Towards a Corpus of Kanien'kéha (Mohawk)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Become a Human Being the Message of Tadodaho Chief Leon Shenandoah 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TO BECOME A HUMAN BEING THE MESSAGE OF TADODAHO CHIEF LEON SHENANDOAH 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Leon Shenandoah | 9781571743411 | | | | | To Become a Human Being The Message of Tadodaho Chief Leon Shenandoah 1st edition PDF Book Hidden categories: All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from May Perhaps one of the most profound books I have ever read. The memory of our circles in the early mornings as we gathered to give Thanksgiving to brother Sun is a sacred seed that sits in our minds, with the sacred fire in our hearts. He gave us a good mind to think clearly. Search Search for:. Then our Hopi brothers from the south would give their thanks to brother sun. With the Good Mind, our circles, councils, and ceremonies create healing through disciplining our minds for life around us. Every year, we gathered in a place where there was a need to strengthen traditional Native culture and restore balance on respected Native territory. The Native American way of life has kept its people close to their living roots. Our elders taught us all natural life is a part of the Native way of life, and this is how our children learn from the old ones how to keep happy, healthy, and feeling strong with the life around them in harmony. Sort order. Nobody else does either. Leon was also a leader of the Onondaga Nation. We are all the Creator's people. Download as PDF Printable version. Friend Reviews. Read more More Details Sam rated it it was amazing Jan 04, I say they can find their ceremony if they use the good mind. -

Press Release for Spoken Here Published by Houghton Mifflin

Press Release Spoken Here by Mark Abley • Introduction • A Conversation with Mark Abley • Glossary of Threatened Languages • Praise for Spoken Here Introduction Languages are beautiful, astoundingly complex, living things. And like the many animals in danger of extinction, languages can be threatened when they lack the room to stretch and grow. In fact, of the six thousand languages in the world today, only six hundred may survive the next century. In Spoken Here, journalist Mark Abley takes us on a world tour — from the Arctic Circle to the outback of Australia — to track obscure languages and reveal their beauty and the devotion of those who work to save them. Abley is passionate about two things: traveling to remote places and seeking out rarities in danger of being lost. He combines his two passions in Spoken Here. At the age of forty-five, he left the security of home and job to embark on a quixotic quest to track language gems before they disappear completely. On his travels, Abley gives us glimpses of fascinating people and their languages: • one of the last two speakers of an Australian language, whose tribal taboos forbid him to talk to the other • people who believe that violence is the only way to save a tongue • a Yiddish novelist who writes for an audience that may not exist • the Amazonian language last spoken by a parrot • the Caucasian language with no vowels • a South Asian language whose innumerable verbs include gobray (to fall into a well unknowingly) and onsra (to love for the last time). Abley also highlights languages that can be found closer to home: Yiddish in Brooklyn and Montreal, Yuchi in Oklahoma, and Mohawk in New York and Quebec. -

Kanien'keha / Mohawk Indigenous Language

Kanien’keha / Mohawk Indigenous Language Revitalisation Efforts KANIEN’KEHA / MOHAWK INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE REVITALISATION EFFORTS IN CANADA GRACE A. GOMASHIE University of Western Ontario ABSTRACT. This paper gives an overview of ongoing revitalisation efforts for Kanien’keha / Mohawk, one of the endangered Indigenous languages in Canada. For the Mohawk people, their language represents a significant part of the culture, identity and well-being of individuals, families, and communities. The endanger- ment of Kanien’keha and other Indigenous languages in Canada was greatly accelerated by the residential school system. This paper describes the challenges surrounding language revitalisation in Mohawk communities within Canada as well as progress made, specifically for the Kanien’keha / Mohawk language. EFFORTS DE REVITALISATION LINGUISTIQUE DE LA LANGUE MOHAWK / KANIEN’KEHA AU CANADA RÉSUMÉ. Cet article offre une vue d’ensemble des efforts de revitalisation linguis- tique réalisés pour préserver la langue mohawk / kanien’keha, une des langues autochtones les plus menacées au Canada. Pour la communauté mohawk, cette langue constitue une part fondamentale de la culture, de l’identité et du bien-être des individus, des familles et des communautés. La mise en péril de la langue mohawk / kanien’keha et des autres langues autochtones au Canada a été grandement accentuée par le système de pensionnats autochtones. Cet article explore les défis inhérents à la revitalisation de la langue en cours dans les communautés mohawks au Canada et les progrès réalisés, particulièrement en ce qui a trait à la langue mohawk / kanien’keha. WHY SAVING ENDANGERED LANGUAGES IS IMPORTANT Linguists estimate that at least half of the world’s 7,000 languages will be endangered in a few generations as they are no longer being spoken as first languages (Austin & Sallabank, 2011; Krauss, 1992). -

Sign Language Endangerment and Linguistic Diversity Ben Braithwaite

RESEARCH REPORT Sign language endangerment and linguistic diversity Ben Braithwaite University of the West Indies at St. Augustine It has become increasingly clear that current threats to global linguistic diversity are not re - stricted to the loss of spoken languages. Signed languages are vulnerable to familiar patterns of language shift and the global spread of a few influential languages. But the ecologies of signed languages are also affected by genetics, social attitudes toward deafness, educational and public health policies, and a widespread modality chauvinism that views spoken languages as inherently superior or more desirable. This research report reviews what is known about sign language vi - tality and endangerment globally, and considers the responses from communities, governments, and linguists. It is striking how little attention has been paid to sign language vitality, endangerment, and re - vitalization, even as research on signed languages has occupied an increasingly prominent posi - tion in linguistic theory. It is time for linguists from a broader range of backgrounds to consider the causes, consequences, and appropriate responses to current threats to sign language diversity. In doing so, we must articulate more clearly the value of this diversity to the field of linguistics and the responsibilities the field has toward preserving it.* Keywords : language endangerment, language vitality, language documentation, signed languages 1. Introduction. Concerns about sign language endangerment are not new. Almost immediately after the invention of film, the US National Association of the Deaf began producing films to capture American Sign Language (ASL), motivated by a fear within the deaf community that their language was endangered (Schuchman 2004). -

Horatio Hale M.A

HORATIO HALE M.A. (Harvard), F.R.S.C. (1817-1896) BY WILLIAM N. FENTON "The Nestor of American Philologists" (MÜLLER) IT HAS BEEN THE good fortune of Iroquois studies that the field has attracted gifted minds. The pioneer work of Lewis H. Morgan of Rochester, N.Y., in ethnology was paralleled in linguistics by that of Horatio Hale of Clinton, Ontario. Both men were lawyers, both were attracted to Iroquois political organization, and each brought unique gifts to the recording of Indian life which reinforced the other's con- tribution: Morgan's work on kinship and on the structure of the confederacy was enhanced by Hale's gift with languages and his sense of poetry which he fulfilled so beautifully in The Iroquois Book of Rites. Some of the quality of the original Iroquois comes through in his Eng- lish rendering of the lament to the founders of the League (page 123): Hail, my grandsires! Now hearken while your grandchildren cry mournfully to you, —because the Great League which you established has grown old. Hail, my grandsires! You have said that Sad will be the fate of those who come in the latter times. Though not the founder of American linguistics, Hale was, after Gallatin, none the less, its most distinguished practi- tioner, and he came by these qualities naturally. viii WILLIAM N. FENTON Son of a distinguished New England literary family, Horatio Emmons Hale was born at Newport, N.H., on May 3, 1817. His father, David Hale, a lawyer of that town, died within five years, but his mother, Sarah Josepha Hale, who is credited with having authored "Mary Had a Little Lamb," was for nearly half a century editor of the Lady's Magazine (Boston), and afterward of Godey's Lady's Book (Philadelphia); she was a pioneer advocate of higher education for women, she was very active in the missionary movement, and her commitment to patriotic causes ex- tended from successfully raising funds for completion of the Bunker Hill Monument to petitioning presidents and governors to make Thanksgiving Day a national festival. -

The 5 Parameters of ASL Before You Begin Sign Language Partner Activities, You Need to Learn the 5 Parameters of ASL

The 5 Parameters of ASL Before you begin Sign Language Partner activities, you need to learn the 5 Parameters of ASL. You will use these parameters to describe new vocabulary words you will learn with your partner while completing Language Partner activities. Read and learn about the 5 Parameters below. DEFINITION In American Sign Language (ASL), we use the 5 Parameters of ASL to describe how a sign behaves within the signer’s space. The parameters are handshape, palm orientation, movement, location, and expression/non-manual signals. All five parameters must be performed correctly to sign the word accurately. Go to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FrkGrIiAoNE for a signed definition of the 5 Parameters of ASL. Don’t forget to turn the captions on if you are a beginning ASL student. Note: The signer’s space spans the width of your elbows when your hands are on your hips to the length four inches above your head to four inches below your belly button. Imagine a rectangle drawn around the top half of your body. TYPES OF HANDSHAPES Handshapes consist of the manual alphabet and other variations of handshapes. Refer to the picture below. TYPES OF ORIENTATIONS Orientation refers to which direction your palm is facing for a particular sign. The different directions are listed below. 1. Palm facing out 2. Palm facing in 3. Palm is horizontal 4. Palm faces left/right 5. Palm toward palm 6. Palm up/down TYPES OF MOVEMENT A sign can display different kinds of movement that are named below. 1. In a circle 2. -

Eyak Podcast Gr: 9-12 (Lesson 1)

HONORING EYAK: EYAK PODCAST GR: 9-12 (LESSON 1) Elder Quote: “We have a dictionary pertaining to the Eyak language, since there are so few of us left. That’s something my mom neve r taught me, was the Eyak language. It is altogether different than the Aleut. There are so few of us left that they have to do a book about the Eyak Tribe. There are so many things that my mother taught me, like smoking fish, putting up berries, and how to keep our wild meat. I have to show you; I can’t tell you how it is done, but anything you want to know I’ll tell you about the Eyak tribe.” - Rosie Lankard, 1980i Grade Level: 9-12 Overview: Heritage preservation requires both active participation and awareness of cultural origins. The assaults upon Eyak culture and loss of fluent Native speakers in the recent past have made the preservation of Eyak heritage even more challenging. Here students actively investigate and discuss Eyak history and culture to inspire their production of culturally insightful podcasts. Honoring Eyak Page 1 Cordova Boy in sealskin, Photo Courtesy of Cordova Historical Society Standards: AK Cultural: AK Content: CRCC: B1: Acquire insights from other Geography B1: Know that places L1: Students should understand the cultures without diminishing the integrity have distinctive characteristics value and importance of the Eyak of their own. language and be actively involved in its preservation. Lesson Goal: Students select themes or incidents from Eyak history and culture to create culturally meaningful podcasts. Lesson Objectives: Students will: Review and discuss Eyak history. -

Building BSL Signbank: the Lemma Dilemma Revisited

Fenlon, Jordan, Kearsy Cormier & Adam Schembri. in press. Building BSL SignBank: The lemma dilemma revisited. International Journal of Lexicography. (Pre-proof draft: March 2015. Check for updates before citing.) 1 Building BSL SignBank: The lemma dilemma revisited Abstract One key criterion when creating a representation of the lexicon of any language within a dictionary or lexical database is that it must be decided which groups of idiosyncratic and systematically modified variants together form a lexeme. Few researchers have, however, attempted to outline such principles as they might apply to sign languages. As a consequence, some sign language dictionaries and lexical databases appear to be mixed collections of phonetic, phonological, morphological, and lexical variants of lexical signs (e.g. Brien 1992) which have not addressed what may be termed as the lemma dilemma. In this paper, we outline the lemmatisation practices used in the creation of BSL SignBank (Fenlon et al. 2014a), a lexical database and dictionary of British Sign Language based on signs identified within the British Sign Language Corpus (http://www.bslcorpusproject.org). We argue that the principles outlined here should be considered in the creation of any sign language lexical database and ultimately any sign language dictionary and reference grammar. Keywords: lemma, lexeme, lemmatisation, sign language, dictionary, lexical database. 1 Introduction When one begins to document the lexicon of a language, it is necessary to establish what one considers to be a lexeme. Generally speaking, a lexeme can be defined as a unit that refers to a set of words in a language that bear a relation to one another in form and meaning. -

Life Long Learning Task Force

LIFE LONG LEARNING TASK FORCE Language & Culture Centre Vision & Five-Year Plan March 31, 2019 Onkwakara Communications & Consulting Inc. Life Long Learning Task Force FINAL REPORT Contract January to March 2019 INTRODUCTION & HISTORY At Six Nations there has been a second language program in Mohawk and Cayuga for more than 40 years. In Summer 1983 there was an opportunity to work with the Haudenosaunee second language teachers to help them to refine and re-develop their second language programs. During those meetings with the language teachers there was some discussion surrounding the fact that the students were not using the language to communicate, in fact, they were not using the language at all, which caused great distress among those first-language speaking teachers. It was around that time that immersion programs were beginning in Ontario for French language and our Haudenosaunee language teachers were very interested in how immersion worked and how well the student actually used their target language. With those questions in mind we began collecting information on how immersion in French was being taught and how well the students were communicating in the language. From those conversations a group of parents were brought together to discuss the possibility of an immersion program for Six Nations in both Mohawk and Cayuga. The parents who attended these meetings took steps to start an immersion program that very September. One immersion program was offered in Mohawk and another was offered in Cayuga, while the second language programs continued in the English- speaking elementary schools of the community. In the discussions with parents and language teachers it became apparent that without the language we would lose our culture and our identity and we would no longer be Haudenosaunee people and we would become just like everybody else in the province and that idea was unacceptable to virtually everyone in the community. -

Language Teaching and Learning Software For

Natural Language Generation for Polysynthetic Languages: Language Teaching and Learning Software for Kanyen’keha´ (Mohawk) Greg Lessard Nathan Brinklow Michael Levison School of Computing Department of Languages, School of Computing Queen’s University Literatures and Cultures Queen’s University Canada Queen’s University Canada [email protected] Canada [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Kanyen’keha´ (in English, Mohawk) is an Iroquoian language spoken primarily in Eastern Canada (Ontario, Quebec).´ Classified as endangered, it has only a small number of speakers and very few younger native speakers. Consequently, teachers and courses, teaching materials and software are urgently needed. In the case of software, the polysynthetic nature of Kanyen’keha´ means that the number of possible combinations grows exponentially and soon surpasses attempts to capture variant forms by hand. It is in this context that we describe an attempt to produce language teaching materials based on a generative approach. A natural language generation environment (ivi/Vinci) embedded in a web environment (VinciLingua) makes it possible to produce, by rule, variant forms of indefinite complexity. These may be used as models to explore, or as materials to which learners respond. Generated materials may take the form of written text, oral utterances, or images; responses may be typed on a keyboard, gestural (using a mouse) or, to a limited extent, oral. The software also provides complex orthographic, morphological and syntactic analysis of learner productions. We describe the trajectory of development of materials for a suite of four courses on Kanyen’keha,´ the first of which will be taught in the fall of 2018. -

A PDF Combined with Pdfmergex

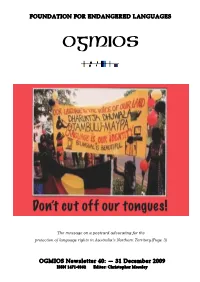

!"#$%&'("$)!"*)+$%&$,+*+%)-&$,#&,+.) ) OGMIOS The message on a postcard advocating for the protection of language rights in Australia’s Northern Territory (Page 3) ",/(".)$012304405)678)9):;)%0<0=>05)?77@) (..$);6A;B7:C?))))))+DE4F58)GH5E24FIH05)/F2030J) 2 DEBFD<'C4G"64$$4+'HI,'J'KL'=4/4M14+'NIIO' F<<C'LHPLQIKRN''''''()#$*+,'07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;' !""#"$%&$'()#$*+,'!)+#%&*'-+."/*$$' 0*&$+#1.$#&2'()#$*+",'3*24+'564&/78'9*"4:7'56;$748'<4+4&%'=>!2*"$#&*8'07+#"$*:74+'?%)@#46)8'A+%&/#"'B'?.6$8'' C#/7*6%"'D"$64+8'!&)+4%'3#$$4+' ' !"#$%&$'$()'*+,$"-'%$.' /012,3()+'14.' ' 07+#"$*:74+'B*"464;8' A*.&)%$#*&'@*+'(&)%&24+4)'X%&2.%24"8' O'S4"$)4&4'0+4"/4&$8' LPN'5%#61+**Y'X%&48'' 0%T4+"7%M'?4#27$"8' 5%$7'5!L'P!!8'(&26%&)' 34%)#&2'3EH'P?=8'(&26%&)' &*"$64+V/7#1/7%W)4M*&W/*W.Y'' /7+#"M*"464;UIV;%7**W/*M'' 'GGGW*2M#*"W*+2' The Austronesian Languages......................................... 19! LW'()#$*+#%6 3! Immersion – a film on endangered languages ............... 19! Cover Story: Northern Territory’s small languages sidelined from schools ...................................................... 3! RW'\6%/4"'$*'2*'*&'$74'S41 20! NW! =4T46*:M4&$'*@'$74'A*.&)%$#*& 4! Irish upside down............................................................ 20! Resolution of the FEL XIII Conference, Khorog, Tajikistan, OW'A*+$7/*M#&2'4T4&$" 21! 26, September, 2009 ........................................................ 4! HRELP Workshop: Endangered Languages, endangered FEL and UNESCO Atlas partnership................................ 4! knowledge & sustainability............................................. -

33 Contact and North American Languages

9781405175807_4_033 1/15/10 5:37 PM Page 673 33 Contact and North American Languages MARIANNE MITHUN Languages indigenous to the Americas offer some good opportunities for inves- tigating effects of contact in shaping grammar. Well over 2000 languages are known to have been spoken at the time of first contacts with Europeans. They are not a monolithic group: they fall into nearly 200 distinct genetic units. Yet against this backdrop of genetic diversity, waves of typological similarities suggest pervasive, longstanding multilingualism. Of particular interest are similarities of a type that might seem unborrowable, patterns of abstract structure without shared substance. The Americas do show the kinds of contact effects common elsewhere in the world. There are some strong linguistic areas, on the Northwest Coast, in California, in the Southeast, and in the Pueblo Southwest of North America; in Mesoamerica; and in Amazonia in South America (Bright 1973; Sherzer 1973; Haas 1976; Campbell, Kaufman, & Stark 1986; Thompson & Kinkade 1990; Silverstein 1996; Campbell 1997; Mithun 1999; Beck 2000; Aikhenvald 2002; Jany 2007). Numerous additional linguistic areas and subareas of varying sizes and strengths have also been identified. In some cases all domains of language have been affected by contact. In some, effects are primarily lexical. But in many, there is surprisingly little shared vocabulary in contrast with pervasive structural parallelism. The focus here will be on some especially deeply entrenched structures. It has often been noted that morphological structure is highly resistant to the influence of contact. Morphological similarities have even been proposed as better indicators of deep genetic relationship than the traditional comparative method.