REPORTS PATENT, DESIGN, and TRADE MARK Casesr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Electrician 3Rd Semester - Module 1 : DC Generator

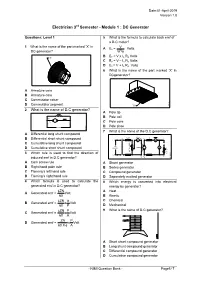

Electrician 3rd Semester - Module 1 : DC Generator Questions: Level 1 5 What is the formula to calculate back emf of a D.C motor? 1 What is the name of the part marked ‘X’ in V A Eb = Volts DC generator? IaRa B Eb = V x Ia Ra Volts C Eb = V – Ia Ra Volts D Eb = V + Ia Ra Volts 6 What is the name of the part marked ‘X’ in DCgenerator? A Armature core B Armature core C Commutator raiser D Commutator segment 2 What is the name of D.C generator? A Pole tip B Pole coil C Pole core D Pole shoe 7 What is the name of the D.C generator? A Differential long shunt compound B Differential short shunt compound C Cumulative long shunt compound D Cumulative short shunt compound 3 Which rule is used to find the direction of induced emf in D.C generator? A Cork screw rule A Shunt generator B Right hand palm rule B Series generator C Fleming’s left hand rule C Compound generator D Fleming’s right hand rule D Separately excited generator 4 Which formula is used to calculate the 8 Which energy is converted into electrical generated emf in D.C generator? energy by generator? φZN A Heat A Generated emf = Volt 60 B Kinetic φZN A C Chemical B Generated emf = x Volt 60 P D Mechanical φZN P 9 What is the name of D.C generator? C Generated emf = x Volt 60 A ZN P D Generated emf = x Volt 60 X φ A A Short shunt compound generator B Long shunt compound generator C Differential compound generator D Cumulative compound generator - NIMI Question Bank - Page1/ 7 10 What is the principle of D.C generator? 14 How many parallel paths in duplex lap A Cork screw rule winding -

7. (4-Fc- 1 by (24-4-2

No. 787,302, PATENTED APR, l905. M, C. A. LATOUR SINGLE PHASE DYNAMO ELECTRIC MACHINE, APPLICATION FILED AUG, 30, 1904, Witnesses. Inventor 3262.2%.-- a 322e. Marius C.A. Otour. 7. (4-f-c- 1 by (24-4-2------39tt'U. No. 787,302, Patented April 11, 1905. UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. MARIUS CHARLS ARTHUR LATOUR, OF PARIS, FRANCE, ASSIGNOR TO GENERAL ELECTRIC COMPANY., A CORFORATION OF NEW YORK. SNGLE-FHASE DYNAMOELECTRIC MACH NE. SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 787,302, dated April 11, 1905. Application filed August 30, 1904, Serial No. 222,683. To all, Luhon, it notif concern: in inductive relation to the armature to act as Be it known that I, MARIUS CHARLS AR damping-windings for damping out the fluc THUR LATOUR, a citizen of France, residing at tuations, and this arrangement has improved Paris, Department of Seine, France, have in the operation of the machines. vented certain new and useful Improvements My invention consists in providing a novel in Single-Phase Dynamo-Electric Machines, form of field-winding and connections there of which the following is a specification. for, such that the field-winding itself may act 55 My invention relates to single-phase alter as a damping-winding. nating-current machines of the type having a More specifically considered, my invention IO field-magnet excited with direct current, and consists in providing the armature with a dis has particular reference to single-phase rotary tributed field-winding instead of the usual converters, though it is not limited to this par polar winding and short circuiting equipoten ticular application. -

Using Passive Elements and Control to Implement Single-To Three-Phase

LINEAR LIBRARY C01 0072 5350 1111111111111111 University of Cape Town Electrical Engineering Dept Power Electronics Group ' Using Passive Elements and Control to Implement Single- to Three-Phase Conversion University of Cape Town Prepared by: Stuart Marinus University of Cape Town South Africa Prepared for: Mr. M. Malengret Department of Electrical Engineering University of Cape Town Due Date: 30 Septem her 1999 Acknowledgments I wish to thank the following people for their invaluable contribution towards this project: Mr M. Malengret, my thesis supervisor, for helping me a great deal with the initial formulation of ideas and making it possible for me to complete my Master of Science Degree at the University of Cape Town. My parents, Shirley and Andy, for sacrificing so much for me. Their unconditional love and belief in me has made it possible for me to get this far. Caroline, for her support, understanding and thoughtfulness. Dan Archer, who gave up much of his time, knowledge and experience on a daily basis, especially in the design of the saturable-core reactors and switch-mode power supplies. Clive Granville for his advice and excellent technical assistance. The research group: Huey, Dave, Elvis, Dan, Sven and Kurt, and staff and students of the Power Machines Laboratory- Chris, Clive, Brian, Colin and Phineas who were always ready and willing to help when needed and who made my time spent at UCT very enjoyable. II Terms of Reference This thesis was commissioned and supervised by Mr Malengret of the Electrical Engineering Department at the University of Cape Town in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a MSc Degree in Electrical Engineering. -

Multiple Choice Practice Questions for ONLINE/OMR AITT-2020 2 Year

Multiple Choice Practice Questions for ONLINE/OMR AITT-2020 nd 2 Year Electrician Trade Theory DC machine (Generator & Motor) 1 What is the name of the part marked as ‘X’ in DC generator given below? A - Armature core B -Brush C- Commutator raiser D -Commutator segment 2 What is the name of D.C generator given below? A- Differential long shunt compound B- Differential short shunt compound C -Cumulative long shunt compound D -Cumulative short shunt compound 3 Which rule is used to find the direction of induced emf in D.C generator? A- Cork screw rule B -Right hand palm rule C -Fleming’s left-hand rule D -Fleming’s right hand rule 4 Which formula is used to calculate the generated emf in D.C generator? A –ZNPa/60ɸ B -ɸZna/60P C - ɸZnp/60a D - ɸZnp/60 5 What is the formula to calculate back emf of a D.C motor? A -Eb = V/Ia Ra B- Eb = V x Ia Ra C -Eb = V – Ia Ra D -Eb = V + Ia Ra 6 What is the name of the part marked ‘X’ in DC generator given below? A -Pole tip B -Pole coil C -Pole core D -Pole shoe 7 What is the name of the D.C generator given below? A -Shunt generator B -Series generator C- Compound generator D -Separately excited generator 8 Which energy is converted into electrical energy by generator? A -Heat B- Kinetic C -Chemical D -Mechanical 9 What is the name of D.C generator field given below? A -Short shunt compound generator B -Long shunt compound generator C -Differential compound generator D -Cumulative compound generator 10 What is the principle of D.C generator? A -Cork screw rule B -Fleming’s left-hand rule C -Fleming’s -

Testing a Rotary Converter

TUES IS P Testing a Rotary Converter Submitted to the Faculty of the OREGOi AGRICULTURAL COLLEGE for the decree of BACHELOR OF SCIEITCE In ELECTRICAL EITGIITEERIJTG by Julius Gordon Wallace Going June 1, 1910 APPROVE1.. Redacted for privacy - - -se-fl n- - as 4,. .c n a a s _- - - f.rteflt of Electrical ErÀginoerir.g. Redacted for privacy - - Lcaì; School ninoeriLg. ROTARY COI7EiTii. The ROTARY COLVEiTER or 1'ouilo Current Gexierator Is a machine for convert1g alterLatinC currcr1t to dir- oct current, or vice vora. The thrortarce that such machines have iow asu.rne in the e1octric1 industry is clue to severci CUiSeS; (a) It is tecocsary, for ccorornic roisons, to use alter- r.atin currett at high voltacs lt 1otg-distaice trans- mission. Therefore, rotar; converters are re.ired for char..ing the alterr4eting currert into direct current for use IL olectrie railway motors, wi:lch riuRt be supjüied with direct current from the trolley wire at po1rts at a a1starce from the 1;ower house. (b) :otary converters are needed for charging storage batteries in plces where the cer.tru1 statioL supiios, elternating current and inverted rotaries are necessary for factory driving vith alternating current r'iotors in caces where direct current ordy Ic supplied by contrai etat Ions. (o) Direct current is r.ecesear In many chemical and. eloctrometallurgical thduutrles euch as electrolytic re- duction of alumlnwn froT It oree, electrolytic refining of copper, etc. If alternating current Is generated and transmitted to these octablishments It must be converted into direct current before It can te utilized. -

Commissioning a 400 Hz Rotary Inverter

Commissioning a 400 Hz Rotary Inverter Wayne Anthony Smith A dissertation submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Cape Town, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Engineering. Cape Town, January 2009 Declaration I know the meaning of plagiarism and declare that all the work in the document, save for that which is properly acknowledged, is my own. SignatureofAuthor.................................. ............................ 11 January 2009 i Abstract This dissertation covers the commissioning and testing of an aircraft’s constant frequency alternator as the power supply for the Blue Parrot radar. The Blue Parrot is an X-band radar which forms part of the navigation and weapon-aiming system onboard the Buccaneer S-50 SAAF aircraft. The radar set uses a source of three-phase power at 400 Hz, which the constant frequency alternator can supply with the aid of certain auxiliary systems. The auxiliary systems include a prime mover, blower fan and a telemetering system. The prime mover has high starting currents which were reduced significantly by the use of a soft-starter. During testing, the constant frequency alternator started overheating and a blower fan was selected based on its thermal requirements. Significant cooling of the constant frequency alternator’s case temperature was achieved by the use of a blower fan and shroud. The generator control unit monitors and regulates all parameters on the unit except for case temperature and blower fan pressure. A telemetering system was designed and built to monitor and display these parameters. ii Acknowledgements Thank you LORD a second time. I would also like to express my appreciation to those who helped me achieve this mile- stone. -

Written Pole Motors

PDHonline Course E299 (3 PDH) Written Pole Motors Instructor: Lee Layton, PE 2012 PDH Online | PDH Center 5272 Meadow Estates Drive Fairfax, VA 22030-6658 Phone & Fax: 703-988-0088 www.PDHonline.org www.PDHcenter.com An Approved Continuing Education Provider www.PDHcenter.com PDH Course E299 www.PDHonline.org Written Pole® Motors Lee Layton, P.E Table of Contents Section Page Introduction ………………………………………… 3 I. Basic Operation of Electric Motors ……………… 5 II. Written Pole Motor Design ……………………… 20 III. Operational Benefits of Written-Pole® Motors …. 26 Summary ..…………………………………………. 30 The term Written-Pole® motor is trademarked by Precise Power Corporation of Bradenton, Fl. All references in this course to Written-Pole motors refer to the trademarked name registered to Precise Power Corporation. © Lee Layton. Page 2 of 30 www.PDHcenter.com PDH Course E299 www.PDHonline.org Introduction In the 1990’s, with support from the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), the Precise Power Corporation of Bradenton, Florida, developed a new concept in electric motors called the Written Pole® electric motor. This new motor type dramatically reduces starting currents of single phase motors and allows the design of single phase motors up to 100 hp as compared to conventional single phase motors, which are generally limited to units of 15 hp and smaller. Electric motors are the backbone of an electrified society and electric motors are responsible for two-thirds of all electric energy generated in the United States today. Most electric motors are small and only 2% of the motors in the United States are over 5 hp, but they account for over 70% of the energy used to drive electric motors. -

Appropriate Size D.C

Appropriate Size D.C. Power Supplies For Heritage Electric Tramways Richard Clarke BE MEngSc MIEAust MIEEE Chief Engineer, Sydney Tramway Museum Introduction Tramway museums have rather small electric traction power supply requirements compared with the former city systems that they are displaying. Much of their former systems D.C. rectifying equipment is unsuitable in many regards for museum use. In the early days (c1960) of the tramway museum movement in Australasia (and U.K.) provision of a traction power supply was the single greatest barrier to operation. Most tramway museums have solved their power supply requirements, but it is worth restating the characteristics for future projects. Initial museum power supplies Sydney Tramway Museum It is worth going through Sydney Tramway Museums experience as STM was the first museum to power up in Australia. At the closure of the Sydney Tramways virtually all of the traction substations were rotary converters fed by 6.6kV feeders at 25Hz (then known as 25 cycles per second). The 25Hz generation at Ultimo and White Bay powerhouses then closed down. The only two possibilities for former government tramways substations were Waterloo mercury arc substation and Kogarah trolley rotary converter substation which were the standard 50Hz Waterloo was not available as it was used to supply D.C. to the remaining Randwick Workshops, it was 5kV supply, the supply available at Sydney Tramway Museum was 11kV so that Waterloo was not in any case suitable. One of the two Kogarah 500kW Rotary Converters was purchased and transported to STM. A brick building was constructed and the rotary converter and switchgear put in place. -

Optimization of Phase Converter Parameters and Effects of Voltage Variation on Their Performance Roshan Lal Chhabra Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1974 Optimization of phase converter parameters and effects of voltage variation on their performance Roshan Lal Chhabra Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Agriculture Commons, and the Bioresource and Agricultural Engineering Commons Recommended Citation Chhabra, Roshan Lal, "Optimization of phase converter parameters and effects of voltage variation on their performance " (1974). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 5978. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/5978 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. -

Witnesses, Inventor. -4 N.-46 (0

No. 701,958, Patented June 10, 1902. C. P. STEINMETZ. AUTOMATC CUT OUT. (Application filed Mar. 6, 1899.) (No Model.) a. J k Witnesses, Inventor. -4 N.-46 (0. Cls O Steinmetz 4,5404 by 4.40als.J4tty. UNITED STATES PATENT OFFICE. CHARLES P. STEINMETZ, OF SCHENECTADY, NEW YORK, ASSIGNOR TO GENERAL ELECTRIC COMPANY, A CORPORATION OF NEW YORK. AUTOMATIC CUT OUT. SPECIFICATION forming part of Letters Patent No. 701,958, dated June 10, 1902. Application filed March 6, 1899, Serial No. 707,880, (No model.) To all tuh-On, it may concert: inverted by normally Supplying the same Beitknown that I, CHARLES P. STEINMETZ, with direct current and deriving alternating a citizen of the United States, residing at currents therefrom, the speed of the machine Schenectady, county of Schenectady, State of is varied not only by changes in electromotive New York, have invented certain new and force of the direct current supplied, but also 55 usefulmprovements in Automatic Cut-Outs, by changes in the character of the load on the (Case No. 1,037,) of which the following is a alternating - current end of the machine. specification. - Thus if an inductive load is fed from the al In the practical operation of rotary con ternating mains the lagging currents pro IO verters I have found it desirable to provide duced thereby react upon the field-magnets Some automatically-actuated means for cut of the rotary converter and cause a weaken ting the machine out of circuit or otherwise ing of the same, the immediate result of which reducing its speed upon a predetermined rise is a speeding up of the rotary converter, in speed-as, for example, twenty per cent. -

Commercial Dynamo Design

O RI GINA L PA PE RS COMMERCI AL DYNA MO DES I GN W I LLIA M L WAT E RS M E E H . , . , . En inccr in ( Mar : o Hi /x S eed M ac/tinn Westin nause Elec i g y f g p y, g tr c 65 u r r /zi E er N t o l lec Man actu in Co . rme / C c n ine a i na E f g fi y f g , o l rin /r u r C . and Co nsu tin En ineer Wa o se Ai , g g , g Brake and Canadian Westing/ww e Co t . F I R S T E D I T I O N NEW O Y RK. $OHN W ILEY 8c SONS LONDON: C HA PMA N 8c H A LL, 1.1m m 1911 COPYRIGHT 19 11 BY W I I W A T ERS LL A M L. n t kno w led e but i no ra ncc tlla t bc m o g , g , g C HA RLES DARWIN cfzm ma n a debto r to Ii i: ro u io n y p fe , ; b a l mend to e he p and orna ment tbcrcunto . Fu ncns BA CON 3 4 36 52 I NT R ODUC T I ON — Commercial Engi neering The nin eteenth century was nota s i ble for the achievement of the eng neer , and there is little doubt that the men responsible for this pioneer w o rk were engineers in i the broades t sense of the word . -

Theory and Construction of a Rotary Converter

VI.R.1-1 'La RS9.LCMY. FA.FMktz-og. The Theory and Construction of a Four Kilowatt Rotary Converter. For the sake of simplicity we will teke a special case and extend it to the general. Suppose we have a closed. coil. bipolar direct current generator. If we connect three leads to the com- mutator at equidistant points around-its circumference, i.e. 120 mechanical degrees apart and these in turn be connected to three slip rings, disregarding the commutator and supposing the machine to be separately excited, we wile have a simple three phase closed delta connection. Now if this were driven by external power it would. generate three phase current. Taking the current to excite the field from the commutator will have no effect on this connection. If alternating current be impreatd upon the slip rings the machine will operate as a ',..nchronous leotar but as stated 'eefore we started with a direct current generator an as the armature is revolving in a field. if a load were connected across the brushes it eould operate as direct current generator. This is the principle upon which all rotary converters are based. If the numbers of poles were increased. the construction would have to be altered. by tapp- ing at every 1.!70 electric& c eermes insteadce!" mechanical degrees. ihese are to be connected in the proper order to the original three slip rings. Thus for an N pole converter, where N is the number of poles, therewculd be three teps for every pair of poles or 7N/X taps.