Sturnid Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table 7: Species Changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015)

IUCN Red List version 2015.4: Table 7 Last Updated: 19 November 2015 Table 7: Species changing IUCN Red List Status (2014-2015) Published listings of a species' status may change for a variety of reasons (genuine improvement or deterioration in status; new information being available that was not known at the time of the previous assessment; taxonomic changes; corrections to mistakes made in previous assessments, etc. To help Red List users interpret the changes between the Red List updates, a summary of species that have changed category between 2014 (IUCN Red List version 2014.3) and 2015 (IUCN Red List version 2015-4) and the reasons for these changes is provided in the table below. IUCN Red List Categories: EX - Extinct, EW - Extinct in the Wild, CR - Critically Endangered, EN - Endangered, VU - Vulnerable, LR/cd - Lower Risk/conservation dependent, NT - Near Threatened (includes LR/nt - Lower Risk/near threatened), DD - Data Deficient, LC - Least Concern (includes LR/lc - Lower Risk, least concern). Reasons for change: G - Genuine status change (genuine improvement or deterioration in the species' status); N - Non-genuine status change (i.e., status changes due to new information, improved knowledge of the criteria, incorrect data used previously, taxonomic revision, etc.); E - Previous listing was an Error. IUCN Red List IUCN Red Reason for Red List Scientific name Common name (2014) List (2015) change version Category Category MAMMALS Aonyx capensis African Clawless Otter LC NT N 2015-2 Ailurus fulgens Red Panda VU EN N 2015-4 -

The Use of Starlicide in Preliminary Trials to Control Invasive Common

Conservation Evidence (2010) 7, 52-61 www.ConservationEvidence.com The use of Starlicide ® in preliminary trials to control invasive common myna Acridotheres tristis populations on St Helena and Ascension islands, Atlantic Ocean Chris J. Feare WildWings Bird Management, 2 North View Cottages, Grayswood Common, Haslemere, Surrey GU27 2DN, UK Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY Introduced common mynas Acridotheres tristis have been implicated as a threat to native biodiversity on the oceanic islands of St Helena and Ascension (UK). A rice-based bait treated with Starlicide® was broadcast for consumption by flocks of common mynas at the government rubbish tips on the two islands during investigations of potential myna management techniques. Bait was laid on St Helena during two 3-day periods in July and August 2009, and on Ascension over one 3-day period in November 2009. As a consequence of bait ingestion, dead mynas were found, especially under night roosts and also at the main drinking area on Ascension, following baiting. On St Helena early morning counts at the tip suggested that whilst the number of mynas fell after each treatment, lower numbers were not sustained; no reduction in numbers flying to the main roost used by birds using the tip as a feeding area was detected post-treatment. On Ascension, the number of mynas that fed at the tip and using a drinking site, and the numbers counted flying into night roosts from the direction of the tip, both indicated declines of about 70% (from about 360 to 109 individuals). Most dead birds were found following the first day of bait application, with few apparently dying after baiting on days 2 and 3. -

A Complete Species-Level Molecular Phylogeny For

Author's personal copy Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 47 (2008) 251–260 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev A complete species-level molecular phylogeny for the ‘‘Eurasian” starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnus, Acridotheres, and allies): Recent diversification in a highly social and dispersive avian group Irby J. Lovette a,*, Brynn V. McCleery a, Amanda L. Talaba a, Dustin R. Rubenstein a,b,c a Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, Laboratory of Ornithology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14950, USA b Department of Neurobiology and Behavior, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14850, USA c Department of Integrative Biology and Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Received 2 August 2007; revised 17 January 2008; accepted 22 January 2008 Available online 31 January 2008 Abstract We generated the first complete phylogeny of extant taxa in a well-defined clade of 26 starling species that is collectively distributed across Eurasia, and which has one species endemic to sub-Saharan Africa. Two species in this group—the European starling Sturnus vulgaris and the common Myna Acridotheres tristis—now occur on continents and islands around the world following human-mediated introductions, and the entire clade is generally notable for being highly social and dispersive, as most of its species breed colonially or move in large flocks as they track ephemeral insect or plant resources, and for associating with humans in urban or agricultural land- scapes. Our reconstructions were based on substantial mtDNA (4 kb) and nuclear intron (4 loci, 3 kb total) sequences from 16 species, augmented by mtDNA NDII gene sequences (1 kb) for the remaining 10 taxa for which DNAs were available only from museum skin samples. -

Traffic.Org/Home/2015/12/4/ Thousands-Of-Birds-Seized-From-East-Java-Port.Html

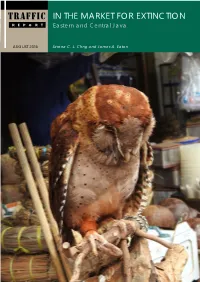

TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION REPORT Eastern and Central Java AUGUST 2016 Serene C. L. Chng and James A. Eaton TRAFFIC Report: In The Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java 1 TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC. Southeast Asia Regional Office Unit 3-2, 1st Floor, Jalan SS23/11 Taman SEA, 47400 Petaling Jaya Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. © TRAFFIC 2016. ISBN no: 978-983-3393-50-3 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722. Suggested citation: Chng, S.C.L. and Eaton, J.A. (2016). In the Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java. TRAFFIC. Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Front cover photograph: An Oriental Bay Owl Phodilus badius displayed for sale at Malang Bird Market Credit: Heru Cahyono/TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION Eastern and Central Java Serene C. -

Common Diseases of Gamebirds in Great Britain

Common diseases of gamebirds in Great Britain In the summer months gamebird flocks may During the rearing stage, growing gamebirds are experience health problems and veterinarians given access to an outside run attached to a may be presented with pheasants, partridges, or brooder pen/house. At this stage, development of other gamebirds. It is therefore important to be a good quality, complete and waterproof aware of and consider some of the common feathering is essential for gamebirds to endure gamebird diseases to aid the investigation and adverse weather conditions. Feather pecking and differential diagnosis of such health problems. aggression between gamebirds poults may have a significant impact on plumage quality. Stocking Health problems during the first three weeks rates, boredom/stress, ill-health, unbalanced diets of life and poor management may be contributory Rotavirus infection is commonly seen in factors that can lead to feather pecking and have pheasants and partridges as the cause of illness, a detrimental effect on birds’ plumage. diarrhoea and death, mostly between the ages of Motile protozoa: Spironucleus meleagridis 4 and 14 days. Grossly, there is distension of the (Hexamita) and Tetratrichomonas gallinarum are intestinal tract and caeca by frothy yellow fluid. motile protozoa that commonly cause health Secondary bacterial infections may cause problems in gamebirds, notably diarrhoea and pericarditis, perihepatitis, hepatomegaly or mortality, during the summer months. S. splenomegaly. Usually, gamebirds are affected by meleagridis has whip-like flagella and is highly group A rotaviruses, but non-group A (atypical) motile with a quick jerky action. In contrast, T. rotavirus infections also occur. Rotavirus detection gallinarum is longer and moves more slowly and is usually by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis smoothly. -

Government of the Republic of Sierra Leone Bumbuna Hydroelectric

Government of the Republic of Sierra Leone Ministry of Energy and Power Public Disclosure Authorized Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project Environmental Impact Assessment Draft Final Report - Appendices Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized January 2005 Public Disclosure Authorized in association with BMT Cordah Ltd Appendices Document Orientation The present EIA report is split into three separate but closely related documents as follows: Volume1 – Executive Summary Volume 2 – Main Report Volume 3 – Appendices This document is Volume 3 – Appendices. Nippon Koei UK, BMT Cordah and Environmental Foundation for Africa i Appendices Glossary of Acronyms AD Anno Domini AfDB African Development Bank AIDS Auto-Immune Deficiency Syndrome ANC Antenatal Care BCC Behavioural Change Communication BHP Bumbuna Hydroelectric Project BWMA Bumbuna Watershed Management Authority BOD Biochemical Oxygen Demand BP Bank Procedure (World Bank) CBD Convention on Biodiversity CHC Community Health Centre CHO Community Health Officer CHP Community Health Post CLC Community Liaison Committee COD Chemical Oxygen Demand dbh diameter at breast height DFID Department for International Development (UK) DHMT District Health Management Team DOC Dissolved Organic Carbon DRP Dam Review Panel DUC Dams Under Construction EA Environmental Assessment ECA Export Credit Agency EFA Environmental Foundation for Africa EHS Environment, Health and Safety EHSO Environment, Health and Safety Officer EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EPA -

Lesser Blue-Eared Starling 14˚ Klein-Blouoorglansspreeu L

472 Sturnidae: starlings and mynas Lesser Blue-eared Starling 14˚ Klein-blouoorglansspreeu L. BLUE−EARED STARLING Lamprotornis chloropterus 1 5 The Lesser Blue-eared Starling is widespread in 18˚ Africa south of the Sahara, but in southern Africa it is confined to northeastern regions. There has been a series of reports from along the Limpopo Valley and catchment in both Zimbabwe and the 22˚ Transvaal, but only one has been accepted here. An 6 authenticated sighting was made near Punda Maria 2 (2331AA) in January 1995 (Hockey et al. 1996). In northern Zimbabwe it is the commonest glossy 26˚ starling but in the drier south, the Greater Blue- eared Starling L. chalybaeus is more numerous (Irwin 1981). It is inclined to form much larger flocks than either of the other two common glossy 3 7 starlings, but combined parties may be found from 30˚ time to time. Glossy Starlings have always created identifi- cation problems in the field; the Lesser Blue-eared 4 8 Starling in particular is likely to have suffered from 34˚ misidentification. The enormous scatter in the 18˚ 22˚ 26˚ reporting rates in the model for Zone 5 is testimony 10˚ 14˚ 30˚ 34˚ to the inconsistency and lack of confidence be- devilling the recording of this species. It is essentially a bird of miombo woodlands, occasionally Recorded in 177 grid cells, 3.9% wandering into adjacent woodland types. In the Caprivi Strip Total number of records: 1778 it may be found in the intermixed Arid Woodland, Mopane Mean reporting rate for range: 26.4% and Okavango vegetation types, and there are a few records from adjacent Botswana (Borello 1992b; Penry 1994). -

Acridotheres Tristis Linnaeus, 1766 the Common Myna (Acridotheres Tristis) Is a Highly Commensal Passerine That Lives in Close Association with Humans

Acridotheres tristis Linnaeus, 1766 The common myna (Acridotheres tristis) is a highly commensal Passerine that lives in close association with humans. It competes with small mammals and birds for nesting hollows and on some islands, such as Hawaii and Fiji, it preys on other birds’ eggs and chicks. It presents a threat to indigenous biota, particularly parrots and other birdlife, in Australia and elsewhere. The common myna has been introduced to parts of South East Asia, New Zealand, eastern Australia and southern Africa and Madagascar. It is also present on many islands in the Atlantic Ocean (including the Canary Islands, St Helena and Ascension Island), Indian Ocean (including Réunion, Mauritius, Rodriguez north to Lacadive and Maldive Islands and east to Andaman and Solomon Islands, Samoa, Cook Islands, Society Islands and some otherNicobar French Islands) Polynesian and Pacific islands). Ocean There (including are new Fiji, recordsNew Caledonia, of both the common myna and the jungle myna (Acridotheres fuscus) on tropical islands, most recently on Kiribati. Photo credit: K.W Bridges [link] Besides destroying fruit crops and being a public nuisance (they are highly vocal birds), the common myna is a nest site competitor. A Risk assessment model by the Bureau of Rural Sciences, Australia, On the Comoros, mynas are known to compete for nest holes with the ‘Critically Endangered (CR)’ Anjouan Scops Owl (Otus 2003). Foraging traps are very useful for the control of small myna capnodes) and the Grand Comoro Scops owl (Otus pauliani). On populationsclassifies the ifcommon poisoning myna is notin the an highest option. threat Starlacide category DRC1339 (Bomford has Saint Helena, cats and the common myna are probably the most been used against mynas and is effective where there are no non- target species issues. -

Prevalence of Chlamydia Psittaci in Domesticated and Fancy Birds in Different Regions of District Faisalabad, Pakistan

United Journal of Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Research Article Prevalence of Chlamydia Psittaci in Domesticated and Fancy Birds in Different Regions of District Faisalabad, Pakistan Siraj I1, Rahman SU1, Ahsan Naveed1* Anjum Fr1, Hassan S2, Zahid Ali Tahir3 1Institute of Microbiology, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad 2Institute of Animal Nutrition and Feed Technology, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Pakistan 3DiagnosticLaboraoty, Kamalia, Toba Tek Singh, Pakistan Volume 1 Issue 1- 2018 1. Abstract Received Date: 15 July 2018 1.1. Introduction Accepted Date: 31 Aug 2018 The study was aimed to check the prevalence of this zoonotic bacterium which is a great risk Published Date: 06 Sep 2018 towards human population in district Faisalabad at Pakistan. 1.2. Methodology 2. Key words Chlamydia Psittaci; Psittacosis; In present study, a total number of 259 samples including fecal swabs (187) and blood samples Prevalence; Zoonosis (72) from different aviculture of 259 birds such as chickens, ducks, pigeons, parrots, Australian parrots, and peacock were collected from different regions of Faisalabad, Pakistan. After process- ing the samples were inoculated in the yolk sac of embryonated chicken eggs for the cultivation ofChlamydia psittaci(C. psittaci)and later identified through Modified Gimenez staining and later CFT was performed for the determination of antibodies titer against C. psittaci. 1.3. Results The results of egg inoculation and modified Gimenez staining showed 9.75%, 29.62%, 10%, 36%, 44.64% and 39.28% prevalence in the fecal samples of chickens, ducks, peacocks, parrots, pi- geons and Australian parrots respectively. Accordingly, the results of CFT showed 15.38%, 25%, 46.42%, 36.36% and 25% in chickens, ducks, pigeons, parrots and peacock respectively. -

Programs and Field Trips

CONTENTS Welcome from Kathy Martin, NAOC-V Conference Chair ………………………….………………..…...…..………………..….…… 2 Conference Organizers & Committees …………………………………………………………………..…...…………..……………….. 3 - 6 NAOC-V General Information ……………………………………………………………………………………………….…..………….. 6 - 11 Registration & Information .. Council & Business Meetings ……………………………………….……………………..……….………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…………………………………..…..……...….. 11 6 Workshops ……………………….………….……...………………………………………………………………………………..………..………... 12 Symposia ………………………………….……...……………………………………………………………………………………………………..... 13 Abstracts – Online login information …………………………..……...………….………………………………………….……..……... 13 Presentation Guidelines for Oral and Poster Presentations …...………...………………………………………...……….…... 14 Instructions for Session Chairs .. 15 Additional Social & Special Events…………… ……………………………..………………….………...………………………...…………………………………………………..…………………………………………………….……….……... 15 Student Travel Awards …………………………………………..………...……………….………………………………..…...………... 18 - 20 Postdoctoral Travel Awardees …………………………………..………...………………………………..……………………….………... 20 Student Presentation Award Information ……………………...………...……………………………………..……………………..... 20 Function Schedule …………………………………………………………………………………………..……………………..…………. 22 – 26 Sunday, 12 August Tuesday, 14 August .. .. .. 22 Wednesday, 15 August– ………………………………...…… ………………………………………… ……………..... Thursday, 16 August ……………………………………….…………..………………………………………………………………… …... 23 Friday, 17 August ………………………………………….…………...………………………………………………………………………..... 24 Saturday, -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

Lambusango Forest Conservation Project Research Proposal 2008

Lambusango Forest Research Project OPERATION WALLACEA Research Report 2011 Compiled by Dr Philip Wheeler (email [email protected]) University of Hull Scarborough Campus, Centre for Environmental and Marine Sciences Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Research Sites ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Research activity 2011 ............................................................................................................................ 3 Monitoring bird communities............................................................................................................. 4 Bat community dynamics ................................................................................................................... 9 Monitoring herpetofauna and small mammal communities ........................................................... 11 Butterfly community dynamics ........................................................................................................ 15 Monitoring anoa and wild pig populations ...................................................................................... 19 Habitat associations and sleeping site characteristics