Leslie E. Orgel 1927–2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Andrew Wiles Building: a Short History Below: Charles L

Nick Woodhouse The Andrew Wiles Building: A short history Below: Charles L. Dodgson A short time in the life of the University (Lewis Carroll) aged 24 at his “The opening of this desk [Wakeling Collection] The earliest ‘mathematical institute’ in Oxford fantastic building is may have been the School of Geometry and Arithmetic in the main Quadrangle of the great news for Oxford’s Bodleian Library (completed in 1620). But it was clearly insufficient to provide space staff and students, who for everyone. In 1649, a giant of Oxford mathematics, John Wallis, was elected to the will soon be learning Savilian Chair of Geometry. As a married man, he could not hold a college fellowship and he together in a stunning had no college rooms. He had to work from rented lodgings in New College Lane. new space.” In the 19th century, lectures were mainly given in colleges, prompting Charles Dodgson Rt Hon David Willets MP (Lewis Carroll) to write a whimsical letter to Minister of State for Universities and Science the Senior Censor of Christ Church. After commenting on the unwholesome nature of lobster sauce and the accompanying nightmares it can produce, he remarked: ‘This naturally brings me on to the subject of Mathematics, and of the accommodation provided by the University for carrying on the calculations necessary in that important branch of science.’ He continued with a detailed set of specifications, not all of which have been met even now. There was no room for the “narrow strip of ground, railed off and carefully levelled, for investigating the properties of Asymptotes, and testing practically whether Parallel Lines meet or not: for this purpose it should reach, to use the expressive language of Euclid, ‘ever so far’”. -

Download This Article in PDF Format

BIO Web of Conferences 4, 00014 (2015) DOI: 10.1051/bioconf/20150400014 C Owned by the authors, published by EDP Sciences, 2015 From neonts to filionts and their progenies... Biodiversity draws its origins from the origins of life itself Marie-Christine Maurela Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB - UMR 7205 – CNRS, MNHN, UPMC, EPHE), Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Sorbonne Universités, 45 rue Buffon, CP. 50, 75005 Paris, France “Should the question of the priority of the egg over the chicken, or of the chicken over the egg disturb you, it is because you assume that animals were originally what they are to-day; what madness!" The dream of d’Alembert, 1760, Denis Diderot Abstract. Since the origins, different modes of life exist. Indeed it is difficult to imagine how things could have been constructed by a single event that would have marked the birth of life. A brief historical background of the subject will be presented here. Then, we shall wander through the history of the discoveries that have led the way of experimental science over the last 150 years and shall dwell on one of the major paradigms, that of the RNA World. This paradigm illustrates the path followed by the living that tries all possible means when expressed at the molecular level as simple free molecule leading to RNA fragments and to modern subviral particles such as viroids then to ramifications and compartments. Between the ancient and the modern RNA world we underline how environment talks to molecules leading to the global living tissus which establish the ground of biodiversity. -

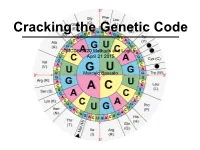

MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo

Cracking the Genetic Code MCDB 5220 Methods and Logics April 21 2015 Marcelo Bassalo The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) Frederick Griffith The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) Oswald Avery Alfred Hershey Martha Chase The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) Linus Carl Pauling The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) James Watson and Francis Crick The DNA Saga… so far Important contributions for cracking the genetic code: • The “transforming principle” (1928) • The nature of the transforming principle: DNA (1944 - 1952) • X-ray diffraction and the structure of proteins (1951) • The structure of DNA (1953) How is DNA (4 nucleotides) the genetic material while proteins (20 amino acids) are the building blocks? ? DNA Protein ? The Coding Craze ? DNA Protein What was already known? • DNA resides inside the nucleus - DNA is not the carrier • Protein synthesis occur in the cytoplasm through ribosomes {• Only RNA is associated with ribosomes (no DNA) - rRNA is not the carrier { • Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was a homogeneous population The “messenger RNA” hypothesis François Jacob Jacques Monod The Coding Craze ? DNA RNA Protein RNA Tie Club Table from Wikipedia The Coding Craze Who won the race Marshall Nirenberg J. -

Tributions in Two Separate fields—Theoretical Chemistry and Artificial Intelligence

Christopher Longuet-Higgins Hugh Christopher Longuet-Higgins was an outstanding scientist who made lasting con- tributions in two separate fields—theoretical chemistry and artificial intelligence. He was an applied mathematician of exceptional gifts, whose ability to see to the mathematical heart of a scientific problem transcended all disciplinary boundaries. He is survived by his younger brother Michael, who is a distinguished geophysicist Christopher was born in Kent, the second of three children of the Reverend Henry Hugh Longuet-Higgins, and Albinia Cecil Longuet-Higgins, n´ee Bazeley. He was edu- cated at Winchester (where he was a contemporary of Freeman Dyson, whose brilliance in physics he said led him to avoid going in for that subject) and at Oxford, where he studied both music and chemistry. (While his career lay in science, he was also an exceptionally fine pianist, capable of brilliant improvisation in the late romantic style, with a deep love and understanding of music that sustained him throughout his life.) While still an undergraduate, he published an important paper with his tutor Ronald Bell on the structure of diborane, from which several subsequently confirmed predictions concerning the existence and structure of similarly electron-deficient molecules followed. Later, he provided an analysis for the structure in terms of a novel type of bond whose existence he proved on the basis of Mulliken's molecular orbital theory, and which led to a complete analysis of the structure of the boranes. This work formed part of his PhD at Oxford under Charles Coulson, a pioneer in applying statistical and quantum mechanics to the analysis of molecular structure. -

Curriculum Vitaecv (PDF)

Laura Gagliardi April 2020 CURRICULUM VITAE LAURA GAGLIARDI CURRENT PROFESSIONAL ADDRESS Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota 207 Pleasant St. SE (Office 229) Minneapolis, MN 55455-0431 Phone: (612) 625-8299 Email: [email protected] Web page: http://www.chem.umn.edu/groups/gagliardi ACADEMIC RANK McKnight Presidential Endowed Chair, Distinguished McKnight University Professor, Professor of Chemistry, and Graduate Faculty Appointment in Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, University of Minnesota EDUCATION Degree Institution Degree Granted M.A./M.S. University of Bologna, Italy 1992 Ph.D./J.D. University of Bologna, Italy 1997 [Ph.D. advisor: Gian Luigi Bendazzoli] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE University of Minnesota McKnight Presidential Endowed Chair 2019-present Distinguished McKnight University Professor 2014-present Professor 2009-present Director, Inorganometallic Catalyst Design Center EFRC 2014-present Graduate Appointment in Chemical Engineering and Materials Science 2012-present Director, Chemical Theory Center 2012-present Director, Nanoporous Materials Genome Center 2012 - 2014 Previous Employment Associate Professor, University of Geneva (Switzerland) 2005 - 2009 Assistant Professor, University of Palermo (Italy) 2000 - 2004 Postdoctoral Appointments University of Cambridge (U.K.) 1998 - 2000 Graduate Appointments University of Bologna (Italy) 1993 - 1997 1 Laura Gagliardi April 2020 RESEARCH INTERESTS AND EXPERTISE Development of novel quantum chemical methods for strongly correlated systems. Combination of first principle methods with classical simulation techniques. The applications are focused on the computational design of novel materials and molecular systems for energy-related challenges. Special focus is devoted to modeling catalysis and spectroscopy in molecular systems; catalysis and gas separation in porous materials; photovoltaic properties of organic and inorganic semiconductors; separation of actinides. -

Wo 2012/064675 A2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date - if 18 May 2012 (18.05.2012) WO 2012/064675 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every C12N 15/11 (2006.01) C12Q 1/68 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, C07H 21/00 (2006.01) C12N 15/10 (2006.01) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (21) International Application Number: DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, PCT/US201 1/059656 HN, HR, HU, ID, JL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, (22) International Filing Date: KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, 7 November 20 11 (07.1 1.201 1) ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, (25) Filing Language: English RW, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, (26) Publication Language: English TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: 61/41 1,974 10 November 2010 (10.1 1.2010) US (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (72) Inventor; and GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, (71) Applicant : WEBB, Nigel, L. -

The Eightfold Path to Non-Enzymatic RNA Replication Jack W Szostak

Szostak Journal of Systems Chemistry 2012, 3:2 http://www.jsystchem.com/content/3/1/2 PERSPECTIVES Open Access The eightfold path to non-enzymatic RNA replication Jack W Szostak Abstract The first RNA World models were based on the concept of an RNA replicase - a ribozyme that was a good enough RNA polymerase that it could catalyze its own replication. Although several RNA polymerase ribozymes have been evolved in vitro, the creation of a true replicase remains a great experimental challenge. At first glance the alternative, in which RNA replication is driven purely by chemical and physical processes, seems even more challenging, given that so many unsolved problems appear to stand in the way of repeated cycles of non- enzymatic RNA replication. Nevertheless the idea of non-enzymatic RNA replication is attractive, because it implies that the first heritable functional RNA need not have improved replication, but could have been a metabolic ribozyme or structural RNA that conferred any function that enhanced protocell reproduction or survival. In this review, I discuss recent findings that suggest that chemically driven RNA replication may not be completely impossible. Keywords: Non-enzymatic replication, RNA World, protocell, origin of life, prebiotic chemistry, fidelity 1. Introduction assembly of ribonucleotides and RNA oligomers will Considerable evidence supports the RNA World hypoth- eventually be found. esis of an early phase of life, prior to the evolution of Unfortunately, even given prebiotically generated RNA coded protein synthesis, in which cellular biochemistry templates and abundant ribonucleotides, we do not under- and genetics were largely the province of RNA (reviewed stand how cycles of template-directed RNA replication in [1,2]). -

Panspermia — the Theory That Life Came from Outer Space

CEN Tech. J., vol. 7(1), 1993, pp. 82–87 Panspermia — The Theory that Life came from Outer Space DR JERRY BERGMAN ABSTRACT In debates about the creation-evolution controversy, many evolutionists allege that the existing naturalistic origin of life theory is generally regarded as highly possible. That these theories are in fact not tenable is shown by the fact that many prominent evolutionists now hypothesize an alternate method. Since the theistic world view is unacceptable, they thus assume a set of conditions elsewhere in the solar system or the universe which are theorized to be more favourable for the origin of life. The recognition that the conditions on the earth are such that the origin of life is close to impossible forces this approach if a naturalistic world view is maintained. Nowhere does the literature reveal as vividly the impossibility of a naturalistic origin of life on the earth than in this area. The fact that an entirely hypothetical scenario has been proposed which is supported by virtually no evidence and only, at best, indirect inferences which can be interpreted as evidence, forces a review of the theory of panspermia. Much science fiction has in time become science fact — journeying to the moon, for example —and this should not surprise us. Many science fiction writers are scientists by profession, or at least trained in science at the graduate level. Isaac Asimov, a Ph.D. in biochemistry, is the best known example. Writing good science fiction requires both a good grasp of science fact and a vivid imagination. One of the latest science fictions which is now becoming ‘respectable’ science theory is panspermia, the belief that the source of life on earth was from other worlds. -

Pauling's Defence of Bent-Equivalent Bonds

Pauling’s Defence of Bent-Equivalent Bonds: A View of Evolving Explanatory Demands in Modern Chemistry Summary Linus Pauling played a key role in creating valence-bond theory, one of two competing theories of the chemical bond that appeared in the first half of the 20th century. While the chemical community preferred his theory over molecular-orbital theory for a number of years, valence-bond theory began to fall into disuse during the 1950s. This shift in the chemical community’s perception of Pauling’s theory motivated Pauling to defend the theory, and he did so in a peculiar way. Rather than publishing a defence of the full theory in leading journals of the day, Pauling published a defence of a particular model of the double bond predicted by the theory in a revised edition of his famous textbook, The Nature of the Chemical Bond. This paper explores that peculiar choice by considering both the circumstances that brought about the defence and the mathematical apparatus Pauling employed, using new discoveries from the Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers archive. Keywords: Linus Pauling, Chemical Bond, Double Bond, Chemistry, Valence, Resonance, Explanation, Chemical Education Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………….. 2 2. Using Valence Bonds and Molecular Orbitals to Explain the Double Bond………………………………………………………................. 3 3. Textbook Explanations……………………………………………… 5 4. The Origins of Bent-Equivalent Bonds ……………………..……… 7 4.1 An Early Defence …………………………………………….. 8 5. Catalysing the Mature Defence……………………………………… 9 5.1 Soviet Suppression and Pedagogical Disfavour ………………. 11 5.2 Wilson…………………………………………………………. 12 5.3 Kekulé…………………………………………………………. 14 6. Concentrating Bond Orbitals into a Defence………………………… 15 7. Conclusions………………………………………………………….. 17 Word Count: 8658 (9936 with footnotes) Pauling’s Defence of Bent-Equivalent Bonds Page 2 of 19 1. -

A Deeper Look at the Origin of Life by Bob Davis

A Deeper Look at the Origin of Life By Bob Davis Every major society from every age in history has had its own story about its origins. For instance, the Eskimos attributed their existence to a raven. The ancient Germanic peoples of Scandinavia believed their creator—Ymir—emerged from ice and fire, was nourished by a cow, and ultimately gave rise to the human race. Those are just two examples. But no matter the details, these origin stories always endeavor to answer people’s innate questions: Where did we come from? What is our destiny? What is our purpose? Two widely held theories in today’s world are abiogenesis and the Genesis story. The first states that life emerged through nature without any divine guidance; the second involves a supernatural Creator. Abiogenesis Abiogenesis is sometimes called “chemical evolution” because it seeks to explain how non-living (“abio”) substances gave rise to life (“genesis”). Abiogenesis was added to the list of origin stories over one hundred years ago when Charles Darwin first speculated that life could have begun in a “warm little pond, with all sorts of ammonia and phosphoric salts, lights, heat, electricity, etc. present, so that a protein compound was chemically formed ready to undergo still more complex changes.”1 Many summarize abiogenesis—coupled with its more famous twin, Darwinian macroevolution—in a somewhat disparaging but memorable way: “From the goo to you by way of the zoo!”2 Let’s use this phrase to help us understand what is meant by “abiogenesis.” The “goo” refers to the “primordial soup” or “warm little pond” where non-life is said to have given birth to life. -

Francis Crick Personal Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1k40250c No online items Francis Crick Personal Papers Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego Copyright 2007, 2016 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 [email protected] URL: http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/index.html Francis Crick Personal Papers MSS 0660 1 Descriptive Summary Languages: English Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla 92093-0175 Title: Francis Crick Personal Papers Creator: Crick, Francis Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0660 Physical Description: 14.6 Linear feet(32 archives boxes, 4 card file boxes, 2 oversize folders, 4 map case folders, and digital files) Physical Description: 2.04 Gigabytes Date (inclusive): 1935-2007 Abstract: Personal papers of British scientist and Nobel Prize winner Francis Harry Compton Crick, who co-discovered the helical structure of DNA with James D. Watson. The papers document Crick's family, social and personal life from 1938 until his death in 2004, and include letters from friends and professional colleagues, family members and organizations. The papers also contain photographs of Crick and his circle; notebooks and numerous appointment books (1946-2004); writings of Crick and others; film and television projects; miscellaneous certificates and awards; materials relating to his wife, Odile Crick; and collected memorabilia. Scope and Content of Collection Personal papers of Francis Crick, the British molecular biologist, biophysicist, neuroscientist, and Nobel Prize winner who co-discovered the helical structure of DNA with James D. Watson. The papers provide a glimpse of his social life and relationships with family, friends and colleagues. -

The Origins of Cellular Life

Downloaded from http://cshperspectives.cshlp.org/ on October 1, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press The Origins of Cellular Life Jason P. Schrum, Ting F. Zhu, and Jack W. Szostak Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Department of Molecular Biology and the Center for Computational and Integrative Biology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 02114 Correspondence: [email protected] Understanding the origin of cellular life on Earth requires the discovery of plausible pathways for the transition from complex prebiotic chemistry to simple biology,defined asthe emergence of chemical assemblies capable of Darwinian evolution. We have proposed that a simple primitive cell, or protocell, would consist of two key components: a protocell membrane that defines a spatially localized compartment, and an informational polymer that allows for the replication and inheritance of functional information. Recent studies of vesicles composed of fatty-acid membranes have shed considerable light on pathways for protocell growth and division, as well as means by which protocells could take up nutrients from their environment. Additional work with genetic polymers has provided insight into the potential for chemical genome replication and compatibility with membrane encapsulation. The integration of a dynamic fatty-acid compartment with robust, generalized genetic polymer replication wouldyield a laboratory model of a protocell with the potential forclassical Darwinian biologi- cal evolution, and may help to evaluate potential pathways for the emergence of life on the early Earth. Here we discuss efforts to devise such an integrated protocell model. he emergence of the first cells on the early membrane-encapsulated nucleic acids, and the TEarth was the culmination of a long history chemical and physical processes that allowed of prior chemical and geophysical processes.