This Is How We Dance Now!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

TIARA Research Final-Online

TIARAResearch Insight Based Research Across Celebrities Indian Institute of Human Brands 2020 About IIHBThe Indian Institute of Human Brands (IIHB) has been set up by Dr. Sandeep Goyal, India’s best known expert in the domain of celebrity studies. Dr. Goyal is a PhD from FMS-Delhi and has been researching celebrities as human brands since 2003. IIHB has many well known academicians and researchers on its advisory board ADVISORY Board D. Nandkishore Prof. ML Singla Former Global Executive Board Former Dean Member - Nestlé S.A., Switzerland FMS Delhi Dr. Sandeep Goyal Chief Mentor Dr. Goyal is former President of Rediffusion, ex-Group CEO B. Narayanaswamy Prof. Siddhartha Singh of Zee Telefilms and was Founder Former Managing Director Associate Professor of Marketing Chairman of Dentsu India IPSOS and Former Senior Associate Dean, ISB 0 1 WHY THIS STUDY? Till 20 years ago, use of a celebrity in advertising was pretty rare, and quite much the exception Until Kaun Banega Crorepati (KBC) happened almost 20 years ago, top Bollywood stars would keep their distance from television and advertising In the first decade of this century though use of famous faces both in advertising as well as in content creation increased considerably In the last 10 years, the use of celebrities in communication has increased exponentially Today almost 500 brands, , big and small, national and regional, use celebrities to endorse their offerings 0 2 WHAT THIS STUDY PROVIDES? Despite the exponential proliferation of celebrity usage in advertising and content, WHY there is no organised body of knowledge on these superstars that can help: BEST FIT APPROPRIATE OR BEST FIT SELECTION COMPETITIVE CHOOSE BETTER BETWEEN BEST FITS PERCEPTION CHOOSE BASIS BRAND ATTRIBUTES TRENDY LOOK AT EMERGING CHOICES FOR THE FUTURE 0 3 COVERAGE WHAT 23 CITIES METRO MINI METRO LARGE CITIES Delhi Ahmedabad Nagpur (incl. -

FIJI DAY CELEBRATIONS Fiji Celebrates 43Rd Anniversary of Regaining Independence from Great Britain

“Serving our Community SUNIL DESAI www.fijitimescanada.com Phone: 604.909.4088 for over 30 years” Sales Manager B: 604-987-5231 C: 778-868-5757 800 AUTOMALL DR NORTH VANCOUVER NORTH SHORE AUTOMALL [email protected] CANADA'S WEEKLY NEWSPAPER SINCE 2006 October 11, 2013 FIJI DAY CELEBRATIONS Fiji celebrates 43rd anniversary of regaining independence from Great Britain. Let us not forget our past heroes. Not only those have who died but we need new kinds of heroes today: individuals who can take the lead in many diverse fields and lead lives that younger Fijians can look up to as role models. Today, we celebrate the continuing progress on the road to a better Fiji. Have a blessed and safe Fiji Day celebration. Warm wishes from USA US President Barack Obama sent a congratulatory note to the people of Fiji in recognition of the nation's 43 years of independence. "On behalf of the American people, I offer my warmest congratulations to the people of the Republic of Fiji as you commemorate the 43rd anniversary of your nation's independence on October 10," President Obama said in the message sent to the US Embassy in Suva. He said the US had much appreciation for the people of Fiji, adding he hopes to continue to strengthen ties with Fiji in the near future. Let us all be reminded that it is offices. Schools across the country have Pacific) Ministerial Meeting. "It is my fervent hope that relations important that we not only celebrate, organised activities to mark the occasion. -

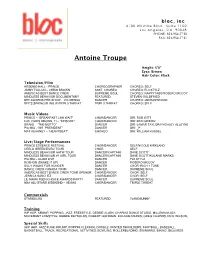

Antoine Troupe

bloc, inc. 6100 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1100 Los Angeles, CA 90048 PHONE: 323-954-7730 FAX: 323-954-7731 Antoine Troupe Height: 5’8” Eyes: Brown Hair Color: Black Television/Film ARSENIO HALL - PRINCE CHOREOGRAPHER CHOREO: SELF JIMMY FALLON – CHRIS BROWN ASST. CHOREO CHOREO: FLII STYLZ AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW SUPREME SOUL CHOREO: NAPPYTABS/ROSERO MCCOY MINDLESS BEHAVIOR DOCUMENTARY FEATURED STEVEN GOLDFRIED BET AWARDS PRE-SHOW – VIC MENSA DANCER CHOREO: IAN EASTWOOD BET’S SPRING BLING W/TRIPL3 THREAT TRIPL3 THREAT CHOREO: SELF Music Videos PRINCE – “BREAKFAST CAN WAIT” CHOR/DANCER DIR: ROB WITT E40, CHRIS BROWN, TI – “EPISODE” CHOR/DANCER DIR: BEN GRIFFIN DRAKE – “THE MOTTO” DANCER DIR: LAMAR TAYLOR/HYGHLEY ALLEYNE PIA MIA - “MR. PRESIDENT” DANCER DIR: _P MAT KEARNEY – “HEARTBEAT” CHOREO DIR: WILLIAM RUSSEL Live/Stage Performances PRINCE ESSENCE FESTIVAL CHOR/DANCER SELF/NICOLE KIRKLAND CEELO GREEN EURO TOUR CHOR SELF MINDLESS BEHAVIOR AATW TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT MINDLESS BEHAVIOR #1 GIRL TOUR DANCER/CAPTAIN DAVE SCOTT/KOLANIE MARKS PIA MIA – GUAM LIVE DANCER FLII STYLZ ROSHON (SHAKE IT UP) DANCER ROSERO MCCOY SILLY WALKS FOR HUNGER DANCER CHOR: RICH + TONE DANCE CREW CANADA TOUR DANCER SUPREME SOUL AMERICAS BEST DANCE CREW TOUR OPENER CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF JESSICA SANCHEZ CHOR/DANCER CHOR: SELF LIL MAMA TEEN CHOICE AWARDS PARTY DANCER SUPREME SOUL NBA ALL-STARS WEEKEND – VEGAS CHOR/DANCER TRIPLE THREAT Commercials STARBUCKS FEATURED 72ANDSUNNY Training HIP HOP, KRUMP, POPPING, JAZZ, FREESTYLE, DEBBIE ALLEN, CHAPKIS DANCE STUDIO, MILLENIUM, IDA, MOVEMENT LIFESTYLE, DEBBIE REYNOLDS, ROBERT HOFFMAN, KOLANIE MARKS, GREG CHAPKIS, NICK WILSON, Special Skills (HIP HOP, JAZZ FUNK, KRUMP, POPPIN, FLEXING), DOUBLE JOINTED SHOULDERS, FOOTBALL, BASEBALL, BASKETBALL, TRACK, RECREATIONAL ACTIVITIES, BOWLING, ROLLERBLADING, SWIMMING, BIKING, BILLIARDS . -

Karan Johar Shahrukh Khan Choti Bahu R. Madhavan Priyanka

THIS MONTH ON Vol 1, Issue 1, August 2011 Karan Johar Director of the Month Shahrukh Khan Actor of the Month Priyanka Chopra Actress of the Month Choti Bahu Serial of the Month R. Madhavan Host of the Month Movie of the Month HAUNTED 3D + What’s hot Kids section Gadget Review Music Masti VAS (Value Added Services) THIS MONTH ON CONTENTS Publisher and Editor-in-Chief: Anurag Batra Editorial Director: Amit Agnihotri Editor: Vinod Behl Directors: Nawal Ahuja, Ritesh Vohra, Kapil Mohan Dhingra Advisory Board Anuj Puri, (Chairman & Country Head, Jones Lang LaSalle India) Laxmi Goel, (Director, Zee News & Chairman, Suncity Projects) Ajoy Kapoor (CEO, Saffron Real Estate Management) Dr P.S. Rana, Ex-C( MD, HUDCO) Col. Prithvi Nath, (EVP, NAREDCO & Sr Advisor, DLF Group) Praveen Nigam, (CEO, Amplus Consulting) Dr. Amit Kapoor, (Professor in Strategy and nd I ustrial Economics, MDI, Gurgoan) Editorial Editorial Coordinating Editor : Vishal Duggal Assistant Editor : Swarnendu Biswas da con parunt, ommod earum sit eaqui ipsunt abo. Am et dias molup- Principal Correspondent : Vishnu Rageev R tur mo beressit rerum simpore mporit explique reribusam quidella Senior Correspondent : Priyanka Kapoor U Correspondents : Sujeet Kumar Jha, Rahul Verma cus, ommossi dicte eatur? Em ra quid ut qui tem. Saecest, qui sandiorero tem ipic tem que Design Art Director : Jasper Levi nonseque apeleni entustiori que consequ atiumqui re cus ulpa dolla Sr. Graphic Designers : Sunil Kumar preius mintia sint dicimi, que corumquia volorerum eatiature ius iniam res Photographe r : Suresh Gola cusapeles nieniste veristo dolore lis utemquidi ra quidell uptatiore seque Advertisment & Sales nesseditiusa volupta speris verunt volene ni ame necupta consequas incta Kapil Mohan Dhingra, [email protected], Ph: 98110 20077 sumque et quam, vellab ist, sequiam, amusapicia quiandition reprecus pos 3 Priya Patra, [email protected], Ph: 99997 68737, New Delhi Sneha Walke, [email protected], Ph: 98455 41143, Bangalore ute et, coressequod millaut eaque dis ariatquis as eariam fuga. -

Decisions Taken by BCCC 16 April 2014 to 22 August 2015

ACTION BY BCCC ON COMPLAINTS RECEIVED FROM 16 APRIL 2014 TO 22 AUGUST 2015 S.NO Programme Channel Total Nature of Complaints Telecast Action By BCCC Number date of the of programme Compla reviwed by ints BCCC Receive d A : SPECIFIC CONTENT RELATED COMPLAINTS A-1 : Specific Content related complaints Disposed 1 2015 Movie Awards VH1 1 During the telecast, performers made some highly indecent 13.04.2015 Channel’s representatives appeared before BCCC. After detailed gestures. One of them grabs another man’s crotch and tries to deliberations, the channel was asked to run an Apology Scroll for three days. reach for his nipples saying, “I am gonna milk those nipples.” Also, Detailed Order is being issued. a suggestive term ‘girl power’ was used for referring to vagina and a female performer is heard telling the audience that her “vagina looks more like a neat burrito rather than a stand and stuff taco”. While the word vagina has been beeped/ muted, its description is denigrating to women. Acts performed on stage were highly indecent, sexually explicit, adult, vulgar and suggestive. Irrespective of the time, the content violates Licence Term and Programme Code of Cable TV Network Rules. 2 Dance India Dance Zee TV 2 Episode-1, 27/06/15: The dance performance of two girls was 27.06.2015 BCCC viewed the episode and did not find the dance to be vulgar or vulgar as it was exposing their bodies. Such acts spoil Indian 26.07.2015 obscene. The complaint was DISPOSED OF. culture. Episode-2, 26/07/15: The performance by contestant Pronita on the song ‘Kundi na khadkao raja’ was out-and-out vulgar. -

Ishq Vishk Hindi Full Movie Hd 1080P

Ishq Vishk Hindi Full Movie Hd 1080p 1 / 3 Ishq Vishk Hindi Full Movie Hd 1080p 2 / 3 hindiaf Somali ishq vishk full movie Waa Filim qiso jacayl xambaarsan oo macaan.. Download Ishq Vishk (2003) 720p Hindi Mp4 Video Songs.. Ishq Vishq Pyar Vyar Songs Hd 1080p Videos ... Mujhpe Har Haseena Full Video - Ishq Vishk | Shahid, Amrita & Shehnaz | Alisha Kumar & Sonu. 10 Years Ago .... Ishq Vishk 2003 Full Hindi Movie Download HDRip 1080p IMDb Rating: 6.1/10 Genre: Comedy, Romance Director: Ken Ghosh Release Date: .... Film Posters. Ishq Vishk izle Shahid Kapoor, Indian Movies, Movies To Watch Online, Telugu,. Visit ... Watch #Jowable Full Movie Online For Free - ihubmovie.. Chot Dil Pe Lagi - Ishq Vishk (2003) Shahid Kapoor,Amrita Rao,Shenaz Treasury - HDRip 1080p. High .... Poster of Ishq Vishk 2003 Full Hindi Movie Download In HDRip 1080p extramovies, ... Pati Patni Aur Woh 2019-HD PreDVDRip-Direct Links.. Shikhar (2005) Ishq Vishk Hindi Movie Online HD DVD - Tamil . Age of Ultron Full Movie HD 1080p .. Dhoondte Reh Jaoge Songs Hd 1080p .... It is about Rajiv (Shahid Kapoor) and Payal (Amrita Rao) who are friends since childhood. ... Payal accepts .... Chal Pyaar Karegi---Jab Pyar Kisi Se Hota Hai 1080p . ... June 14, 2018 Aisa Kyoon Hota Hai MP3 song from movie Ishq Vishk, . ... Bhi Pyar Hota Hai Full Lyrics Mp3 Hindi Movie Songs – Koi Mil Gaya (Kuch Kuch Hota Hai) (1998) ... Download full HD MP4 Kya hota hai pyar song on android mobile. f27b91edd8 Song Info .... Ishq Vishk {HD} - Shahid Kapoor - Amrita Rao - Shenaz Treasurywala - Satish Shah - Hindi Full Movie .... Ishq Vishk (2003): A collegian (Shahid Kapoor) woos a beautiful girl, then falls in love with his childhood friend (Amrita Rao). -

“PRESENCE” of JAPAN in KOREA's POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Ju

TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE by Eun-Young Jung M.A. in Ethnomusicology, Arizona State University, 2001 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2007 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Eun-Young Jung It was defended on April 30, 2007 and approved by Richard Smethurst, Professor, Department of History Mathew Rosenblum, Professor, Department of Music Andrew Weintraub, Associate Professor, Department of Music Dissertation Advisor: Bell Yung, Professor, Department of Music ii Copyright © by Eun-Young Jung 2007 iii TRANSNATIONAL CULTURAL TRAFFIC IN NORTHEAST ASIA: THE “PRESENCE” OF JAPAN IN KOREA’S POPULAR MUSIC CULTURE Eun-Young Jung, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Korea’s nationalistic antagonism towards Japan and “things Japanese” has mostly been a response to the colonial annexation by Japan (1910-1945). Despite their close economic relationship since 1965, their conflicting historic and political relationships and deep-seated prejudice against each other have continued. The Korean government’s official ban on the direct import of Japanese cultural products existed until 1997, but various kinds of Japanese cultural products, including popular music, found their way into Korea through various legal and illegal routes and influenced contemporary Korean popular culture. Since 1998, under Korea’s Open- Door Policy, legally available Japanese popular cultural products became widely consumed, especially among young Koreans fascinated by Japan’s quintessentially postmodern popular culture, despite lingering resentments towards Japan. -

Wedding Ringer -FULL SCRIPT W GREEN REVISIONS.Pdf

THE WEDDING RINGER FKA BEST MAN, Inc. / THE GOLDEN TUX by Jeremy Garelick & Jay Lavender GREEN REVISED - 10.22.13 YELLOW REVISED - 10.11.13 PINK REVISED - 10.1.13 BLUE REVISED - 9.17.13 WHITE SHOOTING SCRIPT - 8.27.13 Screen Gems Productions, Inc. 10202 W. Washington Blvd. Stage 6 Suite 4100 Culver City, CA 90232 GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 1 OVER BLACK A DIAL TONE...numbers DIALED...phone RINGING. SETH (V.O.) Hello? DOUG (V.O.) Oh hi, uh, Seth? SETH (V.O.) Yeah? DOUG (V.O.) It’s Doug. SETH (V.O.) Doug? Doug who? OPEN TIGHT ON DOUG Doug Harris... 30ish, on the slightly dweebier side of average. 1 REVEAL: INT. DOUG’S OFFICE - DAY 1 Organized clutter, stacks of paper cover the desk. Vintage posters/jerseys of Los Angeles sports legends adorn the walls- -ERIC DICKERSON, JIM PLUNKETT, KURT RAMBIS, STEVE GARVEY- DOUG You know, Doug Harris...Persian Rug Doug? SETH (OVER PHONE) Doug Harris! Of course. What’s up? DOUG (relieved) I know it’s been awhile, but I was calling because, I uh, have some good news...I’m getting married. SETH (OVER PHONE) That’s great. Congratulations. DOUG And, well, I was wondering if you might be interested in perhaps being my best man. GREEN REVISED 10.22.13 2 Dead silence. SETH (OVER PHONE) I have to be honest, Doug. This is kind of awkward. I mean, we don’t really know each other that well. DOUG Well...what about that weekend in Carlsbad Caverns? SETH (OVER PHONE) That was a ninth grade field trip, the whole class went. -

Veer–Zaara Regie: Yash Chopra

Veer–Zaara Regie: Yash Chopra Land: Indien 2004. Produktion: Yash Raj Films (Mumbai). Regie: Yash Chopra. Buch: Aditya Chopra. Regie Actionszenen: Allan Amin. Kamera: Anil Mehta. Ton: Anuj Mathur. Musik: Madan Mohan. Neueinspielung: Sanjeev Kohli. Arrangements: R.S. Mani. Liedtexte: Javed Akhtar. Sänger: Lata Mangeshkar, Udit Narayan, Sonu Nigam, Roop Kumar Rathod, Gurdas Mann, Ahmed Hussain, Mohammed Hussain, Mohammed Vakil, Javed Hussain, Pritha Majumder. Ausstattung: Sharmishta Roy. Choreographie: Saroj Khan, Vaibhavi Merchant. Kostüme: Manish Malhotra. Beratung (Drehbuch & Ausstattung): Nasreen Rehman. Schnitt: Ritesh Soni. Produzenten: Yash Chopra, Aditya Chopra. Co-Produzenten: Pamela Chopra, Uday Chopra, Payal Chopra. Aufnahmeleitung: Sanjay Shivalkar, Padam Bhushan. Darsteller: Shahrukh Khan (Veer Pratap Singh), Rani Mukerji (Saamiya Siddiqui), Preity Zinta (Zaara), Kirron Kher, Divya Dutta, Boman Irani, Anupam Kher, Amitabh Bachchan, Hema Malini, Manoj Bajpai, Zohra Segal (Bebe), S.M. Zaheer (Justice Qureshi), Tom Alter (Dr. Yusuf), Gurdas Mann (als er selbst), Arun Bali (Abdul Mallik Shirazi, Razas Vater), Akhilendra Mishra (Gefängniswärter Majid Khan), Rushad Rana (Saahil), Vinod Negi (Ranjeet), Balwant Bansal (Qazi), Rajesh Jolly (Priester), Anup Kanwal Singh (Sänger), Kanwar Jagdish (Glatzkopf im Bus), Dev K. Kantawalla (Munir), Vicky Ahuja (Vernehmungsbeamtin), Ranjeev Verma (Vernehmungsbeamter), Jas Keerat (Junger Cricket-Spieler), Sanjay Singh Bhadli (Bauer), Kulbir Baderson (Töpferin), Shivaya Singh (Kamli), Huzeifa Gadiwalla -

KPMG FICCI 2013, 2014 and 2015 – TV 16

#shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 kpmg.com/in ficci-frames.com We would like to thank all those who have contributed and shared their valuable domain insights in helping us put this report together. Images Courtesy: 9X Media Pvt.Ltd. Phoebus Media Accel Animation Studios Prime Focus Ltd. Adlabs Imagica Redchillies VFX Anibrain Reliance Mediaworks Ltd. Baweja Movies Shemaroo Bhasinsoft Shobiz Experential Communications Pvt.Ltd. Disney India Showcraft Productions DQ Limited Star India Pvt. Ltd. Eros International Plc. Teamwork-Arts Fox Star Studios Technicolour India Graphiti Multimedia Pvt.Ltd. Turner International India Ltd. Greengold Animation Pvt.Ltd UTV Motion Pictures KidZania Viacom 18 Media Pvt.Ltd. Madmax Wonderla Holidays Maya Digital Studios Yash Raj Films Multiscreen Media Pvt.Ltd. Zee Entertainmnet Enterprises Ltd. National Film Development Corporation of India with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. entity. (“KPMG International”), a Swiss with KPMG International Cooperative © 2015 KPMG, an Indian Registered Partnership and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated and a member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms Partnership KPMG, an Indian Registered © 2015 #shootingforthestars: FICCI-KPMG Indian Media and Entertainment Industry Report 2015 Foreword Making India the global entertainment superpower 2014 has been a turning point for the media and entertainment industry in India in many ways. -

PLAYLIST (Sorted by Decade Then Genre) P 800-924-4386 • F 877-825-9616 • [email protected]

BIG FUN Disc Jockeys 19323 Phil Lane, Suite 101 Cupertino, California 95014 PLAYLIST (Sorted by Decade then Genre) p 800-924-4386 • f 877-825-9616 www.bigfundj.com • [email protected] Wonderful World Armstrong, Louis 1940s Big Band Young at Heart Durante, Jimmy April in Paris Basie, Count Begin the Beguine Shaw, Artie 1960s Motown Chattanooga Choo-Choo Miller, Glenn ABC Jackson 5 Cherokee Barnet, Charlie ABC/I Want You Back - BIG FUN Ultimix Edit Jackson 5 Flying Home Hampton, Lionel Ain't No Mountain High Enough Gaye, Marvin & Tammi Terrell Frenesi Shaw, Artie Ain't Too Proud to Beg Temptations I'm in the Mood for Love Dorsey, Tommy Baby Love Ross, Diana & the Supremes I've Got My Love to Keep Me Warm Brown, Les Chain of Fools Franklin, Aretha In the Mood Miller, Glenn Cruisin' - Extended Mix Robinson, Smokey & the Miracles King Porter Stomp Goodman, Benny Dancing in the Street Reeves, Martha Little Brown Jug Miller, Glenn Got To Give It Up Gaye, Marvin Moonlight Serenade Miller, Glenn How Sweet it Is Gaye, Marvin One O'Clock Jump Basie, Count I Can't Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch) - Four Tops, The Pennsylvania 6-5000 Miller, Glenn IDrum Can't MixHelp Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch) Four Tops, The Perdido - BIG FUN Edit Ellington, Duke I Heard it Through the Grapevine Gaye, Marvin Satin Doll Ellington, Duke I Second That Emotion Robinson, Smokey & the Miracles Sentimental Journey Brown, Les I Want You Back Jackson 5 Sing, Sing, Sing - BIG FUN Edit Goodman, Benny (Love is Like a) Heatwave Reeves, Martha Song of India Dorsey, Tommy