific hypothesis of natural diversity. In other words, he proposed biological evolution, which changed among individuals by adapting to the environment and be passed on to the next generation. However, that was still a primitive idea for the genetic concept. After that, Gregor Johann Mendel, who was a priest in Brno, Czech Republic, confirmed the mechanism of gene evolution by using “factor” inherited from parent to children using pea plant in 1865. -

DNA: the Timeline and Evidence of Discovery

1/19/2017 DNA: The Timeline and Evidence of Discovery Interactive Click and Learn (Ann Brokaw Rocky River High School) Introduction For almost a century, many scientists paved the way to the ultimate discovery of DNA and its double helix structure. Without the work of these pioneering scientists, Watson and Crick may never have made their ground-breaking double helix model, published in 1953. The knowledge of how genetic material is stored and copied in this molecule gave rise to a new way of looking at and manipulating biological processes, called molecular biology. The breakthrough changed the face of biology and our lives forever. Watch The Double Helix short film (approximately 15 minutes) – hyperlinked here. 1 1/19/2017 1865 The Garden Pea 1865 The Garden Pea In 1865, Gregor Mendel established the foundation of genetics by unraveling the basic principles of heredity, though his work would not be recognized as “revolutionary” until after his death. By studying the common garden pea plant, Mendel demonstrated the inheritance of “discrete units” and introduced the idea that the inheritance of these units from generation to generation follows particular patterns. These patterns are now referred to as the “Laws of Mendelian Inheritance.” 2 1/19/2017 1869 The Isolation of “Nuclein” 1869 Isolated Nuclein Friedrich Miescher, a Swiss researcher, noticed an unknown precipitate in his work with white blood cells. Upon isolating the material, he noted that it resisted protein-digesting enzymes. Why is it important that the material was not digested by the enzymes? Further work led him to the discovery that the substance contained carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen and large amounts of phosphorus with no sulfur. -

Structure of DNA &

Structure Of DNA & RNA By Himanshu Dev VMMC & SJH DNA DNA Deoxyribonucleic acid DNA - a polymer of deoxyribo- nucleotides. Usually double stranded. And have double-helix structure. found in chromosomes, mitochondria and chloroplasts. It acts as the genetic material in most of the organisms. Carries the genetic information A Few Key Events Led to the Discovery of the Structure of DNA DNA as an acidic substance present in nucleus was first identified by Friedrich Meischer in 1868. He named it as ‘Nuclein’. Friedrich Meischer In 1953 , James Watson and Francis Crick, described a very simple but famous Double Helix model for the structure of DNA. FRANCIS CRICK AND JAMES WATSON The scientific framework for their breakthrough was provided by other scientists including Linus Pauling Rosalind Franklin and Maurice Wilkins Erwin Chargaff Rosalind Franklin She worked in same laboratory as Maurice Wilkins. She study X-ray diffraction to study wet fibers of DNA. X-ray diffraction of wet DNA fibers The diffraction pattern is interpreted X Ray (using mathematical theory) Crystallography This can ultimately provide Rosalind information concerning the structure Franklin’s photo of the molecule She made marked advances in X-ray diffraction techniques with DNA The diffraction pattern she obtained suggested several structural features of DNA Helical More than one strand 10 base pairs per complete turn Rosalind Franklin Maurice Wilkins DNA Structure DNA structure is often divided into four different levels primary, secondary, tertiary -

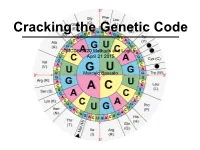

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

JESSICA L. MARK WELCH Assistant Research Scientist Josephine Bay

JESSICA L. MARK WELCH Assistant Research Scientist Josephine Bay Paul Center, Marine Biological Laboratory 7 MBL Street, Woods Hole, MA 02543 Telephone (508) 289-7180, e-mail [email protected] EDUCATION: B.A. magna cum laude, Harvard and Radcliffe Colleges, Biology, 1989 Graduate work, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany, Chemistry and Biology, 1990-1992 Advisor: Walter Sudhaus Ph.D., Harvard University Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Biology, 2001 Advisor: Matthew Meselson. Dissertation topic: Cytological Evidence for the Absence of Meiosis in Bdelloid Rotifers. Postdoctoral training, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Molecular Biology 2001-2006 part-time 2006-2009 full-time Advisors: Matthew Meselson and Gary Borisy PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS: 1989 – 1990 Research Assistant, Environmental Law Institute, Washington, DC 2009 – present Assistant Research Scientist, Josephine Bay Paul Center for Comparative Molecular Biology and Evolution, Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, MA. PUBLICATIONS: Valm, Alex M., Jessica L. Mark Welch, and Gary G. Borisy (2012). CLASI-FISH: Principles of Combinatorial Labeling and Spectral Imaging. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 2012 Apr 21 (Epub ahead of print). PMCID: PMC3407316. Sukenik, Assaf, Ruth N. Kaplan-Levy, Jessica Mark Welch, and Anton Post (2011). Massive multiplication of genome and ribosomes in dormant cells (akinetes) of Aphanizomenon ovalisporum (Cyanobacteria). The ISME Journal 2011.128 (epub ahead of print, October 6, 2011). Valm, Alex M., Jessica L. Mark Welch, Christopher W. Rieken, Yuko Hasegawa, Mitchell L. Sogin, Rudolf Oldenbourg, Floyd E. Dewhirst, and Gary G. Borisy (2011). Systems-level analysis of microbial community organization through combinatorial labeling and spectral imaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA) 108: 4152-4157. -

Maxine Singer, Date? (Sometime in Early 2015)

Oral History: Maxine Singer, date? (sometime in early 2015) CAF: Alright Donald, why don’t you start DPS: Well, when did you meet Caryl, Caryl Haskins and how did this meeting come about? MS: I think, but I’m not really sure, that the first time I met him might have been at a Yale Corporation meeting, and it was probably 1975, if I have to guess, because that’s when I went on the corporation. And he had already been a member. So I’m pretty sure I met him at that meeting. DPS: OK. I’ll go on. We have a record of his activities as President of the Carnegie Institution. What would you regard as the facets of his leadership that were most revealing about him? MS: Well, I think the most revealing thing about him was the fact that he convinced the trustees to close down the Department of Genetics. So: Could you remind me what years he was president? DPS: ’56 to ’71, I believe. MS: Right. So I think the…In my judgment anyway. Maybe other people would feel differently. But in my judgment, that was the single, most important thing he did. CAF: Why is that? DPS: What led him to do that? MS: So this is a good, an interesting question about which we have only fragmentary knowledge. The long time director of the department, whose name was Demerec, retired. And Demerec was a classical geneticist, which is something that Caryl understood. And the people who were coming up, and even some of the people who there, were beginning to study genetics as a molecular science, tied to biochemistry in various ways, which was certainly the new world and the world of science that proved to be incredibly productive. -

The Gene Wars: Science, Politics, and the Human Genome

8 Early Skirmishes | N A COMMENTARY introducing the March 7, 1986, issue of Science, I. Renato Dulbecco, a Nobel laureate and president of the Salk Institute, made the startling assertion that progress in the War on Cancer would be speedier if geneticists were to sequence the human genome.1 For most biologists, Dulbecco's Science article was their first encounter with the idea of sequencing the human genome, and it provoked discussions in the laboratories of universities and research centers throughout the world. Dul- becco was not known as a crusader or self-promoter—quite the opposite— and so his proposal attained credence it would have lacked coming from a less esteemed source. Like Sinsheimer, Dulbecco came to the idea from a penchant for thinking big. His first public airing of the idea came at a gala Kennedy Center event, a meeting organized by the Italian embassy in Washington, D.C., on Columbus Day, 1985.2 The meeting included a section on U.S.-Italian cooperation in science, and Dulbecco was invited to give a presentation as one of the most eminent Italian biologists, familiar with science in both the United States and Italy. He was preparing a review paper on the genetic approach to cancer, and he decided that the occasion called for grand ideas. In thinking through the recent past and future directions of cancer research, he decided it could be greatly enriched by a single bold stroke—sequencing the human genome. This Washington meeting marked the beginning of the Italian genome program.3 Dulbecco later made the sequencing -

Members of Groups Central to the Scientists' Debates About Rdna

International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering Case Study Series: Asilomar Conference on Laboratory Precautions Appendix C: Members of Groups Central to the Scientists’ Debates about rDNA Research 1973-76 M.J. Peterson Version 1, June 2010 Signers of Singer-Söll Letter 1973 Maxine Singer Dieter Söll Signers of Berg Letter 1974 Paul Berg David Baltimore Herbert Boyer Stanley Cohen Ronald Davis David S. Hogness Daniel Nathans Richard O. Roblin III James Watson Sherman Weissman Norton D. Zinder Organizing Committee for the Asilomar Conference David Baltimore Paul Berg Sydney Brenner Richard O. Roblin III Maxine Singer This case was created by the International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering (IDEESE) Project at the University of Massachusetts Amherst with support from the National Science Foundation under grant number 0734887. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. More information about the IDEESE and copies of its modules can be found at http://www.umass.edu/sts/ethics. This case should be cited as: M.J. Peterson. 2010. “Asilomar Conference on Laboratory Precautions When Conducting Recombinant DNA Research.” International Dimensions of Ethics Education in Science and Engineering. Available www.umass.edu/sts/ethics. © 2010 IDEESE Project Appendix C Working Groups for the Asilomar Conference Plasmids Richard Novick (Chair) Royston C. Clowes (Institute for Molecular Biology, University of Texas at Dallas) Stanley N. Cohen Roy Curtiss III Stanley Falkow Eukaryotes Donald Brown (Chair) Sydney Brenner Robert H. Burris (Department of Biochemistry, University of Wisconsin) Dana Carroll (Department of Embryology, Carnegie Institution, Baltimore) Ronald W.