In the Service of the Public Functions and Transformation of Media in Developing Countries Imprint

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I N H a L T S V E R Z E I C H N

SWR BETEILIGUNGSBERICHT 2018 Beteiligungsübersicht 2018 Südwestrundfunk 100% Tochtergesellschaften Beteiligungsgesellschaften ARD/ZDF Beteiligungen SWR Stiftungen 33,33% Schwetzinger SWR Festspiele 49,00% MFG Medien- und Filmgesellschaft 25,00% Verwertungsgesellschaft der Experimentalstudio des SWR e.V. gGmbH, Schwetzingen BaWü mbH, Stuttgart Film- u. Fernsehproduzenten mbH Baden-Baden 45,00% Digital Radio Südwest GmbH 14,60% ARD/ZDF-Medienakademie Stiftung Stuttgart gGmbH, Nürnberg Deutsches Rundfunkarchiv Frankfurt 16,67% Bavaria Film GmbH 11,43% IRT Institut für Rundfunk-Technik Stiftung München GmbH, München Hans-Bausch-Media-Preis 11,11% ARD-Werbung SALES & SERV. GmbH 11,11% Degeto Film GmbH Frankfurt München 0,88% AGF Videoforschung GmbH 8,38% ARTE Deutschland TV GmbH Frankfurt Baden-Baden Mitglied Haus des Dokumentarfilms 5,56% SportA Sportrechte- u. Marketing- Europ. Medienforum Stgt. e. V. agentur GmbH, München Stammkapital der Vereinsbeiträge 0,98% AGF Videoforschung GmbH Frankfurt Finanzverwaltung, Controlling, Steuerung und weitere Dienstleistungen durch die SWR Media Services GmbH SWR Media Services GmbH Stammdaten I. Name III. Rechtsform SWR Media Services GmbH GmbH Sitz Stuttgart IV. Stammkapital in Euro 3.100.000 II. Anschrift V. Unternehmenszweck Standort Stuttgart - die Produktion und der Vertrieb von Rundfunk- Straße Neckarstraße 230 sendungen, die Entwicklung, Produktion und PLZ 70190 Vermarktung von Werbeeinschaltungen, Ort Stuttgart - Onlineverwertungen, Telefon (07 11) 9 29 - 0 - die Beschaffung, Produktion und Verwertung -

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020

Facts and Figures 2020 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF (Zweites Deutsches Fern German channels PHOENIX and sehen) is Germany’s national KiKA, and the European chan public television. It is run as an nels 3sat and ARTE. independent nonprofit corpo ration under the authority of The corporation has a permanent the Länder, the sixteen states staff of 3,600 plus a similar number that constitute the Federal of freelancers. Since March 2012, Republic of Germany. ZDF has been headed by Direc torGeneral Thomas Bellut. He The nationwide channel ZDF was elected by the 60member has been broadcasting since governing body, the ZDF Tele 1st April 1963 and remains one vision Council, which represents of the country’s leading sources the interests of the general pub of information. Today, ZDF lic. Part of its role is to establish also operates the two thematic and monitor programme stand channels ZDFneo and ZDFinfo. ards. Responsibility for corporate In partnership with other pub guide lines and budget control lic media, ZDF jointly operates lies with the 14member ZDF the internetonly offer funk, the Administrative Council. ZDF’s head office in Mainz near Frankfurt on the Main with its studio complex including the digital news studio and facilities for live events. Seite 2 ZDF German Television | Facts and Figures 2020 Facts about ZDF ZDF is based in Mainz, but also ZDF offers fullrange generalist maintains permanent bureaus in programming with a mix of the 16 Länder capitals as well information, education, arts, as special editorial and production entertainment and sports. -

Schumacher, Frederike Die Causa Brender

Fachbereich Medien Schumacher, Frederike Die Causa Brender - Einschränkungen der Rundfunkfreiheit im ZDF- Staatsvertrag durch Zusammensetzung und Befugnisse des Verwaltungsrats. - Bachelorarbeit - Hochschule Mittweida (FH) – University of Applied Sciences Hamburg - 2010 Fachbereich Medien Schumacher, Frederike Die Causa Brender - Einschränkungen der Rundfunkfreiheit im ZDF- Staatsvertrag durch Zusammensetzung und Befugnisse des Verwaltungsrats. The Causa Brender Limitations of freedom of boadcasting in the ZDF-Staatsvertrag* due to constitution and power of the administrative board. * ZDF-treaty: a legal framework for the german public broadcasting service ZDF. - eingereicht als Bachelorarbeit- Hochschule Mittweida (FH) – University of Applied Sciences Erstprüfer Zweitprüfer Prof. Dr. phil Otto Altendorfer Heidrun Köhlert Hamburg- 2010 Schumacher, Frederike: Die Causa Brender - Einschränkungen der Rundfunkfreiheit im ZDF-Staats- vertrag durch Zusammensetzung und Befugnisse des Verwaltungsrats. – 2010- 79 S. Mittweida, Hochschule (FH), Fachbereich Medien, Bachelorarbeit Referat Diese Bachelorarbeit beschäftigt sich mit der Übersetzung des Begriffs der Rund- funkfreiheit im ZDF-Staatsvertrag. Sie untersucht, ob die Grundsätze dieser Rundfunkfreiheit, wie sie durch das Ver- fassungsgericht in seinen Fernsehurteilen und darüber hinaus definiert wurden, hierin ausreichend berücksichtigt werden, und sie zeigt wo die Rundfunkfreiheit Einschränkungen erfährt. Anstoß zu der Fragestellung gaben die Entwicklungen und Entscheidungen, die der Abwahl -

In the Service of the Public Functions and Transformation of Media in Developing Countries Imprint Publisher Deutsche Welle 53110 Bonn, Germany

Edition dW AkAdEmiE #02/2014 mEdiA dEvElopmEnt In the Service of the Public Functions and Transformation of Media in Developing Countries Imprint pUBliSHER Deutsche Welle 53110 Bonn, Germany RESponSiBlE Christian Gramsch AUtHoRS Erik Albrecht Cletus Gregor Barié Petra Berner Priya Esselborn Richard Fuchs Lina Hartwieg Jan Lublinski Laura Schneider Achim Toennes Merjam Wakili Jackie Wilson-Bakare EditoRS Jan Lublinski Merjam Wakili Petra Berner dESiGn Programming / Design pRintEd November 2014 © DW Akademie Edition dW AkAdEmiE #02/2014 mEdiA dEvElopmEnt In the Service of the Public Functions and Transformation of Media in Developing Countries Jan Lublinski, Merjam Wakili, Petra Berner (eds.) Table of Contents Preface 4 04 Kyrgyzstan: Advancements in Executive Summary 6 a Media-Friendly Environment 52 Jackie Wilson-Bakare Part I: Developing Public Service Media – Kyrgyzstan – A Brief Overview 53 Functions and Change Processes Media Landscape 54 Obschestvennaya Tele-Radio Kompaniya (OTRK) 55 01 Introduction: A Major Challenge for Stakeholders in the Transformation Process 56 Media Development 10 Status of the Media Organization 56 Jan Lublinski, Merjam Wakili, Petra Berner Public Service: General Functions 61 Public Service Broadcasting – West European Roots, Achievements and Challenges 62 International Ambitions 12 Transformation Approaches 63 Lessons Learned? – Transformations Since the 1990s 14 Appendix 72 Reconsidering Audiences – Media in the Information Society 15 05 Namibia: Multilingual Content and the Need Approach and Aim of the -

Öffentlich-Rechtlicher Rundfunk in Der Krise

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Beck, Hanno; Beyer, Andrea Article — Published Version Öffentlich-rechtlicher Rundfunk in der Krise Wirtschaftsdienst Suggested Citation: Beck, Hanno; Beyer, Andrea (2013) : Öffentlich-rechtlicher Rundfunk in der Krise, Wirtschaftsdienst, ISSN 1613-978X, Springer, Heidelberg, Vol. 93, Iss. 3, pp. 175-181, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10273-013-1505-5 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/110293 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu DOI: 10.1007/s10273-013-1505-5 Analysen und Berichte Rundfunkpolitik Hanno Beck, Andrea Beyer Öffentlich-rechtlicher Rundfunk in der Krise Diverse Skandale haben die öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten in Misskredit gebracht. Dies hat erneut die Diskussion entfacht, ob der Rundfunk überhaupt in öffentlicher Hand produziert werden sollte. -

Yangon University of Economics Department of Commerce Master of Accounting Programme the Effect of Leadership Styles on Organiza

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE MASTER OF ACCOUNTING PROGRAMME THE EFFECT OF LEADERSHIP STYLES ON ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT IN MEDIA AND ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY THWE THWE THANT NOVEMBER, 2019 The Effect of Leadership Styles on Organi zational Commitment in Media and Entertainment Industry The Research Paper is submitted to the Board of Examiners in partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Degree of Master of Accounting Supervised by: Submitted by: Daw Htay Htay Ma Thwe Thwe Thant Associate Professor M.Act. II – 2 Department of Commerce Master of Accounting (2018-2019) Yangon University of Economics Yangon University of Economics ACCEPTANCE Accepted by the Board of Examiners of the Department of Commerce, Yangon University of Economics, in partial fulfillment for the requirements of the Master Degree, Master of Accounting. BOARD OF EXAMINERS ------------------------------------ Dr. Tin Win (Chairman) Rector Yangon University of Economics ------------------------------------- ------------------------------- (Supervisor) (Chief Examiner) Daw Htay Htay Dr. Soe Thu Associate Professor Professor and Head Department of Commerce Department of Commerce Yangon University of Economics Yangon University of Economics ----------------------------------- ------------------------------- (Examiner) (External Examiner) Dr. Tin Tin Htwe Daw Kyi Kyi Sein Professor Professor (Retired) Department of Commerce Department of Commerce Yangon University of Economics Yangon University of Economics --------------------------------- ------------------------------- -

BACHELORARBEIT Die Causa Nikolaus Brender Und Die Politische

BACHELORARBEIT Frau Angelina Niederprüm Die Causa Nikolaus Brender und die politische Intervention in den öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten Eine Untersuchung der Berichterstattung regionaler und überregionaler Zeitungen und Zeitschriften 2015 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Die Causa Nikolaus Brender und die politische Intervention in den öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten Eine Untersuchung der Berichterstattung regionaler und überregionaler Zeitungen und Zeitschriften. Autorin: Frau Angelina Niederprüm Studiengang: Angewandte Medien Seminargruppe: AM11wJ1-B Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr. phil. Otto Altendorfer Zweitprüfer: Dipl. Sportwissenschaftler Holger Tromp Einreichung: Bad Rappenau, 23.01.2015 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS The Case of Nikolaus Brender and the political intervention in public broadcasting. A study about the coverage in regional and national newspapers and magazines. author: Ms. Angelina Niederprüm course of studies: applied media seminar group: AM11wJ1-B first examiner: Prof. Dr. phil. Otto Altendorfer second examiner: Qualified Sports-Academic Holger Tromp submission: Bad Rappenau, 23.01.2015 Bibliografische Angaben VI Bibliografische Angaben Niederprüm, Angelina: Die Causa Nikolaus Brender und die politische Intervention in den öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunkanstalten. Eine Untersuchung der Berichterstattung regionaler und überregi- onaler Zeitungen und Zeitschriften. The case of Nikolaus Brender and the political intervention in public broadcasting. A study about the coverage in regional and national newspapers -

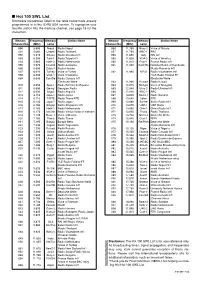

Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave Frequencies Listed in the Table Below Have Already Programmed in to the IC-R5 USA Version

I Hot 100 SWL List Shortwave frequencies listed in the table below have already programmed in to the IC-R5 USA version. To reprogram your favorite station into the memory channel, see page 16 for the instruction. Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Memory Frequency Memory Station Name Channel No. (MHz) name Channel No. (MHz) name 000 5.005 Nepal Radio Nepal 056 11.750 Russ-2 Voice of Russia 001 5.060 Uzbeki Radio Tashkent 057 11.765 BBC-1 BBC 002 5.915 Slovak Radio Slovakia Int’l 058 11.800 Italy RAI Int’l 003 5.950 Taiw-1 Radio Taipei Int’l 059 11.825 VOA-3 Voice of America 004 5.965 Neth-3 Radio Netherlands 060 11.910 Fran-1 France Radio Int’l 005 5.975 Columb Radio Autentica 061 11.940 Cam/Ro National Radio of Cambodia 006 6.000 Cuba-1 Radio Havana /Radio Romania Int’l 007 6.020 Turkey Voice of Turkey 062 11.985 B/F/G Radio Vlaanderen Int’l 008 6.035 VOA-1 Voice of America /YLE Radio Finland FF 009 6.040 Can/Ge Radio Canada Int’l /Deutsche Welle /Deutsche Welle 063 11.990 Kuwait Radio Kuwait 010 6.055 Spai-1 Radio Exterior de Espana 064 12.015 Mongol Voice of Mongolia 011 6.080 Georgi Georgian Radio 065 12.040 Ukra-2 Radio Ukraine Int’l 012 6.090 Anguil Radio Anguilla 066 12.095 BBC-2 BBC 013 6.110 Japa-1 Radio Japan 067 13.625 Swed-1 Radio Sweden 014 6.115 Ti/RTE Radio Tirana/RTE 068 13.640 Irelan RTE 015 6.145 Japa-2 Radio Japan 069 13.660 Switze Swiss Radio Int’l 016 6.150 Singap Radio Singapore Int’l 070 13.675 UAE-1 UAE Radio 017 6.165 Neth-1 Radio Netherlands 071 13.680 Chin-1 China Radio Int’l 018 6.175 Ma/Vie Radio Vilnius/Voice -

Lara Marie Müller

Lara Marie M¨uller Doctoral Candidate Contact Information Email: [email protected] Phone: +49 151 651 050 44 Academic Education PhD in Economics since 2020 University of Cologne, Cologne Graduate School of Economics Research Interest: Media Economics and Economics of Digitization Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Johannes M¨unster,Prof. Dr. Bettina Rockenbach Double Degree: Master in Economics 2018 - 2020 University of Cologne, Germany (M.Sc.) and Keio University, Japan (M.A.) One year of studies at each institution Bachelor of Science in Economics 2014 - 2018 University of Cologne Including two exchange semesters: - Warsaw School of Economics, Poland (SS2016) - Pontif´ıciaUniversidade Cat´olicado Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (WS2015/16) Research Interest I am interested in how we can design media markets that best serve society. For this, I aim to conduct mainly experimental research to gain insights on Welfare effects on digital media markets, for example in the context of personalisation or misinformation. Professional Experience Research Associate since 07/2020 Chair of Media Economics, Prof. Dr. Johannes M¨unster,University of Cologne Teaching: Exercise in Media Economics (Bachelor and Master), Seminar on Media Mar- kets (Bachelor), Supervision of Bachelor Theses Freelance Journalist 2018 - 2020 Covering mainly economics for German news outlets, magazines and broadcasters. Cus- tomers included: Handelsblatt, Welt am Sonntag, ada, Die Welt, WDR, FAZ.net, Frank- furter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung, among others. Lecturer at K¨olnerJournalistenschule -

Download This PDF File

internet resources John H. Barnett Global voices, global visions International radio and television broadcasts via the Web he world is calling—are you listening? used international broadcasting as a method of THere’s how . Internet radio and tele communicating news and competing ideologies vision—tuning into information, feature, during the Cold War. and cultural programs broadcast via the In more recent times, a number of reli Web—piqued the interest of some educators, gious broadcasters have appeared on short librarians, and instructional technologists in wave radio to communicate and evangelize the 1990s. A decade ago we were still in the to an international audience. Many of these early days of multimedia content on the Web. media outlets now share their programming Then, concerns expressed in the professional and their messages free through the Internet, literature centered on issues of licensing, as well as through shortwave radio, cable copyright, and workable business models.1 television, and podcasts. In my experiences as a reference librar This article will help you find your way ian and modern languages selector trying to to some of the key sources for freely avail make Internet radio available to faculty and able international Internet radio and TV students, there were also information tech programming, focusing primarily on major nology concerns over bandwidth usage and broadcasters from outside the United States, audio quality during that era. which provide regular transmissions in What a difference a decade makes. Now English. Nonetheless, one of the benefi ts of with the rise of podcasting, interest in Web tuning into Internet radio and TV is to gain radio and TV programming has recently seen access to news and knowledge of perspec resurgence. -

Der Fall Brender Und Die Aufsicht Über Den Öffentlich-Rechtlichen Rundfunk Karlsruher Dialog Zum Informationsrecht Band 1

Karlsruher Dialog zum Informationsrecht Karlsruher Institut für Technologie Band 1 Zentrum für Angewandte Rechtswissenschaft ZAR Indra Spiecker gen. Döhmann (Hrsg.) Prof. Dr. iur. Indra Spiecker gen. Döhmann, LL.M. (Georgetown), ist Direktorin des Instituts für Informations- und Wirtschaftsrecht am Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT). Der „Karlsruher Dialog zum Informationsrecht“ ist eine Vortragsreihe des Instituts für Informations- und Wirtschaftsrecht am Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT). Diese richtet sich an Wissenschaft, Wirtschaft und Praxis gleichermaßen. Sie bietet ein Forum für den Austausch über aktuelle recht- Christian Kirchberg liche Problemstellungen, aber auch Grundsatzfragen aus allen Bereichen des Informationsrechts. Mit der gleichnamigen Schriftenreihe wird den Vortragenden Gelegenheit gegeben, ihren Vortrag und die Erkenntnisse der anschließenden Diskussion Der Fall Brender und in einer erweiterten Fassung zu veröffentlichen. die Aufsicht über den Der Autor öffentlich-rechtlichen Rundfunk Prof. Dr. jur. Christian Kirchberg ist Rechtsanwalt in Karlsruhe und Honorarprofessor am Karlsruher Institut für Technologie (KIT). Der Verwaltungsrat des ZDF hat 2009 eine Vertragsverlängerung des Chef- redakteurs abgelehnt. Aufgrund des dadurch ausgelösten Streits über die Staatsfreiheit des Rundfunks und die vom Bundesverfassungsgericht ge- forderte Vertretung der „maßgeblichen gesellschaftlichen Kräfte” in den Rundfunkgremien wird der ZDF-Staatsvertrag nun vom höchsten deutschen Gericht überprüft. Die Schrift beleuchtet -

2010 Annual Language Service Review Briefing Book

Broadcasting Board of Governors 2010 Annual Language Service Review Briefing Book Broadcasting Board of Governors Table of Contents Acknowledgments............................................................................................................................................................................................3 Preface ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................5 How to Use This Book .................................................................................................................................................................................6 Albanian .................................................................................................................................................................................................................12 Albanian to Kosovo ......................................................................................................................................................................................14 Arabic .......................................................................................................................................................................................................................16 Armenian ...............................................................................................................................................................................................................20