Faculty Experiences in Delivering an American University Curriculum in an International Branch Campus 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Download the Postgraduate Fair 2017

48 Course Sum- executive education guide POSTGRADUATE FAIR 2017 MBA AND MASTERS 9 SEP 2017, SAT Raffles City Convention Centre 47 INSTITUTIONS 36 INFO SESSIONS FREE ADMISSION What is the Postgraduate Fair? Event Format The Postgraduate Fair 2017 helps Professionals, u 36 Info Sessions (Masters & MBA) Managers and Executives explore postgraduate u 47 Education Institutions with over 80 courses courses that can help bring their careers to the next level. Explore MBA and Masters courses that are offered by local and Event Information international institutions. Speak with 47 Venue: Raffles City Convention Centre - Collyer Ballroom leading institutions and choose from Date: 9 Sep 2017 (Sat) / Time : 11:00am to 5:00pm 36 information sessions to gain insights Entry: Free Admission (Registration is required for entry) into the different programmes available. Register at www.Postgrad.com.sg Print Specifications – Full Colour Corporate Identity 29 08 08 IAL Participating Institutions Corporate Identity Management Development Instute of Singapore In Partnership GMATZ NE Technical University of Munich Asia ORGANISED BY Register now at www.Postgrad.com.sg 42HEADHUNT POSTGRADUATE FAIR 2017 \ MBA AND MASTERS executive HEADHUNT POSTGRADUATE FAIR 2017 \ MBA AND MASTERS education guide AVENTIS SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT CPE Reg. No. – 200700458M | Reg. Period - 20/05/2014 to 19/05/2018 JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY CPE Registration No. 200100786K | Period of Registration- 13 July 2014 to 12 July 2018 University of Roehampton London Postgraduate Programmes (3:20pm – 3:40pm): Postgraduate Programmes (2:20pm – 2:40pm): • MBA • Graduate Certificate of Career Development • MSc International Management with Marketing • Graduate Diploma of Psychology • MSc International Management with HR Management • Masters of Guidance and Counselling • MA Integrative Counselling & Psychotherapy • Master of Psychology (Clinical) CUHK BUSINESS SCHOOL Postgraduate Programmes (4:00pm – 4:20pm): KAPLAN HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTE • MBA CPE Reg. -

SCHOOL PROFILE 2019 INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL CEEB Code: 687006 UCAS School ID: 45765 | IB School Code: 003400

ST. JOSEPH’S INSTITUTION SCHOOL PROFILE 2019 INTERNATIONAL SCHOOL CEEB Code: 687006 UCAS School ID: 45765 | IB School Code: 003400 MISSION STATEMENT: Enabling students, within a Lasallian community, to learn how to learn and learn how to live, empowering them to become people of integrity and people for others. SJI International was founded in January 2007 and is part of the 339-year Catholic educational tradition of the De La Salle Christian Brothers. We graduated our first class of 58 students in November 2009 and are one of three schools in Singapore with a license to educate both Singaporean and international students. The learning experience is central to everything we do, as we reflect an international, modern-day Lasallian education. Learning at the High School has four core pillars, each providing experiential opportunities for a truly holistic education leading to the highest level of personal growth: Academic Learning, Service Learning, Co-Curricular Learning and Outdoor Education. ACADEMIC LEARNING The language of instruction is English. Grade 11 and 12 (IB Diploma) All students follow the International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma programme which requires students to study six subjects, three at the Higher Level and three at the Standard Level, as well as a Theory of Knowledge course. Students also complete a 4000 word Extended Essay and fulfil requirements in Creativity, Activity and Service. The maximum score on the IB Diploma is 45 points, with 42 points from the six subjects and 3 points from the Extended Essay and Theory of Knowledge. Grade 9 and 10 (IGCSE Curriculum) All students follow the Cambridge International General Certificate of Secondary Education (IGCSE) curriculum and normally sit eight IGCSEs; students who also take Additional Mathematics sit nine. -

Class Licensed Institutions & Schools

RESPECTING COPYRIGHT! CLASS LICENSED INSTITUTIONS & SCHOOLS GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS & GOVERNMENT-LINKED EDUCATION INSTITUTES: All Ministry of Education (MOE) primary schools, secondary schools, junior colleges; Most Government-aided primary schools, secondary schools and junior colleges; All Independent Schools; All Specialised Independent Schools; All Specialised Schools. It also includes the following: • All polytechnics - Nanyang Poly, Ngee Ann Poly, Republic Poly, Singapore Poly and Temasek Poly • All universities - National University of Singapore (NUS); Nanyang Technological University (NTU); National Institute of Education (NIE); Singapore Management University (SMU); Singapore Institute of Technology (SIT); Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD); Singapore University of Social Science (SUSS) • Building and Construction Authority Academy (BCA) • Institute of Adult Learning (IAL) • Institute of Technical Education (ITE) • MUIS Academy • SEAMEO Regional Language Centre • Singapore Institute of Management (SIM) • Social Service Institute NON-GOVERNMENT INSTITUTIONS: • Academia English and Writing Centre • Academies Australasia College • Allied Educators College • Anglo-Chinese School (International) • Ascensia International School • Australian International School Singapore • British Council • Curtin Singapore • EtonHouse International Education Group • Electronics Industries Training Centre • Hwa Chong International School Page 1 of 2 • INSEAD • James Cook University • Kaplan Higher Education Institute • Kaplan Higher -

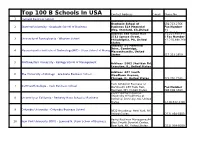

Top 100 B Schools In

Top 100 B Schools In USA Contact Address E-mail Phone No 1 Harvard Business School Address: Stanford +1 Graduate School of 650.723.2766 2 Stanford University - Graduate School of Business Business 518 Memorial Fax Number Way, Stanford, CA,United +1 AddressStates 344 Vance Hall +1.215.898.847650.725.7831 3733 Spruce Street, 8 Fax Number 3 University of Pennsylvania - Wharton School Philadelphia, PA, United +1.215.898.269 States 5 Address :50 Memorial Drive, Cambridge, 4 Massachusetts Institute of Technology(MIT) - Sloan School of ManagementMassachusetts, United States 617-253-2659 5 Northwestern University - Kellogg School of Management Address :2001 Sheridan Rd, Evanston, IL, United States Address :807 South 6 The University of Chicago - Graduate Business School Woodlawn Avenue, Chicago, IL, United States 773.702.7743. Tuck School of Business at 7 Dartmouth College - Tuck Business School Dartmouth 100 Tuck Hall, Fax Number Hanover, NH, United States 603-646-1308 2220 Piedmont Avenue University of California at 8 University of California - Berkeley Haas School of Business Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States 1-510-642-1405 9 Columbia University - Columbia Business School 3022 Broadway, New York, NY, United States (212) 854-5553 Henry Kaufman Manageme,44 10 New York University (NYU) - Leonard N. Stern School of Business West Fourth Streetnt Center, New York, NY, United States (212) 998-0100 UCLA Anderson School of 201-825-6944 11 University of California Los Angeles - John E. Anderson School of ManagementManagement Box 951481, Los Fax Number AngelesStephen ,M. CA, Ross United School States of 201-825-8582 Business University of Michigan 701 Tappan 12 The University of Michigan - Stephen M. -

Online MBA Programmes Emerge As Pandemic Prompts Temporary Closures Some of the Top MBA Providers Are Planning to Launch Online Programmes in the Future

RANKINGS: MBA PROGRAMMES AND PROVIDERS S P Jain main branch Online MBA programmes emerge as pandemic prompts temporary closures Some of the top MBA providers are planning to launch online programmes in the future. n this year’s Singapore Business Aventis School of Management As executives Management. Review rankings of the largest academic director Stanley Soh become Aventis is also currently in talks IMBA programmes, INSEAD told Singapore Business Review that strapped for about launching an online MBA MBA emerged on top, with a they received a spike in requests time, balancing programme, after digitising some of whopping 1,008 students enrolled in from prospective students who are their careers their Graduate Diploma programme. the programme. It is followed by S P considering taking an online MBA, and personal Further, Kaplan Higher Education Jain Master of Global Business with especially in light of the COVID-19 commitments, is considering the possibility of 239 students, and Manchester Global pandemic and the increasing online MBA launching online MBA programmes. Master of Business Administration by digitisation of business school programmes Currently, they are offering an online Alliance Manchester Business School offerings. will see a surge Master’s programme for Executive with 219. In response to such demand, in popularity. Master in Leadership and Strategy Amongst MBA providers, INSEAD MBA providers have increasingly and Innovation, in partnership with with just its sole MBA programme been bringing such programmes Murdoch University. still has the most number of MBA in Singapore. For instance, a “We believe an online MBA students, followed by S P Jain School spokesperson from the Management programme will help our students as of Global Management and the Development Institute of Singapore it offers greater flexibility in terms of National University of Singapore (MDIS) shared that they are offering managing their time and not being (NUS) Business School with 509 and five online or e-learning MBA confined to a classroom setting. -

Specialised Master Programmes Feature PG 21

HeadHunt Supplement - September 2019 Specialised Master Programmes Feature PG 21 UNIVERSITY COURSE SUMMARY Postgraduate Scholarship – Snapshot PG 44 - 54 PG 10-11 POSTGRADUATE FAIR 2O19 MBA, MASTERS, PhD & CE RAFFLES CITY CONVENTION CENTRE | 7 SEPT 2019, SAT 58 INSTITUTIONS 42 INFO SESSIONS FREE ADMISSION MICA (P) 022/06/2019 executive 2 Singapore Institute of Technology education guide executive education guide NUS Business School 3 executive 4 Singapore University of Technology and Design education guide EMPOWERING OUR STUDENTS TO BE FUTURE INNOVATORS, DESIGNERS AND LEADERS. CHOOSE SUTD MULTIDISCIPLINARY GRADUATE PROGRAMMES TODAY. PROGRAMMES ENQUIRIES - Master of Innovation by Design (New!) [email protected] - Master of Engineering (Research) https://sutd.edu.sg/Admissions/Graduate - Master of Science in Security by Design - Master of Science in Urban Science, Policy and Planning - SUTD-CGU Dual Masters in Nano- Electronic Engineering and Design - Engineering Doctorate - PhD Programme - SUTD-NUS Joint PhD Programme A BETTER WORLD BY DESIGN. executiLKCSB_EEGve Headstart_FPFC_200wx280h_Aug.pdf 1 2/7/19 10:02 AM education guide Singapore Management University 5 THE NEW ECONOMY NEEDS A NEW WAY OF THINKING. MASTERS LEE KONG CHIAN SCHOOL OF BUSINESS POSTGRADUATE PROGRAMMES EXECUTIVE MASTER OF MASTER OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN 22ND 43RD BUSINESS GLOBALLY1 BUSINESS GLOBALLY4 MANAGEMENT ADMINISTRATION ADMINISTRATION • Benefit from the collective experience of the • Gain industry experience working with real • Benefit from a Global-Asian Management most senior EMBA class profile in the world clients and budgets via the new Overseas Curriculum that covers the latest trends • Curriculum co-designed by 100 Immersion Programme (OIP) in business management senior executives and business • Enjoy lifelong ROI – • Flexible learning options to suit your needs. -

The Jobscentral Learning Rankings and Survey Series Is the Largest and Most Comprehensive Research on Singapore’S Private Education Landscape

JobsCentral is a CareerBuilder Company. TThehe JJobsCentralobsCentral LLearningearning Rankings and Survey Report 2012 December 2012 A study of the private higher education rankings and learning preferences in Singapore This report is published by: JobsCentral Pte Ltd www.jobscentral.com.sg 3A International Business Park, #08-08, ICON@IBP, Tower A, Singapore 609935 Survey Contacts: Alythea Ho [email protected] | Jonathan Tay [email protected] Copyright © 2012 JobsCentral Pte Ltd This document is copyrighted; any unauthorized use of it may violate copyright, trademark and other laws. For permission to use content from this document or reprints, please contact JobsCentral at [email protected] or call (65) 6778 5288 2012 JobsCentral Learning Rankings and Survey 01 IIntroductionntroduction Since its launch in 2009, the JobsCentral Learning Rankings and Survey series is the largest and most comprehensive research on Singapore’s private education landscape. The report is based on an independent research project commissioned by the JobsCentral Group, and comprises two main categories: rankings of Singapore’s private education institutes, and learning preferences findings of the general population aged 15 and above. 5,476 respondents’ data was collected via a voluntary online questionnaire from September to October this year. Incomplete and duplicated responses were discarded and do not contribute to this count. This report includes findings which may be of interest to employers seeking to understand what motivates employees to pursue further education, and the expected salary increments after obtaining higher qualifications. Prospective adult students may also find the rankings useful in making informed decisions for a school and course of study. -

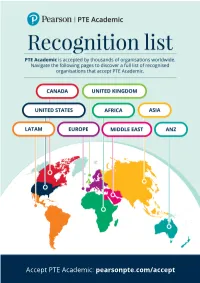

Global Recognition List August

Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept Africa Egypt • Global Academic Foundation - Hosting university of Hertfordshire • Misr University for Science & Technology Libya • International School Benghazi Nigeria • Stratford Academy Somalia • Admas University South Africa • University of Cape Town Uganda • College of Business & Development Studies Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept August 2021 Africa Technology & Technology • Abbey College Australia • Australian College of Sport & Australia • Abbott School of Business Fitness • Ability Education - Sydney • Australian College of Technology Australian Capital • Academies Australasia • Australian Department of • Academy of English Immigration and Border Protection Territory • Academy of Information • Australian Ideal College (AIC) • Australasian Osteopathic Technology • Australian Institute of Commerce Accreditation Council (AOAC) • Academy of Social Sciences and Language • Australian Capital Group (Capital • ACN - Australian Campus Network • Australian Institute of Music College) • Administrative Appeals Tribunal • Australian International College of • Australian National University • Advance English English (AICE) (ANU) • Alphacrucis College • Australian International High • Australian Nursing and Midwifery • Apex Institute of Education School Accreditation Council (ANMAC) • APM College of Business and • Australian Pacific College • Canberra Institute of Technology Communication • Australian Pilot Training Alliance • Canberra. Create your future - ACT • ARC - Accountants Resource -

27 Feb 2021, Sat

HeadHunt Supplement - February 2021 UNIVERSITY COURSE SUMMARY PG 22 - 29 LEVEL UP YOUR FUTURE NOW | 27 FEB 2021, SAT 18 INSTITUTIONS VIP 1 TO 1 CHATS FREE VIRTUAL FAIR MCI (P) 068/06/2020 executive 2 Infocomm Media Development Authority education guide executive education guide Singapore Management University 3 A New Generation of Leaders for the Changing World. MASTERS New knowledge, new skills, new ideas — the demands of a new normal also bring new opportunities for a new generation of leaders. Tailored for an increasingly complex world, the suite of postgraduate professional programmes offered by Singapore Management University will equip you with the knowledge and skills required to meet the dynamic needs of industry and society. Experience the innovative curriculum and pedagogy that we are known for, and emerge as a polished leader, agile and resilient for a contemporary economy. Master Your Future today. From left to right: Mary Grace Joy (Philippines), Master of IT in Business, Class of 2017 Shim Euhkyung (Korea), Juris Doctor Programme, Class of 2017 Jeremy Gray Stobie (USA), Master of Professional Accounting, Class of 2018 Vena Yunitantria (Indonesia), Master of Science in Management, Class of 2017 THE SMU MASTERS NETWORKING AND CAREER ADVANTAGE GLOBAL RECOGNITION INTERACTIVE PEDAGOGY INNOVATIVE CURRICULUM OPPORTUNITIES CITY CAMPUS OUR POSTGRADUATE PROFESSIONAL PROGRAMMES LEE KONG CHIAN SCHOOL OF BUSINESS SCHOOL OF ACCOUNTANCY Executive Master of Business Administration (EMBA) Master of Professional Accounting (MPA) SMU MASTERS Master of Business Administration (MBA) MSc in Accounting (MSA) DAY 2021 ONLINE MSc in Management (MiM) MSc in CFO Leadership (MCFO)* Sat, 27 Mar, 12pm - 5pm MSc in Wealth Management (MWM) www.smu.edu.sg/mastersday SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS MSc in Applied Finance (MAF) MSc in Economics (MSE) MSc in Quantitative Finance (MQF) Accelerate your career through MSc in Financial Economics (MSFE) Global Master of Finance Dual-Degree (GMF)* our Masters programmes. -

Aventis School of Management Amity Global

AMITY GLOBAL INSTITUTE CPE Reg. No. – 200606974C | Reg. Period – 18/07/2019 to 17/07/2023 JAMES COOK UNIVERSITY University of London CPE Reg. No. – 200100786K | Reg. Period – 13/07/2018 to 12/07/2022 • Master of Business Administration (with 5 Specialism) • Doctor of Philosophy University of Northampton • Master of Philosophy • Master of Business Administration • Master of Guidance and Counselling University of Stirling • Master of Planning and Urban Design (Majoring in Disaster Resilience and • Master of Science Big Data Sustainable Tropical Urbanism) • Master of Science Financial Technology (FinTech) AVENTIS SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT CPE Reg. No. – 200700458M | Reg. Period - 20/05/2019 to 19/05/2021 KAPLAN HIGHER EDUCATION INSTITUTE California State University CPE Reg. No. – 198600044N | Reg. Period – 17/08/2018 to 16/08/2022 • MBA (Int’l Management/ IT Management/ Finance) Kaplan Postgraduate Programmes Roehampton University London • Master of Health Services Management – Griffith University • Masters of Business Administration (MBA) • Master of Counselling – Monash University • Masters in Global Marketing • Double Master (MBA – MHRM) – Murdoch University • Masters in Global Human Resources Management • Master of Business Administration – Northumbria University • Masters in Integrative Counselling & Psychotherapy • Master of Science in Finance – University College Dublin University of West London • Master of Science in Logistics and Supply Chain Management • Master of Cyber Security – University College Dublin • Master of Applied Project Management • Master of Engineering (Engineering Management) – University of South Australia University of East London • Master of Professional Accounting KAPLAN HIGHER EDUCATION ACADEMY CPE Reg. No. – 199701260K | Reg. Period – 20/05/2018-19/05/2022 • Preparatory Course for the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) Examination • Preparatory Course for Chartered Financial Analyst® (CFA®) Examination EAST ASIA INSTITUTE OF MANAGEMENT • Preparatory Course for CPA Program CPE Reg. -

List AWS Educate Institutions

Educate Institution City Country 1337 KHOURIBGA Morocco 1daoyun 无锡 China 3aaa Apprenticeships Derby United Kingdom 3W Academy Paris France 42 São Paulo sao paulo Brazil 42 seoul seoul Korea, Republic of 42 Tokyo Minato-ku Tokyo Japan 42Quebec QUEBEC Canada A P Shah Institute of Technology Thane West India A. D. Patel Institute of Technology Ahmedabad India A.V.C. College of Engineering Mayiladuthurai India Aalim Muhammed Salegh College of Engineering Avadi-IAF India Aaniiih Nakoda College Harlem United States AARHUS TECH Aarhus N Denmark Aarhus University Aarhus Denmark Aarupadai Veedu Institute of Technology Kanchipuram(Dt) India Abb Industrigymansium Västerås Sweden Abertay University Dundee United Kingdom ABES Engineering College Ghaziabad India Abilene Christian University Abilene United States Research Pune Pune India Abo Akademi University Turku Finland Academia de Bellas Artes Semillas Ltda Bogota Colombia Academia Desafio Latam Santiago Chile Academia Sinica Taipei Taiwan Academie Informatique Quebec-Canada Lévis Canada Academy College Bloomington United States Academy for Career Exploration PROVIDENCE United States Academy for Urban Scholars Columbus United States ACAMICA Palermo Argentina Accademia di Belle Arti di Cuneo Cuneo Italy Achariya College of Engineering Technology Puducherry India Acharya Institute of Technology Bangalore India Acharya Narendra Dev College New Delhi India Achievement House Cyber Charter School Exton United States Acropolis Institute of Technology & Research, Indore Indore India ACT AMERICAN COLLEGE -

University Ibpolicies2015allcountries.Pdf

COUNTRY_NAME UNIVERSITY_NAME POLICY ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA University of Health Sciences Antigua The University of Health Sciences Antigua School of Medicine recognizes ARGENTINA Escuela Superior Técnica del Ejército Elthe Instituto IB program Superior and accordsdel Ejército special permitirá consideration el ingreso for directo students a las presenting carreras ARGENTINA ArgentinoESEADE - Instituto Universitario Poliacuteticade grado que dese reconocimientocursan en la Escuela acadeacutemico Superior Técnica por ESEADE a los graduados 1. ARGENTINA Instituto Tecnológico de Buenos Aires ReconocimientoESEADE, de equivalencias para el ingreso al primer año en la ARGENTINA Instituto(ITBA) Universitario CEMIC ElEscuela Instituto de Universitario Ingeniería. CEMIC permite el ingreso directo en las carreras ARGENTINA International Buenos Aires Hotel & deIBAHRS grado ofreceque en a ella los seestudiantes cursan a aquelloscon Diploma alumnos del Bachillerato que hayan obtenido el ARGENTINA LincolnRestaurant University School College (IBAHRS LaInternacional Lincoln University el libre yCollege directo ofreceingreso crédito a sus universitariociclos lectivos de de hasta International un año ARGENTINA Ott College Elpara Ott el College título o otorgamaterias la eximiciónaprobadas del del examen BI. La Universidadde inglés del ofrece ingreso los a las ARGENTINA Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina carrerasLa Universidad terciarias Católica de Ott Argentina College y establece la posibilidad a partir de promocionardel ingreso al la curso ARGENTINA