Alessandro Deʼ Medici and the Question Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microfilms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)” . If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

Joinus in FLORENCE! Editor’S Note

77052 ISAKOS Winter 06 1/12/06 1:19 AM Page 1 ISAKOS newsletter The ISAKOS 6th Biennial Congress WINTER 2006 Volume 10, Issue 1 INSIDE THIS ISSUE Joinus IN FLORENCE! Editor’s Note ................................2 President’s Message ......................2 he Congress will bring together world leaders in arthroscopy, knee Traveling Fellowships......................3 surgery and orthopaedic sports Your Committees at Work ..............4 T medicine. Diverse and high quality 2007 Congress Awards..................6 presentations will include 200 scientific What are New Members Saying?....9 papers, discussions and debates, over 400 Teaching Center Spotlight ............10 electronic posters, technical exhibits, Workshop Series ..........................11 instructional course lectures and hands on workshops. Attendees from 70 different Current Concepts ........................12 countries are anticipated to attend the ISAKOS Meetings ......................17 ISAKOS Congress. In addition to the multi- ISAKOS Approved dimensional scientific program we hope Courses in Review........................18 you will attend the evening social events Maria Novella, is located near the Upcoming ISAKOS such as the Welcome Reception and Congress location, the Fortezza da Basso, Approved Courses ........................22 Farewell Banquet. and provides comfortable high-speed Florence is a city of sublime art trains with direct travel to Rome, Milan EDITOR and beauty, and casts a spell in a and Naples. Ronald M. Selby, MD, USA way few places can. Set in a valley on the The ISAKOS Congress will take place banks of the Arno, this captivating city is EDITORIAL BOARD within the Fortezza da Basso, a Medicean home to some of the most magnificent fortress built between 1533 and 1535 by Vladimir Bobic, MD FRCSEd, Renaissance masterpieces from United Kingdom Giuliano diSangallo. -

Galileo's Misstatements About Copernicus Author(S): Edward Rosen Source: Isis, Vol

The History of Science Society Galileo's Misstatements about Copernicus Author(s): Edward Rosen Source: Isis, Vol. 49, No. 3 (Sep., 1958), pp. 319-330 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/226939 Accessed: 13/04/2010 16:29 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and The History of Science Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Isis. http://www.jstor.org Galileo's Misstatementsabout Copernicus By Edward Rosen * A RECENT English translation 1 of selections from the writings of Galileo ( (564-I642) will doubtless bring to the attention of many readers the statements about Copernicus (I473-I543) in the great Italian scientist's Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina. -

Ambito N°7 PRATO E VAL DI BISENZIO

QUADRO CONOSCITIVO Ambito n°7 PRATO E VAL DI BISENZIO PROVINCE : Firenze , Prato TERRITORI APPARTENENTI AI COMUNI : Calenzano, Campi Bisenzio, Cantagallo, Carmignano, Montemurlo, Poggio a Caiano, Prato, Signa, Vaiano, Vernio COMUNI INTERESSATI E POPOLAZIONE I comuni sono tutti quelli della provincia di Prato - Cantagallo, Carmignano, Montemurlo, Poggio a Caiano, Prato, Vaiano, Vernio - e parte del territorio dei Comuni di Campi Bisenzio e Calenzano, nella provincia di Firenze. L’incremento della popolazione in 30 anni è poco meno del 26%, il più elevato fra le aree della Toscana. L’unico grande centro urbano è Prato, che era fino al 1991 la terza città della Toscana, e in seguito la seconda, avendo sorpassato Livorno. Gli altri comuni sono tutti in crescita, in vari casi hanno ripreso a crescere dopo fasi più o meno lunghe di calo. Ad esempio, Carmignano: cresce fino al 1911, quando Poggio a Caiano era una sua frazione, e sfiora i 9000 abitanti, e riprende poi una moderata crescita; Poggio a Caiano, formato nel 1962, è da allora in crescita sostenuta (nel 2001 ha il 190% della popolazione legale della frazione esistente nel 1951). Vernio aumenta fino al 1931 (probabilmente in relazione alla costruzione della grande galleria ferroviaria appenninica) sfiorando i 9.000 residenti; poi cala, stabilizzandosi a partire dal 1981. Il numero dei residenti è quasi sestuplicato (570,8%) nei 50 anni dal 1951 al 2001: è senza dubbio il comune toscano che ha avuto un più forte ritmo di crescita. L’insediamento urbano recente è cresciuto occupando il fondovalle anche con insediamenti produttivi, sebbene essi oggi non abbiano il radicamento territoriale di quelli storici rispetto alla disponibilità di acqua, cosicché sono frequenti gli squilibri di scala rispetto alle dimensioni della sezione del fondovalle (Vaiano). -

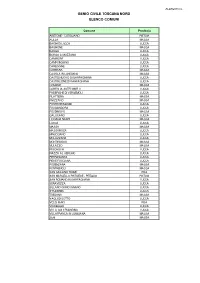

Allegato C Genio Civile Toscana Nord Elenco Comuni

ALLEGATO C GENIO CIVILE TOSCANA NORD ELENCO COMUNI Comune Provincia ABETONE - CUTIGLIANO PISTOIA AULLA MASSA BAGNI DI LUCCA LUCCA BAGNONE MASSA BARGA LUCCA BORGO A MOZZANO LUCCA CAMAIORE LUCCA CAMPORGIANO LUCCA CAREGGINE LUCCA CARRARA MASSA CASOLA IN LUNIGIANA MASSA CASTELNUOVO DI GARFAGNANA LUCCA CASTIGLIONE DI GARFAGNANA LUCCA COMANO MASSA COREGLIA ANTELMINELLI LUCCA FABBRICHE DI VERGEMOLI LUCCA FILATTIERA MASSA FIVIZZANO MASSA FORTE DEI MARMI LUCCA FOSCIANDORA LUCCA FOSDINOVO MASSA GALLICANO LUCCA LICCIANA NARDI MASSA LUCCA LUCCA MASSA MASSA MASSAROSA LUCCA MINUCCIANO LUCCA MOLAZZANA LUCCA MONTIGNOSO MASSA MULAZZO MASSA PESCAGLIA LUCCA PIAZZA AL SERCHIO LUCCA PIETRASANTA LUCCA PIEVE FOSCIANA LUCCA PODENZANA MASSA PONTREMOLI MASSA SAN GIULIANO TERME PISA SAN MARCELLO PISTOIESE - PITEGLIO PISTOIA SAN ROMANO IN GARFAGNANA LUCCA SERAVEZZA LUCCA SILLANO GIUNCUGNANO LUCCA STAZZEMA LUCCA TRESANA MASSA VAGLI DI SOTTO LUCCA VECCHIANO PISA VIAREGGIO LUCCA VILLA COLLEMANDINA LUCCA VILLAFRANCA IN LUNIGIANA MASSA ZERI MASSA ALLEGATO C GENIO CIVILE VALDARNO SUPERIORE ELENCO COMUNI Comune Provincia ANGHIARI AREZZO AREZZO AREZZO BADIA TEDALDA AREZZO BAGNO A RIPOLI FIRENZE BARBERINO DI MUGELLO FIRENZE BIBBIENA AREZZO BORGO SAN LORENZO FIRENZE BUCINE AREZZO CAPOLONA -CASTIGLION FIBOCCHI AREZZO CAPRESE MICHELANGELO AREZZO CASTEL FOCOGNANO AREZZO CASTEL SAN NICCOLO' AREZZO CASTELFRANCO - PIANDISCO' AREZZO CASTIGLION FIORENTINO AREZZO CAVRIGLIA AREZZO CHITIGNANO AREZZO CHIUSI DELLA VERNA AREZZO CIVITELLA IN VAL DI CHIANA AREZZO CORTONA AREZZO DICOMANO -

Sustainable Fashion in Italy

SUSTAINABLE FASHION IN ITALY Commissioned by the Netherlands Enterprise Agency SUSTAINABLE FASHION IN ITALY A GUIDE FOR DUTCH FASHION ENTREPRENEURS CONTENTS: 1 UN sustainable development goals and two words about sustainability 3 2 To identify the most sustainable fibers we must know them 5 Environmental consequences caused by the use of yarns 6 Global fibers production 1900>2017 + 2017 7 Cotton 8 Other natural vegetable fibers 11 Silk 12 Wool 14 Artificial fibers Viscose 16 Tencel 16 Syntethic fibers 17 3 How to build a sustainable brand 18 4 Italian sustainable lists 20 Italian textile producers 21 Top Italian sustainable brands 26 New Italian sustainable fashion designers 28 5 Italian exhibitions 29 Exhibiting in the Italian fairs 32 Visiting the Italian fairs 32 How fairs have included sustainability 32 Italian special fashion events 33 6 Roads to access the Italian market 34 7 Most important buyers 35 8 Conclusions 36 Contacts 38 2 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS GOAL 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere GOAL 2: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture 1GOAL 3: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages GOAL 4: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote life- long learning opportunities for all GOAL 5: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls GOAL 6: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all GOAL 7: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern en- ergy for all GOAL 8: Promote -

Italian Fashion & Innovation

Italian Fashion & Innovation Derek Pante Azmina Karimi Morgan Taylor Russell Taylor Introduction In Spring 2008, the Italia Design team researched the fashion industry in Italy, and discussed briefly how it fits into Italy’s overall innovation. The global public’s perception of Italy and Italian Design rests to some degree on the visibility and success of Fashion Design. The fashion and design industries account for a large percentage of Milan’s total economic output— as Milan goes economically, so goes Italy (Foot, 2001). Fashion Design clearly contributes to “brand Italia,” as well as to Italian culture generally. Yet, fashion is not our focus in this study: innovation and design is. Fashion’s goals are not the same as design. For one, fashion operates on “style,” design works on “language,” and style to a serious designer is usually the opposite of good design. Yet to ignore the area possibly creates a blind spot. With the resource this year of some students with great interest in this area it was decided that we should begin to investigate how fashion in Italy contributes to innovation, and how fashion in Milan and other centers in the North of Italy sustain “Creative Centers” where measurable agglomeration (a sign of innovation) occurs. Delving into Italian Fashion allowed us to rethink certain paradigms. For one, how we look at Florence as a design center. Florence has very little Industrial Design and, because of the city’s UNESCO World Heritage designation, has very little contemporary architectural culture. This reality became clear after four years of returning to the Renaissance city. -

Renaissance Receptions of Ovid's Tristia Dissertation

RENAISSANCE RECEPTIONS OF OVID’S TRISTIA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Gabriel Fuchs, M.A. Graduate Program in Greek and Latin The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Frank T. Coulson, Advisor Benjamin Acosta-Hughes Tom Hawkins Copyright by Gabriel Fuchs 2013 ABSTRACT This study examines two facets of the reception of Ovid’s Tristia in the 16th century: its commentary tradition and its adaptation by Latin poets. It lays the groundwork for a more comprehensive study of the Renaissance reception of the Tristia by providing a scholarly platform where there was none before (particularly with regard to the unedited, unpublished commentary tradition), and offers literary case studies of poetic postscripts to Ovid’s Tristia in order to explore the wider impact of Ovid’s exilic imaginary in 16th-century Europe. After a brief introduction, the second chapter introduces the three major commentaries on the Tristia printed in the Renaissance: those of Bartolomaeus Merula (published 1499, Venice), Veit Amerbach (1549, Basel), and Hecules Ciofanus (1581, Antwerp) and analyzes their various contexts, styles, and approaches to the text. The third chapter shows the commentators at work, presenting a more focused look at how these commentators apply their differing methods to the same selection of the Tristia, namely Book 2. These two chapters combine to demonstrate how commentary on the Tristia developed over the course of the 16th century: it begins from an encyclopedic approach, becomes focused on rhetoric, and is later aimed at textual criticism, presenting a trajectory that ii becomes increasingly focused and philological. -

Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci: Beauty. Politics, Literature and Art in Early Renaissance Florence

! ! ! ! ! ! ! SIMONETTA CATTANEO VESPUCCI: BEAUTY, POLITICS, LITERATURE AND ART IN EARLY RENAISSANCE FLORENCE ! by ! JUDITH RACHEL ALLAN ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Department of Modern Languages School of Languages, Cultures, Art History and Music College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT ! My thesis offers the first full exploration of the literature and art associated with the Genoese noblewoman Simonetta Cattaneo Vespucci (1453-1476). Simonetta has gone down in legend as a model of Sandro Botticelli, and most scholarly discussions of her significance are principally concerned with either proving or disproving this theory. My point of departure, rather, is the series of vernacular poems that were written about Simonetta just before and shortly after her early death. I use them to tell a new story, that of the transformation of the historical monna Simonetta into a cultural icon, a literary and visual construct who served the political, aesthetic and pecuniary agendas of her poets and artists. -

Giorgio Vasari at 500: an Homage

Giorgio Vasari at 500: An Homage Liana De Girolami Cheney iorgio Vasari (1511-74), Tuscan painter, architect, art collector and writer, is best known for his Le Vile de' piu eccellenti architetti, Gpittori e scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri (Lives if the Most Excellent Architects, Painters and Sculptors if Italy, from Cimabue to the present time).! This first volume published in 1550 was followed in 1568 by an enlarged edition illustrated with woodcuts of artists' portraits. 2 By virtue of this text, Vasari is known as "the first art historian" (Rud 1 and 11)3 since the time of Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historiae (Natural History, c. 79). It is almost impossible to imagine the history ofItalian art without Vasari, so fundamental is his Lives. It is the first real and autonomous history of art both because of its monumental scope and because of the integration of the individual biographies into a whole. According to his own account, Vasari, as a young man, was an apprentice to Andrea del Sarto, Rosso Fiorentino, and Baccio Bandinelli in Florence. Vasari's career is well documented, the fullest source of information being the autobiography or vita added to the 1568 edition of his Lives (Vasari, Vite, ed. Bettarini and Barocchi 369-413).4 Vasari had an extremely active artistic career, but much of his time was spent as an impresario devising decorations for courtly festivals and similar ephemera. He praised the Medici family for promoting his career from childhood, and much of his work was done for Cosimo I, Duke of Tuscany. -

Giorgio Vasari and Mannerist Architecture: a Marriage of Beauty and Function in Urban Spaces

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, October 2016, Vol. 6, No. 10, 1159-1180 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2016.10.007 D DAVID PUBLISHING Giorgio Vasari and Mannerist Architecture: A Marriage of Beauty and Function in Urban Spaces Liana De Girolami Cheney SIELAE, Universidad de Coruña, Coruña, Spain The first part of this essay deals with Giorgio Vasari’s conception of architecture in sixteenth-century Italy, and the second part examines Vasari’s practical application of one of his constructions, the loggia (open gallery or arcade) or corridoio (corridor). The essay also discusses the merits of Vasari’s open gallery (loggia) as a vernacular architectural construct with egalitarian functions and Vasari’s principles of architecture (design, rule, order, and proportion) and beauty (delight and necessity) for the formulation of the theory of art in Mannerism, a sixteenth-century style of art. Keywords: mannerism, fine arts, loggia (open gallery), architectural principles, theory of art, design, beauty, necessity and functionality Chi non ha disegno e grande invenzione da sé, sarà sempre povero di grazia, di perfezione e di giudizio ne’ componimenti grandi d’architettura. [One that lacks design and great invention [in his art] will always have meager architectural constructions lacking beauty, perfection, and judgment.] —Giorgio Vasari Vite (1550/1568)1 Introduction The renowned Mannerist painter, architect, and writer of Florence, Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574, see Figure 1), considered architecture one of the most important aspects of the fine arts or the sister arts (architecture, painting, and sculpture).2 In the first Florentine publication of the Vite with La Torrentina in 1550, Vasari’s original title lists architecture before the other arts: Le vite de più eccellenti architetti, pittori, et scultori Italiani da Cimabue insino a’ tempi nostri. -

The Historian Francesco Guicciardini Between Political Action and Historical Events*

The Historian Francesco Guicciardini * between Political Action and Historical Events IGOR MELANI The ambassadors sent abroad are the eyes and ears of republics, and it is they who should be believed, not those who have a personal stake in affairs.1 1. The Statesman Portrayed When composing his Dialogo della mutatione di Firenze (Dialogue on the Revol- ution in Florence) around the year 1520, Bartolomeo Cerretani set the scene in Modena, where Giovanni di Bernardo Rucellai, Florentine ambassador to the King of France and a »Pallesco« (partisan of the Medicean faction), encountered two Florentine gentlemen who were »Frateschi« (partisans of the Savonarolan faction). After their unexpected meeting abroad, the three fellow citizens, at the suggestion of Giovanni Rucellai, decide to spend the evening together at the house of the Governor (»a casa il Governatore«), who at that time was Francesco Guicciardini (»el quale era ms. Francesco Guicciardini«). The host had been absent from Florence (as ambassador to the King of Ara- gon) during the period of regime change in 1512, when the so-called »popular Government«, led by the Gonfaloniere-for-life Francesco Soderini, was over- turned and the Medici family restored. The dialogue is prompted by his request for news on this delicate topic, but with an eight-year delay: on recent political history, Cerretani’s Guicciardini seems far from up-to-date. In accordance with Rucellai’s wishes, the structure of the Dialogo is conceiv- ed as a sort of debate between two voices, integrating that of the Pallesco Rucellai himself on one side (giving an account of the »fall of the popular government«), _____________ * Primary sources in this expanded version of the paper presented at the conference Humanis- tische Geschichten am Hof have been translated into English by Patrick Baker except where otherwise noted.