Scotland and the Novel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rhinehart Collection Rhinehart The

The The Rhinehart Collection Spine width: 0.297 inches Adjust as needed The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university at appalachian state university appalachian state at An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John higby Vol. II boone, north carolina John John h igby The Rhinehart Collection i Bill and Maureen Rhinehart in their library at home. ii The Rhinehart Collection at appalachian state university An Annotated Bibliography Volume II John Higby Carol Grotnes Belk Library Appalachian State University Boone, North Carolina 2011 iii International Standard Book Number: 0-000-00000-0 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 0-00000 Carol Grotnes Belk Library, Appalachian State University, Boone, North Carolina 28608 © 2011 by Appalachian State University. All rights reserved. First Edition published 2011 Designed and typeset by Ed Gaither, Office of Printing and Publications. The text face and ornaments are Adobe Caslon, a revival by designer Carol Twombly of typefaces created by English printer William Caslon in the 18th century. The decorative initials are Zallman Caps. The paper is Carnival Smooth from Smart Papers. It is of archival quality, acid-free and pH neutral. printed in the united states of america iv Foreword he books annotated in this catalogue might be regarded as forming an entity called Rhinehart II, a further gift of material embodying British T history, literature, and culture that the Rhineharts have chosen to add to the collection already sheltered in Belk Library. The books of present concern, diverse in their -

Eg Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Digging up the Kirkyard: Death, Readership and Nation in the Writings of the Blackwood’s Group 1817-1839. Sarah Sharp PhD in English Literature The University of Edinburgh 2015 2 I certify that this thesis has been composed by me, that the work is entirely my own, and that the work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified. Sarah Sharp 3 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Penny Fielding for her continued support and encouragement throughout this project. I am also grateful for the advice of my secondary supervisor Bob Irvine. I would like to acknowledge the generous support of the Wolfson Foundation for this project. Special thanks are due to my parents, Andrew and Kirsty Sharp, and to my primary sanity–checkers Mohamad Jahanfar and Phoebe Linton. -

Lockhart'smemoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 38 | Issue 1 Article 16 2012 WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART'S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART. Gerald P. Mulderig DePaul University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mulderig, Gerald P. (2012) "WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART'S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART.," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 38: Iss. 1, 119–138. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol38/iss1/16 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WRITER, READER, AND RHETORIC IN JOHN GIBSON LOCKHART’S MEMOIRS OF THE LIFE OF SIR WALTER SCOTT, BART. Gerald P. Mulderig “[W]hat can the best character in any novel ever be, compared to a full- length of the reality of genius?” asked John Gibson Lockhart in his 1831 review of John Wilson Croker’s edition of Boswell’s Life of Johnson.1 Like many of his contemporaries in the early decades of the nineteenth century, Lockhart regarded Boswell’s dramatic recreation of domestic scenes as an intrusive and doubtfully appropriate advance in biographical method, but also like his contemporaries, he could not resist a biography that opened a window on what he described with Wordsworthian ardor as “that rare order of beings, the rarest, the most influential of all, whose mere genius entitles and enables them to act as great independent controlling powers upon the general tone of thought and feeling of their kind” (ibid.). -

Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott's Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I Conscious of Any Thing Peculiar in My Own Moral

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Mary's University Open Research Archive Disfigurement and Disability: Walter Scott’s Bodies Fiona Robertson Were I conscious of any thing peculiar in my own moral character which could render such development [a moral lesson] necessary or useful, I would as readily consent to it as I would bequeath my body to dissection if the operation could tend to point out the nature and the means of curing any peculiar malady.1 This essay considers conflicts of corporeality in Walter Scott’s works, critical reception, and cultural status, drawing on recent scholarship on the physical in the Romantic Period and on considerations of disability in modern and contemporary poetics. Although Scott scholarship has said little about the significance of disability as something reconfigured – or ‘disfigured’ – in his writings, there is an increasing interest in the importance of the body in Scott’s work. This essay offers new directions in interpretation and scholarship by opening up several distinct, though interrelated, aspects of the corporeal in Scott. It seeks to demonstrate how many areas of Scott’s writing – in poetry and prose, and in autobiography – and of Scott’s critical and cultural standing, from Lockhart’s biography to the custodianship of his library at Abbotsford, bear testimony to a legacy of disfigurement and substitution. In the ‘Memoirs’ he began at Ashestiel in April 1808, Scott described himself as having been, in late adolescence, ‘rather disfigured than disabled’ by his lameness.2 Begun at his rented house near Galashiels when he was 36, in the year in which he published his recursive poem Marmion and extended his already considerable fame as a poet, the Ashestiel ‘Memoirs’ were continued in 1810-11 (that is, still before the move to Abbotsford), were revised and augmented in 1826, and ten years later were made public as the first chapter of John Gibson Lockhart’s Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, Bart. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

The Effect of School Closure On

The Business of Writing Home: Authorship and the Transatlantic Economies of John Galt’s Literary Circle, 1807-1840 by Jennifer Anne Scott M.A. (English), Simon Fraser University, 2006 B.A. (Hons.), University of Winnipeg, 2005 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Jennifer Anne Scott 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2013 Approval Name: Jennifer Anne Scott Degree: Doctor of Philosophy (English) Title of Thesis: The Business of Writing Home: Authorship and the Transatlantic Economies of John Galt’s Literary Circle, 1807-1840. Examining Committee: Chair: Jeff Derksen Associate Professor Leith Davis Senior Supervisor Professor Carole Gerson Senior Supervisor Professor Michael Everton Supervisor Associate Professor Willeen Keough Internal Examiner Associate Professor Department of History Kenneth McNeil External Examiner Professor Department of English Eastern Connecticut State University Date Defended/Approved: May 16, 2013 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract This dissertation examines nineteenth-century Scottish author John Galt’s dialogue with the political economics of his time. In particular, I argue that both in his practices as an author and through the subject matter of his North American texts, Galt critiques and adapts Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations (1776). Galt’s critique of Smith becomes evident when we examine the relationship between his engagement with political economy in his most important North American literary texts and his overt political interests, specifically those concerning transatlantic land development and colonial expansion, a project he pursued with the Canada Company. In Chapter One, I examine John Galt’s role with the Canada Company. -

Hogg, Byron, Scott, and John Murray of Albemarle Street Douglas S

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 23 2007 Hogg, Byron, Scott, and John Murray of Albemarle Street Douglas S. Mack University of Stirling, Emeritus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mack, Douglas S. (2007) "Hogg, Byron, Scott, and John Murray of Albemarle Street," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 307–325. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/23 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Douglas S. Mack Hogg, Byron, Scott, and John Murray of Albemarle Street For a' that, and a' that, Its comin yet for a' that, That Man to Man the warld o'er, Shall brothers be for a' that. Robert Burns Towards the end of January 1813 the young Edinburgh publisher George Goldie brought out a new book-length poem, The Queen's Wake. Somewhat unpromisingly, the book was by a little-known and impecunious former shep herd called James Hogg, whose recent attempts to launch a career, first as a farmer and later as a journalist, had ended in failure. Unexpectedly, the poem was very well received by reviewers and by the reading public, and by the au tumn of 1814 both fame and fortune appeared to be within the grasp of the author of The Queen's Wake. -

The Argosy – Bmds ‐ 1891

The Argosy – BMDs ‐ 1891 SATURDAY JANUARY 3 1891 P 4 COL Birth RITCHIE ‐ At St Andrew's Manse, Georgetown, on January 2nd, the wife of the Rev. W.B. Ritchie, of a Daughter. Married TAYLOR‐DOUGALL ‐ At Ebenezer Church, West Coast, Demerara, on 27th December, 1890, by the Rev. James Millar, Minister of the parish, assisted by the Rev. J.L. Green, Henry John Taylor, eldest son of Major William Taylor, R.A., Renfrewshire, N.B., to Anna Rebecca Stuart., eldest daughter of David Dougall, of Pln. Blankenburg. Died CHOPPIN ‐ On 27th December, 1890, at Blankenburg, West Coast, Demerara, Gerald Crosby, aged 28 years, 3rd Class Clerk in the Government Land's Dept. SPEIRS ‐ At the Manse, New Amsterdam, on the 31st ult., Susan Walker, wife of the Rev. James Speirs. SATURDAY JANUARY 10 1891 P 4 COL 1 Birth GETTING ‐ On December 30th, 1890, at Kaieteur College Rd., Norwood, London, the wife of Henry F. Getting, of a Son. Died DE PRADEL ‐ At Paris, on the 16th December, 1890, of Diphtheria, George Eugene, son of Dr. and Mme. De Pradel, aged 2 years and 9 months. FRANCIS ‐ On the morning of the 8th instant, at Lot 189, Upper Charlotte Street, Alfred Cyril, infant son of Charles and Winnie Francis. Aged 9 weeks. SATURDAY JANUARY 17 1891 P 4 COL 1 Married CHAPMAN‐FARLEY ‐ On the 13th instant, at Vryheid's Lust Church, by the Rev. Thomas Slater, Joseph Ivelaw Chapman, to Shirley Isabel, youngest daughter of the late W.H.N.Farley. SATURDAY JANUARY 24 1891 P 4 COL 1 Birth IRVING ‐ At New Amsterdam, on the 20th instant, the wife of M.H.C. -

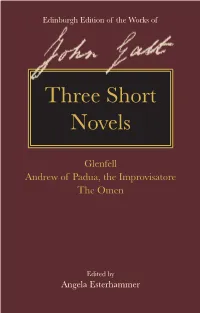

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

Landscaping Justice, Rebellion and Dynastic Failure in the Heart of Mid-Lothian, Waverley and Redgauntlet

Chapter 4 Landscaping Justice, Rebellion and Dynastic Failure in The Heart of Mid-Lothian, Waverley and Redgauntlet Our environment, conceived as landscape scenery, is fundamentally linked to our political landscape. kenneth r. olwig1 ⸪ There is no shortage of critical appraisal focused on Scott’s use of landscape to explore his thematic concerns in the Waverley Novels.2 As Jenni Calder points out, much of Scott’s popularity was the direct result of “his conjuring of a myth- ic history out of mountains, lochs and ruins”.3 Of course, Scott uses Highland 1 Kenneth R. Olwig, Landscape, Nature, and the Body Politic: From Britain’s Renaissance to America’s New World (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002), xxxii. 2 See, for example, James Buzard’s Disorienting Fiction: The Autoethnographic Work of Nine- teenth-Century British Novels (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005); Penny Fielding’s ‘Curated Regions of the North: Art and Literature in the “Scottish Border” and the “Transpen- nine Corridor,”’ Visual Culture in Britain, 15 (2014), 159–72, and Scotland and the Fictions of Geography: North Britain, 1760–1830 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008); and Yoon Sun Lee’s chapter on Scott in Nationalism and Irony: Burke, Scott, Carlyle (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 74–104. See also the following recent commentary on Scott and his use of landscape: Chris Ewers. ‘Roads as Regions, Networks and Flows: Waverley and the “Periphery” of Romance,’ Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, 37 (2014), 97–112; E. García Díaz. ‘An Overview of Justice in Sir Walter Scott’s Waverley Novels: The Heart of Mid-Lothian.’ Oñati Socio-legal Series [online], 4 (2014), 1167–72; Anna Faktorovich. -

1 Mathew and Henry Carey, Archibald Constable, and the Discourse

1 Mathew and Henry Carey, Archibald Constable, and the Discourse of Materiality in the Anglophone Periphery Joseph Rezek, Boston University A Paper Submitted to “Ireland, America, and the Worlds of Mathew Carey” Co-Sponsored by: The McNeil Center for Early American Studies The Program in Early American Economy and Society The Library Company of Philadelphia, The University of Pennsylvania Libraries Philadelphia, PA October 27-29, 2011 *Please do not cite without permission of the author 2 British and American literary publishing were not separate affairs in the early nineteenth century. The transnational circulation of texts, fueled by readerly demand on both sides of the Atlantic; a reprint trade unregulated by copyright law and active, also, on both sides of the Atlantic; and transatlantic publishing agreements at the highest level of literary production all suggest that, despite obvious national differences in culture and circumstance, authors and booksellers in Britain and the United States participated in a single literary field. This literary field cohered through linked publishing practices and a shared English-language literary heritage, although it was also marked by internal division and cultural inequalities. Recent scholarship in the history of books, reading, and the dissemination of texts has suggested that literary producers in Ireland, Scotland, and the United States occupied analogous positions as they nursed long- standing rivalries with England and depended on English publishers and readers for cultural legitimation. Nowhere is such rivalry and dependence more evident than in the career of the most popular author in the period, Walter Scott, whose books were printed in Edinburgh but distributed mostly in London, where they reached their largest and most lucrative audience. -

Waverley (Novel) - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Waverley (novel) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waverley_(novel) From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Waverley is an 1814 historical novel by Sir Walter Scott. Initially Waverley published anonymously in 1814 as Scott's first venture into prose fiction, Waverley is often regarded as the first historical novel. It became so popular that Scott's later novels were advertised as being "by the author of Waverley". His series of works on similar themes written during the same period have become collectively known as the "Waverley Novels". In 1815, Scott was given the honour of dining with George, Prince Regent, who wanted to meet "the author of Waverley". It is thought that at this meeting Scott persuaded George that as a Stuart prince he could claim to be a Jacobite Highland Chieftain, a claim that would be dramatised when George became King and visited Scotland.[1] Illustration to 1893 edition, by J. Pettie. Waverley Abbey is noted by English Heritage to be Sir Walter Scott's inspiration for this novel.[2] However, this was probably Author Sir Walter Scott not the case.[3] Country United Kingdom Language English, Lowland Scots, some Scottish Gaelic and French Series Waverley Novels 1 Plot introduction 2 Plot summary Genre(s) Historical novel 3 Characters Publisher Archibald Constable 4 Major themes 5 Allusions/references to other works Publication date 1814 6 Literary significance & criticism Followed by Guy Mannering 7 Allusions/references from other works 8 Allusions/references to actual history, geography and current science 9 Miscellany 10 See also 11 References 12 External links Waverley is set during the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745, which sought to restore the Stuart dynasty in the person of Charles Edward Stuart (or 'Bonnie Prince Charlie').