Lightspeed Magazine, Issue 78 (November 2016)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Statistics Document

MidAmeriCon II 2016 Hugo Award Statistics Page 1 of 27 2016 Final Results for Best Novel 3,130 valid ballots cast. 25% cutoff = 753 voters. 2,903 valid votes cast in category. Race for position 1 Finalist Pass 1 Pass 2 Pass 3 Pass 4 Pass 5 Runoff Fifth Season 969 973 997 1208 1372 2073 Uprooted 722 725 801 944 1203 Seveneves: A Novel 431 432 517 609 Ancillary Mercy 475 476 507 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 256 261 No Award 50 429 Preference 2903 2867 2822 2761 2575 2502 No Preference 0 36 81 142 328 401 Total Votes 2903 2903 2903 2903 2903 2903 Race for Position 2 Race for Position 3 Finalist Pass 1 Pass 2 Pass 3 Pass 4 Finalist Pass 1 Uprooted 1152 1157 1251 1521 Ancillary Mercy 1443 Ancillary Mercy 843 849 892 1102 Seveneves: A Novel 856 Seveneves: A Novel 520 523 621 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's 399 Cinder Spires: The Windlass 280 285 Aeronaut's Windlass No Award 107 No Award 78 Preference 2805 Preference 2873 2814 2764 2623 No Preference 98 No Preference 30 89 139 280 Total Votes 2903 Total Votes 2903 2903 2903 2903 Race for Position 4 Race for Position 5 Finalist Pass 1 Finalist Pass 1 Seveneves: A Novel 1500 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 1409 Cinder Spires: The Aeronaut's Windlass 619 No Award 902 No Award 480 Preference 2311 Preference 2599 No Preference 592 No Preference 304 Total Votes 2903 Total Votes 2903 MidAmeriCon II 2016 Hugo Award Statistics Page 2 of 27 2016 Final Results for Best Novella 3,130 valid ballots cast. -

Searching for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

THE FRONTIERS COLLEctION THE FRONTIERS COLLEctION Series Editors: A.C. Elitzur L. Mersini-Houghton M. Schlosshauer M.P. Silverman J. Tuszynski R. Vaas H.D. Zeh The books in this collection are devoted to challenging and open problems at the forefront of modern science, including related philosophical debates. In contrast to typical research monographs, however, they strive to present their topics in a manner accessible also to scientifically literate non-specialists wishing to gain insight into the deeper implications and fascinating questions involved. Taken as a whole, the series reflects the need for a fundamental and interdisciplinary approach to modern science. Furthermore, it is intended to encourage active scientists in all areas to ponder over important and perhaps controversial issues beyond their own speciality. Extending from quantum physics and relativity to entropy, consciousness and complex systems – the Frontiers Collection will inspire readers to push back the frontiers of their own knowledge. Other Recent Titles Weak Links Stabilizers of Complex Systems from Proteins to Social Networks By P. Csermely The Biological Evolution of Religious Mind and Behaviour Edited by E. Voland and W. Schiefenhövel Particle Metaphysics A Critical Account of Subatomic Reality By B. Falkenburg The Physical Basis of the Direction of Time By H.D. Zeh Mindful Universe Quantum Mechanics and the Participating Observer By H. Stapp Decoherence and the Quantum-To-Classical Transition By M. Schlosshauer The Nonlinear Universe Chaos, Emergence, Life By A. Scott Symmetry Rules How Science and Nature are Founded on Symmetry By J. Rosen Quantum Superposition Counterintuitive Consequences of Coherence, Entanglement, and Interference By M.P. -

50% Off List Copy

! ! ! ! ! ! James M. Dourgarian, Bookman! 1595-B Third Avenue! Walnut Creek, CA 94597! (925) 935-5033! [email protected]" www.jimbooks.com! ! Any item is returnable for any reason with seven days of receipt, if prior notice is given, and! if the same item is returned in the same condition as sent.! !Purchases by California resident are subject to 8.5% sales tax.! !Postage is $4 for the first item and $1 each thereafter.! Payment in U. S. dollars only. Visa, MasterCard, Discover, and American Express accepted.! ! Items are offered at a 50% discount on the prices shown. No other discounts apply. This discount applies only to direct orders. It does not apply to orders via ABE, Biblio, the! ABAA website, or my own website, which I would encourage you to visit.! 1. Algren, Nelson. Walk On The Wild Side. Columbia, 1962, first edition thus, self- wrappers. Softcover. An original-release film pressbook, 12 pages, with advertising supplement laid in. Fine. JD5 $10.00.! 2. Allen, Woody. Side Effects. NY, Random House, 1980, first edition, dust jacket. Hardcover. Very fine. JD17 $25.00.! 3. Allison, Dorothy. Two Or Three Things I Know For Sure. NY, Dutton, August 1995, first edition, dust jacket. Hardcover. Inscribed by author to the Jack London Foundation for use in an auction fund-raiser. Very fine, unread. JD31 $30.00.! 4. Benson, Jackson J. Wallace Stegner His Life And Work. NY, Viking, 1996, first edition, slick photographic wrappers. Softcover. Advance copy, an uncorrected proof of this long-awaited biography, this was the biographer's own personal copy, so Signed by Benson. -

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk

Mirrorshade Women: Feminism and Cyberpunk at the Turn of the Twenty-first Century Carlen Lavigne McGill University, Montréal Department of Art History and Communication Studies February 2008 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Communication Studies © Carlen Lavigne 2008 2 Abstract This study analyzes works of cyberpunk literature written between 1981 and 2005, and positions women’s cyberpunk as part of a larger cultural discussion of feminist issues. It traces the origins of the genre, reviews critical reactions, and subsequently outlines the ways in which women’s cyberpunk altered genre conventions in order to advance specifically feminist points of view. Novels are examined within their historical contexts; their content is compared to broader trends and controversies within contemporary feminism, and their themes are revealed to be visible reflections of feminist discourse at the end of the twentieth century. The study will ultimately make a case for the treatment of feminist cyberpunk as a unique vehicle for the examination of contemporary women’s issues, and for the analysis of feminist science fiction as a complex source of political ideas. Cette étude fait l’analyse d’ouvrages de littérature cyberpunk écrits entre 1981 et 2005, et situe la littérature féminine cyberpunk dans le contexte d’une discussion culturelle plus vaste des questions féministes. Elle établit les origines du genre, analyse les réactions culturelles et, par la suite, donne un aperçu des différentes manières dont la littérature féminine cyberpunk a transformé les usages du genre afin de promouvoir en particulier le point de vue féministe. -

Auroran Lights

AURORAN LIGHTS The Official E-zine of the Canadian Science Fiction & Fantasy Association Dedicated to Promoting the Prix Aurora Awards and the Canadian SF&F Genre (Issue # 14 –December/January 2014/2015) 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 – EDITORIAL CSFFA SECTION 04 – 2015 Aurora Award Eligibility List open. 04 – 2015 Aurora Award Nominations open. 04 – CSFFA AGM. 04 – 2015 Aurora Award Voting start date. PRODOM SECTION 05 – MILESTONES – Matthew Hughes & Jack Vance 05 – AWARDS – Sunburst Awards, Rhysling Poetry Awards. 09 – CONTESTS – Friends of the Merril Short Story Contest, Roswell Short Story Contest, Subterrain Magazine Fiction, Poetry & Non-Fiction Contest, Pulp Literature Magazine Swallows Sequential Graphic Arts Short Story Contest. 15 – EVENTS – ChiZine readings – Christi Charish & Jennifer Lott 10 – POETS & POEMS – Brains, Brains, Brains by Puneet Dutt, A Portrait of the Monster as an Artist by Dominik Parisien, 16 – PRO DOINGS – Condolences to Spider Robinson and how you can help him. 16 – CURRENT BOOKS – To Make a Witch by Heather Hamilton-Senter, Titanium Black by Michael J. Lee, An Inconvenient Corpse by Jason E. Rolfe, The Scrambled Man by Michael J. Bertrand, 17 – UPCOMING BOOKS & STORIES – The Occasional Diamond Thief by J.A. McLachlan, When Things Go Wobbly by Gregg Chamberlain, Ten Little Zombies by Gregg Chamberlain, Mirrors Heart by Justine Alley Dowsett and Murandy Damodred, 20 – MAGAZINES – Apex Magazine, Uncanny Magazine, Canadian Science Fiction Review, Sci Phi Journal, Galaxy’s Edge Magazine. 27 – MARKETS – Ideomancer Magazine, Uncanny Magazine, Canadian Science Fiction Review, Bundoran Press, SCIFI Journal, Clockwork Anthology, Mythic Derlium Magazine, Tartarus Press, Terraform Online Magazine, Third Person Press, Mirror World Publishing. -

TITLE AUTHOR SUBJECTS Adult Fiction Book Discussion Kits

Adult Fiction Book Discussion Kits Book Discussion Kits are designed for book clubs and other groups to read and discuss the same book. The kits include multiple copies of the book and a discussion guide. Some kits include Large Print copies (noted below in the subject area). Additional Large Print, CDbooks or DVDs may be added upon request, if available. The kit is checked out to one group member who is responsible for all the materials. Book Discussion Kits can be reserved in advance by calling the Adult Services Department, 314-994-3300 ext 2030. Kits may be picked up at any SLCL location, and should be returned inside the branch during normal business hours. To check out a kit, you’ll need a valid SLCL card. Kits are checked out for up to 8 weeks, and may not be renewed. Up to two kits may be checked out at one time to an individual. Customers will not receive a phone call or email when the kit is ready for pick up, so please note the pickup date requested. To search within this list when viewing it on a computer, press the Ctrl and F keys simultaneously, then type your search term (author, title, or subject) into the search box and press Enter. Use the arrow keys next to the search box to navigate to the matches. For a full plot summary, please click on the title, which links to the library catalog. New Book Discussion Kits are in bold red font, updated 11/19. TITLE AUTHOR SUBJECTS 1984 George Orwell science fiction/dystopias/totalitarianism Accident Chris Pavone suspense/spies/assassins/publishing/manuscripts/Large Print historical/women -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction

Andrew May Pseudoscience and Science Fiction Science and Fiction Editorial Board Mark Alpert Philip Ball Gregory Benford Michael Brotherton Victor Callaghan Amnon H Eden Nick Kanas Geoffrey Landis Rudi Rucker Dirk Schulze-Makuch Ru€diger Vaas Ulrich Walter Stephen Webb Science and Fiction – A Springer Series This collection of entertaining and thought-provoking books will appeal equally to science buffs, scientists and science-fiction fans. It was born out of the recognition that scientific discovery and the creation of plausible fictional scenarios are often two sides of the same coin. Each relies on an understanding of the way the world works, coupled with the imaginative ability to invent new or alternative explanations—and even other worlds. Authored by practicing scientists as well as writers of hard science fiction, these books explore and exploit the borderlands between accepted science and its fictional counterpart. Uncovering mutual influences, promoting fruitful interaction, narrating and analyzing fictional scenarios, together they serve as a reaction vessel for inspired new ideas in science, technology, and beyond. Whether fiction, fact, or forever undecidable: the Springer Series “Science and Fiction” intends to go where no one has gone before! Its largely non-technical books take several different approaches. Journey with their authors as they • Indulge in science speculation—describing intriguing, plausible yet unproven ideas; • Exploit science fiction for educational purposes and as a means of promoting critical thinking; • Explore the interplay of science and science fiction—throughout the history of the genre and looking ahead; • Delve into related topics including, but not limited to: science as a creative process, the limits of science, interplay of literature and knowledge; • Tell fictional short stories built around well-defined scientific ideas, with a supplement summarizing the science underlying the plot. -

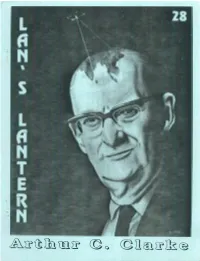

Lan's Lantern 28

it th Si th ir ©o Lmis £antmi 2 8 An Arthur £. £(ar£c Special Table of Contents Arthur C. Clarke................................................... by Bill Ware..Front Cover Tables of contents, artists, colophon,......................................................... 1 Arthur C. Clarke...............................................................Lan.......................................2 I Don’t Understand What’s Happening Here...John Purcell............... 3 Arthur C. Clarke: The Prophet Vindicated...Gregory Benford....4 Of Sarongs & Science Fiction: A Tribute to Arthur C. Clarke Ben P. Indick............... 6 An Arthur C. Clarke Chronology.......................... Robert Sabella............. 8 Table of Artists A Childhood's End Remembrance.............................Gary Lovisi.................... 9 My Hero.................................................................................. Mary Lou Lockhart..11 Paul Anderegg — 34 A Childhood Well Wasted: Some Thoughts on Arthur C. Clarke Sheryl Birkhead — 2 Andrew Hooper.............12 PL Caruthers-Montgomery Reflections on the Style of Arthur C. Clarke and, to a Lesser — (Calligraphy) 1, Degree, a Review of 2061: Odyssey Three...Bill Ware.......... 17 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, About the Cover...............................................................Bill Ware.......................17 12, 17, 18, 19, 20, My Childhood’s End....................................................... Kathy Mar.......................18 21, 22, 24, 28, 31 Childhood’s End.......................Words & Music -

Nightmare Magazine, Issue 43 (April 2016)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 43, April 2016 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, April 2016 FICTION Reaper’s Rose Ian Whates Death’s Door Café Kaaron Warren The Girl Who Escaped From Hell Rahul Kanakia The Grave P.D. Cacek NONFICTION The H Word: The Monstrous Intimacy of Poetry in Horror Evan J. Peterson Artist Showcase: Yana Moskaluk Marina J. Lostetter Interview: David J. Schow Lisa Morton AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Ian Whates Kaaron Warren Rahul Kanakia P.D. Cacek MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks About the Nightmare Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2016 Nightmare Magazine Cover by Yana Moskaluk www.nightmare-magazine.com FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, April 2016 John Joseph Adams | 750 words Welcome to issue forty-three of Nightmare! This month, we have original fiction from Ian Whates (“Reaper’s Rose”) and Rahul Kanakia (“The Girl Who Escaped From Hell”), along with reprints by Kaaron Warren (“Death’s Door Cafe”) and P.D. Cacek (“The Grave”). We also have the latest installment of our column on horror, “The H Word,” plus author spotlights with our authors, a showcase on our cover artist, and a feature interview with author David J. Schow. Nebula Award Nominations ICYMI last month, awards season is officially upon us, and it looks like 2015 was a terrific year for our publications. The first of the major awards have announced their lists of finalists for last year’s work, and we’re pleased to announce that “Hungry Daughters of Starving Mothers” by Alyssa Wong (Nightmare, Oct. 2015) is a finalist for the Nebula Award this year! Over at Lightspeed, “Madeleine” by Amal El-Mohtar (Lightspeed, June 2015) and “And You Shall Know Her by the Trail of Dead” by Brooke Bolander (Lightspeed, Feb. -

Forbidden Planet” (1956): Origins in Pulp Science Fiction

“Forbidden Planet” (1956): Origins in Pulp Science Fiction By Dr. John L. Flynn While most critics tend to regard “Forbidden Planet” (1956) as a futuristic retelling of William Shakespeare’s “The Tempest”—with Morbius as Prospero, Robby the Robot as Arial, and the Id monster as the evil Caliban—this very conventional approach overlooks the most obvious. “Forbidden Planet” was, in fact, pulp science fiction, a conglomeration of every cliché and melodramatic element from the pulp magazines of the 1930s and 1940s. With its mysterious setting on an alien world, its stalwart captain and blaster-toting crew, its mad scientist and his naïve yet beautiful daughter, its indispensable robot, and its invisible monster, the movie relied on a proven formula. But even though director Fred Wilcox and scenarist Cyril Hume created it on a production line to compete with the other films of its day, “Forbidden Planet” managed to transcend its pulp origins to become something truly memorable. Today, it is regarded as one of the best films of the Fifties, and is a wonderful counterpoint to Robert Wise’s “The Day the Earth Stood Still”(1951). The Golden Age of Science Fiction is generally recognized as a twenty-year period between 1926 and 1946 when a handful of writers, including Clifford Simak, Jack Williamson, Isaac Asimov, John W. Campbell, Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Frederick Pohl, and L. Ron Hubbard, were publishing highly original, science fiction stories in pulp magazines. While the form of the first pulp magazine actually dates back to 1896, when Frank A. Munsey created The Argosy, it wasn’t until 1926 when Hugo Gernsback published the first issue of Amazing Stories that science fiction had its very own forum. -

What You Left Behind

A SHORT STORY BY ALYSSA WONG STORY ALYSSA WONG Illustrations Arnold Tsang Baptiste Medic Model Nathan Brock Baptiste Original Model Hong-Chan Lim Baptiste Original Concept Ben Zhang Layout & Design Benjamin Scanlon What You Left Behind “Take a deep breath for me, auntie,” Baptiste said. Madame Thebeau, in her early seventies and sharp as a needle, sat on the exam table, her feet hanging over the side in their plastic slippers. Baptiste listened to her breathing through the stethoscope pressed to her back. “All right, that’s good.” “Did you find anything interesting, young man?” she said, stretching. When she met his gaze, she winked. “Nothing unusual. Everything sounds like it’s working properly.” Baptiste folded the stethoscope and held out his hand to help her down from the table. He was dressed for the clinic today, wearing all white scrubs. “You’ll get your labs back in a week or two. Dr. Mondésir will call you when they’re in. Or should I ask her to call your nephew to let him know?” “I have a cell phone. She can call me directly.” Madame Thebeau stretched, her colorful bangles clattering around her wrists. She took Baptiste’s hand and eased her way off the exam table and onto the linoleum floor. “So can you, for that matter. But I don’t seem to have your number.” Baptiste led her out of the exam room and back into the hallway. “Well, unfortunately, I’m leaving town very soon, so I won’t be able to handle your follow-up care.