Reconsidering the Roman Dictatorship in Livy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ius Militare – Military Courts in the Roman Law (I)

International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR) ISSN 2307-4531 (Print & Online) http://gssrr.org/index.php?journal=JournalOfBasicAndApplied --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Ius Militare – Military Courts in the Roman Law (I) PhD Dimitar Apasieva*, PhD Olga Koshevaliskab a,bGoce Delcev University – Shtip, Shtip 2000, Republic of Macedonia aEmail: [email protected] bEmail: [email protected] Abstract Military courts in ancient Rome belonged to the so-called inconstant coercions (coercitio), they were respectively treated as “special circumstances courts” excluded from the regular Roman judicial system and performed criminal justice implementation, strictly in conditions of war. To repress the war torts, as well as to overcome the soldiers’ resistance, which at moments was violent, the king (rex) himself at first and the highest new established magistrates i.e. consuls (consules) afterwards, have been using various constrained acts. The authority of such enforcement against Roman soldiers sprang from their “military imperium” (imperium militiae). As most important criminal and judicial organs in conditions of war, responsible for maintenance of the military courtesy, were introduced the military commander (dux) and the array and their subsidiary organs were the cavalry commander, military legates, military tribunals, centurions and regents. In this paper, due to limited available space, we will only stick to the main military courts in ancient Rome. Keywords: military camp; tribunal; dux; recruiting; praetor. 1. Introduction “[The Romans...] strictly cared about punishments and awards of those who deserved praise or lecture… The military courtesy was grounded at the fear of laws, and god – for people, weapon, brad and money are the power of war! …It was nothing more than an army, that is well trained during muster; it was no possible for one to be defeated, who knows how to apply it!” [23]. -

A New Perspective on the Early Roman Dictatorship, 501-300 B.C

A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. BY Jeffrey A. Easton Submitted to the graduate degree program in Classics and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s of Arts. Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Committee Members Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date defended: April 26, 2010 The Thesis Committee for Jeffrey A. Easton certifies that this is the approved Version of the following thesis: A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE EARLY ROMAN DICTATORSHIP, 501-300 B.C. Committee: Anthony Corbeill Chairperson Tara Welch Carolyn Nelson Date approved: April 27, 2010 ii Page left intentionally blank. iii ABSTRACT According to sources writing during the late Republic, Roman dictators exercised supreme authority over all other magistrates in the Roman polity for the duration of their term. Modern scholars have followed this traditional paradigm. A close reading of narratives describing early dictatorships and an analysis of ancient epigraphic evidence, however, reveal inconsistencies in the traditional model. The purpose of this thesis is to introduce a new model of the early Roman dictatorship that is based upon a reexamination of the evidence for the nature of dictatorial imperium and the relationship between consuls and dictators in the period 501-300 BC. Originally, dictators functioned as ad hoc magistrates, were equipped with standard consular imperium, and, above all, were intended to supplement consuls. Furthermore, I demonstrate that Sulla’s dictatorship, a new and genuinely absolute form of the office introduced in the 80s BC, inspired subsequent late Republican perceptions of an autocratic dictatorship. -

The Late Republic in 5 Timelines (Teacher Guide and Notes)

1 180 BC: lex Villia Annalis – a law regulating the minimum ages at which a individual could how political office at each stage of the cursus honorum (career path). This was a step to regularising a political career and enforcing limits. 146 BC: The fall of Carthage in North Africa and Corinth in Greece effectively brought an end to Rome’s large overseas campaigns for control of the Mediterranean. This is the point that the historian Sallust sees as the beginning of the decline of the Republic, as Rome had no rivals to compete with and so turn inwards, corrupted by greed. 139 BC: lex Gabinia tabelleria– the first of several laws introduced by tribunes to ensure secret ballots for for voting within the assembliess (this one applied to elections of magistrates). 133 BC – the tribunate of Tiberius Gracchus, who along with his younger brother, is seen as either a social reformer or a demagogue. He introduced an agrarian land that aimed to distribute Roman public land to the poorer elements within Roman society (although this act quite likely increased tensions between the Italian allies and Rome, because it was land on which the Italians lived that was be redistributed). He was killed in 132 BC by a band of senators led by the pontifex maximus (chief priest), because they saw have as a political threat, who was allegedly aiming at kingship. 2 123-121 BC – the younger brother of Tiberius Gracchus, Gaius Gracchus was tribune in 123 and 122 BC, passing a number of laws, which apparent to have aimed to address a number of socio-economic issues and inequalities. -

Liberation and Liberality in Roman Funerary Commemoration

This is a repository copy of "The mourning was very good". Liberation and liberality in Roman funerary commemoration. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/138677/ Version: Published Version Book Section: Carroll, P.M. (2011) "The mourning was very good". Liberation and liberality in Roman funerary commemoration. In: Hope, V.M. and Huskinson, J., (eds.) Memory and Mourning: Studies on Roman Death. Oxbow Books Limited , pp. 125-148. ISBN 9781842179901 © 2011 Oxbow Books. Reproduced in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 8 ‘h e mourning was very good’. Liberation and Liberality in Roman Funerary Commemoration Maureen Carroll h e death of a slave-owner was an event which could bring about the most important change in status in the life of a slave. If the last will and testament of the master contained the names of any fortunate slaves to be released from servitude, these individuals went from being objects to subjects of rights. -

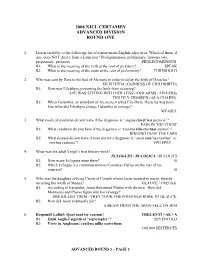

2008 Njcl Certamen Advanced Division Round One

2008 NJCL CERTAMEN ADVANCED DIVISION ROUND ONE 1. Listen carefully to the following list of synonymous English adjectives. Which of them, if any, does NOT derive from a Latin root? Prolegomenous, preliminary, introductory, preparatory, prefatory PROLEGOMENOUS B1: What is the meaning of the verb at the root of prefatory? SPEAK B2: What is the meaning of the noun at the root of preliminary? THRESHOLD 2. Who was sent by Hera to the bed of Alcmene in order to delay the birth of Heracles? EILEITHYIA (GODDESS OF CHILDBIRTH) B1: How was Eileithyia preventing the birth from occuring? SHE WAS SITTING WITH HER LEGS (AND ARMS / FINGERS) TIGHTLY CROSSED (AS A CHARM). B2: When Galanthis, an attendant of Alcmene, tricked Eileithyia, Heracles was born. Into what did Eileithyia change Galanthis in revenge? WEASEL 3. What medical condition do you have if the diagnosis is “angina (ăn-jī΄nƏ) pectoris”? PAIN IN THE CHEST B1: What condition do you have if the diagnosis is “tinnitus (tĭn-eye-tus) aurium”? RINGING IN/OF THE EARS B2: What disease do you have if your doctor’s diagnosis is “sacer (săs΄Ər) morbus” or “morbus caducus”? EPILEPSY 4. What was the adult Vergil’s first literary work? ECLOGUES / BUCOLICA / BUCOLICS B1: How many Eclogues were there? 10 B2: Which Eclogue is a commiseration to Cornelius Gallus on the loss of his mistress? 10 5. Who was the daughter of King Creon of Corinth whom Jason wanted to marry, thereby incurring the wrath of Medea? GLAUCE / CREUSA B1: According to Euripides, Jason threatened Medea with divorce. How did Mermerus and Pheres figure into her revenge? SHE KILLED THEM / THEY TOOK THE POISONED ROBE TO GLAUCE. -

Are a Thousand Words Worth a Picture?: an Examination of Text-Based Monuments in the Age

Are a Thousand Words Worth a Picture?: An Examination of Text-Based Monuments in the Age of Augustus Augustus is well known for his exquisite mastery of propaganda, using monuments such as the Ara Pacis, the summi viri, and his eponymous Forum to highlight themes of triumph, humility, and the monumentalization of Rome. Nevertheless, Augustus’ use of the written word is often overlooked within his great program, especially the use of text-based monuments to enhance his message. The Fasti Consulares, the Fasti Triumphales, the Fasti Praenestini, and the Res Gestae were all used to supplement his better-known, visual iconography. A close comparison of this group of text-based monuments to the Ara Pacis, the Temple of Mars Ultor, and the summi viri illuminates the persistence of Augustus' message across both types of media. This paper will show how Augustus used text-based monuments to control time, connect himself to great Roman leaders of the past, selectively redact Rome’s recent history, and remind his subjects of his piety and divine heritage. The Fasti Consulares and the Fasti Triumphales, collectively referred to as the Fasti Capitolini have been the subject of frequent debate among Roman archaeologists, such as L.R. Taylor (1950), A. Degrassi (1954), F. Coarelli (1985), and T.P. Wiseman (1990). Their interest has been largely in where the Fasti Capitolini were displayed after Augustus commissioned the lists’ creation, rather than how the lists served Augustus’ larger purposes. Many scholars also study the Fasti Praenestini; yet, it is usually in the context of Roman calendars generally, and Ovid’s Fasti specifically (G. -

75 AD NUMA POMPILIUS Legendary, 8Th-7Th Century B.C. Plutarch Translated by John Dryden

75 AD NUMA POMPILIUS Legendary, 8th-7th Century B.C. Plutarch translated by John Dryden Plutarch (46-120) - Greek biographer, historian, and philosopher, sometimes known as the encyclopaedist of antiquity. He is most renowned for his series of character studies, arranged mostly in pairs, known as “Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans” or “Parallel Lives.” Numa Pompilius (75 AD) - A study of the life of Numa Pompilius, an early Roman king. NUMA POMPILIUS THOUGH the pedigrees of noble families of Rome go back in exact form as far as Numa Pompilius, yet there is great diversity amongst historians concerning the time in which he reigned; a certain writer called Clodius, in a book of his entitled Strictures on Chronology, avers that the ancient registers of Rome were lost when the city was sacked by the Gauls, and that those which are now extant were counterfeited, to flatter and serve the humour of some men who wished to have themselves derived from some ancient and noble lineage, though in reality with no claim to it. And though it be commonly reported that Numa was a scholar and a familiar acquaintance of Pythagoras, yet it is again contradicted by others, who affirm that he was acquainted with neither the Greek language nor learning, and that he was a person of that natural talent and ability as of himself to attain to virtue, or else that he found some barbarian instructor superior to Pythagoras. Some affirm, also, that Pythagoras was not contemporary with Numa, but lived at least five generations after him; and that some other Pythagoras, a native of Sparta, who, in the sixteenth Olympiad, in the third year of which Numa became king, won a prize at the Olympic race, might, in his travel through Italy, have gained acquaintance with Numa, and assisted him in the constitution of his kingdom; whence it comes that many Laconian laws and customs appear amongst the Roman institutions. -

Histoire Romaine

HISTOIRE ROMAINE EUGÈNE TALBOT PARIS - 1875 AVANT-PROPOS PREMIÈRE PARTIE. — ROYAUTÉ CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. SECONDE PARTIE. — RÉPUBLIQUE CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. - CHAPITRE IV. - CHAPITRE V. - CHAPITRE VI. - CHAPITRE VII. - CHAPITRE VIII. - CHAPITRE IX. - CHAPITRE X. - CHAPITRE XI. - CHAPITRE XII. - CHAPITRE XIII. - CHAPITRE XIV. - CHAPITRE XV. - CHAPITRE XVI. - CHAPITRE XVII. - CHAPITRE XVIII. - CHAPITRE XIX. - CHAPITRE XX. - CHAPITRE XXI. - CHAPITRE XXII. TROISIÈME PARTIE. — EMPIRE CHAPITRE PREMIER. - CHAPITRE II. - CHAPITRE III. AVANT-PROPOS. LES découvertes récentes de l’ethnographie, de la philologie et de l’épigraphie, la multiplicité des explorations dans les diverses contrées du monde connu des anciens, la facilité des rapprochements entre les mœurs antiques et les habitudes actuelles des peuples qui ont joué un rôle dans le draine du passé, ont singulièrement modifié la physionomie de l’histoire. Aussi une révolution, analogue à celle que les recherches et les œuvres d’Augustin Thierry ont accomplie pour l’histoire de France, a-t-elle fait considérer sous un jour nouveau l’histoire de Rome et des peuples soumis à son empire. L’officiel et le convenu font place au réel, au vrai. Vico, Beaufort, Niebuhr, Savigny, Mommsen ont inauguré ou pratiqué un système que Michelet, Duruy, Quinet, Daubas, J.-J. Ampère et les historiens actuels de Rome ont rendu classique et populaire. Nous ne voulons pas dire qu’il ne faut pas recourir aux sources. On ne connaît l’histoire romaine que lorsqu’on a lu et étudié Salluste, César, Cicéron, Tite-Live, Florus, Justin, Velleius, Suétone, Tacite, Valère Maxime, Cornelius Nepos, Polybe, Plutarque, Denys d’Halicarnasse, Dion Cassius, Appien, Aurelius Victor, Eutrope, Hérodien, Ammien Marcellin, Julien ; et alors, quand on aborde, parmi les modernes, outre ceux que nous avons nommés, Machiavel, Bossuet, Saint- Évremond, Montesquieu, Herder, on comprend l’idée, que les Romains ont développée dans l’évolution que l’humanité a faite, en subissant leur influence et leur domination. -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Expulsion from the Senate of the Roman Republic, C.319–50 BC

Ex senatu eiecti sunt: Expulsion from the Senate of the Roman Republic, c.319–50 BC Lee Christopher MOORE University College London (UCL) PhD, 2013 1 Declaration I, Lee Christopher MOORE, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Thesis abstract One of the major duties performed by the censors of the Roman Republic was that of the lectio senatus, the enrolment of the Senate. As part of this process they were able to expel from that body anyone whom they deemed unequal to the honour of continued membership. Those expelled were termed ‘praeteriti’. While various aspects of this important and at-times controversial process have attracted scholarly attention, a detailed survey has never been attempted. The work is divided into two major parts. Part I comprises four chapters relating to various aspects of the lectio. Chapter 1 sees a close analysis of the term ‘praeteritus’, shedding fresh light on senatorial demographics and turnover – primarily a demonstration of the correctness of the (minority) view that as early as the third century the quaestorship conveyed automatic membership of the Senate to those who held it. It was not a Sullan innovation. In Ch.2 we calculate that during the period under investigation, c.350 members were expelled. When factoring for life expectancy, this translates to a significant mean lifetime risk of expulsion: c.10%. Also, that mean risk was front-loaded, with praetorians and consulars significantly less likely to be expelled than subpraetorian members. -

Augustus' Memory Program

Augustus’ memory program: Augustus as director of history Freek Mommers, F.A.J. S4228421 Summary: Chapter 1: Introduction 2 Chapter 2: Augustus’ troubling past 7 Chapter 3: Commemoration through ceremonies and festivals 11 Chapter 4: Commemoration through literature and inscriptions 20 Chapter 5: Commemoration through monuments 29 Chapter 6: Conclusion 35 Bibliography 36 1 Introduction Augustus is one of the most studied Roman emperors in modern literature but a lot of the period is still unknown or debated.1 The image of Augustus is usually dominated by his most successful years as princeps of Rome.2 Augustus represented himself as an example and as a protector of order, morals and peace.3 The civil war between Augustus and Anthony however was a period filled with chaos and terror. In times of war it was close to impossible to proceed in a moral and peaceful way. Augustus’ claims as an example of order and good morals would obviously be damaged by his troubling past. Therefore the memory of the civil war against Anthony culminating in the battle of Actium in 31 B.C. needed some conscious adaptations for Augustus’ later representation. The now well known history and literature of the civil war are mostly written in an Augustan perspective, a history of the winner. This thesis will try to answer the following question: How did Augustus adapt the memory of his troubling past of his civil war against Anthony in his commemoration practices? The civil war and the decisive battle of Actium play important but controversial roles in Augustan commemoration. Details of the civil war often were deliberately camouflaged or concealed in Augustan sources. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Livy the Historian Livy , or in full Titus Livius, was born at Patavium in northern Italy (Padua today) in 59 bc, and so lived through the turbulent years of the fall of the Roman Republic into the calm and politically controlled era of one-man rule under Augustus and his successor Tiberius. 1 According to St Jerome’s Chronicle he died in ad 17. He seems not to have held public offi ce or done any military service. Apart from some essays, now lost, on philosophy and rhetoric, he undertook in his late twenties to compose an up-to-date history of Rome drawing on mostly Roman but also some Greek predecessors. He entitled it From the Foundation of the City ( Ab Urbe Condita ): to all Romans their City was unique. The history eventually amounted to 142 books, taking Rome’s history from its traditional foundation-date of 753 bc down to the year 9 bc — a colossal achievement, much lengthier than Gibbon’s Decline and Fall , for instance. Of it only the fi rst ten Books and then Books 21–45 survive. Books 6–10 take the story of Rome from 390 bc down to the year 293. Evidence in the work indicates that Livy began writing in the early 20s bc, for around 18 bc he reached Book 28. A subheading to a surviving résumé (epitome) of the lost book 121 states that it was published after Augustus’ death in ad 14: some- thing that probably held true, too, for those that followed. The his- tory ended at the year 9 bc.