Prisoners of Freedom. a Study On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

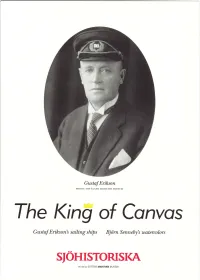

The Ki Ng of Conyos

The Ki ng of Conyos Gustaf Erikson's sai,ling shi,ps Bjtirn Senneby's watercolors sIoHrsToRrsKA en del av STATENS MARITIMA MUSEER ri#{ffi' r+f,**&:;]!$@$j! jr:+{ff 1*.; ff. Pamir Watercolor fu Bji;rn Senneby. GUSTAF ERIKSON The ship's owner, Gustaf Erikson, was born on Europe. The shipping company w:ls at its largest z4 October, r87z in Lemland, in southern Åland. in rg35, when Gustav was 58 years old. At the Both his father and grandfather had worked at time, the company had z9 vessels r5 of which sea. Gustafsson started his life at sea as a tG'year- were large sailing ships without alternative means old, when he served as a cabin boy on the bark of propulsion. GustafAdolf Mauritz Erikson died Neptun over the summer. When he reached r3, on August Lbn, rg47 in Mariehamn. he worked as a cook on the same vessel. He Gustaf Erikson was also part owner of advanced through the ranks and in r89r, at rg several steamers and motor vessels, but it was as years old, was the master's assistant on the barque the owner of the great sailing ships that he was Southern Bellc.In rgoo he took his captain's exlm best known. Four of his large sailing vessels, all and betr,veen 19o6 and r9r3 he was an executive four-masted steel barques, are preserved to this officer on different oceangoing voyages. day: Moshulu,whichwon the lastgrain race tggg, Over the years he had bought shares in is now a restaurant in Philadelphia, USA. -

Training and Certification; and Fishing and Marine Motorman Qualifications

STAATSKOERANT, 6 FEBRUARIE 2012 No.35004 3 GOVERNMENT NOTICE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORT No. R. 83 6 February 2012 Merchant Shipping Act, 1951 (Act No. 57 of 1951) Publication for comments of the Merchant Shipping (Training and Certification) (Fishing and Marine Motorman Qualifications) Regulations, 2012 Submission should be posted to the Director - General Department of The above- mentioned draft Regulations in the Schedule are hereby published for public comments. Interested persons are invited to submit written comments on the draft Regulations within 30 days from the date of publication In the Gazette. Transport for the attention of Mr. Trevor Mphahlele or Adv. A. Masombuka E- MAIL: [email protected] Tel :( 012) 309 3481 Fax :( 012) 309 3134 The Department of Transport Private Bag x193 PRETORIA 0001 E- MAIL: [email protected] Tel :( 012) 309 3888 Fax:( 012) 309 3134 The Department of Transport Private Bag x193 PRETORIA 0001 4 No.35004 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 6 FEBRUARY 2012 Schedule Arrangement of regulations Part 1 Preliminary Title and commencement 2 Definitions 3 Introduction to certification 4 Equivalent certification Part2 Administration 5 Registrar of seafarers 6 Senior examiners 7 Quality assurance 8 Syllabus committee 9 Accreditations and approvals Part3 Certification Division 1 General 10 Dates and places for level 3 assessments 11 How to apply 12 Examiner may verify eligibility 13 Proficiency in English 14 Unsatisfactory conduct 15 Bribery 16 Assessing competence 17 Level 2 assessment STAATSKOERANT, 6 FEBRUARIE 2012 No.35004 -

Maritime Careers Faculty of Nautical Studies CONTENTS Why Choose City of Maritime Industry

Maritime Careers Faculty of Nautical Studies CONTENTS Why Choose City of Maritime Industry .................................................................................................................................04 Roles & Duties On Board A Ship .....................................................................................................06 Glasgow College? Point to Consider (Advantages & Disadvantages of a Merchant Navy Career) ..................................08 • Delivering high quality nautical training Is This Career For Me? ..........................................................................................................................10 since 1969 Academic Routes & Entry Requirements ....................................................................................12 • One of Scotland’s biggest colleges, home to almost 30,000 students and 1,200 staff Other Entry Requirements ..................................................................................................................14 • 360 Deck and Engine cadets enrolled each ....................................................................................................................................16 Career Prospects year from UK and international companies Application Process ..............................................................................................................................18 • Modern, world-class campuses in the centre Contacts .....................................................................................................................................................19 -

Sea Centurion

Report on the investigation of the fatal accident to a motorman on board thero-ro cargo ship Sea Centurion at the Portsmouth Naval Base on 18 May 1999 Marine Accident Investigation Branch First Floor Carlton House Carlton Place S outhampton SO15 2DZ Extract from The Merchant Shipping (Accident Reporting and Investigation) Regulations 1999 The fundamental purpose of investigating an accident under these Regulations is to determine its circumstances and the causes with the aim of improving the safety of life at sea and the avoidance of accidents in the future. It is not the purpose to apportion liability, nor, except so far as is necessary to achieve the fundamental purpose, to apportion blame. CONTENTS Page GLOSSARY SYNOPSIS 1 SECTION 1 - FACTUAL INFORMATION 2 1.1 Particulars of' ship and accident 2 1 1 1 Details of Sea Centurion 2 1 1 2 Details of the accident 2 1.2 Narrative 3 12 1 Background 3 1 2 2 The accident 3 1.3 Environmental conditions 6 1.4 Sea Centurion 6 1 4 1 Brief description 6 1 4 2 The ship's complement 7 1 4 3 Working practices 8 1.5 Powerful 9 1 5 1 Briefdescription 9 1 5 2 The master and relief master 9 1.6 Relevant sections from the Code of Safe Working Practices 10 for Merchant Seamen 1.7 Occupational health and safety 11 SECTION 2 - ANALYSIS 13 2.1 Aim 13 2.2 Allocation of tasks 13 2.3 The snagging of the mooring rope 13 2.4 The accident to the motorman 15 SECTION 3 - CONCLUSIONS 17 3.1 Findings 17 3.2 Cause 19 3.3 Contributory causes 19 SECTION 4 - RECOMMENDATIONS 21 ANNEXE Voith Schneider propulsion units GLOSSARY -

Surface Transportation Board, DOT § 1245.6

Surface Transportation Board, DOT § 1245.6 § 1245.6 Cross reference to standard Job title SOC occupational classification manual. Chief Medical Officer ....................... 261. Job title SOC Medical Officer ................................ 261. Surgeon ........................................... 261. 100 Executives, Officials and Staff As- Company Surgeon .......................... 261. sistants Engineer .......................................... 1639. 101 Executive and General Officers: Architect .......................................... 161. President ......................................... 121. Chief Chemist .................................. 1845. Vice President ................................. 121. Nurse ............................................... 29 and 366. Assist. Vice President ..................... 121. Tax Accountant ............................... 1412. Controller ......................................... 122. Internal Auditor to Gen. Accountant 1412. Treasurer ......................................... 122. Corporate Accountant ..................... 1412. Director (Head of Sub-Department) 139. Supervisor Programming ................ 137. General Superintendent .................. 139. Senior Computer System ................ 1712. Subdepartment Head ...................... 139. Specialist Senior System Analyst ... 1712. Chief Engineer ................................ 1342 and 1639. 202 Subprofessionals: General Manager (Dept. or Sub- 137. Draftsman ........................................ 372. department Head). Chemist -

Investigating Seafarers' Hard and Soft Skills in Maritime

Investigating seafarers’ hard and soft skills in maritime logistics: an overarching approach Teresina Torre*, Marta Giannoni**, Giovanni Colzi*** Summary: 1. Introduction – 2. Hard and soft skills: theoretical background – 3. Empirical research - 3.1 Presentation – 3.2 Method and data – 4. Hard Skills – 4.1 Hard skills quantitative assessment- 4.2 Meso-level hard skills - 4.3 Hard Skills as “testers” for on-shore requalification - 5. Soft skills – 6. Theoretical model – 7. Implications and future research – References Abstract The seafarers’ labour market is exposed to continuous changes in terms of requested skills. This trend imposes to seafarers a growing flexibility to face the changing factors that characterize the maritime and logistics cluster. These rapid changes in requested competences, jointly with severe working conditions at sea, lead seafarers to reasoning on potential job opportunities, for an ashore “second life”. The paper provides an overview of seafarers’ hard and soft skills. Then it proposes an ad-hoc framework for disentangling main issues related to competences in the shipping industry. Finally, the theoretical model proposed is used for scrutinizing those skills developed aboard that are expected to support ex-seafarers when searching satisfactory jobs ashore. The manuscript investigates skills in the maritime sector for the development of our conceptual framework. Moreover, it tests and validates this conceptual model, grounding on both anecdotal evidences and insights from experts and practitioners involved in the industry. Key words: Seafarer, Soft and hard skills, Human resources management * Teresina Torre, Full Professor, Department of Economics and Business Studies, University of Genoa (Italy), E-mail [email protected] ** Marta Giannoni, Research Fellow, Italian Centre of Excellence in Logistics Transport and Infrastructures (CIELI) - University of Genoa (Italy), E-mail [email protected] *** Giovanni Colzi, Former Navy Officer, E-mail [email protected] Received 14th August 2019; accepted 9th December 2019. -

J. Lauritzen Full Article Language: En Indien Anders: Engelse Articletitle: 0

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en nul 0 in hierna): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (oude _articletitle_deel, vul hierna in): J. Lauritzen _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 96 Chapter 5 Chapter 5 J. Lauritzen In 1884, the consul Ditlev Lauritzen (1859-1935) moved from his hometown Ribe in Western Denmark to Esbjerg to start the company J. Lauritzen1. The company was named after Ditlev’s father since Ditlev was under 25 years old and not of age to start a business. He started an import business with wood, coal and fodder. He began with chartered ships for his imports but bought a few ships in late 1880s and could call himself a ship-owner. In 1895, the newly started shipowning company Vesterhavet, had a fleet of three ships. The fleet grew remarkably, and merely five years later, another seven ships had been added to the fleet. Lauritzen was both a shipowner and a shipbroker until 1918 when he closed down his shipbroking office. Apart from shipping, many of Lauritzen’s businesses were onshore. The Ditlev Lauritzen as portrayed by re- searcher Ole Lange is a truly dynamic entrepreneur, constantly on the move, catching new opportunities wherever they would arise. But it was the shipping business that was the core, and more precisely the transportation of coal, wood and cotton. By the end of 1914, the fleet comprised 26 ships. At about that time, the headquarters moved to Copenhagen. Sometimes Lauritzen’s ships carried fruit as a backhaul cargo – the first shipment of oranges was from the Spanish Mediterranean coast to England in a conventional general cargo vessel in 1905. -

M. NOTICE RLM-118 Rev. 02/2021 FEE SCHEDULE ANNEX 5 (A

FEE SCHEDULE ANNEX 5 (a) Charge for submitting paper applications per application; this does not include charges for secure handling and processing ............................................................... $100 (b) For all officer’s navigational and engineering licenses .............................................. $275 (c) First and Second Class Radio Electronic Operator-GMDSS ..................................... $275 (d) Examination Fee for any Navigational, Engineering or MOU Officer exam ............ $275 (e) Certification Fee for Officer’s License after successfully completing Liberian Officer’s Examination .................................................................................. $275 (f) Re-examination Fee after failure of one or more sections of Liberian Officer examination .................................................................................................... $275 (g) Translation Fee for examination, if taken in any language other than English ........................................................................................................................ $100 (h) For license renewal .................................................................................................... $275 (i) For issuance of Certificate of Receipt of Application (if done by the agent) ................ $40 If done by Seafarer’s Documentation Department Client Services Staff .................... $50 (j) For replacement of lost officer certificate ................................................................. -

49 CFR Ch. X (10–1–10 Edition) § 1245.5

erowe on DSK5CLS3C1PROD with CFR VerDate Mar<15>2010 08:56 Nov 10,2010 Jkt220220 PO00000 Frm00204 Fmt8010 Sfmt8010 Y:\SGML\220220.XXX 220220 § 1245.5 § 1245.5 Classification of job titles. Number Classification Description Typical titles Relation to present classification 100 EXECUTIVES, OFFICIALS, AND STAFF ASSISTANTS 101 Executives and General Officers Chief executives, corporate de- President, Vice President, Assistant Vice President, Controller, More precisely defined than present partment heads and major Treasurer, Director (head of subdepartment), General Super- No. 1, limited to executive manage- subdepartment heads. intendent (subdepartment head), Chief Engineer, General Man- ment positions; adds new titles. ager (department or subdepartment head). 102 Corporate Staff Managers .......... Corporate executives and man- Director (other than subdepartment head), Assistant Director, As- New classification, providng a specific agers assisting department sistant General Manager (not regional), Manager, Assistant assignment for staff managers; adds and subdepartment heads. Manager, Assistant Chief Engineer, Purchasing Agent, Super- new title. intendent (not division), Assistant to (corporate executive or general officer), Executive Assistant (to corporate executive) Budget Officer. 103 Regional and Division Officers, Regional managers and assist- Assistant General Manager, Assistant Regional Manager, Gen- Similar to present No. 2 but limited to Assistants and Staff Assist- ants below the executive man- eral Superintendent, Assistant to General Manager, Division regional and divisional management; ants. agement level, and chief divi- Superintendent, Master Mechanic, Division Sales Manager, adds new title. sion officers. District Sales Manager, Assistant Master Mechanic, District En- gineer, Assistant Superintendent, Captain of Police, Division Engineer, Manager of Materials, Safety Inspector, Real Estate 194 Agent, Real Estate Supervisor, Tax Agent, Buyer, Assistant Buyer, Sales Agent, Assistant Sales Agent. -

Subchapter B—Merchant Marine Officers and Seamen

SUBCHAPTER B—MERCHANT MARINE OFFICERS AND SEAMEN PART 10—LICENSING OF MARITIME 10.304 Substitution of training for required service, use of training-record books, and PERSONNEL use of towing officer assessment records. 10.305 Radar-Observer certificates and Subpart A—General qualifying courses. 10.306 [Reserved] Sec. 10.307 Training schools with approved radar 10.101 Purpose of regulations. observer courses. 10.102 National Maritime Center. 10.309 Coast Guard-accepted training other 10.103 Incorporation by reference. than approved courses. 10.104 Definitions of terms used in this part. 10.105 Applications. 10.107 Paperwork approval. Subpart D—Professional Requirements for 10.109 Fees. Deck Officers’ Licenses 10.110 Fee payment procedures. 10.401 Ocean and near coastal licenses. 10.111 Penalties. 10.402 Tonnage requirements for ocean or 10.112 No-fee license for certain applicants. near coastal licenses for vessels of over 10.113 Transportation Worker Identification 1600 gross tons. Credential. 10.403 Structure of deck licenses. Subpart B—General Requirements for All 10.404 Service requirements for master of ocean or near coastal steam or motor Licenses and Certificates of Registry vessels of any gross tons. 10.201 Eligibility for licenses and certifi- 10.405 Service requirements for chief mate cates of registry, general. of ocean or near coastal steam or motor 10.202 Issuance of licenses, certificates of vessels of any gross tons. registry, and STCW certificates or en- 10.406 Service requirements for second mate dorsements. of ocean or near coastal steam or motor 10.203 Quick reference table for license and vessels of any gross tons. -

Alfons Håkans History 1896 -1930’S

Alfons Håkans history 1896 -1930’s In 1896, Johannes Håkans, a farmer from Strandas, established a small steam sawmill. The sawmill’s production was modest at first and mainly consisted of sawing timber in order to build houses. However, tragedy struck in 1897 when the mill burnt down, believed to be the work of an arsonist. What was left of the burnt sawmill & property were sold and Johannes emigrated to the USA. It was during this time that the steam sawmill was put back into operation and it even expanded to incorporate a forage and planning mill. Johannes returned to Finland and in 1905 he bought back the mill. The company was registered as a limited company in 1910 and during the next 5 years the first tugs, Leo and Tor, were purchased and were used for shipping timber to the mill. In the 1920s, Johannes’s son, Alfons Håkans, joined the family business. More tugs and pontoons were purchased, among them Kraft and Hurtig (built 1920-21) to name but a few. As a tribute to the early years of the company, several old names are still in use on the modern tugs. Hard times struck again in the 1920s with two devastating fires at the sawmill in addition to the world-wide recession that lasted from 1929 until 1932. However, the company made progress as well, one example being the successful salvage of the Greek 10,000tdw steamship ‘Diamantis’ in 1929. The salvage took place off the rocks of Norrskär Island, just outside the Port of Vaasa and Alfons worked as a diver during the salvage. -

MARINA Circular No. 2012

Republic of the Philippines Department of Transportation and Communications MARITIME INDUSTRY AUTHORITY MARINA CIRCULAR NO. 2012 - 06 TO : ALL DOMESTIC SHIPPING COMPANIES AND OTHER MARITIME ENTITIES CONCERNED SUBJECT : REVISED MINIMUM SAFE MANNING FOR SHIPS OPERATING IN PHILIPPINE DOMESTIC WATERS Pursuant to the provisions of International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW) 1978, as amended; International Maritime Organization Resolution A.1047 (27) – Principles of Safe Manning; Regulation 14 (1), Chapter V of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1974 (SOLAS), as amended; Philippine Merchant Marine Rules and Regulation (PMMRR) 1997, as amended; Executive Order 125/125-A, and Republic Act 9295, the following revised guidelines on the issuance of Minimum Safe Manning Certificate are hereby prescribed. I. OBJECTIVE: To ensure that all Philippine-registered ships are manned by a sufficient number of qualified, competent and certificated officers and ratings who can safely operate the ship at all times in accordance with the herein provisions. II. COVERAGE This Circular shall apply to all Philippine-registered ships operating in the domestic waters. III. DEFINITION OF TERMS: For purposes of this Circular, the following terms are defined: 1. "Administration" means the Maritime Industry Authority. 2. "Boat Captain 1" refers to a Marine Deck Officer duly licensed by the MARINA to command a ship 15 GT and below. 3. "Boat Captain 2" refers to a Marine Deck Officer duly licensed by the MARINA to command a ship below 35 GT. 4. "Boat Captain 3" refers to a Marine Deck Officer duly licensed by the MARINA to command a ship below 100 GT.