CHINESE VIEWS ANI) PERSPECTIVES Lee Kam Hing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bpalive2012 Compile Web.Pdf

2012 Disclaimer No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted by any or other means, including electronic, mechanical or photocopying or in any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of BP Healthcare Group. About a year ago(2003), I was diagnosed with cancer. I had a scan at 7:30 in “the morning, and it clearly showed a tumour on my pancreas. I didn't even know what a pancreas was. All the doctors told me was that this was almost certainly a type of cancer that is incurable, and that I should expect to live no longer than three to six months." Later that evening, I had a biopsy, where they inserted an endoscope down “my throat, through my stomach and into my intestines, put a needle into my pancreas and removed a few cells from the tumour. I was sedated, but my wife, who was there, told me that when they viewed the cells under a microscope the doctors started crying because it turned out to be a very rare form of pancreatic cancer that is curable with surgery. I had the surgery and I'm fine now." If it wasn't for the wonders of health screening, diagnosis and treatment, Jobs would not be able to introduce iPhone 3G on June 9, 2008, new iPod media players on Sept 9, 2008, and unveil a lighter MacBook Air laptop on Oct 20, 2010 Source: http://news.stanford.edu/news/2005/june15/jobs-061505.html http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-01-17/steve-jobs-s-health- reports-since-his-cancer-diagnosis-in-2003-timeline.html Steve Jobs 1955-2011 Contents History 1-2 Corporate Structure 3 Board Of Directors -

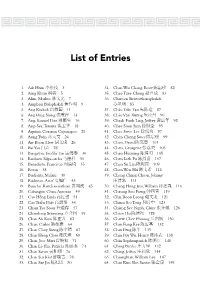

List of Entries

List of Entries 1. Aik Htun 3 34. Chan Wai Chang, Rose 82 2. Aing Khun 5 35. Chao Tzee Cheng 83 3. Alim, Markus 7 36. Charoen Siriwatthanaphakdi 4. Amphon Bulaphakdi 9 85 5. Ang Kiukok 11 37. Châu Traàn Taïo 87 6. Ang Peng Siong 14 38. Châu Vaên Xöông 90 7. Ang, Samuel Dee 16 39. Cheah Fook Ling, Jeffrey 92 8. Ang-See, Teresita 18 40. Chee Soon Juan 95 9. Aquino, Corazon Cojuangco 21 41. Chee Swee Lee 97 10. Aung Twin 24 42. Chen Chong Swee 99 11. Aw Boon Haw 26 43. Chen, David 101 12. Bai Yao 28 44. Chen, Georgette 103 13. Bangayan, Teofilo Tan 30 45. Chen Huiming 105 14. Banharn Silpa-archa 33 46. Chen Lieh Fu 107 15. Benedicto, Francisco 35 47. Chen Su Lan 109 16. Botan 38 48. Chen Wen Hsi 111 17. Budianta, Melani 40 49. Cheng Ching Chuan, Johnny 18. Budiman, Arief 43 113 19. Bunchu Rotchanasathian 45 50. Cheng Heng Jem, William 116 20. Cabangon Chua, Antonio 49 51. Cheong Soo Pieng 119 21. Cao Hoàng Laõnh 51 52. Chia Boon Leong 121 22. Cao Trieàu Phát 54 53. Chiam See Tong 123 23. Cham Tao Soon 57 54. Chiang See Ngoh, Claire 126 24. Chamlong Srimuang 59 55. Chien Ho 128 25. Chan Ah Kow 62 56. Chiew Chee Phoong 130 26. Chan, Carlos 64 57. Chin Fung Kee 132 27. Chan Choy Siong 67 58. Chin Peng 135 28. Chan Heng Chee 69 59. Chin Poy Wu, Henry 138 29. Chan, Jose Mari 71 60. -

THE RISE and FALL of DR LING LIONG SIK (Bernama 23/05/2003)

23 MAY 2003 Ling-Politics THE RISE AND FALL OF DR LING LIONG SIK By: Alan Ting KUALA LUMPUR, (Bernama) - He was not seen as a likely presidential candidate of the MCA during the infamous clash between Datuk Dr Neo Yee Pan and Datuk Tan Koon Swan in the 1980s. Having thrown his weight behind Koon Swan, he was like any other "generals" in the bitter party tussle, till a twist of fate propelled him to the helm of the oldest and biggest Chinese party, a job he held for almost 17 years. That twist of fate came on Sept 3, 1986 when he, as the deputy president, was appointed to the top post, replacing Koon Swan who had to resign after being sentenced to a two-year jail and a fine of S$500,000 for criminal breach of trust in Singapore. Born on Sept 18, 1943, Dr Ling had his early education at the King Edward VII School in Taiping before joining the prestigious Royal Military College (RMC) in Sungai Besi. From the RMC, Dr Ling studied medicine at the University of Singapore in 1961 and by 1966, he served as a doctor at Penang General Hospital before opting for private practice in Butterworth in 1975. The medical doctor, with a dead-pan face and gravel voice, launched his political career in 1968 when he joined the MCA and worked his way up to become a Central Committee member in 1974. EARLY YEARS In the same year, he was picked to stand in the Mata Kuching (now called Bagan) parliamentary constituency on an MCA ticket and won, retaining the seat for two subsequent terms. -

Peny Ata Rasmi Parlimen

Jilid 1 Harl Khamis Bil. 68 15hb Oktober, 1987 MAL AYSIA PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DEWAN RAKYAT House of Representatives P ARLIMEN KETUJUH Seventh Parliament PENGGAL PERTAMA First Session KANDUNGANNYA JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MULUT BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN [Ruangan 11433] USUL-USUL: Akta Acara Kewangan 1957- Menambah Butiran Baru "Kumpulan Wang Amanah Pembangunan Ekonomi Belia", dan "Tabung Amanah Taman Laut dan Rezab Laut" [Ruangan 11481] Akta Persatuan Pembangunan Antarabangsa 1960-Caruman Malaysia [Ruangan 11489] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Kumpulan Wang Amanah Negara [Ruangan 11492] Dl(;ETA� OLEH JABATAN P1UlC£TAJtAN NEGARA. KUALA LUMPUR HA.JI MOKHTAR SMAMSUDDlN.1.$.D., S,M,T., $,M.S., S.M.f'., X.M.N., P.l.S., KETUA PS.NOAK.AH 1988 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT YANG KETUJUH Penyata Rasmi Parlimen PENGGAL YANG PERTAMA AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, TAN SRI DATO' MOHAMED ZAHIR BIN HAJI ISMAIL, P.M.N., S.P.M.K., D.S.D.K., J.M.N. Yang Amat Berhormat Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Dalam Negeri dan Menteri Kehakiman, DATO' SERI DR MAHATHIR BIN MOHAMAD, s.s.D.K., S.S.A.P., S.P.M.S., S.P.M.J., D.P., D.U.P.N., S.P.N.S., S.P.D.K., s.P.C.M., s.s.M.T., D.U.N.M., P.1.s. (Kubang Pasu). Timbalan Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Pembangunan Negara " dan Luar Bandar, TUAN ABDUL GHAFAR BIN BABA, (Jasin). Yang Berhormat Menteri Pengangkutan, DATO DR LING LIONG SIK, D.P.M.P. (Labis). Menteri Kerjaraya, DATO' S. -

A Study on Interruptions by the Chairperson in the Dewan Rakyat

ACCOUNTABILITY IN THE PARLIAMENT OF MALAYSIA: A STUDY ON INTERRUPTIONS BY THE CHAIRPERSON IN THE DEWAN RAKYAT Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität zu Bonn vorgelegt von Nor Azura binti A Rahman aus Johor, Malaysia Bonn 2021 Gedruckt mit der Genehmigung der Philosophischen Fakultät der Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn Zusammensetzung der Prüfungskommission: Prof. Dr. Stephan Conermann (Vorsitzende/Vorsitzender) Prof. Dr. Christoph Antweiler (Betreuerin/Betreuer und Gutachterin/Gutachter) Prof. Dr. Claudia Derichs (Gutachterin/Gutachter) Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 26 November 2020 i ABSTRACT The election of the chairman of the House of Representatives, a chamber of the Malaysian parliament, has always been determined by the ruling party. The centralization of executive power has also absorbed the function of the chairman, so that the chairman acts partisanly in parliamentary debates. Also, the chairman has developed into an institution that carries out agenda-setting within the framework of the parliament. This raises the conceptual question of whether legislation in Malaysia is still performed independently by the parliament. The observed patterns require an attempt to re-conceptualize the roles as well as the assigned meaning of various expressions of parliamentary routine, including those that are unwritten and informal, for instance those which can also be termed “subjective forms of rule” at one's own discretion. In my doctoral thesis, I apply an interdisciplinary analytical framework that relates to accountability studies, as well as micro- sociological direct interaction, the interpretations of procedural interactions in conversation, as well as studies of political discretion in parliamentary operations. My main research question asks how the Speaker of Parliament fulfils his responsibilities by disrupting ongoing parliamentary debates. -

(Company No: 50948-T) Incorporated in Malaysia CONTENTS

(Company No: 50948-T) Incorporated in Malaysia CONTENTS METRO KAJANG HOLDINGS BERHAD 2 • Notice of Annual General Meeting (Company No.50948-T • Incorporated in Malaysia) 4 • Statement on Particulars of Directors 7 • Corporate Information 8 • Chairman’s Statement 10 • Director’s Profile 13 • Corporate Governance 20 • Audit Committee 24 • Directors’ Report 30 • Statement by Directors 30 • Statutory Declaration 31 • Report of the Auditors to the Members 32 • Balance Sheets 34 • Income Statements 35 • Statements of Changes in Equity 37 • Cash Flow Statements 39 • Notes to the Financial Statements 74 • List of Properties 78 • Statistics of Shareholdings Form of Proxy METRO KAJANG HOLDINGS BERHAD (Company No.50948-T • Incorporated in Malaysia) Notice of Annual General Meeting NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN THAT the Twenty-Second Annual General Meeting of METRO KAJANG HOLDINGS BERHAD will be held at Ballroom, First Floor, Metro Inn, Jalan Semenyih, 43000 Kajang, Selangor Darul Ehsan on Wednesday, 30 January 2002 at 10.00 a.m. to transact the following business: ORDINARY BUSINESS: 1. To receive the Audited Accounts for the year ended 30 September 2001 together with the Directors’ and Auditors’ reports thereon. (ORDINARY RESOLUTION 1) 2. To approve the payment of a First and Final Tax Exempt dividend of 3.5% per share for the year ended 30 September 2001. (ORDINARY RESOLUTION 2) 3. To approve Directors’ fees amounting to RM32,000-00 for the year ended 30 September 2001. (ORDINARY RESOLUTION 3) 4. To re-elect the following Directors who retire in accordance with the Company’s Articles of Association and being eligible, offer themselves for re-election. -

The Chinese Education Movement in Malaysia

INSTITUTIONS AND SOCIAL MOBILIZATION: THE CHINESE EDUCATION MOVEMENT IN MALAYSIA ANG MING CHEE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2011 i 2011 ANG MING CHEE CHEE ANG MING SOCIAL MOBILIZATION:SOCIAL INSTITUTIONS AND THE CHINESE EDUCATION CHINESE MOVEMENT INTHE MALAYSIA ii INSTITUTIONS AND SOCIAL MOBILIZATION: THE CHINESE EDUCATION MOVEMENT IN MALAYSIA ANG MING CHEE (MASTER OF INTERNATIONAL STUDIES, UPPSALA UNIVERSITET, SWEDEN) (BACHELOR OF COMMUNICATION (HONOURS), UNIVERSITI SAINS MALAYSIA) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2011 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My utmost gratitude goes first and foremost to my supervisor, Associate Professor Jamie Seth Davidson, for his enduring support that has helped me overcome many challenges during my candidacy. His critical supervision and brilliant suggestions have helped me to mature in my academic thinking and writing skills. Most importantly, his understanding of my medical condition and readiness to lend a hand warmed my heart beyond words. I also thank my thesis committee members, Associate Professor Hussin Mutalib and Associate Professor Goh Beng Lan for their valuable feedback on my thesis drafts. I would like to thank the National University of Singapore for providing the research scholarship that enabled me to concentrate on my thesis as a full-time doctorate student in the past four years. In particular, I would also like to thank the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences for partially supporting my fieldwork expenses and the Faculty Research Cluster for allocating the precious working space. My appreciation also goes to members of my department, especially the administrative staff, for their patience and attentive assistance in facilitating various secretarial works. -

CHAPTER 3: OVERVIEW of POLITICAL EVENTS and NATIONAL BUDGET ANNOUNCEMENTS in MALAYSIA the Focus of This Research Study Is On

CHAPTER 3: OVERVIEW OF POLITICAL EVENTS AND NATIONAL BUDGET ANNOUNCEMENTS IN MALAYSIA The focus of this research study is on the impact of political events and national budget announcement on the local stock market. For the purpose of this project, a set of 38 discrete political events with different dates of occurrence which cover a time period of three decades starting from 1981 have been selected. Though a longer perspective is useful in providing a broader view of the picture, this study will not cover events prior to 1981, except for occasional reference and summary during the analysis. The scope of the selected political news is limited to government-oriented announcements which can be broadly categorized into six major types: Dissolutions of the Parliament, General Elections, party elections, the changing of administration leadership, the reshuffle of cabinet and extraordinary political events. This study, however, does not include news from the opposition party. The second part of the research will be dealing with the national budget announcements which broadly include some of the major information such as the country's GDP, balance of payment, fiscal policy, and tax policy. Fifteen years of national budget from 1998 to 2011 have been collected for testing and analysis on their impact on the Malaysian market reactions. 38 3.1 Political events from 1981—1990 The first event of this study dates back to 15 May 1981 when Hussein Onn, the then Prime Minister of Malaysia, first announced his intention to resign due to health problem (Mean, 1991) and would pass the Premiership to Mahathir Mohamad. -

Storm Over Nanyang

PP3739/12/2001 ISSN 0127 - 5127 / RM3.00 / 2001:21(5) STORM OVER NANYANG Aliran Monthly 21(5) Page 1 COVER STORY The Nanyang Takeover Crisis Representing or Opposing Community Interests? by Dr Francis Loh ow that its EGM is over, NN MCA’s takeover of NNN Nanyang Press Hold- ings Bhd is a fait accom- pli. MCA will probably follow the Prime Minister’s advice and shed part of its Nanyang shares to some ‘strategic partners’. The financial burden of assuming 72% of Nanyang shares alone should persuade MCA’s Huaren Hold- ings Sdn Bhd to do this, and sooner rather than later. Only 53 per cent of those who voted at the 24 June EGM favoured the takeover. Even so the ‘Gang of Eight’ led by Lim Ah Lek and Chua Jui Meng have declared that they will accept the EGM’s decision. Their road-shows will stop. The party will close ranks. But for how long? Even if there’s no mud-slinging within MCA, there is still a storm of protest in the Chinese commu- nity against the Nanyang takeo- ver. The protest will not die so quickly but will probably haunt MCA. Indeed Ling Liong Sik’s slim victory suggests MCA is so split that it will only be a matter of Perennial Consider the party feud that has time before another round of in- Succession Feuds festered in recent years between tra-party feuding occurs with MCA president Dr Ling Liong even higher stakes. Then the MCA has had a very fractious Sik and his deputy, Lim Ah Lek. -

Penyata Rasmi Parlimen Parliamentary Debates

Jilid II Hari Selasa Bil. 28 20hb Oktober, 1992 M AL A YSI A PENYATA RASMI PARLIMEN PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DEWAN RAKYAT House of Representatives PARLIMEN KELAPAN Eighth Parliament PENGGAL KEDUA Second Session KANDUNGAN JAWAPAN-JAWAPAN MULUT BAGI PERTANYAAN-PERTANYAAN [Ruangan 6169] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG DIBAWA KE DALAM MESYUARAT [Ruangan 6237] RANG UNDANG-UNDANG: Rang Undang-undang Jualan Langsung 1992 [Ruangan 6238] Rang Undang-undang Perlembagaan (Pindaan) [Ruangan 6263] DICETAK OLEH PERCETAKAN NASIONAL MALAYSIA BERHAD. IBU PEJABAT, KUALA LUMPUR 1994 MALAYSIA DEWAN RAKYAT YANG KELAPAN Penyata Rasmi Parlimen PENGGAL YANG KEDUA AHLI-AHLI DEWAN RAKYAT Yang Berhormat Tuan Yang di-Pertua, TAN SRI DATO MOHAMED ZAHIR BIN HAJI ISMAIL, P.M.N., S.P.M.K., D.S.D.K., J.M.N. Yang Amat Bcrhormat Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Dalam Negeri, DATO' SERI DR MAHATHIR BIN MOHAMAD, D.K.I., D.U.K., S.S.D.K., S.S.A.P., S.P.M.S., S.P.M.J., D.P., D.U.P.N., S.P.N.S., S.P.D.K., S.P.C.M., S.S.M.T., D.U.N.M., P.I.S. (Kubang Pasu). „ Timbalan Perdana Menteri dan Menteri Pembangunan Luar Bandar, TUAN ABDUL GHAFAR BIN BABA (Jasin). Yang Berhormat Menteri Pengangkutan, DATO' SERI DR LING LIONG SIK, S.P.M.P., D.P.M.P., D.P.M.S. (Labis). Menteri Tenaga, Telekom dan Pos, DATO' SERI S. SAMY VELLU, S.P.M.P., S.P.M.J., D.P.M.S., P.C.M., A.M.N. (Sungai Siput). Menteri Perusahaan Utama, DATO' SERI DR LIM KENG YAIK, S.P.M.P., D.P.C.M. -

1994Vol14no.10

I 1 The UMNO Baru General Assembly: ------~------ ~----~------ READING BETWEEN THE LINES Wawasan Team fades, PAS draws flak, Rahim scandal ignored At the UMNO Baru General Assembly held on 18-20 November, the message rang loud and clear - we are one, big, happy family. It was, after all, an assembly where delegates were hypnotised by the dizzying scent of the general election hanging in the air - a time to close ranks and project a sense of greatness. But when the assembly drew to a close and the lights dimmed, questions descended on the carpeted floors of the PWTC and started dancing in rhythmic progression: What had happened to the much-vaunted Wawasan Team? Were delegates gagged on the Rahim issue? Is Mahathir's position secure? How close are Anwar and Daim? Why was PAS singled out for systematic pounding? NNP Is Mahathir's position secure? lifts the carpet in search of clues ... MNO Baru certainly came across as one big, happy and Uunited family at it<; recent General Assembly. This is, after all, not a party election year where political ambitions are too much at stake to think about being united. Hence, it is usually the time for UMNO Baru leaders to sit back and attempt to be profound abput Malay society, its problems and future. We were entertained to endless footage and photographs of the UMNO Baru leadership in a variety of meaningful poses. Dr Mahathir The Assembly: Issues were relevant and important to Malaysian society. Mohamad peering through a pair of binoculars, Wanita leaders looking adoringly at Anwar Ibrahim, generous doses of English literature (never mind, if it was read all wrong), Mahathir and his wife shop ping, Anwar and Daim Zainuddin sharing a cosy chat and so on. -

Chinese Responses to Malay Hegemony in Peninsular Malaysia 1957-96

Southeast Asian Studies. Vol. 34, No.3, December 1996 Chinese Responses to Malay Hegemony in Peninsular Malaysia 1957-96 RENG Pek Koon * Owing to their status as an immigrant minority community, the political, social and economic life of Chinese in Peninsular Malaysia (known as Malaya in the period before 1963) has inevitably been shaped by initiatives emanating from the dominant Malay community. According to the latest census figures released in 1995, Chinese form 29.4% of the population in Peninsular Malaysia compared to 57.4% for Malays and 9.5% for Indians [Government of Malaysia, Department of Statistics Malaysia 1995: VoLl, 40J. This paper examines the impact of Malay hegemony, which emerged with independence in 1957, on Chinese political and economic life. The interplay of Malay ascendance and Chinese responses over the last four decades has undergone three distinct phases: (1) 1957-69 - Alliance coalition rule; (2) 1970-90 National Front (Barisan Nasional) coalition rule and implementation of the New Economic Policy (NEP); (3) 1991-present - implementation of the National Development Policy (NDP). During the first phase, Chinese experienced meaningful political participation and made significant economic gains. The second phase saw concentration of power in the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), a concerted implementation of Malay affirmative action policies, and a concomitant marginalization of Chinese political activity. In the current phase, NDP policies, shaped by the objectives of Prime Minister Mohamad Mahathir's "Vision 2020," have produced a political and economic climate more conducive to Chinese interests. Before turning to a discussion of Chinese political and economic activities in the country, I would like to first consider the manner in which the three core ethnic identifiers of "Malayness" - bahasa, agama, raja (language, religion and royalty) - have been utilized by the Malay political leadership in public policies to reflect Malay hegemonic status in the Malaysian polity.