SF COMMENTARY 82 40Th Anniversary Edition, Part 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hitler's Pope

1ews• Hitler's Pope Since last Christmas, GOOD SHEPHERD has assisted: - 103 homeless people to find permanent accommodation; - 70 young people to find foster care; - 7S7 families to receive financial counselling; - 21 9 people through a No Interest Loan (N ILS); Art Monthly - 12 adolescent mothers to find a place to live with support; .-lUSTR .-l/,/. 1 - 43 single mothers escaping domestic violence to find a safe home for their families; - 1466 adolescent s through counselling: - 662 young women and their families, I :\' T H E N 0 , . E '1 B E R I S S L E through counsell ing work and Reiki; - hundreds of families and Patrick I lutching;s rC\ie\\s the Jeffrey Smart retruspecti\e individuals through referrals, by speaking out against injustices and by advocating :\mire\\ Sa\ ers talks to I )a\ id I lockney <lhout portraiture on their behalf. Sunnne Spunn~:r trac~:s tht: )!t:nt:alo g;y of the Tclstra \:ational .\horig;inal and Torres Strait Islander :\rt .\"ani \bry Eag;k rt:\it:\\S the conti:rmct: \\'hat John lkrg;t:r Sa\\ Christopher I leathcott: on Australian artists and em ironm~:ntal awart:nt:ss Out now S-1. 1/'i, ji·ll/1/ g lllld 1/(/llhl/llf>S 111/d 1/ t' II ' S i /. ~t' II/S. Or plulllt' IJl fJl.J'J .i'JSfJ ji1 r your su/>stnf>/11111 AUSTRALIAN "Everyone said they wanted a full church. What I discovered was that whil e that was true, they di dn't BOOK REVIEW want any new people. -

The Language of Astonishment: a French-Australian Author's

THE LANGUAGE OF ASTONISHMENT: A FRENCH-AUSTRALIAN AUTHOR’S REFLECTIONS ON HER IDENTITY SOPHIE MASSON Towards the end of Russian-French writer Andreï Makine’s hauntingly beautiful novel of childhood, memory and divided loyalties, Le Testament français (1995), the narrator Alyosha, who all his young life has been shuttling between the visceral reality of his Russian Siberian childhood and his French grandmother’s poetic evocations of her past and her old country, has a sudden slip of the tongue which for a moment puts him in a disorienting position: that of being literally between two languages, between French and Russian, and understood in neither. But it is that very moment which transforms his life and his understanding of himself and his literary ambitions. The gap between the two languages, which as a dreamy child he simply accepted and as a rebellious teenager he reacted against, is not what he once thought it was—a frustrating barrier to understanding or a comforting bulwark against reality, depending on his mood at the time. No, it is something far stranger and much more exhilarating: a prism through which everything can be seen and felt even more clearly, sensually and intensely and not only because with two languages at your disposal you have even more opportunity to ‘nail’ the world, as it were. It is also because this between-two-languages phenomenon, common to all bilingual people, is actually a striking metaphor for the gap that exists between language per se and language lived—the sensual reality for all human beings. And it is in that gap that literature itself is born: literature which, in Makine’s beautiful words, is un étonnement permanent devant cette coulée verbale dans laquelle fondait le monde (Makine, 244).1 And it is that very ‘in-between’, that universal ‘language of astonishment’, which will turn Alyosha into a writer and by extension Makine himself, who included many autobiographical elements in the novel. -

A Current Listing of Contents

WOMEN'S SruDIES LIBRARIAN The University ofWisconsin System EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS VOLUME 17, NUMBER 4 WINTER 1998 Published by Phyllis Holman Weisbard Women's Studies Librarian University of Wisconsin System 430 Memorial Library / 728 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 (608) 263-5754 EMINIST ERIODICALS A CURRENT LISTING OF CONTENTS Volume 17, Number 4 Winter 1998 Periodical literature is the cutting edge ofwomen's scholarship, feminist theory, and much ofwomen's culture. Feminist Periodicals: A Current Listing ofContents is published by the Office of the University of Wisconsin System Women's Studies Librarian on a quarterly basis with the intent of increasing public awareness of feminist periodicals. It is our hope that Feminisf Periodicals will serve several purposes: to keep the reader abreast of current topics in feminist literature; to increase readers' familiarity with a wide spectrum of feminist periodicals; and to provide the requisite bibliographic information should a reader wish to subscribe to a journal or to obtain a particular article at her library or through interlibrary loan. (Users will need to be aware of the limitations of the new copyright law with regard to photocopying of copyrighted materials.) Table ofcontents pages from currentissues ofmajorfeministjournalsare reproduced in each issue ofFeminist Periodicals, preceded by a comprehensive annotated listing of all journals we have selected. As publication schedules vary enormously, not every periodical will have table of contents pages reproduced in each issue of FP. The annotated listing provides the following information on each journal: 1. Year of first publication. 2. Frequency of publication. 3. U.S. SUbscription price(s). -

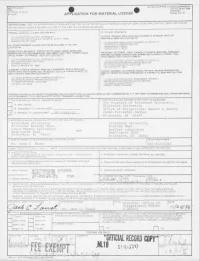

Application for Renewal of License 29-05185-25,Authorizing Use Of

- - , U,$. NUCLE AR REGULATORY COMMISSION NRC FDRM 313. APPROVED BY OMB a * 19 8M 3150 0120 10 E Pc + 3sB7 35.CFRnd ao 30,32. 33,34 AP ICATION FOR MATERIAL LICENSE INSTRUCTIONS: SEE THE APPROPRIATE LICENSE APPLICATION GUIDE FOR DETAILED INSTRUCTIONS FOR COMFLETING APPLICATION. SEND TWO COPIES OF THE ENTIRE COMPLETED APPLICATION TO THE NRC OFFICE SPECIFIED BELOW. FEDERAL AGENCIES FILE APPLICATIONS WITH: IF YOU ARE LOCATED IN ILLINOIS INDI ANA, IOW A. MICHIGAN, MINNESOT A MISSOUR1, OHIO, OR U.S NUCLE AR REGULATORY COMMISSION DIVISION OF FUEL CYCLE AND MATERIAL SAFETY,NMSS WISCONSIN, SEND APPLICATIONS TO: WASHING 4 DN, DC 20555 U.S, NUCLE AR REGULATORY COMMIS$10N, REGION ill ALL OTHER PERSONS FILE APPLICATIONS AS FOLLOWS,lF YOU ARE MATERI4.S LICENSING SECTlDN 799 ROOSEVELT ROAD LOCATEDIN: GLEN ELLYN,IL 60137 CONNECTICUT, DELAWARE , DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA MAINE. MARYLAND. MASSACHUSETTS. NEW HAMPSHIRE. NEW JERSEY, NEW YORK, PENNEYLVANIA, ARK ANSAS. COLOR ADO,lDAHO, KANSAS LOUISl AN A. MONTANA, NEBRASK A, RHOOE ISLAND, OR VERMONT, SEND APPLICATIONS 70. NEW MEXICO, NORTH DAKOTA. OK LAHOMA, SOUTH DAKOT4, TE XAS, UTAH, OR WYOMING, SEND APPLICATIONS TO: U.S. NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION, REGION I U.S NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMFSSION, REGION IV NUCLEAR MATERI AL SECTION 8 631 PARK AVENUE MATERIAL RADI ATION PROTECTION SECTION KING OF PRUSSIA,PA 19406 611 RYAN PLAZA DRIVE, SUITE 1000 ARLINGTON,TX 76011 ALABAMA, FLORIDA, GEORGIA, KENTUCKY, MISSISSIPPI, NORTH CAROLINA, PUERTO RICO, SOUTH CAROLINA, TENNESSE E, VIRGINI A, VIRGIN ISLANDS, OR AL ASK A, ARIZONA, rALIFORNI A, MAW All, NEVADA, OREGON, WASHINGTON, WEST VIRGINlA, SEND APPLICATIONS TO AND U.S. -

Data Report for Fiscal Year 2020 (Highly Compensated Report)

MTA - Data Report for Fiscal Year 2020 (Highly Compensated Report) *Last Name *First Name Middle *Title *Group School Name Highest Degree Prior Work Experience Initial O'Brien James J Mgr. Maint. Contract Admin. Managerial UNKNOWN UNKNOWN MTA Agency Berani Alban Supervising Engr Electrical Managerial CUNY City College Master of Engineering Self Employed Moravec Eva M Assistant General Counsel Professional Pace University White Plains Juris Doctor Dept. of Finance OATH Angel Nichola O AVPCenBusDisTolUnit Managerial NYU Stern School of Business Master of Mechanical Engi MTA Agency Khuu Howard N Assistant Controller Managerial Baruch College Master of Business Admin Home Box Office Reis Sergio Director Ops. Tolls & Fac. Sys Managerial Long Island University Bachelor of Science Tag Americas LLC Jacobs Daniel M Sr Dir Plan Inno&Pol Ana Managerial Rutgers University Master of Engineering MTA Agency Wilkins Alphonso Senior Safety Engineer Professional High School Diploma EnviroMed Services Inc. Walker Kellie Labor Counsel Professional Boston University Law Juris Doctor NYC Department of Education Mondal Mohammad S Supervising Engineer Structure Managerial Foreign - Non US College/Unive Bachelor Civil Engineerin Department of Buildings Friman Paul Exec Asst General Counsel Professional New York University Juris Doctor NYS Supreme Court NY Prasad Indira G Sr Project Manager TSMS Professional Stevens Institute of Technolog Master of Science Mitsui O.S.K. NY Li Bin Supervising Engineer Structure Managerial Florida International Univ Doctor of Philosophy -

Top Left-Hand Corner

The four novels Hyperion, The Fall of Hyperion, Endymion and The Rise of Endymion constitute the Hyperion Cantos by the American science fiction writer Dan Simmons. This galactic-empire, epic, science fiction narrative contains a plethora of literary references. The dominant part comes from the nineteenth-century Romantic poet John Keats. The inclusion of passages from his poetry and letters is pursued in my analysis. Employing Lubomír Doležel’s categorizations of intertextuality— “transposition,” “expansion,” and “displacement”—I seek to show how Keats’s writings and his persona constitute a privileged intertext in Simmons’s tetralogy and I show its function. Simmons constructs subsidiary plots, some of which are driven by Keats’s most well-known poetry. In consequence, some of the subplots can be regarded as rewrites of Keats’s works. Although quotations of poetry have a tendency to direct the reader’s attention away from the main plot, slowing down the narrative, such passages in the narratives evoke Keats’s philosophy of empathy, beauty and love, which is fundamental for his humanism. For Keats, the poet is a humanist, giving solace to mankind through his poetry. I argue that the complex intertextual relationships with regards to Keats’s poetry and biography show the way Simmons expresses humanism as a belief in man’s dignity and worth, and uses it as the basis for his epic narrative. Keywords: Dan Simmons; The Hyperion Cantos; John Keats’s poetry and letters; intertextuality; empathy; beauty; love; humanism. Gräslund 2 The American author Dan Simmons is a prolific writer who has published in different genres. -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

TITLE AUTHOR SUBJECTS Adult Fiction Book Discussion Kits

Adult Fiction Book Discussion Kits Book Discussion Kits are designed for book clubs and other groups to read and discuss the same book. The kits include multiple copies of the book and a discussion guide. Some kits include Large Print copies (noted below in the subject area). Additional Large Print, CDbooks or DVDs may be added upon request, if available. The kit is checked out to one group member who is responsible for all the materials. Book Discussion Kits can be reserved in advance by calling the Adult Services Department, 314-994-3300 ext 2030. Kits may be picked up at any SLCL location, and should be returned inside the branch during normal business hours. To check out a kit, you’ll need a valid SLCL card. Kits are checked out for up to 8 weeks, and may not be renewed. Up to two kits may be checked out at one time to an individual. Customers will not receive a phone call or email when the kit is ready for pick up, so please note the pickup date requested. To search within this list when viewing it on a computer, press the Ctrl and F keys simultaneously, then type your search term (author, title, or subject) into the search box and press Enter. Use the arrow keys next to the search box to navigate to the matches. For a full plot summary, please click on the title, which links to the library catalog. New Book Discussion Kits are in bold red font, updated 11/19. TITLE AUTHOR SUBJECTS 1984 George Orwell science fiction/dystopias/totalitarianism Accident Chris Pavone suspense/spies/assassins/publishing/manuscripts/Large Print historical/women -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature

From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Dorian Townsend Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Languages and Linguistics Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of New South Wales May 2011 PLEASE TYPE THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname or Family name: Townsend First name: Dorian Other name/s: Aleksandra PhD, Russian Studies Abbreviation for degree as given in the University calendar: School: Languages and Linguistics Faculty: Arts and Social Sciences Title: From Upyr’ to Vampir: The Slavic Vampire Myth in Russian Literature Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) The Slavic vampire myth traces back to pre-Orthodox folk belief, serving both as an explanation of death and as the physical embodiment of the tragedies exacted on the community. The symbol’s broad ability to personify tragic events created a versatile system of imagery that transcended its folkloric derivations into the realm of Russian literature, becoming a constant literary device from eighteenth century to post-Soviet fiction. The vampire’s literary usage arose during and after the reign of Catherine the Great and continued into each politically turbulent time that followed. The authors examined in this thesis, Afanasiev, Gogol, Bulgakov, and Lukyanenko, each depicted the issues and internal turmoil experienced in Russia during their respective times. By employing the common mythos of the vampire, the issues suggested within the literature are presented indirectly to the readers giving literary life to pressing societal dilemmas. The purpose of this thesis is to ascertain the vampire’s function within Russian literary societal criticism by first identifying the shifts in imagery in the selected Russian vampiric works, then examining how the shifts relate to the societal changes of the different time periods. -

Award Winners

RITA Awards (Romance) Silent in the Grave / Deanna Ray- bourn (2008) Award Tribute / Nora Roberts (2009) The Lost Recipe for Happiness / Barbara O'Neal (2010) Winners Welcome to Harmony / Jodi Thomas (2011) How to Bake a Perfect Life / Barbara O'Neal (2012) The Haunting of Maddy Clare / Simone St. James (2013) Look for the Award Winner la- bel when browsing! Oshkosh Public Library 106 Washington Ave. Oshkosh, WI 54901 Phone: 920.236.5205 E-mail: Nothing listed here sound inter- [email protected] Here are some reading suggestions to esting? help you complete the “Award Winner” square on your Summer Reading Bingo Ask the Reference Staff for card! even more awards and winners! 2016 National Book Award (Literary) The Fifth Season / NK Jemisin Pulitzer Prize (Literary) Fiction (2016) Fiction The Echo Maker / Richard Powers (2006) Gilead / Marilynn Robinson (2005) Tree of Smoke / Dennis Johnson (2007) Agatha Awards (Mystery) March /Geraldine Brooks (2006) Shadow Country / Peter Matthiessen (2008) The Virgin of Small Plains /Nancy The Road /Cormac McCarthy (2007) Let the Great World Spin / Colum McCann Pickard (2006) The Brief and Wonderous Life of Os- (2009) A Fatal Grace /Louise Penny car Wao /Junot Diaz (2008) Lord of Misrule / Jaimy Gordon (2010) (2007) Olive Kitteridge / Elizabeth Strout Salvage the Bones / Jesmyn Ward (2011) The Cruelest Month /Louise Penny (2009) The Round House / Louise Erdrich (2012) (2008) Tinker / Paul Harding (2010) The Good Lord Bird / James McBride (2013) A Brutal Telling /Louise Penny A Visit -

Connie Willis, June 2019

Science Fiction Book Club Interview with Connie Willis, June 2019 Connie Willis has won eleven Hugo Awards and seven Nebula Awards more major awards than any other writer—most recently the "Best Novel" Hugo and Nebula Awards for Blackout/All Clear (2010). She was inducted by the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2009 and the Science Fiction Writers of America named her its 28th SFWA Grand Master in 2011. Wow! So many questions! I’m not sure I can answer all of them, but here goes. 1. Why writing? I don’t think any writer has a good answer for this. You don’t pick it--it picks you. I’ve loved books since I first discovered them--the first one I remember began, "There’s a cat in a hat in a ball in the hall," and I instantly knew, like Rudyard Kipling, that books held in them everything that would make me happy. When I learned to read, I saw that this was true, and I gobbled up LITTLE WOMEN and Gene Stratton Porter’s A GIRL OF THE LIMBERLOST and L. Frank Baum’s WIZARD OF OZ books and everything else I could get my hands on, which mostly meant the books at the public library, though the girl across the street loaned me Frances Hodgson Burnett’s A LITTLE PRINCESS and my great aunt left me Grace Livingston Hill’s THE WHITE FLOWER and one of my mother’s friends loaned me Valentine Davies’ A MIRACLE ON THIRTY-FOURTH STREET. Many of the books I read were had writers as characters--Jo March and Anne of Green Gables and Betsy of the BETSY, TACY, AND TIB books--and I wanted to be exactly like them, which to me meant not only writing books, but wearing long dresses, sitting in a garret reading and eating russet apples, and tying my hand-written manuscripts up with red ribbons.