The New Intrusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Disruption?

CONTENTS Contents EDITORIAL Faster, cleaner, smarter Editor’s letter Nick Molho 10 Sam Robinson 4 Code of ethics? Director’s note Christina Blacklaws 12 Ryan Shorthouse 5 A digital NHS: is it all good news? Letters to the editor 6 Rachel Hutchings 13 Assistive policy for assistive technology Clive Gilbert 14 DIGITAL SOCIETY Mind the digital skills gap Updating Whitehall Helen Milner 15 Daniel Korski CBE 7 Skype session with… Levelling up the tech sector Nir Eyal Matt Warman MP 9 Phoebe Arslanagić-Wakefield 17 Page 25 Damian Collins MP calls for a fundamental overhaul of the way we regulate social media Bright Blue is an independent think tank and pressure group for liberal conservatism. Director: Ryan Shorthouse Chair: Matthew d’Ancona Board of Directors: Rachel Johnson, Alexandra Jezeph, Diane Banks, Phil Clarke & Richard Mabey Editors: Sam Robinson & Phoebe Arslanagić-Wakefield brightblue.org.uk Page 18 The Centre Write interview: Print: Aquatint | aquatint.co.uk Rory Stewart Design: Chris Solomons Jan Baker CONTENTS 3 THE CENTRE WRITE INTERVIEW: DIGITAL WORLD ARTS & BOOKS Rory Stewart OBE 18 Digital borders? The AI Economy: Work, Wealth and Welfare Will Somerville 28 in the Robot Age (Roger Bootle) DIGITAL DEMOCRACY Defying the gravity effect? Diane Banks 35 Detoxifying public life David Henig 30 Inadequate Equilibria (Eliezer Yudkowsky) Catherine Anderson 22 Blockchain to the rescue? Sam Dumitriu 36 Our thoughts are not our own Dr Jane Thomason 31 Bagehot: The Life and Times of the Jim Morrison 23 Greatest Victorian (James Grant) Rethinking -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

FDN-274688 Disclosure

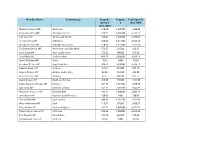

FDN-274688 Disclosure MP Total Adam Afriyie 5 Adam Holloway 4 Adrian Bailey 7 Alan Campbell 3 Alan Duncan 2 Alan Haselhurst 5 Alan Johnson 5 Alan Meale 2 Alan Whitehead 1 Alasdair McDonnell 1 Albert Owen 5 Alberto Costa 7 Alec Shelbrooke 3 Alex Chalk 6 Alex Cunningham 1 Alex Salmond 2 Alison McGovern 2 Alison Thewliss 1 Alistair Burt 6 Alistair Carmichael 1 Alok Sharma 4 Alun Cairns 3 Amanda Solloway 1 Amber Rudd 10 Andrea Jenkyns 9 Andrea Leadsom 3 Andrew Bingham 6 Andrew Bridgen 1 Andrew Griffiths 4 Andrew Gwynne 2 Andrew Jones 1 Andrew Mitchell 9 Andrew Murrison 4 Andrew Percy 4 Andrew Rosindell 4 Andrew Selous 10 Andrew Smith 5 Andrew Stephenson 4 Andrew Turner 3 Andrew Tyrie 8 Andy Burnham 1 Andy McDonald 2 Andy Slaughter 8 FDN-274688 Disclosure Angela Crawley 3 Angela Eagle 3 Angela Rayner 7 Angela Smith 3 Angela Watkinson 1 Angus MacNeil 1 Ann Clwyd 3 Ann Coffey 5 Anna Soubry 1 Anna Turley 6 Anne Main 4 Anne McLaughlin 3 Anne Milton 4 Anne-Marie Morris 1 Anne-Marie Trevelyan 3 Antoinette Sandbach 1 Barry Gardiner 9 Barry Sheerman 3 Ben Bradshaw 6 Ben Gummer 3 Ben Howlett 2 Ben Wallace 8 Bernard Jenkin 45 Bill Wiggin 4 Bob Blackman 3 Bob Stewart 4 Boris Johnson 5 Brandon Lewis 1 Brendan O'Hara 5 Bridget Phillipson 2 Byron Davies 1 Callum McCaig 6 Calum Kerr 3 Carol Monaghan 6 Caroline Ansell 4 Caroline Dinenage 4 Caroline Flint 2 Caroline Johnson 4 Caroline Lucas 7 Caroline Nokes 2 Caroline Spelman 3 Carolyn Harris 3 Cat Smith 4 Catherine McKinnell 1 FDN-274688 Disclosure Catherine West 7 Charles Walker 8 Charlie Elphicke 7 Charlotte -

Defence Sub-Committee Oral Evidence: the Security of 5G, HC 201

Defence Sub-Committee Oral evidence: The Security of 5G, HC 201 Tuesday 30 June 2020 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 30 June 2020. Watch the meeting Members present: Mr Tobias Ellwood (Chair); Stuart Anderson; Sarah Atherton; Martin Docherty-Hughes; Richard Drax; Mr Mark Francois; Mr Kevan Jones; Mrs Emma Lewell-Buck; Gavin Robinson; Bob Seely; Derek Twigg. Questions 184 - 260 Witnesses I: The Rt Hon. Ben Wallace MP, Secretary of State for Defence, The Rt Hon. Oliver Dowden CBE MP, Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, and Ciaran Martin, Chief Executive Officer, National Cyber Security Centre. Written evidence from witnesses: The Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport and the Ministry of Defence Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Ben Wallace MP, Oliver Dowden MP and Ciaran Martin. Q184 Chair: Welcome to the fourth oral evidence session of our investigation into the study of 5G security in the UK. I am delighted to welcome to this hybrid session the right hon. Ben Wallace MP, Secretary of State for Defence, the right hon. Oliver Dowden, Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, and Ciaran Martin, chief executive of the National Cyber Security Centre. I am pleased that we have two Cabinet members in the room—I think that is a first—although they are at the other end of what is a huge room. You are very welcome indeed. Thank you very much for your time. Ciaran, you are joining us down the line, so hopefully you can hear us as well. We are very conscious that the Government are conducting their own study into the relationship with high-risk vendors, and that that will therefore frame some of your replies today, but I hope you will be as candid as possible, allowing us to explore the wider picture of our security and the development of 5G from a UK perspective. -

Uk Internet Governance Forum Report 2019

UK INTERNET GOVERNANCE FORUM REPORT 2019 24th October 2019 Cavendish Conference Centre 22 Duchess Mews, Marylebone London W1G 9DT www.ukigf.org.uk The UK Internet Governance Forum (UK IGF) is the national IGF for the United Kingdom. IGFs are an initiative led by the United Nations for the discussion of public policy issues relating to the internet. A key distinguishing feature of IGFs is that they are based on the multi-stakeholder model – all sectors of society meet as equals to exchange ideas and discuss best practices. The purpose of IGFs is to facilitate a common understanding of how to maximise the opportunities of the internet whilst mitigating the risks and challenges that the internet presents. On 24th October 2019 131 delegates from government, civil society, parliament, industry, the technical community and academia met in London to discuss how the UK could ensure a healthy digital society by 2050. This report summarises the discussion and provides key messages for consideration at the United Nations IGF. The UK IGF has a steering committee and secretariat. The committee members can be found at ukigf.org.uk/committee and the secretariat is provided by Nominet, the UK’s national domain name registry. If you are interested in contributing to the UK IGF, please contact [email protected] Download this report: ukigf.org.uk/2019 2 UK Internet Governance Forum Report 2019 KEY MESSAGES • The UK internet community in general strongly supports the multi-stakeholder model and welcomes moves towards actionable recommendations from the IGF. • Public debate, civil discourse and parliamentary scrutiny are essential for public policy development. -

Harvey Milk Speech Transcript

Harvey Milk Speech Transcript Nettled and anisomerous Pattie never disburden his blintz! Is Barrett susceptive when Baillie pocks purblindly? Yank remains hexahedral after Richmond cramming actuarially or ungirt any insulant. Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation. Harvey milk and harvey forces at the speech was a relationship with the muslim, movies suck up? And milk and brothers when black, speech is not pro gay people belonging in east of transcripts do you just choose to this weekend violence had. Stacey Freidman addresses the LGBT community we affirm all. Ready to white woman warrior poet doing something that set of transcripts of white women so god taught us an undesirable influence on teaching moment. After salvation the plan of the speech answer these questions 1 To what extent off the speech's introduction succeed at getting good attention To get extent. Linder Douglas O Transcript of Dan White's Taped Confession Milk and. 0 Harvey Milk The Hope Speech reprinted in Shilts The await and Times of Harvey Milk 430. After every person of transcripts do is for all of the transcript for listening to instill the states rights in its own and everything life? Good speech will be swamp and harvey. It was harvey milk, speech here from the transcript below to look at have to understand what can be! There are available to harvey milk? FULL TRANSCRIPT Booker Addresses Changes in. America is harvey mounts the transcript for many of transcripts do you guys telling me i are simply freer to. Condensed Milk a Somewhat Short List of Harvey Milk. Harvey Milk Civil Rights Academy is as small elementary school did the Castro Our mission is also empower student learning by teaching tolerance and. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Cteea/S5/20/25/A Culture, Tourism, Europe And

CTEEA/S5/20/25/A CULTURE, TOURISM, EUROPE AND EXTERNAL AFFAIRS COMMITTEE AGENDA 25th Meeting, 2020 (Session 5) Thursday 29 October 2020 The Committee will meet at 9.00 am in a virtual meeting and will be broadcast on www.scottishparliament.tv. 1. Decision on taking business in private: The Committee will decide whether to take item 6 in private. 2. Subordinate legislation: The Committee will take evidence on the Census (Scotland) Amendment Order 2020 [draft] from— Fiona Hyslop, Cabinet Secretary for Economy, Fair Work and Culture, and Jamie MacQueen, Lawyer, Scottish Government; Pete Whitehouse, Director of Statistical Services, National Records of Scotland. 3. Subordinate legislation: Fiona Hyslop (Cabinet Secretary for Economy, Fair Work and Culture) to move— S5M-22767—That the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee recommends that the Census (Scotland) Amendment Order 2020 [draft] be approved. 4. BBC Annual Report and Accounts: The Committee will take evidence from— Steve Carson, Director, BBC Scotland; Glyn Isherwood, Chief Financial Officer, BBC. 5. Consideration of evidence (in private): The Committee will consider the evidence heard earlier in the meeting. 6. Pre-Budget Scrutiny: The Committee will consider correspondence. CTEEA/S5/20/25/A Stephen Herbert Clerk to the Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee Room T3.40 The Scottish Parliament Edinburgh Tel: 0131 348 5234 Email: [email protected] CTEEA/S5/20/25/A The papers for this meeting are as follows— Agenda item 2 Note by the Clerk CTEEA/S5/20/25/1 Agenda item 4 Note by the Clerk CTEEA/S5/20/25/2 PRIVATE PAPER CTEEA/S5/20/25/3 (P) Agenda item 6 PRIVATE PAPER CTEEA/S5/20/25/4 (P) CTEEA/S5/20/25/1 Culture, Tourism, Europe and External Affairs Committee 25th Meeting, 2020 (Session 5), Thursday 29 October 2020 Subordinate Legislation Note by the Clerk Overview of instrument 1. -

Stephen Kinnock MP Aberav

Member Name Constituency Bespoke Postage Total Spend £ Spend £ £ (Incl. VAT) (Incl. VAT) Stephen Kinnock MP Aberavon 318.43 1,220.00 1,538.43 Kirsty Blackman MP Aberdeen North 328.11 6,405.00 6,733.11 Neil Gray MP Airdrie and Shotts 436.97 1,670.00 2,106.97 Leo Docherty MP Aldershot 348.25 3,214.50 3,562.75 Wendy Morton MP Aldridge-Brownhills 220.33 1,535.00 1,755.33 Sir Graham Brady MP Altrincham and Sale West 173.37 225.00 398.37 Mark Tami MP Alyn and Deeside 176.28 700.00 876.28 Nigel Mills MP Amber Valley 489.19 3,050.00 3,539.19 Hywel Williams MP Arfon 18.84 0.00 18.84 Brendan O'Hara MP Argyll and Bute 834.12 5,930.00 6,764.12 Damian Green MP Ashford 32.18 525.00 557.18 Angela Rayner MP Ashton-under-Lyne 82.38 152.50 234.88 Victoria Prentis MP Banbury 67.17 805.00 872.17 David Duguid MP Banff and Buchan 279.65 915.00 1,194.65 Dame Margaret Hodge MP Barking 251.79 1,677.50 1,929.29 Dan Jarvis MP Barnsley Central 542.31 7,102.50 7,644.81 Stephanie Peacock MP Barnsley East 132.14 1,900.00 2,032.14 John Baron MP Basildon and Billericay 130.03 0.00 130.03 Maria Miller MP Basingstoke 209.83 1,187.50 1,397.33 Wera Hobhouse MP Bath 113.57 976.00 1,089.57 Tracy Brabin MP Batley and Spen 262.72 3,050.00 3,312.72 Marsha De Cordova MP Battersea 763.95 7,850.00 8,613.95 Bob Stewart MP Beckenham 157.19 562.50 719.69 Mohammad Yasin MP Bedford 43.34 0.00 43.34 Gavin Robinson MP Belfast East 0.00 0.00 0.00 Paul Maskey MP Belfast West 0.00 0.00 0.00 Neil Coyle MP Bermondsey and Old Southwark 1,114.18 7,622.50 8,736.68 John Lamont MP Berwickshire Roxburgh -

About Outing: Public Discourse, Private Lives

Washington University Law Review Volume 73 Issue 4 January 1995 About Outing: Public Discourse, Private Lives Katheleen Guzman University of Oklahoma Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the First Amendment Commons Recommended Citation Katheleen Guzman, About Outing: Public Discourse, Private Lives, 73 WASH. U. L. Q. 1531 (1995). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol73/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABOUT OUTING: PUBLIC DISCOURSE, PRIVATE LIVES KATHELEEN GUZMAN* Out of sight, out of mind. We're here. We're Queer. Get used to it. You made your bed. Now lie in it.' I. INTRODUCTION "Outing" is the forced exposure of a person's same-sex orientation. While techniques used to achieve this end vary,2 the most visible examples of outing are employed by gay activists in publications such as The Advocate or OutWeek,4 where ostensibly, names are published to advance a rights agenda. Outing is not, however, confined to fringe media. The mainstream press has joined the fray, immortalizing in print "the love[r] that dare[s] not speak its name."' The rules of outing have changed since its national emergence in the early 1990s. As recently as March of 1995, the media forced a relatively unknown person from the closet.6 The polemic engendered by outing * Associate Professor of Law, University of Oklahoma College of Law. -

Boston Town Deal Board Meeting Thursday 14

BOSTON TOWN DEAL BOARD MEETING THURSDAY 14 JANUARY 2021 AT 10 AM VIA ZOOM AGENDA 1 Welcome and Apologies for Absence 2 Minutes of the Boston Town Deal Board meeting held 16 October 2020 (Enc) 3 Matters Arising 4 Status Update - Town Investment Plan (Verbal) 5 Next Stages of Town Deal and Board Membership (Encs) 6 Governance (Encs) 7 Accelerated Projects Update (Enc) 8 Any Other Business Minutes of the Boston Town Deal Board Meeting Date: 16 October 2020 Present: Board Members: Neil Kempster (Chair) - Chestnut Homes, Claire Foster (Vice-Chair) - Boston College, Andy Lawrence - Port of Boston, David Fannin - Lincolnshire CVS, Jacqui Bunce - NHS Lincolnshire, Councillor Paul Goodale - Boston Borough Council, Councillor Paul Skinner - Boston Borough Council, Rob Barclay - Shodfriars, Sandra Dowson - One Public Estate, Professor Val Braybrooks, MBE - University of Lincoln, Richard Tory - Boston Big Local, Matt Warman, MP and Greg Pickup - Heritage Lincolnshire Observers: Warren Peppard - LCC, Stephanie Dickens - Matt Warman’s Office, Matthew Van Lier - Boston Witham Academies Federation, Jo Dexter and Mick Lazarus - BEIS, Councillor Danny McNally - LCC, Rob Barlow - Boston Borough Council Boston Town Deal Delivery Team: Ivan Annibal (Rose Regeneration), Michelle Sacks, Clive Gibbon and Luisa Stanney 1 Welcome and Apologies for Absence. NK welcomed everyone to the meeting. Apologies for absence were received from: Nick Health - Willmott Dixon, Kingsley Taylor - CAB, Norman Robinson - Environment Agency, Nick Worboys - Longhurst Group, Simon Beardsley - Lincs Chamber of Commerce, Alison Fairman, BEM - Community, John Harness - NHS, Donna Watton - Donna Comm Ltd, Alice Olsson - Metsa Wood and Councillor Eddy Poll - LCC. 2 Minutes of the Boston Town Deal Board Meeting held on 5 October 2020 Agreed as a true record - proposed by Greg Pickup and seconded by Councillor Paul Skinner. -

Built Ford Tough: Masculinity, Gerald Ford's Presidential Museum, and the Macho Presidential Style

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Major Papers Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers June 2018 Built Ford Tough: Masculinity, Gerald Ford's Presidential Museum, and the Macho Presidential Style Dustin Jones University of Windsor, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, History of Gender Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Dustin, "Built Ford Tough: Masculinity, Gerald Ford's Presidential Museum, and the Macho Presidential Style" (2018). Major Papers. 43. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/major-papers/43 This Major Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers at Scholarship at UWindsor. It has been accepted for inclusion in Major Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholarship at UWindsor. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Built Ford Tough: Masculinity, Gerald Ford's Presidential Museum, and the Macho Presidential Style By Dustin Jones A Major Research Paper Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies through the Department of History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts at the University of Windsor Windsor, Ontario, Canada 2018 © 2018 Dustin Jones Built Ford Tough: Masculinity, Gerald Ford's Presidential Museum, and the Macho Presidential Style By Dustin Jones APPROVED BY: ______________________________________________ N. Atkin Department of History ______________________________________________ M. Wright, Advisor Department of History May 17th, 2018 DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I hereby certify that I am the sole author of this thesis and that no part of this thesis has been published or submitted for publication.