© 2016 Mark Bray ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Heather Marlene Bennett University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Bennett, Heather Marlene, "Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 734. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/734 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Long Live the Revolutions: Fighting for France's Political Future in the Long Wake of the Commune, 1871-1880 Abstract The traumatic legacies of the Paris Commune and its harsh suppression in 1871 had a significant impact on the identities and voter outreach efforts of each of the chief political blocs of the 1870s. The political and cultural developments of this phenomenal decade, which is frequently mislabeled as calm and stable, established the Republic's longevity and set its character. Yet the Commune's legacies have never been comprehensively examined in a way that synthesizes their political and cultural effects. This dissertation offers a compelling perspective of the 1870s through qualitative and quantitative analyses of the influence of these legacies, using sources as diverse as parliamentary debates, visual media, and scribbled sedition on city walls, to explicate the decade's most important political and cultural moments, their origins, and their impact. -

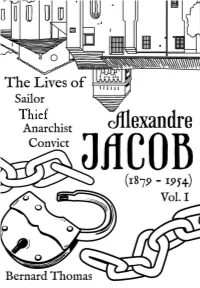

Bernard Thomas Volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M

Thief Jacob Alexandre Marius alias Escande Attila George Bonnot Féran Hard to Kill the Robber Bernard Thomas volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno First Published by Tchou Éditions 1970 This edition translated by Paul Sharkey footnotes translated by Laetitia Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno translated by Jean Weir Published in September 2010 by Elephant Editions and Bandit Press Elephant Editions Ardent Press 2013 introduction i the bandits 1 the agitator 37 introduction The impossibility of a perspective that is fully organized in all its details having been widely recognised, rigor and precision have disappeared from the field of human expectations and the need for order and security have moved into the sphere of desire. There, a last fortress built in fret and fury, it has established a foothold for the final battle. Desire is sacred and inviolable. It is what we hold in our hearts, child of our instincts and father of our dreams. We can count on it, it will never betray us. The newest graves, those that we fill in the edges of the cemeteries in the suburbs, are full of this irrational phenomenology. We listen to first principles that once would have made us laugh, assigning stability and pulsion to what we know, after all, is no more than a vague memory of a passing wellbeing, the fleeting wing of a gesture in the fog, the flapping morning wings that rapidly ceded to the needs of repetitiveness, the obsessive and disrespectful repetitiveness of the bureaucrat lurking within us in some dark corner where we select and codify dreams like any other hack in the dissecting rooms of repression. -

The Spanish Anarchists: the Heroic Years, 1868-1936

The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 the text of this book is printed on 100% recycled paper The Spanish Anarchists THE HEROIC YEARS 1868-1936 s Murray Bookchin HARPER COLOPHON BOOKS Harper & Row, Publishers New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, London memoria de Russell Blackwell -^i amigo y mi compahero Hafold F. Johnson Library Ceirtef' "ampsliire College Anrteret, Massachusetts 01002 A hardcover edition of this book is published by Rree Life Editions, Inc. It is here reprinted by arrangement. THE SPANISH ANARCHISTS. Copyright © 1977 by Murray Bookchin. AH rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission except in the case ofbrief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address ftee Life Editions, Inc., 41 Union Square West, New York, N.Y. 10003. Published simultaneously in Canada by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited, Toronto. First HARPER COLOPHON edition published 1978 ISBN: 0-06-090607-3 78 7980 818210 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 21 Contents OTHER BOOKS BY MURRAY BOOKCHIN Introduction ^ Lebensgefahrliche, Lebensmittel (1955) Prologue: Fanelli's Journey ^2 Our Synthetic Environment (1%2) I. The "Idea" and Spain ^7 Crisis in Our Qties (1965) Post-Scarcity Anarchism (1971) BACKGROUND MIKHAIL BAKUNIN 22 The Limits of the Qty (1973) Pour Une Sodete Ecologique (1976) II. The Topography of Revolution 32 III. The Beginning THE INTERNATIONAL IN SPAIN 42 IN PREPARATION THE CONGRESS OF 1870 51 THE LIBERAL FAILURE 60 T'he Ecology of Freedom Urbanization Without Cities IV. The Early Years 67 PROLETARIAN ANARCHISM 67 REBELLION AND REPRESSION 79 V. -

Fonds Gabriel Deville (Xviie-Xxe Siècles)

Fonds Gabriel Deville (XVIIe-XXe siècles) Répertoire numérique détaillé de la sous-série 51 AP (51AP/1-51AP/9) (auteur inconnu), révisé par Ariane Ducrot et par Stéphane Le Flohic en 1997 - 2008 Archives nationales (France) Pierrefitte-sur-Seine 1955 - 2008 1 https://www.siv.archives-nationales.culture.gouv.fr/siv/IR/FRAN_IR_001830 Cet instrument de recherche a été encodé en 2012 par l'entreprise Numen dans le cadre du chantier de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales sur la base d'une DTD conforme à la DTD EAD (encoded archival description) et créée par le service de dématérialisation des instruments de recherche des Archives Nationales 2 Archives nationales (France) INTRODUCTION Référence 51AP/1-51AP/9 Niveau de description fonds Intitulé Fonds Gabriel Deville Date(s) extrême(s) XVIIe-XXe siècles Nom du producteur • Deville, Gabriel (1854-1940) • Doumergue, Gaston (1863-1937) Importance matérielle et support 9 cartons (51 AP 1-9) ; 1,20 mètre linéaire. Localisation physique Pierrefitte Conditions d'accès Consultation libre, sous réserve du règlement de la salle de lecture des Archives nationales. DESCRIPTION Type de classement 51AP/1-6. Collection d'autographes classée suivant la qualité du signataire : chefs d'État, gouvernants français depuis la Restauration, hommes politiques français et étrangers, écrivains, diplomates, officiers, savants, médecins, artistes, femmes. XVIIIe-XXe siècles. 51AP/7-8. Documents divers sur Puydarieux et le département des Haute-Pyrénées. XVIIe-XXe siècles. 51AP/8 (suite). Documentation sur la Première Guerre mondiale. 1914-1919. 51AP/9. Papiers privés ; notes de travail ; rapports sur les archives de la Marine et les bibliothèques publiques ; écrits et documentation sur les départements français de la Révolution (Mont-Tonnerre, Rhin-et-Moselle, Roer et Sarre) ; manuscrit d'une « Chronologie générale avant notre ère ». -

Anarchism and Religion

Anarchism and Religion Nicolas Walter 1991 For the present purpose, anarchism is defined as the political and social ideology which argues that human groups can and should exist without instituted authority, and especially as the historical anarchist movement of the past two hundred years; and religion is defined as the belief in the existence and significance of supernatural being(s), and especially as the prevailing Judaeo-Christian systemof the past two thousand years. My subject is the question: Is there a necessary connection between the two and, if so, what is it? The possible answers are as follows: there may be no connection, if beliefs about human society and the nature of the universe are quite independent; there may be a connection, if such beliefs are interdependent; and, if there is a connection, it may be either positive, if anarchism and religion reinforce each other, or negative, if anarchism and religion contradict each other. The general assumption is that there is a negative connection logical, because divine andhuman authority reflect each other; and psychological, because the rejection of human and divine authority, of political and religious orthodoxy, reflect each other. Thus the French Encyclopdie Anarchiste (1932) included an article on Atheism by Gustave Brocher: ‘An anarchist, who wants no all-powerful master on earth, no authoritarian government, must necessarily reject the idea of an omnipotent power to whom everything must be subjected; if he is consistent, he must declare himself an atheist.’ And the centenary issue of the British anarchist paper Freedom (October 1986) contained an article by Barbara Smoker (president of the National Secular Society) entitled ‘Anarchism implies Atheism’. -

Anarchist Movements in Tampico & the Huaste

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Peripheries of Power, Centers of Resistance: Anarchist Movements in Tampico & the Huasteca Region, 1910-1945 A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Latin American Studies (History) by Kevan Antonio Aguilar Committee in Charge: Professor Christine Hunefeldt, Co-Chair Professor Michael Monteon, Co-Chair Professor Max Parra Professor Eric Van Young 2014 The Thesis of Kevan Antonio Aguilar is approved and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Co-Chair Co-Chair University of California, San Diego 2014 iii DEDICATION: For my grandfather, Teodoro Aguilar, who taught me to love history and to remember where I came from. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………………………………..…………..…iii Dedication……………………………………………………………………………...…iv Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………….v List of Figures………………………………………………………………………….…vi Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………vii Abstract of the Thesis…………………………………………………………………….xi Introduction……………………………………………………………………………......1 Chapter 1: Geography & Peripheral Anarchism in the Huasteca Region, 1860-1917…………………………………………………………….10 Chapter 2: Anarchist Responses to Post-Revolutionary State Formations, 1918-1930…………………………………………………………….60 Chapter 3: Crisis & the Networks of Revolution: Regional Shifts towards International Solidarity Movements, 1931-1945………………95 Conclusion………………………………………………………………………….......126 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………129 v LIST -

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939

The Anarchist Collectives Workers’ Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939 Sam Dolgoff (editor) 1974 Contents Preface 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introductory Essay by Murray Bookchin 9 Part One: Background 28 Chapter 1: The Spanish Revolution 30 The Two Revolutions by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 30 The Bolshevik Revolution vs The Russian Social Revolution . 35 The Trend Towards Workers’ Self-Management by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 36 Chapter 2: The Libertarian Tradition 41 Introduction ............................................ 41 The Rural Collectivist Tradition by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 41 The Anarchist Influence by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 44 The Political and Economic Organization of Society by Isaac Puente ....................................... 46 Chapter 3: Historical Notes 52 The Prologue to Revolution by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 52 On Anarchist Communism ................................. 55 On Anarcho-Syndicalism .................................. 55 The Counter-Revolution and the Destruction of the Collectives by Sam Dolgoff ....................................... 56 Chapter 4: The Limitations of the Revolution 63 Introduction ............................................ 63 2 The Limitations of the Revolution by Gaston Leval ....................................... 63 Part Two: The Social Revolution 72 Chapter 5: The Economics of Revolution 74 Introduction ........................................... -

Raimundo Lida, Filólogo Y Humanista Peregrino*

Raimundo Lida, filólogo y humanista peregrino* Clara E. Lida y Fernando Lida-García El Colegio de México Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos (INDEC ) n el siglo XIX , sobre todo por la influencia del romanticismo alemán, la filología, junto con la filosofía y la historia, adquirió el prestigio de una ciencia que permitiría conocer los Eorígenes y características culturales de un pueblo o comunidad lingüística y aprehender su espíritu (Volkgeist). Esta disciplina abarcaba una gama tan amplia de temas –desde el estudio de las lenguas y culturas antiguas y modernas, y la historia de sus orígenes, hasta la investiga- ción sobre el folklore y las tradiciones populares–, que el filólogo alemán Georg Curtius (1820- 1885) llegó a afirmar que la filología era a las ciencias humanas lo que la matemática a las ciencias exactas. Esta visión humanística totalizadora se fue circunscribiendo hacia finales del sigloXIX , al reconocer que como disciplina científica se debía sujetar a observaciones y examen sistemáti- cos de los cuales deducir principios y leyes generales. Desde entonces diversos enfoques teó- ricos y epistemológicos desagregaron la filología en disciplinas cada vez más especializadas. España no quedó al margen de este proceso; el desarrollo en ese país de la investigación filo- lógica moderna se debió, sobre todo, a la labor de Ramón Menéndez Pidal (1869-1968), quien sirvió de bisagra entre la tradición romántica alemana, con su búsqueda del Volkgeist en el estudio de los orígenes de la literatura castellana, y las corrientes teóricas y científicas contem- poráneas. Menéndez Pidal –junto con sus colegas y discípulos de la sección de Filología del Centro de Estudios Históricos (CEH ) de Madrid, fundado y dirigido por él en 1910– convirtió al Centro y a su Revista de Filología Española (RFE ), creada en 1914, en dos grandes impulso- res de los estudios filológicos en el mundo hispánico hasta la década de 1930.1 La Argentina recibió esta influencia después de la Primera Guerra Mundial. -

Anarcho-Syndicalism in the 20Th Century

Anarcho-syndicalism in the 20th Century Vadim Damier Monday, September 28th 2009 Contents Translator’s introduction 4 Preface 7 Part 1: Revolutionary Syndicalism 10 Chapter 1: From the First International to Revolutionary Syndicalism 11 Chapter 2: the Rise of the Revolutionary Syndicalist Movement 17 Chapter 3: Revolutionary Syndicalism and Anarchism 24 Chapter 4: Revolutionary Syndicalism during the First World War 37 Part 2: Anarcho-syndicalism 40 Chapter 5: The Revolutionary Years 41 Chapter 6: From Revolutionary Syndicalism to Anarcho-syndicalism 51 Chapter 7: The World Anarcho-Syndicalist Movement in the 1920’s and 1930’s 64 Chapter 8: Ideological-Theoretical Discussions in Anarcho-syndicalism in the 1920’s-1930’s 68 Part 3: The Spanish Revolution 83 Chapter 9: The Uprising of July 19th 1936 84 2 Chapter 10: Libertarian Communism or Anti-Fascist Unity? 87 Chapter 11: Under the Pressure of Circumstances 94 Chapter 12: The CNT Enters the Government 99 Chapter 13: The CNT in Government - Results and Lessons 108 Chapter 14: Notwithstanding “Circumstances” 111 Chapter 15: The Spanish Revolution and World Anarcho-syndicalism 122 Part 4: Decline and Possible Regeneration 125 Chapter 16: Anarcho-Syndicalism during the Second World War 126 Chapter 17: Anarcho-syndicalism After World War II 130 Chapter 18: Anarcho-syndicalism in contemporary Russia 138 Bibliographic Essay 140 Acronyms 150 3 Translator’s introduction 4 In the first decade of the 21st century many labour unions and labour feder- ations worldwide celebrated their 100th anniversaries. This was an occasion for reflecting on the past century of working class history. Mainstream labour orga- nizations typically understand their own histories as never-ending struggles for better working conditions and a higher standard of living for their members –as the wresting of piecemeal concessions from capitalists and the State. -

Neo-Malthusianism, Anarchism and Resistance: World View and the Limits of Acceptance in Barcelona (1904-1914)

■ Article] ENTREMONS. UPF JOURNAL OF WORLD HISTORY Barcelona ﺍ Universitat Pompeu Fabra Número 4 (desembre 2012) www.entremons.org Neo-Malthusianism, Anarchism and Resistance: World View and the Limits of Acceptance in Barcelona (1904-1914) Daniel PARSONS Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona abstract This paper attempts to identify the barriers to the acceptance of Neo-Malthusian discourse among anarchists and sympathizers in the first years of the 20th century in Barcelona. Neo-Malthusian anarchists advocated the use and promotion of contraceptives and birth control as a way to achieve liberation while subscribing to a Malthusian perspective of nature. The revolutionary discourse was disseminated in Barcelona primarily by the journal Salud y Fuerza and its editor Lluis Bulffi from 1904-1914, at the same time sharing ideological goals with traditional anarchism while clashing with the conception of a beneficent and abundant nature which underpinned traditional anarchist thought. Given the cultural, social and political importance of anarchism to the history of Barcelona in particular and Europe in general, further investigation into Neo-Malthusianism and the response to the discourse is needed in order to understand better the generally accepted world-view among anarchists and how they responded to challenges to this vision. This is a topic not fully addressed by current historiography on Neo- Malthusian anarchism. This article is derived from my Master’s thesis in Contemporary History at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona entitled “Neomathusianismo, anarquismo y resistencias: Los límites de su aceptación en Cataluña”, which contains a further exposition of the ideas included herein, as well as a broader perspective on the topic. -

Descarregar (PDF)

BEN panormica coberta tr 17/6/10 10:41 Pgina 1 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Composicin Barcelona, maig 2010 Biblioteca de Catalunya. Dades CIP Izquierdo Ballester, Santiago Panoràmica de l’esquerra nacional, 1868-2006. – 2a ed.. – (Biblioteca de l’Esquerra Nacional) Bibliografia. Índexs ISBN 9788461389957 I. Fundació Josep Irla II. Títol III. Col·lecció: Biblioteca de l’Esquerra Nacional 1. Partits d’esquerra – Catalunya – Història 2. Partits polítics – Catalunya – Història 3. Catalunya – Política i govern 329.17(467.1)”1868/2006” Primera edició abril 2008 Segona edició (revisada i ampliada) maig 2010 Fotografia de coberta: Esparreguera, 6 de desembre de 1931. Visita de Francesc Macià. Josep Maria sagarra / arxiu Històric de la ciutat de Barcelona Dipòsit legal: B-23.320-2010 ISBN: 978-84-613-8995-7 PANORÀMICA DE L’esquerra Nacional 1868-2006 SANTIAGO IZQUIERDO SuMARI Una consideració prèvia ...........................................................................................9 Introducció: la tradició de l’esquerra a Catalunya .............................11 Els precedents ..............................................................................................................25 El Sexenni Revolucionari (1868-1874) ......................................................31 El fracàs de la Primera República ................................................................35 El «catalanisme progressiu» de Josep-Narcís Roca i Ferreras ....................................................39 El liberalisme de Valentí Almirall i els orígens del -

Revolting Peasants: Southern Italy, Ireland, and Cartoons in Comparative Perspective, 1860–1882*

IRSH 60 (2015), pp. 1–35 doi:10.1017/S0020859015000024 r 2015 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Revolting Peasants: Southern Italy, Ireland, and Cartoons in Comparative Perspective, 1860–1882* N IALL W HELEHAN School of History, Classics and Archaeology, University of Edinburgh William Robertson Wing, Old Medical School, Teviot Place, Edinburgh, EH8 9AG, UK E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Peasants in general, and rural rebels in particular, were mercilessly ridiculed in the satirical cartoons that proliferated in European cities from the mid-nineteenth century. There was more to these images than the age-old hostility of the townspeople for the peasant, and this article comparatively explores how cartoons of southern Italian brigands and rural Irish agitators helped shape a liberal version of what was modern by identifying what was not: the revolting peasant who engaged in ‘‘unmanly’’ violence, lacked self-reliance, and was in thrall to Catholic clergymen. During periods of unrest, distinctions between brigands, rebels, and the rural populations as a whole were not always clear in cartoons. Comparison suggests that derogatory images of peasants from southern Italy and Ireland held local peculiarities, but they also drew from transna- tional stereotypes of rural poverty that circulated widely due to the rapidly expanding European publishing industry. While scholarly debates inspired by postcolonial perspectives have previously emphasized processes of othering between the West and East, between the metropole and colony, it is argued here that there is also an internal European context to these relationships based on ingrained class and gendered prejudices, and perceptions of what constituted the centre and the periphery.