Cwaas Transactions 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Village News Summer Edition

Curry Night Buffet (£15.00 per person, at the Lacy Thompson Hall) Saturday 6 July 2019 at 7.30pm ------------------ooo-------------------- A variety of curry dishes & accompaniments Such as rice, poppadoms, chutneys & pickles, incl one drink (additional drinks will be available to buy) A choice of desserts Tea & Coffee (a bar will sell wine, beer and soft drinks) ------------------------------ooo--------------------------------- Curry Evening – Lacy Thompson Hall – 6 July 2019 – 7.30pm Name ………………………………………………………………………. Phone No ………………………… Email ………………………………. Full Address ………………………………………………………………………………………………… The Village News ……………………………………………………………………………………… No of Tickets required ……. (….. of which are Vegetarian) Summer Edition ------------------------------------------------------------------------- Please complete this form and return it (together with your cheque made out to ‘Lacy Thompson Memorial Hall’) June - August 2019 By Friday 21 June at the latest* to: Tim Arndt, 1 Tindale Terrace, Tindale Fell, CA8 2QJ. Thank you. Covering Farlam, Milton, Kirkhouse, (* due to restricted space, only 25 tickets are available) ForestHead, Hallbankgate, Coal Fell, Tindale and Midgeholme Hello and welcome to the Summer edition of The Village News. Farlam 100+ Club I’m sure we can all still remember the remarkable summer months enjoyed last year: the balmy evenings, burnt lawns and sun tan bottles reached for! 2019-2020 Would it be too much to ask for a repeat this year? This third edition of the Village News covers the period of June to August, and we’d like to thank all those who have come back to us with positive feedback on the first two editions. As we said, we aim to make this Get your name on the list of winners publication what you want it to be, and again invite you to submit articles and information that you would like us to share with those who live locally. -

Datasheet Report: Envirocheck

Envirocheck ® Report: Datasheet Order Details: Order Number: 205627403_1_1 Customer Reference: NT12629 National Grid Reference: 358410, 560560 Slice: A Site Area (Ha): 7.1 Search Buffer (m): 1000 Site Details: W & M Thompson (Quarries) Ltd, Silvertop Quarry Hallbankgate BRAMPTON CA8 2PE Client Details: Ms F Reed Wardell Armstrong LLP City Quadrant 11 Waterloo Square Newcastle Upon Tyne NE1 4DP Order Number: 205627403_1_1 Date: 29-May-2019 rpr_ec_datasheet v53.0 A Landmark Information Group Service Contents Report Section Page Number Summary - Agency & Hydrological 1 Waste 22 Hazardous Substances - Geological 23 Industrial Land Use 30 Sensitive Land Use 32 Data Currency 33 Data Suppliers 39 Useful Contacts 40 Introduction The Environment Act 1995 has made site sensitivity a key issue, as the legislation pays as much attention to the pathways by which contamination could spread, and to the vulnerable targets of contamination, as it does the potential sources of contamination. For this reason, Landmark's Site Sensitivity maps and Datasheet(s) place great emphasis on statutory data provided by the Environment Agency/Natural Resources Wales and the Scottish Environment Protection Agency; it also incorporates data from Natural England (and the Scottish and Welsh equivalents) and Local Authorities; and highlights hydrogeological features required by environmental and geotechnical consultants. It does not include any information concerning past uses of land. The datasheet is produced by querying the Landmark database to a distance defined by the client from a site boundary provided by the client. In this datasheet the National Grid References (NGRs) are rounded to the nearest 10m in accordance with Landmark's agreements with a number of Data Suppliers. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for County Council Local Committee

Corporate, Customer and Community Services Directorate Legal and Democratic Services Cumbria House 117 Botchergate Carlisle CA1 1RD Tel 01228 606060 Email [email protected] 5 November 2018 To: The Chair and Members of the County Council Local Committee for Carlisle Agenda COUNTY COUNCIL LOCAL COMMITTEE FOR CARLISLE A meeting of the County Council Local Committee for Carlisle will be held as follows: Date: Tuesday 13 November 2018 Time: 10.00 am Place: Conference Room A/B, Cumbria House, Botchergate, Carlisle, CA1 1RD Dawn Roberts Executive Director – Corporate, Customer and Community Services NB THERE WILL BE A PRIVATE MEMBER BRIEFING ON THE RISING OF THE COMMITTEE REGARDING S106/DEVELOPER CONTRIBUTIONS Group Meetings: Labour: 9.00am Cabinet Meeting Room Conservative: 9.30am Conservative Group Office Independent: 9.00am Independent Meeting Room Enquiries and requests for supporting papers to: Lynn Harker Direct Line: 01228 226364 / 07825340229 Email: [email protected] This agenda is available on request in alternative formats Serving the People of Cumbria MEMBERSHIP Conservative (7) Labour (8) Independent Councillors (Non Aligned) (2) Mr GM Ellis Mr J Bell Mr RW Betton Mr LN Fisher Mrs C Bowditch Mr W Graham Dr S Haraldsen Ms D Earl Mrs EA Mallinson Dr K Lockney Mr J Mallinson (Vice-Chair) Mr A McGuckin Mr NH Marriner Mr R Watson Mrs V Tarbitt Mr SF Young Mr C Weber (Chair) Liberal Democrat (1) Mr T Allison ACCESS TO INFORMATION Agenda and Reports Copies of the agenda and Part I reports are available for members of the public to inspect prior to the meeting. -

Northumberland National Park Geodiversity Audit and Action Plan Location Map for the District Described in This Book

Northumberland National Park Geodiversity Audit and Action Plan Location map for the district described in this book AA68 68 Duns A6105 Tweed Berwick R A6112 upon Tweed A697 Lauder A1 Northumberland Coast A698 Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Holy SCOTLAND ColdstreamColdstream Island Farne B6525 Islands A6089 Galashiels Kelso BamburghBa MelrMelroseose MillfieldMilfield Seahouses Kirk A699 B6351 Selkirk A68 YYetholmetholm B6348 A698 Wooler B6401 R Teviot JedburghJedburgh Craster A1 A68 A698 Ingram A697 R Aln A7 Hawick Northumberland NP Alnwick A6088 Alnmouth A1068 Carter Bar Alwinton t Amble ue A68 q Rothbury o C B6357 NP National R B6341 A1068 Kielder OtterburOtterburnn A1 Elsdon Kielder KielderBorder Reservoir Park ForForestWaterest Falstone Ashington Parkand FtForest Kirkwhelpington MorpethMth Park Bellingham R Wansbeck Blyth B6320 A696 Bedlington A68 A193 A1 Newcastle International Airport Ponteland A19 B6318 ChollerforChollerfordd Pennine Way A6079 B6318 NEWCASTLE Once Housesteads B6318 Gilsland Walltown BrewedBrewed Haydon A69 UPON TYNE Birdoswald NP Vindolanda Bridge A69 Wallsend Haltwhistle Corbridge Wylam Ryton yne R TTyne Brampton Hexham A695 A695 Prudhoe Gateshead A1 AA689689 A194(M) A69 A686 Washington Allendale Derwent A692 A6076 TTownown A693 A1(M) A689 ReservoirReservoir Stanley A694 Consett ChesterChester-- le-Streetle-Street Alston B6278 Lanchester Key A68 A6 Allenheads ear District boundary ■■■■■■ Course of Hadrian’s Wall and National Trail N Durham R WWear NP National Park Centre Pennine Way National Trail B6302 North Pennines Stanhope A167 A1(M) A690 National boundaryA686 Otterburn Training Area ArAreaea of 0 8 kilometres Outstanding A689 Tow Law 0 5 miles Natural Beauty Spennymoor A688 CrookCrook M6 Penrith This product includes mapping data licensed from Ordnance Survey © Crown copyright and/or database right 2007. -

4 High Midgeholme, Midgeholme, Brampton, CA8

KING Estate Agents, Lettings & Valuers 4 High Midgeholme, Midgeholme, Brampton, CA8 7LT A charming & spacious end of terrace cottage with lovely private gardens, located in an area of outstanding beauty in the village of Midgeholme, approx 8 miles east of the market town of Brampton & within the catchment area of William Howard School, conservatory, sitting room with stone inglenook & multi-fuel stove, dining room, fitted kitchen, bathroom & separate shower room, 2 double beds to first floor. • Conservatory • Inner Hall • Shower Room • Sitting Room • Dining Room • 2 Bedrooms • Kitchen • Bathroom • Gardens & Parking Guide price £169,950 H&H King Ltd 12 Lowther Street, Carlisle, Cumbria CA3 8DA T: 01228 810799 E: [email protected] www.hhking.co.uk Registered in England No: 3758673. Registered Office: Borderway Mart, Rosehill, Carlisle, Cumbria CA1 2RS 4 High Midgeholme, Midgeholme, Brampton, CA8 7LT Ground Floor Conservatory 14'5 x 5'4 (4.39m x 1.63m) With tiled floor. 2 velux windows in sealed unit double glazing in wooden frame. Door to front. Double glass panelled doors to Sitting room. Sitting Room 15'8 x 11' (4.78m x 3.35m) Stone inglenook fireplace with stove cast iron gas fire . Radiator. Exposed Beams to ceiling. T.V aerial point. Door to dining room. Door to inner hallway and stairs off to first floor. Inner Hall With radiator. Bathroom 8'3 x 4'10 (2.51m x 1.47m) With a fitted 3 piece suite comprising low suite WC, wash hand basin and panelled bath. Radiator. Shower Room Shower cubicle with shower powered from the mains. -

Share Prospectus 2017

Hallbankgate Hub Ltd: A Community Benefit Society Share Offer You are invited to join a community enterprise providing a shop and cafe in Hallbankgate and a Hub for the village and the surrounding area. There has been a co-operative in the village of Hallbankgate for more than 130 years. It is part of the history and fabric of the village and has been a lifeline for many people. We want to continue this rich tradition of having a shop at the heart of the community. Scottish Midland Co-operative Society took ownership of the village shop in 2013 and closed it at the beginning of June 2015. Hallbankgate Hub Ltd, a Community Benefit Society set up by local people in 2015, then raised funds to buy the premises and re-open a shop combined with a café and community facilities in Hallbankgate. This now provides local residents with an attractive, friendly place that meets most of their shopping needs. By extending the services provided beyond those of a traditional Co-op we hope to ensure that the shop is viable and has a secure and certain future. The Hub is owned and controlled by the community through the Community Benefit Society. It can issue shares to ensure that everybody in the community who wishes can be a part-owner of the business and thus join in the process of deciding its development and its future. If you are not already a shareholder, the Management Committee of the Hub now invites you to buy shares for this purpose. This offer stands open indefinitely. -

Landscape Conservation Action Plan Part 1

Fellfoot Forward Landscape Conservation Action Plan Part 1 Fellfoot Forward Landscape Partnership Scheme Landscape Conservation Action Plan 1 Fellfoot Forward is led by the North Pennines AONB Partnership and supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund. Our Fellfoot Forward Landscape Partnership includes these partners Contents Landscape Conservation Action Plan Part 1 1. Acknowledgements 3 8 Fellfoot Forward LPS: making it happen 88 2. Foreword 4 8.1 Fellfoot Forward: the first steps 89 3. Executive Summary: A Manifesto for Our Landscape 5 8.2 Community consultation 90 4 Using the LCAP 6 8.3 Fellfoot Forward LPS Advisory Board 93 5 Understanding the Fellfoot Forward Landscape 7 8.4 Fellfoot Forward: 2020 – 2024 94 5.1 Location 8 8.5 Key milestones and events 94 5.2 What do we mean by landscape? 9 8.6 Delivery partners 96 5.3 Statement of Significance: 8.7 Staff team 96 what makes our Fellfoot landscape special? 10 8.8 Fellfoot Forward LPS: Risk register 98 5.4 Landscape Character Assessment 12 8.9 Financial arrangements 105 5.5 Beneath it all: Geology 32 8.10 Scheme office 106 5.6 Our past: pre-history to present day 38 8.11 Future Fair 106 5.7 Communities 41 8.12 Communications framework 107 5.8 The visitor experience 45 8.13 Evaluation and monitoring 113 5.9 Wildlife and habitats of the Fellfoot landscape 50 8.14 Changes to Scheme programme and budget since first stage submission 114 5.10 Moorlands 51 9 Key strategy documents 118 5.11 Grassland 52 5.12 Rivers and Streams 53 APPENDICES 5.13 Trees, woodlands and hedgerows 54 1 Glossary -

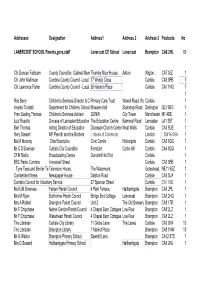

12 Appendix D 5 App C Lanercost Dist List

Addressee Designation Address1 Address 2 Address 3 Postcode No LANERCOST SCHOOL Parents,govs,staff Lanercost CE School Lanercost Brampton CA8 2HL 80 Cllr Duncan Fairbairn County Councillor, Cabinet Mem Thornby Moor House , Aikton Wigton , CA7 0JZ 1 Cllr John Mallinson Cumbria County Council -Local A17 Wolsty Close Carlisle CA3 0PB 1 Cllr Lawrence Fisher Cumbria County Council - Local 26 Hanson Place Carlisle CA1 1NG 1 1 Ros Berry Children's Services Director & CoPrimary Care Trust Wavell Road, RosCarlisle 1 Angela Tunstall Department for Children, SchoolsMowden Hall Staindrop Road Darlington DL3 9BG 1 Fran Gosling Thomas Children's Services Advisor GONW City Tower Manchester M1 4BE 1 Luiz Ruscillo Diocese of Lancaster Education The Education Centre Balmoral Road Lancaster LA1 3BT 1 Bert Thomas Acting Director of Education Diocesan Church Centre West Walls Carlisle CA3 8UE 1 Rory Stewart MP Penrith and the Borders House of Commons London SW1A 0AA 1 Ms M Mooney Chief Executive Civic Centre Rickergate Carlisle CA3 8QG 1 Mr C S Bowman Carlisle City Councillor Ferndale Corby Hill Carlisle CA4 8QG 1 CFM Radio Broadcasting Centre Durranhill Ind Est Carlisle 1 BBC Radio Cumbria Annetwell Street Carlisle CA3 8BB 1 Tyne Tees and Border Te Television House, The Watermark, Gateshead, NE11 9SZ 1 Cumberland News Newspaper House Dalston Road Carlisle CA5 5UA 1 Cumbria Council for Voluntary Service 27 Spencer Street Carlisle CA1 1BE 1 Ms KJM Bowness Farlam Parish Council 4 Park Terrace Hallbankgate Brampton CA8 2PL 1 Mrs M Ryan Burtholme Parish Council -

![[I] NORTH of ENGLAND INSTITUTE of MINING ENGINEERS TRANSACTIONS VOL. XI. 1861-2. NEWCASTLE-ON-TYNE: ANDREW REID, 40 & 65, PI](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8169/i-north-of-england-institute-of-mining-engineers-transactions-vol-xi-1861-2-newcastle-on-tyne-andrew-reid-40-65-pi-2388169.webp)

[I] NORTH of ENGLAND INSTITUTE of MINING ENGINEERS TRANSACTIONS VOL. XI. 1861-2. NEWCASTLE-ON-TYNE: ANDREW REID, 40 & 65, PI

[i] NORTH OF ENGLAND INSTITUTE OF MINING ENGINEERS TRANSACTIONS VOL. XI. 1861-2. NEWCASTLE-ON-TYNE: ANDREW REID, 40 & 65, PILGRIM STREET. 1862. [ii] NEWCASTLE-UPON-TYNE: PRINTED BY ANDREW REID, 40 & 65, PILGRIM STREET. [iii] INDEX TO VOL. XI. A Arrangement with Natural History Society........ 4 Atkinson, J. J., on Close-Topped Tubbing .. .. .. 8 Atkinson, J. J., on Fan Ventilation .. .. .. .. .. 89 Albert, late Prince Consort, Letter as to .. .. .. 99 Atkinson, J. J., on Coal Formations.. .. .. .. 141 Abbot's Safety-Lamp .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 160 Aubin Coal-Field .............. 168 Analyses of Peat, Lignite, and Coal.. .. .. .. 171 Anthracite, how formed .. .. .. .. 172 Aluminium, Experiments on .. .. .. .. .. 178 Archerbeckburn Permian Formation.. .. .. 189 Aspatria, Cessation of Coal at .. .. .. .. 180 B Binney, Mr., on Iron Exposed to Acid .. .... .. 22 Boutigny on Boiler Accidents .. .. .. 43 Berwick Coal Measures . .. .. .. .. 103 Basalt Bed, Northumberland.. .. .. .. .. 129 Beam at Hartley, Weight of.. .. .. .. 153 Bitumen, how produced .. .. .. 171 Brown's Evidence—Seaton Burn Accident .. .. .. 35 Bowman's Evidence—Seaton Burn Accident .. .. 33 C Coulson, Wm., on Close-Topped Tubbing .. .. .. 8 Clapham, Mr., his Analysis of Iron Tubbing .. .. .. 20 Calvert, Professor, on Iron exposed to Acid .. .. .. 21 Clapham, Mr., on preserving Stone from Acid .. .. 25 Crone, Stephen C., on Boiler Explosions .. .. .. 27 [iv] Coulson, Mr., at New Hartley .......... 148 Carbonic Oxide at New Hartley .. .. .. .. .. 150 Calamites forming Coal .. .. .. .. .. 173 Carboniferous Limestone—Cumberland .. .. .. 188 Cheviot Range, when protruded .. .. .. 118 200 202 Cheviot Porphyritic Rock, its effect .. .. .. .. 118 Coquet Mouth, Coal at .. .. .. .. .. .. 115 D Daglish, John, on the Action of Furnace Gases .. .. 19 Daniel on Iron exposed to Acid .. .. .. .. 20 Drift or Boulder Clay, Cumberland .. .. .. .. .. 85 Devonian Formation, Northumberland . -

Annual Report 2016

14 King’s Head Court, Bridge Street, APPLEBY, Cumbria, CA16 6QH Tel: 01768 353954 email: [email protected] Every Story I Have Ever Told is Part ofEvery I Told Part Ever is Have Me, Claire Peach Story Annual Report 2016 – 2017 Highlights is supported by: 1 Contents Contents Section Page 1 Summary 3 2 Highlights’ Vision statement 3 3 Fact File 3 4 Projects and Development Work 5 5 Contemporary Craft Tour Winter 2016 9 6 Training & Marketing 10 7 Workshop Programme 12 8 Future Plans 13 9 Company Details 13 Appendices Venues 2016-17 14 Programme, Artists, Companies 2016-17 15 Show Comments 16 Web Site data 17 Map of live venues 18 Performances & workshops: Data breakdown 19 -33 ‘Mavis Sparkle’, M6 Theatre Company – Autumn 2016 2 1 SUMMARY This report reviews the activities and plans of Highlights Rural Touring Scheme for the period 1 April 2016 to 31 March 2017. 2016/17 was the second year of the National Portfolio Organisation [NPO] 3 year agreement with Arts Council England [ACE]. The NPO agreement is awarded to Highlights [H] and Arts Out West [AOW] together, with Highlights as the lead partner. The level of the award represents a standstill arrangement (in relation to the 2015-16 amount received). Local Authority funding from County Durham and Northumberland overall remained at a standstill amount; and the amount from Cumbria was cut in its entirety. The Management Committee started and ended the year with six members. Over the course of the year, Geoff Hoskin resigned as Chair; and John Holland was elected as his replacement. -

Application Reference No. 1/19/9009. Proposal

DEVELOPMENT CONTROL AND REGULATION COMMITTEE 31 October 2019 A report by the Acting Executive Director - Economy and Infrastructure _____________________________________________________________________ Application Reference No. 1/19/9009 Application Type: Full Planning Permission Proposal: Change of use to allow imported inert material (construction, demolition and excavation waste) to be screened and processed Location: Silvertop Quarry, Hallbankgate, Brampton, Cumbria Applicant: Thompsons of Prudhoe Ltd Date Valid: 1 August 2019 Reason for Committee Level Decision: Renewal of time limited planning permission. _____________________________________________________________________ 1.0 RECOMMENDATION 1.1 That planning permission be GRANTED subject to conditions set out in Appendix 1 to this report. 2.0 THE PROPOSAL 2.1 Planning permission is sought for change of use to allow imported material (construction, demolition and excavation waste) to be screened and processed, within the quarry void. Planning permission (1/08/9029) was granted on 17 December 2008 to allow “recycling facilities for inert material” - planning permission was granted for a period of 10 years expiring on 16 December 2018. Unfortunately, Thompsons of Prudhoe hadn’t realised the planning permission had lapsed, hence the need now to reapply for full planning permission. 2.2 The site for use is a recycling area of 0.9 ha set within Silvertop Quarry. The application site is at the base of the current void space on the southern boundary of the site. Silvertop Quarry is an active quarry with planning permission expiring in 2042 (1/97/9021). 2.3 Planning permission 1/08/9029 provided a justification for need, that material was being taken to Thompson’s of Prudhoe other licensed premises at Corbridge Northumberland (approximately 30 miles each way) for processing and then returned back to Silvertop Quarry as engineering fill and quality top soil. -

UK Coal Resource for New Exploitation Technologies Final Report

UK Coal Resource for New Exploitation Technologies Final Report Sustainable Energy & Geophysical Surveys Programme Commissioned Report CR/04/015N BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Commissioned Report CR/04/015N UK Coal Resource for New Exploitation Technologies Final Report *Jones N S, *Holloway S, +Creedy D P, +Garner K, *Smith N J P, *Browne, M.A.E. & #Durucan S. 2004. *British Geological Survey +Wardell Armstrong # Imperial College, London The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number GD 272191/1999 Key words Coal resources, UK, maps, undergound mining, opencast mining, coal mine methane, abandoned mine methane, coalbed methane, underground coal gasification, carbon dioxide sequestration. Front cover Cleat in coal Bibliographical reference Jones N S, Holloway S, Creedy D P, Garner K, Smith N J P, Browne, M.A.E. & Durucan S. 2004. UK Coal Resource for New Exploitation Technologies. Final Report. British Geological Survey Commissioned Report CR/04/015N. © NERC 2004 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2004 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] The London Information Office maintains a reference collection www.bgs.ac.uk of BGS publications including maps for consultation. Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA Desks.