Using Local Hunters' Knowledge to Conserve Elusive Species in Vietnam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/07/2021 06:11:13PM Via Free Access

Tijdschrift voor Entomologie 160 (2017) 89–138 An initial survey of aquatic and semi-aquatic Heteroptera (Insecta) from the Cardamom Mountains and adjacent uplands of southwestern Cambodia, with descriptions of four new species Dan A. Polhemus Previous collections of aquatic Heteroptera from Cambodia have been limited, and the biota of the country has remained essentially undocumented until the past several years. Recent surveys of aquatic Heteroptera in the Cardamom Mountains and adjacent Kirirom and Bokor plateaus of southwestern Cambodia, coupled with previous literature records, demonstrate that 11 families, 35 genera, and 68 species of water bugs occur in this area. These collections include 13 genus records and 37 species records newly listed for the country of Cambodia. The following four new species are described based on these recent surveys: Amemboa cambodiana n. sp. (Gerridae); Microvelia penglyi n. sp., Microvelia setifera n. sp. and Microvelia bokor n. sp. (all Veliidae). Based on an updated checklist provided herein, the aquatic Heteroptera biota of Cambodia as currently known consists of 78 species, and has an endemism rate of 7.7%, although these numbers should be considered provisional pending further sampling. Keywords: Heteroptera; Cambodia; water bugs; new species; new records Dan A. Polhemus, Department of Natural Sciences, Bishop Museum, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, HI 96817 USA. [email protected] Introduction of collections or species records from the country in Aquatic and semi-aquatic Heteroptera, commonly the period preceding World War II. Following that known as water bugs, are a group of worldwide dis- war, the country’s traumatic social and political his- tribution with a well-developed base of taxonomy. -

Chapter 6 South-East Asia

Chapter 6 South-East Asia South-East Asia is the least compact among the extremity of North-East Asia. The contiguous ar- regions of the Asian continent. Out of its total eas constituting the continental interior include land surface, estimated at four million sq.km., the the highlands of Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and mainland mass has a share of only 40 per cent. northern Vietnam. The relief pattern is that of a The rest is accounted for by several thousand is- longitudinal ridge and furrow in Myanmar and lands of the Indonesian and Philippine archipela- an undulating plateau eastwards. These are re- goes. Thus, it is composed basically of insular lated to their structural difference: the former and continental components. Nevertheless the being a zone of tertiary folds and the latter of orographic features on both these landforms are block-faulted massifs of greater antiquity. interrelated. This is due to the focal location of the region where the two great axes, one of lati- The basin of the Irrawady (Elephant River), tudinal Cretaceo-Tertiary folding and the other forming the heartland of Myanmar, is ringed by of the longitudinal circum-Pacific series, converge. mountains on three sides. The western rampart, This interface has given a distinctive alignment linking Patkai, Chin, and Arakan, has been dealt to the major relief of the region as a whole. In with in the South Asian context. The northern brief, the basic geological structures that deter- ramparts, Kumon, Kachin, and Namkiu of the mine the trend of the mountains are (a) north- Tertiary fold, all trend north-south parallel to the south and north-east in the mainland interior, (b) Hengduan Range and are the highest in South- east-west along the Indonesian islands, and (c) East Asia; and this includes Hkakabo Raz north-south across the Philippines. -

Panthera Pardus) Range Countries

Profiles for Leopard (Panthera pardus) Range Countries Supplemental Document 1 to Jacobson et al. 2016 Profiles for Leopard Range Countries TABLE OF CONTENTS African Leopard (Panthera pardus pardus)...................................................... 4 North Africa .................................................................................................. 5 West Africa ................................................................................................... 6 Central Africa ............................................................................................. 15 East Africa .................................................................................................. 20 Southern Africa ........................................................................................... 26 Arabian Leopard (P. p. nimr) ......................................................................... 36 Persian Leopard (P. p. saxicolor) ................................................................... 42 Indian Leopard (P. p. fusca) ........................................................................... 53 Sri Lankan Leopard (P. p. kotiya) ................................................................... 58 Indochinese Leopard (P. p. delacouri) .......................................................... 60 North Chinese Leopard (P. p. japonensis) ..................................................... 65 Amur Leopard (P. p. orientalis) ..................................................................... 67 Javan Leopard -

Southern Cardamom Forest Protection Cambodia

Southern Cardamom Forest Protection Koh Kong Province Cambodia Defending one of the last unfragmented rainforests in Southeast Asia The Southern Cardamom project protects a mosaic of habitats from dense evergreen and pine forests to wetlands, flooded grasslands, lakes and coastal mangroves. As well as covering parts of the Southern Cardamom National Park and Tatai Wildlife Sanctuary the project also protects a critical part of the Cardamom Mountains Rainforest Ecoregion – one of the most important locations for biodiversity conservation on the planet. This unique project is home to at least 52 IUCN threatened species of mammals, birds and reptiles: Siamese crocodiles, sunbears, clouded leopards and one of Cambodia’s two populations of Asian elephants. southpole.com/projects Project 302 724 | 1768EN, 04.2020 The Context Thanks to the creation The diverse ecosystems protected by the project are some of the most important of a scholarship fund, biodiversity hotspots on the planet; however, they are also one of the most endangered. children from the local rural Deforestation and forest degradation is driven by illegal logging and clearing forest to communities are able to make way for agricultural land and plantations, as well as fuel collection and charcoal continue their education production. Largely due to a lack of alternative opportunities, many local residents rely on small-scale farming for their livelihood. after primary school The Project Covering over 445,000 ha in western Cambodia, the Southern Cardamom project aims to address these local drivers of deforestation. The project offers training on improved farming techniques so farmers can increase yields on smaller plots of land; and also develops community-based ecotourism, increasing the economic value of keeping the forest standing. -

Developing Partnerships for Conservation in the Cardamom Mountains, Cambodia

Volume 10: Protected Areas and Sustainable Tourism 53 Developing Partnerships for Conservation in the Cardamom Mountains, Cambodia P. Dearden1, S. Gauntlet2 and B. Nollen3 1University of Victoria, Victoria, Canada 2Wildlife Alliance, Phnom Penh, Cambodia 3 International Consultancy Europe, Bangkok, Thailand Abstract Protected areas owned and operated by national agencies have long been the mainstay of global conservation planning. However much more needs to be done to conserve the biodiversity of the broader landscape than can be achieved solely within the confines of protected area systems run by national governments. This paper describes an initiative in the Cardamom Mountains, Cambodia, where conservation planning embraces a large number of stakeholders using a variety of approaches to achieve conservation goals. The Cardamom Mountains cover some 880 000 ha of seasonal rainforest in SW Cambodia and are thought to be the largest contiguous extent of this forest formation remaining in mainland SE Asia. Many species, such as elephants, tigers, banteng and dhole that are regionally rare can still be found in the forests. The area is also home to the world’s largest population of Siamese crocodiles and various other critically endangered species, especially turtles. The area is coming under increasing pressure from both legal and illegal activities and conservation groups have been pro- active in designing and implementing a variety of approaches that accept the needs for economic development, but strive to achieve this in a sustainable manner. In the South West Cardamoms Wildlife Alliance, a US-based NGO has partnered with the private sector to access funds that allow such plans to be implemented in a manner consistent with government policy. -

Thailands Beaches and Islands

EYEWITNESS TRAVEL THAILAND’S BEACHES & ISLANDS BEACHES • WATER SPORTS RAINFORESTS • TEMPLES FESTIVALS • WILDLIFE SCUBA DIVING • NATIONAL PARKS MARKETS • RESTAURANTS • HOTELS THE GUIDES THAT SHOW YOU WHAT OTHERS ONLY TELL YOU EYEWITNESS TRAVEL THAILAND’S BEACHES AND ISLANDS EYEWITNESS TRAVEL THAILAND’S BEACHES AND ISLANDS MANAGING EDITOR Aruna Ghose SENIOR EDITORIAL MANAGER Savitha Kumar SENIOR DESIGN MANAGER Priyanka Thakur PROJECT DESIGNER Amisha Gupta EDITORS Smita Khanna Bajaj, Diya Kohli DESIGNER Shruti Bahl SENIOR CARTOGRAPHER Suresh Kumar Longtail tour boats at idyllic Hat CARTOGRAPHER Jasneet Arora Tham Phra Nang, Krabi DTP DESIGNERS Azeem Siddique, Rakesh Pal SENIOR PICTURE RESEARCH COORDINATOR Taiyaba Khatoon PICTURE RESEARCHER Sumita Khatwani CONTRIBUTORS Andrew Forbes, David Henley, Peter Holmshaw CONTENTS PHOTOGRAPHER David Henley HOW TO USE THIS ILLUSTRATORS Surat Kumar Mantoo, Arun Pottirayil GUIDE 6 Reproduced in Singapore by Colourscan Printed and bound by L. Rex Printing Company Limited, China First American Edition, 2010 INTRODUCING 10 11 12 13 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 THAILAND’S Published in the United States by Dorling Kindersley Publishing, Inc., BEACHES AND 375 Hudson Street, New York 10014 ISLANDS Copyright © 2010, Dorling Kindersley Limited, London A Penguin Company DISCOVERING ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNDER INTERNATIONAL AND PAN-AMERICAN COPYRIGHT CONVENTIONS. NO PART OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE REPRODUCED, STORED IN THAILAND’S BEACHES A RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, AND ISLANDS 10 ELECTRONIC, MECHANICAL, PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING OR OTHERWISE WITHOUT THE PRIOR WRITTEN PERMISSION OF THE COPYRIGHT OWNER. Published in Great Britain by Dorling Kindersley Limited. PUTTING THAILAND’S A CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION RECORD IS BEACHES AND ISLANDS AVAILABLE FROM THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS. -

Phylogenetics, Biogeography, and Patterns of Diversification Of

Brigham Young University Masthead Logo BYU ScholarsArchive All Theses and Dissertations 2017-04-01 Phylogenetics, Biogeography, and Patterns of Diversification of GeckosAcross the Sunda Shelf with an Emphasis on the GenusCnemaspis (Strauch, 1887) Perry Lee Wood Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Wood, Perry Lee, "Phylogenetics, Biogeography, and Patterns of Diversification of GeckosAcross the Sunda Shelf with an Emphasis on the GenusCnemaspis (Strauch, 1887)" (2017). All Theses and Dissertations. 7259. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/7259 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Phylogenetics,Biogeography,andPatternsofDiversificationofGeckos AcrosstheSundaShelfwithanEmphasisontheGenus Cnemaspis(Strauch,1887) PerryLeeWood Jr. Adissertationsubmittedtothefacultyof BrighamYoungUniversity inpartialfulfillmentoftherequirementsforthedegreeof DoctorofPhilosophy JackW.Sites Jr.,Chair ByronJ.Adams SethM.Bybee L.LeeGrismer DukeS.Rogers DepartmentofBiology BrighamYoungUniversity Copyright©2017PerryLeeWood Jr. AllRightsReserved ABSTRACT Phylogenetics,Biogeography,andPatternsofDiversificationofGeckos AcrosstheSundaShelfwithanEmphasisontheGenus Cnemaspis(Strauch,1887) PerryLeeWood Jr. DepartmentofBiology,BYU -

Disaster Management Partners in Thailand

Cover image: “Thailand-3570B - Money flows like water..” by Dennis Jarvis is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 https://www.flickr.com/photos/archer10/3696750357/in/set-72157620096094807 2 Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance Table of Contents Welcome - Note from the Director 8 About the Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance 9 Disaster Management Reference Handbook Series Overview 10 Executive Summary 11 Country Overview 14 Culture 14 Demographics 15 Ethnic Makeup 15 Key Population Centers 17 Vulnerable Groups 18 Economics 20 Environment 21 Borders 21 Geography 21 Climate 23 Disaster Overview 28 Hazards 28 Natural 29 Infectious Disease 33 Endemic Conditions 33 Thailand Disaster Management Reference Handbook | 2015 3 Government Structure for Disaster Management 36 National 36 Laws, Policies, and Plans on Disaster Management 43 Government Capacity and Capability 51 Education Programs 52 Disaster Management Communications 54 Early Warning System 55 Military Role in Disaster Relief 57 Foreign Military Assistance 60 Foreign Assistance and International Partners 60 Foreign Assistance Logistics 61 Infrastructure 68 Airports 68 Seaports 71 Land Routes 72 Roads 72 Bridges 74 Railways 75 Schools 77 Communications 77 Utilities 77 Power 77 Water and Sanitation 80 4 Center for Excellence in Disaster Management & Humanitarian Assistance Health 84 Overview 84 Structure 85 Legal 86 Health system 86 Public Healthcare 87 Private Healthcare 87 Disaster Preparedness and Response 87 Hospitals 88 Challenges -

Mekong River Commission Secretariat Environmental Program

Mekong River Commission Secretariat Environmental Program (Final Draft) A Review of Biological Assessment of Freshwater Ecosystems A Collaborative Work By: Srum Lim Song Neou Bonheur Uy Ching Date of Submission: 02 January 2002 MRC, January 2002 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………… 3 2. Purpose and Methodology………………………………………………… 4 2.1. Principles and Methods …………………………………………………… 4 2.2. Objectives and Methods of This Paper …..………………………………… 5 3. Institutional Arrangement For Biological Assessment ……………….…… 5 3.1. Ministry of Environment……………………………………………….……. 5 3.2. Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries………………………..……. 6 3.2.1. Department of Fisheries ………………………………………………… 6 3.2.2. Department of Forestry ………………………………………………… 7 3.2.3. Department of Agronomy ……………………………………………… 7 3.3. Ministry of land Management, Urbanization and Construction………..…… 7 3.4. Ministry of Water Resources and Meteorology……………………………… 7 3.5. Cambodian National Mekong Committee…………………………………… 8 3.6. Mekong River Commission Secretariat …………………………………….. 8 4. Biodiversity Status……………………………………………………..……. 8 4.1. Ecosystem Diversity………………………………………………………… 9 4.2. Species Diversity……………………………………………………………. 11 4.2.1 Flooded Forest…………………………………………………………… 11 4.2.2 Fish……………………………………………………………………… 12 4.2.3 Waterbirds……………………………………………………………… 13 4.2.4 Mammal ……………………………………………………………… 14 4.2.5 Reptiles………………………………………………………………… 14 4.2.6 Invertebrate ……………………………………………………………. 15 4.3. Genetic Diversity…………………………………………………………… 16 5. Biological Use………………………………………………………………. -

BIODIVERSITY and PROTECTED AREAS Viet Nam

Page 1 of 21 Regional Environmental Technical Assistance 5771 Poverty Reduction & Environmental Management in Remote Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) Watersheds Project (Phase I) BIODIVERSITY AND PROTECTED AREAS Viet Nam By J E Clarke, PhD CONTENTS 1 BACKGROUND 3 1.1 Country profile 3 1.2 Biodiversity 4 2 BIODIVERSITY POLICY 13 3 BIODIVERSITY LEGISLATION 15 3.1 State law 15 3.2 International conventions 16 4 CATEGORIES OF PROTECTED AREAS 16 5 INSTITUTIONAL ARRANGEMENTS 17 5.1 State management 17 5.2 NGO and donor involvement 18 5.3 Private sector involvement 19 6 INVENTORY OF PROTECTED AREAS 20 7 CONSERVATION COVERAGE BY PROTECTED AREAS 23 8 AREAS OF MAJOR BIODIVERSITY SIGNIFICANCE 24 9 TOURISM IN PROTECTED AREAS 25 10 COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION 26 11 GENDER 26 12 CROSS BOUNDARY ISSUES 27 12.1 Internal boundaries 27 Page 2 of 21 12.2 International borders 27 12.3 Cross border trade 28 13 MAJOR PROBLEMS AND ISSUES 29 1. BACKGROUND 1.1 Country profile Viet Nam occupies a narrow sinusoid band of country along the east coast of Indochina, between latitudes 8º30' and 23º25' N, and longitudes 102º10' and 109º25'. Its total area is 332,000 km 2. Most of the country is hilly or mountainous. Elevations range from sea level to over 3,000 metres on the Hoang Lien Son range in the north-west. Along its western, inland border, Vietnam's neighbours are Lao PDR and Cambodia. To its north is China, to the south and east the South China Sea or Gulf of Tonkin. Mean annual rainfall is about 2,000 mm: higher in some central areas, where it may reach 3,000 mm, and lowest along the south-east coast, 500 mm. -

Greater Mekong Subregion Core Environment Program 10 Years of Cooperation

Greater Mekong Subregion Core Environment Program 10 Years of Cooperation This publication was compiled to celebrate the first 10 years of the Greater Mekong Subregion Core Environment Program (CEP). It provides an overview of the environment issues the program has worked on, as well as its solutions, achievements, and future priorities. The articles and stories featured within aim to highlight the CEP’s work, using the voices and perspectives of its partners and beneficiaries. About the Asian Development Bank ADB is committed to achieving a prosperous, inclusive, resilient, and sustainable Asia and the Pacific, while sustaining its efforts to eradicate extreme poverty. Established in 1966, it is owned by 67 members— 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. About the Core Environment Program The Core Environment Program (CEP) supports the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS) in delivering environmentally friendly economic growth. Anchored on the ADB-supported GMS Economic Cooperation Program, the CEP promotes regional cooperation to improve development planning, safeguards, biodiversity conservation, and resilience to climate change—all of which are underpinned by capacity Greater Mekong Subregion building. The CEP is overseen by the environment ministries of the six GMS countries and implemented by the ADB-administered Environment Operations Center. Cofinancing is provided by ADB, the Global Environment Facility, -

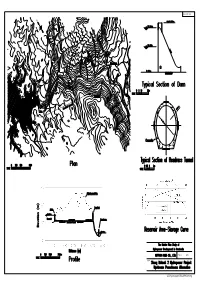

11925773 07.Pdf

Final Report Appendix-B Results of Natural Environment Survey by Subcontractor APPENDIX-B RESULTS OF NATUAL ENVIRONMENT SURVEY BY SUBCONTRACTOR NATURAL ENVIRONMENT The rapid economic growth of Cambodia in recent years drives a huge demand for electricity. A power sector strategy 1999–2016 was formulated by the government in order to promote the development of renewable resources and reduce the dependency on imported fossil fuel. The government requested technical assistance from Japan to formulate a Master Plan Study of Hydropower Development in Cambodia. The objective of this paper is to survey the natural and social environment of 10 potential hydropower projects in Cambodia that can be grouped into six sites as listed below. This survey constitutes part of the Master Plan Study of Hydropower Development in Cambodia. The objective of the survey is to gather baseline information on the current conditions of the sites, which will be used as input for a review and prioritisation of the selected project sites. This report indicate the natural environment of the following projects on 6 basins. Original Site No. Name of Project Provice Protected Area (Abbreviation) 1 No. 12, 13 & 14 Prek Liang I, IA, II Ratanak Kiri Virachey National Park (VNP) 2 No. 7 & 8 Lower Se San II & Lower Stung Treng - Sre PokII 3 No. 29 Bokor Plateau Kampot Bokor National Park (BNP) 4 No. 22 Stung Kep II Koh Kong Southern Cardamom Protected Forest (SCPF) 5 No. 16 & 23 Middle and Upper Stung Koh Kong Central Cardamom Protected Forest Russey Chrum (CCPF) 6 No. 20 & 21 Stung Metoek II, III Pursat & Koh Phnom Samkos Wildlife Sanctuary Kong (PSWS) No.