Holmberg-Dissertation-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Role of Cú Chulainn in Old and Middle Irish Narrative Literature with Particular Reference to Tales Belonging to the Ulster Cycle

The role of Cú Chulainn in Old and Middle Irish narrative literature with particular reference to tales belonging to the Ulster Cycle. Mary Leenane, B.A. 2 Volumes Vol. 1 Ph.D. Degree NUI Maynooth School of Celtic Studies Faculty of Arts, Celtic Studies and Philosophy Head of School: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn Supervisor: An tOllamh Ruairí Ó hUiginn June 2014 Table of Contents Volume 1 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I: General Introduction…………………………………………………2 I.1. Ulster Cycle material………………………………………………………...…2 I.2. Modern scholarship…………………………………………………………...11 I.3. Methodologies………………………………………………………………...14 I.4. International heroic biography………………………………………………..17 Chapter II: Sources……………………………………………………………...23 II.1. Category A: Texts in which Cú Chulainn plays a significant role…………...23 II.2. Category B: Texts in which Cú Chulainn plays a more limited role………...41 II.3. Category C: Texts in which Cú Chulainn makes a very minor appearance or where reference is made to him…………………………………………………...45 II.4. Category D: The tales in which Cú Chulainn does not feature………………50 Chapter III: Cú Chulainn’s heroic biography…………………………………53 III.1. Cú Chulainn’s conception and birth………………………………………...54 III.1.1. De Vries’ schema………………...……………………………………………………54 III.1.2. Relevant research to date…………………………………………………………...…55 III.1.3. Discussion and analysis…………………………………………………………...…..58 III.2. Cú Chulainn’s youth………………………………………………………...68 III.2.1 De Vries’ schema………………………………………………………………………68 III.2.2 Relevant research to date………………………………………………………………69 III.2.3 Discussion and analysis………………………………………………………………..78 III.3. Cú Chulainn’s wins a maiden……………………………………………….90 III.3.1 De Vries’ schema………………………………………………………………………90 III.3.2 Relevant research to date………………………………………………………………91 III.3.3 Discussion and analysis………………………………………………………………..95 III.3.4 Further comment……………………………………………………………………...108 III.4. -

Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, Vol.117C, Pp.65-99

Gleeson P. (2017) Luigne Breg and the Origins of the Uí Néill. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy: Archaeology, Culture, History, Literature, vol.117C, pp.65-99. Copyright: This is the author’s accepted manuscript of an article that has been published in its final definitive form by the Royal Irish Academy, 2017. Link to article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3318/priac.2017.117.04 Date deposited: 07/04/2017 Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Luigne Breg and the origins of the Uí Néill By Patrick Gleeson, School of History, Classics and Archaeology, Newcastle University Email: [email protected] Phone: (+44) 01912086490 Abstract: This paper explores the enigmatic kingdom of Luigne Breg, and through that prism the origins and nature of the Uí Néill. Its principle aim is to engage with recent revisionist accounts of the various dynasties within the Uí Néill; these necessitate a radical reappraisal of our understanding of their origins and genesis as a dynastic confederacy, as well as the geo-political landsape of the central midlands. Consequently, this paper argues that there is a pressing need to address such issues via more focused analyses of local kingdoms and political landscapes. Holistic understandings of polities like Luigne Breg are fundamental to framing new analyses of the genesis of the Uí Néill based upon interdisciplinary assessments of landscape, archaeology and documentary sources. In the latter part of the paper, an attempt is made to to initiate a wider discussion regarding the nature of kingdoms and collective identities in early medieval Ireland in relation to other other regions of northwestern Europe. -

The Death-Tales of the Ulster Heroes

ffVJU*S )UjfáZt ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY TODD LECTURE SERIES VOLUME XIV KUNO MEYER, Ph.D. THE DEATH-TALES OF THE ULSTER HEROES DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS, & CO. LTD. LONDON: WILLIAMS & NORGATE 1906 (Reprinted 1937) cJ&íc+u. Ity* rs** "** ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY TODD LECTURE SERIES VOLUME XIV. KUNO MEYER THE DEATH-TALES OF THE ULSTER HEROES DUBLIN HODGES, FIGGIS, & CO., Ltd, LONDON : WILLIAMS & NORGATE 1906 °* s^ B ^N Made and Printed by the Replika Process in Great Britain by PERCY LUND, HUMPHRIES &f CO. LTD. 1 2 Bedford Square, London, W.C. i and at Bradford CONTENTS PAGE Peeface, ....... v-vii I. The Death of Conchobar, 2 II. The Death of Lóegaire Búadach . 22 III. The Death of Celtchar mac Uthechaib, 24 IV. The Death of Fergus mac Róich, . 32 V. The Death of Cet mac Magach, 36 Notes, ........ 48 Index Nominum, . ... 46 Index Locorum, . 47 Glossary, ....... 48 PREFACE It is a remarkable accident that, except in one instance, so very- few copies of the death-tales of the chief warriors attached to King Conchobar's court at Emain Macha should have come down to us. Indeed, if it were not for one comparatively late manu- script now preserved outside Ireland, in the Advocates' Library, Edinburgh, we should have to rely for our knowledge of most of these stories almost entirely on Keating's History of Ireland. Under these circumstances it has seemed to me that I could hardly render a better service to Irish studies than to preserve these stories, by transcribing and publishing them, from the accidents and the natural decay to which they are exposed as long as they exist in a single manuscript copy only. -

Stories from Early Irish History

1 ^EUNIVERJ//, ^:IOS- =s & oo 30 r>ETRr>p'S LAMENT. A Land of Heroes Stories from Early Irish History BY W. LORCAN O'BYRNE WITH SIX ILLUSTRATIONS BY JOHN E. BACON BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED LONDON GLASGOW AND DUBLIN n.-a INTEODUCTION. Who the authors of these Tales were is unknown. It is generally accepted that what we now possess is the growth of family or tribal histories, which, from being transmitted down, from generation to generation, give us fair accounts of actual events. The Tales that are here given are only a few out of very many hundreds embedded in the vast quantity of Old Gaelic manuscripts hidden away in the libraries of nearly all the countries of Europe, as well as those that are treasured in the Royal Irish Academy and Trinity College, Dublin. An idea of the extent of these manuscripts may be gained by the statement of one, who perhaps had the fullest knowledge of them the late Professor O'Curry, in which he says that the portion of them (so far as they have been examined) relating to His- torical Tales would extend to upwards of 4000 pages of large size. This great mass is nearly all untrans- lated, but all the Tales that are given in this volume have already appeared in English, either in The Publications of the Society for the Preservation of the Irish Language] the poetical versions of The IV A LAND OF HEROES. Foray of Queen Meave, by Aubrey de Vere; Deirdre', by Dr. Robert Joyce; The Lays of the Western Gael, and The Lays of the Red Branch, by Sir Samuel Ferguson; or in the prose collection by Dr. -

Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung As a Junction Within Lebor Gabála Érenn

Edinburgh Research Explorer Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn Citation for published version: Thanisch, E 2013, Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor Gabála Érenn. in Quaestio Insularis: Selected Proceedings of the Cambridge Colloquium in Anglo-Saxon Norse and Celtic. vol. 13, pp. 69-93. <http://www.asnc.cam.ac.uk/publications/quaestio/Quaestio2012.html> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Quaestio Insularis General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Flann Mainistrech's Götterdämmerung as a Junction within Lebor 1 Gabála Érenn INTRODUCTION Lebor Gabála Érenn: Content Lebor Gabála Érenn (‘the Book of the Invasion of Ireland’) is the conventional title for a lengthy Irish pseudo-historical text extant in multiple recensions probably compiled during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.2 The text comprises a history of the Gaídil (‘Gaels’) within the context of a universal history derived from the Bible and from Classical historiography.3 Lebor Gabála traces the ancestry of the Gaídil back to Noah and follows their tortuous migrations, spanning many generations, from the Tower of Babel to Ireland via Spain. -

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. the Text

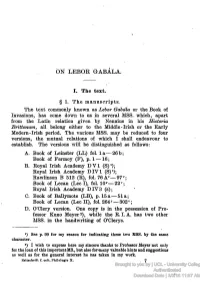

ON LEBOR GABALA. I. The text. § 1. The manuscripts. The text commonly known as Lebor Gabala or the Book of Invasions, has come down to us in several MSS. which, apart from the Latin relation given by Nennius in his Historia Brittomim, all belong either to the Middle-Irish or the Early Modern-Irish period. The various MSS. may be reduced to four versions, the mutual relations of which I shall endeavour to establish. The versions will be distinguished as follows: A. Book of Leinster (LL) fol. la—26b; Book of Fermoy (F), p. 1 —16; B. Royal Irish Academy DVI (S)1); Royal Irish Academy DIV1 (S)1); Rawlinson B 512 (R), fol. 76 Av— 97v; Book of Lecan (Lee I), fol. 10r—22v; Royal Irish Academy DIV3 (s); C. Book of Ballymote (LB), p. 15a—51 a; Book of Lecan (Lee H), fol. 264r—302v; D. OOlery version. One copy is in the possession of Pro- fessor Kuno Meyer2), while the R.I. A. has two other MSS. in the handwriting of O'Clerys. *) See p. 99 for my reason for indicating these two MSS. by the same character. 2) I wish to express here my sincere thanks to Professor Meyer not only for the loan of this important MS., but also formany valuable hints and suggestions as well as for the general interest he has taken in my work. Zeitschrift f. celt. Philologie X. 7 Brought to you by | UCL - University College London Authenticated Download Date | 3/3/16 11:57 AM OS A. G. VAN HAMEL, § 2. -

The Dagda As Briugu in Cath Maige Tuired

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2012-05 Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Martin, Scott A. https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/138967 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository Following a Fork in the Text: the Dagda as briugu in Cath Maige Tuired Scott A. Martin, May 2012 The description of the Dagda in §93 of Cath Maige Tuired has become iconic: the giant, slovenly man in a too-short tunic and crude horsehide shoes, dragging a huge club behind him. Several aspects of this depiction are unique to this text, including the language used to describe the Dagda’s odd weapon. The text presents it as a gabol gicca rothach, which Gray translates as a “wheeled fork.” In every other mention of the Dagda’s club – including the other references in CMT (§93 and §119) – the term used is lorg. DIL gives significantly different fields of reference for the two terms: 2 lorg denotes a staff, rod, club, handle of an implement, or “the membrum virile” (thus enabling the scatological pun Slicht Loirge an Dagdai, “Track of the Dagda’s Club/Penis”), while gabul bears a variety of definitions generally attached to the concept of “forking.” The attested compounds for gabul include gabulgicce, “a pronged pole,” with references to both the CMT usage and staves held by Conaire’s swineherds in Togail Bruidne Da Derga. DIL also mentions several occurrences of gabullorc, “a forked or pronged pole or staff,” including an occurrence in TBDD (where an iron gabullorg is carried by the supernatural Fer Caille) and another in Bretha im Fuillema Gell (“Judgements on Pledge-Interests”). -

Nomination of the Monastic City of Clonmacnoise and Its Cultural Landscape for Inclusion in the WORLD HERITAGE LIST

DRAFT Nomination of The Monastic City of Clonmacnoise and its Cultural Landscape For inclusion in the WORLD HERITAGE LIST Clonmacnoise World Heritage Site Draft Nomination Form Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................III 1. IDENTIFICATION OF THE PROPERTY ......................................................................1 1.a Country:..................................................................................................1 1.b State, Province or Region:......................................................................1 1.c Name of Property: ..................................................................................1 1.d Geographical co-ordinates to the nearest second ..................................1 1.e Maps and plans, showing the boundaries of the nominated property and buffer zone ........................................................................................................2 1.f Area of nominated property (ha.) and proposed buffer zone (ha.)..........3 2. DESCRIPTION..............................................................................................................4 2.a Description of Property ..........................................................................4 2.b History and development......................................................................31 3. JUSTIFICATION FOR INSCRIPTION ........................................................................38 3.a Criteria under which inscription -

Literature and Learning in Early Medieval Meath

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title Literature and learning in early medieval Meath Author(s) Downey, Clodagh Publication Date 2015 Downey, Clodagh (2015) 'Literature and Learning in Early Publication Medieval Meath' In: Crampsie, A., and Ludlow, F(Eds.). Information Meath History and Society: Interdisciplinary Essays on the History of an Irish County. Dublin : Geography Publications. Publisher Geography Publications Link to publisher's http://www.geographypublications.com/product/meath-history- version society/ Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/7121 Downloaded 2021-09-26T15:35:58Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. CHAPTER 04 - Clodagh Downey 7/20/15 1:11 PM Page 1 CHAPTER 4 Literature and learning in early medieval Meath CLODAGH DOWNEY The medieval literature of Ireland stands out among the vernacular literatures of western Europe for its volume, its diversity and its antiquity, and within this treasury of cultural riches, Meath holds a prominence greatly disproportionate to its geographical extent, however that extent is reckoned. Indeed, the first decision confronting anyone who wishes to consider this subject is to define its geographical limits: the modern county of Meath is quite a different entity to the medieval kingdom of Mide from which it gets its name and which itself designated different areas at different times. It would be quite defensible to include in a survey of medieval literature those areas which are now under the administration of other modern counties, but which may have been part of the medieval kingdom at the time that that literature was produced. -

ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context

Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080 the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:42029623 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context A dissertation presented by Gregory Dar!in to The Department of Celti# Literatures and Languages in partial fulfillment of the re%$irements for the degree of octor of Philosophy in the subje#t of Celti# Languages and Literatures (arvard University Cambridge+ Massa#husetts April 2019 / 2019 Gregory Darwin All rights reserved iii issertation Advisor: Professor Joseph Falaky Nagy Gregory Dar!in Mar gur dream Sí iad atá ag mairiúint fén bhfarraige: ML 4080 The Seal Woman in its Irish and International Context4 Abstract This dissertation is a study of the migratory supernatural legend ML 4080 “The Mermaid Legend” The story is first attested at the end of the eighteenth century+ and hundreds of versions of the legend have been colle#ted throughout the nineteenth and t!entieth centuries in Ireland, S#otland, the Isle of Man, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, Norway, S!eden, and Denmark. -

The Cath Maige Tuired and the Vǫluspá

Connections: the Cath Maige Tuired and the Vǫluspá Convergence of cultures, history and myth Angelina Kjerstad Johansen Master's Thesis History of Religion UNIVERSITY OF OSLO Autumn 2015 1 Copyright Angelina Kjerstad Johansen 2015 Connections: the Cath Maige Tuired and the Vǫluspá – Convergence of cultures, history and myth Angelina Kjerstad Johansen http://www.duo.uio.no Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo 2 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, Jens Braarvig, for having the patience to deal with me and my strange ways of doing things. Thank you to Jan Erik Rekdal and Karl Johansson for giving me the idea for this thesis and to my fellow students for great discussions. To all my friends and my amazing family, you know who you are, I love you more and more each day. And to the artists and musicians that make my life bearable, you do not know who you are, but without you I would truly go insane. A special thanks goes to my sister, Monica, for being my co-conspirator and for helping me bore every other member of our family with our academic discussions. May we continue to do so in the future! To Rita, whom I miss beyond words. I dedicate all my triumphs to you 4 5 Introduction The topic of the thesis is the Irish myth Cath Maige Tuired - "The Second Battle of Mag Tuired", which is the story about the battle between the Túatha Dé Danann, the gods of pagan Ireland, and their enemies the Fomoire. What I wish to focus upon in the Cath Maige Tuired is not the battle in itself, which has been compared to the war between the Aesir and the Vanir in Scandinavian mythology1, but a passage at the end of this myth, where the goddess Mórrigan (here in the form of a mortal) comes with a prediction of the end of the world. -

Order of Celtic Wolves Lesson 5

ORDER OF CELTIC WOLVES LESSON 5 Introduction Welcome to the fifth lesson. You are now over a third of your way into the lessons. This lesson has took quite a bit longer than I anticipated to come together. I apologise for this, but whilst putting research together, we want the OCW to be as accurate as possible. One thing that I often struggle with is whether ancient Druids used elements in their rituals. I know modern Druids use elements and directions, and indeed I have used them as part of ritual with my own Grove and witnessed varieties in others. When researching, you do come across different viewpoints and interpretations. All of these are valid, but sometimes it is good to involve other viewpoints. Thus, I am grateful for our Irish expert and interpreter, Sean Twomey, for his input and much of this topic is written by him. We endeavour to cover all the basics in our lessons. However, there will be some topics that interest you more than others. This is natural and when you find something that sparks your interest, then I recommend further study into whatever draws you. No one knows everything, but having an overview is a great starting point in any spiritual journey. That said, I am quite proud of the in-depth topics we have put together, especially on Ogham. You also learn far more from doing exercises than any amount of reading. Head knowledge without application is like having a medical consultation and ignoring specialist advice. In this lesson, we are going to look at Celtic artefacts and symbols, continue with our overview of the Book of Invasions, the magick associated with the Cauldron and how to harness elemental magick.