Bhutan SLM TE Report.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engthen the Financial Management System the General Auditing Rules and Regulations (GARR) Was Issued in 1989

Annual Audit Report 2004 Part I Background By virtue of the Kashos and the provisions contained in the General Auditing Rules and Regulations of Bhutan (GARR), the Royal Audit Authority (RAA), the Supreme Audit Institution (SAI) of Bhutan is responsible for audit of public sector agencies and reporting its findings. In 1961, the 16th Session of the National Assembly of Bhutan formed a committee of Accounts and Audit in response to the need for establishing accountability. The Committee would comprise of one representative of the King and one representative each from the Cabinet, People and the Monk Body all nominated by the King. The Royal Government issued the first edition of the Financial Manual in 1963. The manual provided for the organization of the Development Wing of the government and the Accounts and Audit for the Development Wing. The Accounts and Audit Wing maintained the books of accounts, conducted budgetary controls of revenues and expenditures, and undertook periodic audit and inspection of accounts and records. In October 1969 the 31st Session of the National Assembly based on a motion proposed by the King to delegate the auditing authority voted for the appointment of Royal Auditors to conduct the audit of accounts and records of the Royal Government. Consequently, the four Royal Auditors were appointed on 16th April 1970 under a Royal Kasho. The Kasho defined and authorized the jurisdiction of the then Royal Audit Department as primarily responsible for the audit of accounts of the Ministry of Finance, Ministries, the Royal Bhutan Army, the Royal Bhutan Police and His Majesty’s Secretariat. -

Third Parliament of Bhutan First Session

THIRD PARLIAMENT OF BHUTAN FIRST SESSION Resolution No. 01 PROCEEDINGS AND RESOLUTION OF THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY OF BHUTAN (January 2 - 24, 2019) Speaker: Wangchuk Namgyel Table of Content 1. Opening Ceremony..............................................................................1 2. Question Hour: Group A- Questions to the Prime Minister, Ministry of Home and Cultural Affairs, and Ministry of Information and Communication..............................3 3. Endorsement of Committees and appointment of Committee Members......................................................................5 4. Report on the National Budget for the FY 2018-19...........................5 5. Report on the 12th Five Year Plan......................................................14 6. Question Hour: Group B- Questions to the Ministry of Works and Human Settlement, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Agriculture and Forests................................21 7. Resolutions of the Deliberation on 12th Plan Report.........................21 8. Resolutions of the Local Government Petitions.................................28 9. Question Hour: Group C: Questions to the Ministry of Economic Affairs, Ministry of Finance, and Ministry of Labour and Human Resources....................................................33 10. Resolutions on the Review Report by Economic and Finance Committee on the Budget of Financial Year 2018-2019........................................................................................36 11. Question Hour: Group D: Questions to the -

Government of Sikkim Office of the District Collector South District Namchi

GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM OFFICE OF THE DISTRICT COLLECTOR SOUTH DISTRICT NAMCHI COI APPLICATION STATUS AS ON 26-July-2018 ApplicationDate : 28/12/2017 00:00AM COIFormNo Applicant Name Father/Husband Name Block Status Status Date 25969 PRATAP SINGH TAMANG KARNA BAHADUR DOROP Application Received 28/12/2017 TAMANG 25971 PHURBA TAMANG KARNA BAHADUR DOROP Application Received 28/12/2017 TAMANG 25968 SARDA KHANAL RAM PRASAD BRAHMAN NAGI Application Received 28/12/2017 25972 SABNAM SHERPA PREM TSHERING PERBING Application Received 28/12/2017 SHERPA ApplicationDate : 27/12/2017 00:00AM COIFormNo Applicant Name Father/Husband Name Block Status Status Date 25956 REJITA RAI (RAJALIM) KISHOR RAI SALGHARI Application Received 27/12/2017 25955 BISHNU DOLMA TAMANG BUDHA DORJEE DHARGOAN Application Received 27/12/2017 TAMANG 25950 KARMA ONGYAL BHUTIA NORBU TSHERING THANGSING Application Received 27/12/2017 BHUTIA 25959 JIT BAHADUR TAMANG RAN BAHADUR TAMANG DOROP Application Received 27/12/2017 25958 MICKLE TAMANG RAM KUMAR TAMANG DOROP Application Received 27/12/2017 25949 DIVEYA RAI AMBER BAHADUR RAI KAMAREY Application Received 27/12/2017 25961 BIJAY MANGER KAMAL DAS MANGER DHARGOAN Application Received 27/12/2017 25960 NIRMAL TAMANG AMBER BAHADUR DOROP Application Received 27/12/2017 TAMANG 25957 PRALAD TAMANG RAM KUMAR TAMANG DOROP Application Received 27/12/2017 25966 WANGDUP DORJEE RAJEN TAMANG BOOMTAR Application Received 27/12/2017 TAMANG 25948 DAL BAHADUR LIMBOO KHARKA BAHADUR TINGMO Certificate Printed 12/01/2018 LIMBOO COI APPLICATION STATUS -

Shechangthang (Ranibagan) Local Area Plan Volume 01

01 Shechangthang 2010-2035 Shechangthang Local Area Plan Final Report – Volume 01 Department of Human Settlement, MoWHS, Thimphu Shechangthang (Ranibagan) Local Area Plan Volume 01 Department of Human Settlement, Ministry of Works & Human Settlement (MoWHS), Thimphu _____________________________________________________________________________ Shechangthang (Ranibagan) Local Area Plan Table of Contents Table of Contents 1.0 INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 6 1.1 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES ....................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 VISION AND APPROACH ...................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 PEOPLE’S PARTICIPATION IN THE PLAN FORMULATION: ............................................................................ 9 1.3.1 What is a Local Area Plan? ................................................................................................... 9 1.3.2 Land Pooling ......................................................................................................................... 9 1.3.3 The Planning Process .......................................................................................................... 10 1.3.4 Participation ....................................................................................................................... 10 1.3.5 Integration of the Local Area -

International Journal Bhutan & Himalayan Research

Inaugural Issue 2020 DRUK & HIMALAYA IJBHR | Inaugural Issue | Autumn 2020 འབག་དང་ཧི་མ་ལ་ཡ། ARTICLES PERSPECTIVES Sonam Kinga Chador Wangmo, Rinzin Rinzin and One Journey, Three Poems; One Serf, Namgyal Tshering Three Lords: Literary compositions about Perspectives on Contemporary Bhutanese International Journal Ugyen Wangchuck’s Peace Mission to Literature Internationalfor Journal Lhasa, 1904 Ugyen Tshomo, Pema Wangdi Sonam Nyenda Contemporary Children’s Literature in Challenges to the Development of Bhutan Dzongkha Literature: A comparision of Rnam thar and Srung CONFERENCE REPORT for Tshering Om Tamang Anden Drolet Exploring National Identity through The Inaugural Conference of the Literature in Bhutanese National English International Society for Bhutan Studies Bhutan & Himalayan Curriculum BOOK REVIEW Holly Gayley Karma and Female Agency in Novels Eben Yonnetti Research by Bhutanese Women Writers Old Demons, New Deities: Twenty-One Short Stories from Tibet. Bhutan & Himalaya Research Centre College of Language and Culture Studies Royal University of Bhutan ISSN: 2709-3352(print) Bhutan & Himalaya Research Centre ISSN: 2709-3360(online) འབག་དང་ཧི་མ་ལ་ཡ། InternationalInternational Journal Journal for Bhutan & Himalayan Research About the Journal for IJBHR is an annual, peer reviewed, open access journal published by the Bhutan and Himalaya Research Centre (BHRC), at the College of Language and Culture Studies, Royal University of Bhutan. IJBHR aims to advance research and scholarship in all felds pertaining to social and cultural issues, religion and humanities relevant to Bhutan and Himalaya. It will publish a wide range of papers in English and Dzongkha including theoretical or empirical research, perspectives, conference reports and book reviews which can contribute to the scholarship on Bhutan and Himalayan Studies. -

Annexure 2.Xlsx

Annexure 2 Total Registered Voter Results Sl. No PARTY CANDIDATE Remarks Male Female Total EVM Votes Postal Votes Total Votes Bumthang Dzongkhag Chhoekhor_Tang Demkhong 1 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Dawa 1126 410 1536 2842 3209 6051 2 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Pema Gyamtsho 2178 1073 3251 TOTAL 3304 1483 4787 Chhumig_Ura Demkhong 1 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Karma Wangchuk 863 570 1433 1762 2023 3785 2 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Phuntsho Namgey 1010 405 1415 TOTAL 1873 975 2848 Chhukha Dzongkhag Bongo_Chapchha Demkhong 1 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Pempa 2501 978 3479 7036 7284 14320 2 DRUK NYAMRUPTSHOGPA Tshewang Lhamo 4493 2139 6632 TOTAL 6994 3117 10111 Phuentshogling Demkhong 1 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Jai Bir Rai 4611 975 5586 5401 5336 10737 2 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Tashi 2065 315 2380 TOTAL 6676 1290 7966 Dagana Dzongkhag Drukjeygang_Tseza Demkhong 1 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Jurmi Wangchuk 3978 2109 6087 6146 6359 12505 2 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Migma Dorji 1977 962 2939 TOTAL 5955 3071 9026 Lhamoi Dzingkha_Tashiding Demkhong 1 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Hemant Gurung 4333 1924 6257 6143 5922 12065 2 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Prem Kumar Khatiwara 1780 808 2588 TOTAL 6113 2732 8845 Gasa Dzongkhag Khamaed_Lunana Demkhong 1 DRUK PHUENSUMTSHOGPA Dhendup 313 48 361 471 570 1041 2 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Yeashey Dem 330 89 419 TOTAL 643 137 780 Khatoed_Laya Demkhong 1 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Changa Dawa 245 23 268 982 1082 2064 2 DRUK NYAMRUP TSHOGPA Tenzin 499 89 588 TOTAL 744 112 856 Haa Dzongkhag Bji_Kar-tshog_Uesu Demkong 1 DRUK PHUENSUM TSHOGPA Sonam Tobgay 669 219 888 1963 2210 4173 -

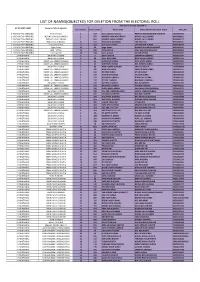

List of Names(Objected) for Deletion from the Electoral Roll

LIST OF NAMES(OBJECTED) FOR DELETION FROM THE ELECTORAL ROLL Particulars of name objected at AC NO AND NAME Name (in full) of objector Part number Serial number Name in full Father/Mother/Husband Name EPIC_NO 1 -YUKSOM TASHIDING(BL) Prem Sharma 1 313 Gauri Shanker Sharma PEM DECHEN DENZONGPA BHUTIA FKD0059956 1 -YUKSOM TASHIDING(BL) MERING HANGMA LIMBOO 1 974 MERING HANGMA LIMBOO NANDA LALL LIMBOO RBS0098202 1 -YUKSOM TASHIDING(BL) PUNNEP HANG LIMBOO 1 981 PUNNEP HANG LIMBOO NANDA LALL LIMBOO RBS0098277 1 -YUKSOM TASHIDING(BL) HARGOVIN AGRAWAL 8 221 HARGOVIN AGRAWAL TEK MAN RAI RBS0068395 1 -YUKSOM TASHIDING(BL) mahaveer meena 9 219 fool chand meena CHATRA BDR. SUBBA FKD0098574 1 -YUKSOM TASHIDING(BL) Sagar Subba 10 82 Sagar Subba DAMBER BAHADUR MANGER RBS0080648 1 -YUKSOM TASHIDING(BL) ANIL LEPCHA 10 303 ANIL LEPCHA MAN BAHADUR GURUNG RBS0059683 1 -YUKSOM TASHIDING(BL) suren prasad 16 746 suren prasad SUNAR LEPCHA GZS0075457 2-YANGTHANG BALA RAM LIMBOO 2 6 NEPTI LEPCHA SONAM TSH LEPCHA FKD0073247 2-YANGTHANG BALA RAM LIMBOO 2 50 PHUL BIR SUBBA RASEN DHOJ LIMBOO FKD0092114 2-YANGTHANG BUDHI LALL LIMBOO (SUBBA) 2 61 BUDHA BIR SUBBA PHUL MAYA SUBBA FKD0092940 2-YANGTHANG BUDHI LALL LIMBOO (SUBBA) 2 66 SEM MAYA SUBBA BOL KANCHA SUBBA FKD0092536 2-YANGTHANG BALA RAM LIMBOO 2 93 RAM KUMAR GURUNG SAPTEN BHUTIA YCN0043869 2-YANGTHANG BUDHI LALL LIMBOO (SUBBA) 2 106 MAN BIR SUBBA SANCHA MAN SUBBA FKD0093575 2-YANGTHANG BUDHI LALL LIMBOO (SUBBA) 2 133 JIT MAN SUBBA JIT BIR SUBBA FKD0092643 2-YANGTHANG BUDHI LALL LIMBOO (SUBBA) 2 134 AITA MAYA SUBBA JIT MAN SUBBA FKD0092650 2-YANGTHANG BUDHI LALL LIMBOO (SUBBA) 2 152 NAR MOTI LIMBOO BUDHI LALL SUBBA FKD0092106 2-YANGTHANG BUDHI LALL LIMBOO (SUBBA) 2 174 JIT BDR. -

Dismissal of Fiscal Incentives Accusations

SATURDAY KUENSELTHAT THE PEOPLE SHALL BE INFORMED JULY 1" ( & ' - D k ' + Briefly Dismissal of fiscal incentives SAARC experts meeting accusations draws criticism begin >> Experts from SAARC countries will NC says the government must establish the legality of the tax incentives given attend a three-day consultation meeting until May 8, 2017 on Water-energy-food nexus in Thimphu from July 3. Researchers will present papers on water security, renewal energy, and sustainable agriculture development. Inside Pg.3: India expresses concern over road construction in Doklam Pg.5: Mental health cases still underreported Pg.9: Choeten and the man Pg.10: PERSPECTIVE: Constitutional framing or a usual bickering? Pg.17: BFF suspends Drukpol FC for two years A step towards MB Subba in a live interview on BBS on June 27, Panbang MP Dorji Wangdi said and at the Meet the Press on June 23, the Prime Minister’s statement 2 preventing corruption rather than fighting he government’s out- dismissed the accusations as unsub- against the Opposition was uncalled K right rejection of the stantiated. The Prime Minister said for. “The PM’s singling out of some against it allegations against it that the accusations of the Opposition business entities is highly mislead- violating the Constitu- and DNT were politically motivated. ing and baffling,” he said. tion by granting the The National Council, the Op- Questioning the timing of the Focus Point TFiscal Incentives 2016 without the position and DNT have hit back at declaration of the Fiscal Incentives parliament’s approval has irked the the Prime Minister over his state- 2013, the Prime Minister said the Opposition, the National Council ment saying that the Prime Min- previous government dissolved just and Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT). -

Contemporary Bhutanse Literature

འབྲུག་དང་ཧི་捱་ལ་ཡ། InternationalInternational Journal for Journal Bhutan & Himalayan for Research Bhutan & Himalayan Research Bhutan & Himalaya Research Center College of Language and Culture Studies Royal University of Bhutan P.O.Box 554, Taktse, Trongsa, Bhutan Email: [email protected] Bhutan & Himalaya Research Centre College of Language and Culture Studies Royal University of Bhutan P.O.Box 554, Taktse, Trongsa, Bhutan Email: [email protected] Copyright©2020 Bhutan and Himalaya Research Centre, College of Language and Culture Studies, Royal University of Bhutan. All rights reserved. The views expressed in this publication are those of the contributors and not necessarily of IJBHR. No parts of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording, or otherwise, without permission from the publisher. Printed at Kuensel Corporation Ltd., Thimphu, Bhutan Articles In celebration of His Majesty the King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck’s 40th birth anniversary and His Majesty the Fourth Druk Gyalpo Jigme Singye Wangchuk’s 65th birth anniversary. IJBHR Inaugural Issue 2020 i འབྲུག་དང་ཧི་捱་ལ་ཡ། International InternationalJournal for Journal for Bhutan & Himalayan Research BhutanGUEST EDITOR & Himalayan Holly Gayley UniversityResearch of Colorado Boulder, USA EDITORS Sonam Nyenda and Tshering Om Tamang BHRC, CLCS MANAGING EDITOR Ngawang Jamtsho Dean of Research and Industrial Linkages, CLCS EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bhutan & Himalaya -

Package of Practices for Organic Rnr Commodities

PACKAGE OF PRACTICES FOR ORGANIC RNR COMMODITIES National Centre for Organic Agriculture National Organic Flagship Programme Department of Agriculture Ministry of Agriculture and Forests May 2020 i EDITOR 1. Dr. Tayan Raj Gurung, Advisor, DoA 2. Dr. Sonam Tashi, Lecturer, CNR 3. Mr. Mahesh Ghimeray, Rice Specialist, ARDC-Bajo 4. Mr. Lakey, Principal Agriculture Officer, ARED, DoA 5. Mr. Tshetrim La, AO, NOFP-CU, DoA TECHNICAL CONTRIBUTORS: 1. Mr. Tirtha Bdr. Katwal, PD, NCOA-Yusipang 2. Ms. Kesang Tshomo, PM, NOFP-CU, DoA 3. Mr. Passang Tshering, AO, ARDC-Bajo 4. Mr. Ganga Ram Ghalley, AO, ARDC-Samtenling 5. Mr. Tshering Tobgay, AO, ARDC-Samtenling 6. Ms. Tashi Gyelmo,Sr. HO, NCOA-Yusipang 7. Ms. Tshering Zam, Sr. AO, NCOA-Yusipang 8. Ms. Dawa Dem, HO, NCOA-Yusipang 9. Mr. Norbu, AO, NMC, Wangchutaba 10. Ms. Ganga Maya Rizal, Dy. Chief Feed and Fodder Officer, DoL 11. Mr. Jambay Gyeltshen, PD, NRDCAN, DoL, Bhumthang 12. Mr. Jambay Tshewang, LPS, Haa 13. Mr. Sona Darjay, FO, Mongar 14. Mr. Deepak Rai, Specialist, NSC 15. Mr. Tshetrim La, AO, NOFP-CU, DoA 16. Ms. Nima Dolma Tamang, NCOA-Yusipang ILLUSTRATIONS, LAYOUT AND DESIGN BY: 1. Mr. Tshetrim La, AO, NOFP-CU,DoA @ NCOA 2020, Department of Agriculture, MoAF Published By: National Organic Flagship Programme Department of Agriculture Ministry of Agriculture and Forests Tel# 02-322228/331316/336462/336186(F) ISBN 978-99980-919-2-4 i FOREWARN The Department of Agriculture is delighted to publish the first edition of package of practices (PoP) for organic RNR Commodities. Organic Agriculture is a sustainable approach to food production with several positive ecological impacts. -

འབྲུག་གི་བཙག་འཐུ་ལྷན་ཚོགས། Election Commission of Bhutan

འབྲུག་གི་བཙག་འཐུ་ལྷན་ཚོགས། ELECTION COMMISSION OF BHUTAN (Ensuring Free, Fair & Democratic Elections & Referendums) ECB/NOTIF-01/2018/990 Dated: 19th October 2018 NOTIFICATION Subject: Declaration of the Results of the Third Parliamentary Elections 2018: General Election to the National Assembly The Election Commission of Bhutan under Section 443 of the Election Act of the Kingdom of Bhutan 2008 has the honour to hereby notify the names of the Candidates elected from the 47 National Assembly Demkhongs in the Third Parliamentary Election 2018: General Election to National Assembly 2018 with the Poll Day on 18th October 2018 as follows: Name of Party of Sl. Name of Elected Demkhong the Elected No. Candidates Candidates 1 Chhoekhor_ Tang Pema Gyamtsho DPT 2 Chhumig_ Ura Karma Wangchuk DPT 3 Bongo_ Chapchha Tshewang Lhamo DNT 4 Phuentshogling Jai Bir Rai DNT 5 Drukjeygang_ Tseza Jurmi Wangchuk DNT 6 Lhamoi Dzingkha_ Tashiding Hemant Gurung DNT 7 Khamaed_ Lunana Yeashey Dem DNT 8 Khatoed_Laya Tenzin DNT 9 Bji_Kar-Tshog_Uesu Ugen Tenzin DNT Sangbaykha 10 Dorjee Wangmo DNT 11 Gangzur_ Minjey Kinga Penjor DNT Post Box No.: 2008, Democracy House, Kawajangsa, Thimphu: Bhutan 334851, 334852 (PABX),334762 (EA to CEC), Fax: 334763 Website: www.ecb.bt E-mail: [email protected] 12 Maenbi_ Tsaenkhar Choki Gyeltshen DPT 13 Dramedtse_ Ngatshang Ugyen Wangdi DPT 14 Kengkhar_ Weringla Rinzin Jamtsho DPT 15 Monggar Sherub Gyeltshen DNT 16 Dokar_Sharpa Namgay Tshering DNT 17 Lamgong_ Wangchang Ugyen Tshering DNT 18 Khar_Yurung Tshering Chhoden DPT 19 Nanong_ Shumar -

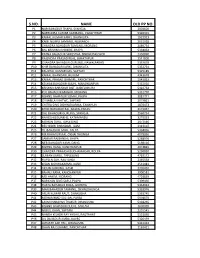

S.No. Name Old Pp No

S.NO. NAME OLD PP NO. P1 NAR BAHADUR THAPA, SYANGJA 2003600 P2 NARENDRA KUMAR KAMBANG, PANCHTHAR 5326301 P3 KAMAL KUMAR KARKI, DHANKUTA 1922923 P4 KAMI NURPU TAMANG, NUWAKOT 2031928 P5 CHANDRA BAHADUR TAMANG, MORANG 2089734 P6 BAL KRISHNA GHIMIRE, JHAPA 5334032 P7 RATNA BAHADUR SHRESTHA, SINDHUPALCHOK 2350890 P8 RAJENDRA PRASAD RIJAL, BHAKTAPUR 2511800 P9 CHANDRA BAHADUR GURUNG, NAWALPARASI 5333678 P10 KHIR BAHADUR KARKI, DHANKUTA 5333734 P11 KAUSHAL KUMAR DAS, SAPTARI 5325189 P12 KAMAL BHANDARI, RUKUM 4343678 P13 KAMAL PRASAD GHIMIRE, PANCHTHAR 1943823 P14 KESHAB BAHADUR MAJHI, MAKAWANPUR 5332010 P15 KRISHNA BAHADUR BIST, DADELDHURA 5322764 P16 KUL BAHADUR MAGAR, MORANG 5331770 P17 BISHNU BAHADUR SOMAI, PALPA 3081721 P18 CHHABILA KHATWE, SAPTARI 2073821 P19 CHITRA SING BISHWOKARMA, TANAHUN 1870473 P20 BHIM BAHADUR RAI, NAWALPARASI 2172957 P21 DAL BAHADUR GURUNG, SYANGJA 2560734 P22 RAMESH BISUNKHE, KATHMANDU 3279933 P23 MOHAN OJHA, TAPLEJUNG 2473546 P24 BED NIDHI BHANDARI, ILAM 3313107 P25 TIL BAHADUR SARU, PALPA 5334026 P26 BIR BAHADUR RAI, OKHALDHUNGA 4078036 P27 SANKAR RAJBANSHI, JHAPA 5268976 P28 NEB BAHADUR KAMI, DANG 5198116 P29 BISHNU RANA, KANCHANPUR 4074891 P30 CHANDRA PRAKASH BUDHAMAGAR, ROLPA 5290850 P31 SUMAN LIMBU, TAPLEJUNG 4719172 P32 RUPSEN SAH, RAUTAHAT 2365558 P33 KISAN BISHWAKARMA, KASKI 2531481 P34 ARJUN GURUNG, KASKI 2709420 P35 BAHALI RANA, KANCHANPUR 3900581 P36 MO HAKIM, MORANG 4729639 P37 NARAYAN SING SARU, PALPA 5309460 P38 HASTA BAHADUR ROKA, GORKHA 5334044 P39 MAN BAHADUR TAMANG, OKHALDHUNGA 5333976 P40 ARUN