The Effect of School Closure On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Your Guide to Huron County Hiking

Your Guide to Huron County Hiking HikingGuide www.ontarioswestcoast.caPage 1 Huron County’s Hiking Experience Welcome to Huron County . Ontario’s West Coast! Discover the enjoyment of the outdoors for pleasure and improved health through walking, cycling and cross country skiing. Located in Southwestern Ontario, Huron County offers trail enthusiasts of all ages and skill levels a variety of terrains from natural paths to partially paved routes. Come and explore! Huron County is a vacation destination of charm, culture, beauty and endless possibilities! Contact the address or number below and ask for your free copy of the Ontario’s West Coast Vacation Guide to help plan your hiking adventure! For the outdoor recreation enthusiast, Huron County also offers a free Cycling Guide and a Fish/Paddle brochure. For information about these and additional conservation areas and heritage walking tours, contact us. GEORGIAN BAY Owen Sound LAKE SIMCOE LAKE HURON Barrie Kincardine HURON COUNTY Wingham Goderich Blyth Brussels Toronto Clinton Bayfield Seaforth Kitchener/ Zurich Hensall Waterloo Guelph LAKE Exeter Stratford Grand Bend ONTARIO MICHIGAN Niagara Falls, Hamilton USA Trail User’s Code Niagara Falls Port Huron London Sarnia LAKE ST. CLAIR Detroit Windsor LAKE ERIE Kilometers 015 0203040 For your complete Huron County travel information package contact: [email protected] or call 1-888-524-8394 EXT. 3 County of Huron, 57 Napier St., Goderich, Ontario • N7A 1W2 Publication supported by the County of Huron Page 2 Printed in Canada • Spring 2016 (Sixth Edition) How To Use This Guide This Guide Book is designed as a quick and easy guide to hiking trails in Huron County. -

Curriculum Vitae

1 Academic Curriculum Vitae Dr. Sharon-Ruth Alker Current Position 2020 to date Chair of Division II: Humanities and Arts 2018 to date Mary A. Denny Professor of English and General Studies 2017 to date Professor of English and General Studies 2017 to 2019 Chair of the English Department, Whitman College 2010 to 2017 Associate Professor of English and General Studies Whitman College 2004 to 2010 Assistant Professor of English and General Studies Whitman College, Walla Walla, WA. Education *University of Toronto – 2003-2004 Postdoctoral Fellowship * University of British Columbia - 1998 to 2003 - PhD. English, awarded 2003 Gendering the Nation: Anglo-Scottish relations in British Letters 1707-1830 * Simon Fraser University - 1998 MA English * Simon Fraser University - 1996 BA English and Humanities Awards 2020 Aid to Scholarly Publications Award, Federation for Humanities and Social Sciences (Canadian). This is a peer-reviewed grant. For Besieged: The Post War Siege Trope, 1660-1730. 2019 Whitman Perry Grant to work with student Alasdair Padman on a John Galt edition. 2018 Whitman Abshire Grant to work with student Nick Maahs on a James Hogg 2 website 2017 Whitman Perry Grant to work with student Esther Ra on James Hogg’s Uncollected Works and an edition of John Galt’s Sir Andrew Wylie of that Ilk 2017 Whitman Abshire Grant to work with student Esther Ra on James Hogg’s Manuscripts 2016 Co-organized a conference that received a SSHRC Connection Grant to organize the Second World Congress of Scottish Literatures. Conference was in June 2017. 2015 Whitman Perry Grant to work with student Nicole Hodgkinson on chapters of the military siege monograph. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

POP Again, Janet Jackson a Hard Day's Night, The

POP Again, Janet Jackson A Hard Day’s Night, The Beatles All I Want Is You, U2 All Of Me, John Legend All The Small Things, Blick 182 All You Need Is Love, The Beatles Amazed, Lonestar And I Love Her, The Beatles And So It Goes, Billy Joel Angels, Robbie Williams Annie’s Song, John Denver Autumn Leaves, Eva Cassidy Back In The USSR, The Beatles Beautiful Day, U2 Because You Loved Me, Celine Dion Better Together, Jack Johnson Billie Jean, Michael Jackson Bittersweet SymPhony, The Verve Blackbird, The Beatles Bless The Broken Road, Rascal Flatts Blue Sky, The Allman Brothers Blueberry Hill, Fats Domino Bohemian RhaPsody, Queen Can’t Buy Me Love, The Beatles Can’t HelP Falling In Love, Elvis Careless WhisPer, Wham! Celebration, Kool & The Gang Chasing Cars, Snow Patrol Clocks, Coldplay Color My World, Chicago Come Away With Me, Norah Jones Counting Stars, One Republic Crazy For You, Madonna Crazy Little Thing Called Love, Queen Dancing Queen, ABBA Danny’s Song, Anne Murray Day Tripper, The Beatles Don’t Stop Believin’, Journey Don’t You…Forget About Me, Simple Minds Eight Days A Week, The Beatles Eleanor Rigby, The Beatles Endless Love, Lionel Ritchie Every Breath You Take, Sting Every Teardrop Is A Waterfall, Coldplay Everything I Do, Bryan Adams Feel So Close, Calvin Harris Fields Of Gold, Sting Firework, Katy Perry From A Distance, Bette Midler The Fool On The Hill, The Beatles Get Back, The Beatles Get Lucky, Daft Punk Girl On Fire, Alicia Keys Good Day Sunshine, The Beatles Got To Get You Into My Life, The Beatles A Groovy Kind Of Love, -

Death Cab for Cutie Ðлбуð¼

Death Cab for Cutie ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) Plans https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/plans-16419/songs Transatlanticism https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/transatlanticism-16418/songs Narrow Stairs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/narrow-stairs-16420/songs Something About Airplanes https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/something-about-airplanes-16415/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/we-have-the-facts-and-we%27re-voting- We Have the Facts and We're Voting Yes yes-16416/songs The Photo Album https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-photo-album-16417/songs Codes and Keys https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/codes-and-keys-16421/songs The Forbidden Love EP https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-forbidden-love-ep-7734738/songs Kintsugi https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/kintsugi-18786450/songs Thank You for Today https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/thank-you-for-today-55080329/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/itunes-originals-%E2%80%93-death-cab- iTunes Originals – Death Cab for Cutie for-cutie-3146983/songs The John Byrd EP https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-john-byrd-ep-7743362/songs Studio X Sessions EP https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/studio-x-sessions-ep-7628265/songs Drive Well, Sleep Carefully – On the https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/drive-well%2C-sleep-carefully- Road with Death Cab for Cutie %E2%80%93-on-the-road-with-death-cab-for-cutie-5307925/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/directions%3A-the-plans-video-album- Directions: The Plans Video Album 5280453/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/you-can-play-these-songs-with-chords- You Can Play These Songs with Chords 2517302/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/you-can-play-these-songs-with-chords- You Can Play These Songs with Chords 2499825/songs. -

The Argosy – Bmds ‐ 1891

The Argosy – BMDs ‐ 1891 SATURDAY JANUARY 3 1891 P 4 COL Birth RITCHIE ‐ At St Andrew's Manse, Georgetown, on January 2nd, the wife of the Rev. W.B. Ritchie, of a Daughter. Married TAYLOR‐DOUGALL ‐ At Ebenezer Church, West Coast, Demerara, on 27th December, 1890, by the Rev. James Millar, Minister of the parish, assisted by the Rev. J.L. Green, Henry John Taylor, eldest son of Major William Taylor, R.A., Renfrewshire, N.B., to Anna Rebecca Stuart., eldest daughter of David Dougall, of Pln. Blankenburg. Died CHOPPIN ‐ On 27th December, 1890, at Blankenburg, West Coast, Demerara, Gerald Crosby, aged 28 years, 3rd Class Clerk in the Government Land's Dept. SPEIRS ‐ At the Manse, New Amsterdam, on the 31st ult., Susan Walker, wife of the Rev. James Speirs. SATURDAY JANUARY 10 1891 P 4 COL 1 Birth GETTING ‐ On December 30th, 1890, at Kaieteur College Rd., Norwood, London, the wife of Henry F. Getting, of a Son. Died DE PRADEL ‐ At Paris, on the 16th December, 1890, of Diphtheria, George Eugene, son of Dr. and Mme. De Pradel, aged 2 years and 9 months. FRANCIS ‐ On the morning of the 8th instant, at Lot 189, Upper Charlotte Street, Alfred Cyril, infant son of Charles and Winnie Francis. Aged 9 weeks. SATURDAY JANUARY 17 1891 P 4 COL 1 Married CHAPMAN‐FARLEY ‐ On the 13th instant, at Vryheid's Lust Church, by the Rev. Thomas Slater, Joseph Ivelaw Chapman, to Shirley Isabel, youngest daughter of the late W.H.N.Farley. SATURDAY JANUARY 24 1891 P 4 COL 1 Birth IRVING ‐ At New Amsterdam, on the 20th instant, the wife of M.H.C. -

Three-Deckers and Installment Novels: the Effect of Publishing Format Upon the Nineteenth- Century Novel

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1965 Three-Deckers and Installment Novels: the Effect of Publishing Format Upon the Nineteenth- Century Novel. James M. Keech Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Keech, James M. Jr, "Three-Deckers and Installment Novels: the Effect of Publishing Format Upon the Nineteenth-Century Novel." (1965). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1081. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1081 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been - microfilmed exactly as received 66-737 K E E C H , Jr., James M., 1933- THREE-DECKERS AND INSTALLMENT NOVELS: THE EFFECT OF PUBLISHING FORMAT UPON THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY NOVEL. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1965 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THREE-DECKERS AMD INSTALLMENT NOVELS: THE EFFECT OF PUBLISHING FORMAT UPON THE NINETEENTH-CENTURY NOVEL A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulflllnent of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English hr James M. Keech, Jr. B.A., University of North Carolina, 1955 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1961 August, 1965 ACKNOWLEDGMENT I wish to express my deepest appreciation to the director of this study, Doctor John Hazard Wildman. -

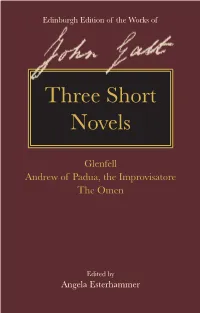

Three Short Novels Their Easily Readable Scope and Their Vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, Themes, Each of the Stories Has a Distinct Charm

Angela Esterhammer The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt Edited by John Galt General Editor: Angela Esterhammer The three novels collected in this volume reveal the diversity of Galt’s creative abilities. Glenfell (1820) is his first publication in the style John Galt (1779–1839) was among the most of Scottish fiction for which he would become popular and prolific Scottish writers of the best known; Andrew of Padua, the Improvisatore nineteenth century. He wrote in a panoply of (1820) is a unique synthesis of his experiences forms and genres about a great variety of topics with theatre, educational writing, and travel; and settings, drawing on his experiences of The Omen (1825) is a haunting gothic tale. With Edinburgh Edition ofEdinburgh of Galt the Works John living, working, and travelling in Scotland and Three Short Novels their easily readable scope and their vivid England, in Europe and the Mediterranean, themes, each of the stories has a distinct charm. and in North America. While he is best known Three Short They cast light on significant phases of Galt’s for his humorous tales and serious sagas about career as a writer and show his versatility in Scottish life, his fiction spans many other genres experimenting with themes, genres, and styles. including historical novels, gothic tales, political satire, travel narratives, and short stories. Novels This volume reproduces Galt’s original editions, making these virtually unknown works available The Edinburgh Edition of the Works of John Galt is to modern readers while setting them into the first-ever scholarly edition of Galt’s fiction; the context in which they were first published it presents a wide range of Galt’s works, some and read. -

Death Cab for Cutie

ISSUE #41 MMUSICMAG.COM ISSUE #41 MMUSICMAG.COM Q&A Did that affect the album? Were you happy with the results? How did you fi nd Dave Depper? I don’t think so. It wasn’t like there was This being our fi rst record with an outside Dave has been a friend of ours for a long any bad blood, but we didn’t tell Rich that producer, it’s kind of a transitional record. I time, and he’s been a noted northwest Chris was leaving the band until after the really enjoyed working with Rich throughout. musical fi gure for a long time. When we were record was done—just because we didn’t He did a phenomenal job with the album— thinking of who we were going to play with, want exactly what you’re talking about to fi tting some of the newer demos, the way I’d he was literally the fi rst person we thought happen. It was better for the record and written the songs, with the stuff we’d already of. It was that kind of thing where we didn’t better for everybody. But it wasn’t a dramatic recorded with Chris in the summer of 2013. waste a lot of time thinking, “Oh, my God, or loaded-gun experience—it was more like, When we had the fi nal versions we knew what will we do?” We just thought, “OK, who “OK, let’s do the work.” In some ways, it Rich had been the right man for the job and shall we get in?” Dave was the fi rst person was like Chris was a very familiar session he brought the best out of us and the songs. -

Death Cab for Cutie Transatlanticism Full Album Download >>> DOWNLOAD

Death Cab For Cutie Transatlanticism Full Album Download >>> DOWNLOAD 1 / 3 Death Cab For Cutie - Transatlanticism (Full Album - Seamlessly Looped) Download, Listen and View free Death Cab For Cutie - Transatlanticism (Full Album .Death Cab For Cutie Transatlanticism Mp3 is popular Free Mp3. You can download or play Death Cab For Cutie Transatlanticism Mp3 with best mp3 quality online streaming .Buy Death Cab For Cutie Transatlanticism Mp3 Download. Preview full album. 00:00; Track title Duration . Discography of Death Cab For Cutie.Free download Transatlanticism mp3 for free . Death Cab For Cutie - Transatlanticism (Full Album . Play Download. Death Cab for Cutie - Transatlanticism (Full .Download free for Death Cab For Cutie Transatlanticism Full Album Seamlessly Looped or search any related Death Cab For Cutie Transatlanticism Full Album Seamlessly .Listen to songs from the album Transatlanticism, . Death Cab for Cutie's rise from small- time solo project . while a third full-length effort, The Photo Album, .Death Cab For Cutie - Transatlanticism (Full Album - Seamlessly Looped).mp3Death Cab For Cutie Transatlanticism Full Album Seamlessly Looped mp3 download free by Mp3Clem.com, 11.16MB Enjoy listening Death Cab For Cutie Transatlanticism .Free Download Death Cab For Cutie Transatlanticism Full Album Seamlessly Looped MP3, Size: 240.03 MB, Duration: 3 hours, 2 minutes and 23 seconds, Bitrate: 192 Kbps.Transatlanticism (10th Anniversary Edition) . things have gotten as crazy as it gets for Death Cab for Cutie since 2002's . MP3 download When you buy an album .Transatlanticism Death Cab For Cutie mp3 Download. Death Cab For Cutie Transatlanticism mp3. Death Cab For Cutie Transatlanticism Full Album Seamlessly Looped mp3.Free death cutie transatlanticism mp3 music download, easily listen and download death cutie transatlanticism mp3 files on Mp3Juices.Transatlanticism by Death Cab for Cutie, . -

The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: a History of Corporate Ownership in Canada

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: A History of Corporate Governance around the World: Family Business Groups to Professional Managers Volume Author/Editor: Randall K. Morck, editor Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-53680-7 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/morc05-1 Conference Date: June 21-22, 2003 Publication Date: November 2005 Title: The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm: A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Author: Randall Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Tian, Bernard Yeung URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c10268 1 The Rise and Fall of the Widely Held Firm A History of Corporate Ownership in Canada Randall K. Morck, Michael Percy, Gloria Y. Tian, and Bernard Yeung 1.1 Introduction At the beginning of the twentieth century, large pyramidal corporate groups, controlled by wealthy families or individuals, dominated Canada’s large corporate sector, as in modern continental European countries. Over several decades, a large stock market, high taxes on inherited income, a sound institutional environment, and capital account openness accompa- nied the rise of widely held firms. At mid-century, the Canadian large cor- porate sector was primarily freestanding widely held firms, as in the mod- ern large corporate sectors of the United States and United Kingdom. Then, in the last third of the century, a series of institutional changes took place. These included a more bank-based financial system, a sharp abate- Randall K. Morck is Stephen A. Jarislowsky Distinguished Professor of Finance at the University of Alberta School of Business and a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research. -

(Death Cab for Cutie) Y Venir a Tocar a España” Ser Mi Tercera Vez Allí Y Siempre Lo Pasé Muy Bien

Vais a tocar en el FIB. ¿Qué opináis de los grandes “Es duro festivales? Hay buenos y malos festivales, todo depende del lugar donde se hagan. Por ejemplo, no lo pasé nada bien en ser vegetariano Coachella (uno de los más famosos de EE UU), estaba Chris Walla muy mal organizado. Benicàssim es distinto. Esta va a (Death Cab for Cutie) y venir a tocar a España” ser mi tercera vez allí y siempre lo pasé muy bien. Después de alcanzar el éxito planetario con Plans, ¿Qué os parece España? Death Cab for Cutie publican Narrow Stairs. Me encanta España. En una de las primeras giras hicimos Un sexto álbum en el que vuelven a hacer lo que catorce fechas, lo que es increíble. Lo único que llevo mejor se les da: indie rock de delicadas melodías, mal de España es que soy vegetariano. Es muy duro serlo dulce y crudo a la vez, emocional e imprevisible. e ir a tocar allí, particularmente en Madrid. Hay carne por todas partes (risas). Es la única pega que tiene. Chris Walla es, además del guitarrista, productor Muchos esperan saber algo de The Postal Service (el y artífice del sonido de una banda que se ha proyecto paralelo de Gibbard con Jimmy Tamborello). hecho más grande de lo que nunca imaginaron. Me imagino que habría que preguntarle a Ben… Trabajar contigo como productor otorga a la banda Esta vez habéis escogido un single de más de 8 minutos. una perspectiva que no todos los grupos tienen… Es algo arriesgado e inusual… Sí, pero te puedo decir que no hay nada de nada.