The 9Th Speculative Fiction Contest Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

50 SECRETS Food Manufacturers Won’T Tell You an RD ORIGINAL

JUNE 2015 50 SECRETS Food Manufacturers Won’t Tell You An RD ORIGINAL ... 58 Boost Your Natural Genius FROM MASHABLE.COM ... 38 The World Is Not Falling Apart FROM SLATE.COM ... 106 David Sedaris Is Bit by the Fitbit FROM THE NEW YORKER ... 100 Cut Clutter Instantly FROM KEEP THIS, TOSS THAT ... 34 Marriage in 367 Words A LETTER BY RONALD REAGAN ... 36 The Man with Perfect Manners FROM MEDIUM.COM ... 31 Failure Is an Option BY J. K. ROWLING ... 20 The Most Stolen Social Security Number of All Time AN RD ORIGINAL ... 142 PLUS: Poetry Contest Winners FROM OUR READERS ... 128 Removable bookmark brought to you by Saving People Money Since 1936 ... that’s before there were TV Dinners. GEICO has been serving up great car insurance and fantastic customer service for more than 75 years. Get a quote and see how much you could save today. JHLFRFRP_$872_/RFDORIĆFH Some discounts, coverages, payment plans and features are not available in all states or all GEICO companies. GEICO is a registered service mark of Government Employees Insurance Company, Washington, D.C. 20076; a Berkshire Hathaway Inc. subsidiary. © 2015 GEICO Contents JUNE 2015 Cover Story Personal Essay 58 50 SECRETS FOOD 100 BIT BY THE FITBIT MANUFACTURERS David Sedaris falls funny victim WON’T TELL YOU to the latest fitness fad. Eye-opening insights into how FROM THE NEW YORKER your food is made and what you Global Affairs can do to eat better. 106 THE WORLD IS NOT MICHELLE CROUCH FALLING APART Drama in Real Life Poverty, crime, and violence 74 PRECIOUS are down. -

Radio Essentials 2012

Artist Song Series Issue Track 44 When Your Heart Stops BeatingHitz Radio Issue 81 14 112 Dance With Me Hitz Radio Issue 19 12 112 Peaches & Cream Hitz Radio Issue 13 11 311 Don't Tread On Me Hitz Radio Issue 64 8 311 Love Song Hitz Radio Issue 48 5 - Happy Birthday To You Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 21 - Wedding Processional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 22 - Wedding Recessional Radio Essential IssueSeries 40 Disc 40 23 10 Years Beautiful Hitz Radio Issue 99 6 10 Years Burnout Modern Rock RadioJul-18 10 10 Years Wasteland Hitz Radio Issue 68 4 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night Radio Essential IssueSeries 44 Disc 44 4 1975, The Chocolate Modern Rock RadioDec-13 12 1975, The Girls Mainstream RadioNov-14 8 1975, The Give Yourself A Try Modern Rock RadioSep-18 20 1975, The Love It If We Made It Modern Rock RadioJan-19 16 1975, The Love Me Modern Rock RadioJan-16 10 1975, The Sex Modern Rock RadioMar-14 18 1975, The Somebody Else Modern Rock RadioOct-16 21 1975, The The City Modern Rock RadioFeb-14 12 1975, The The Sound Modern Rock RadioJun-16 10 2 Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 4 2 Pistols She Got It Hitz Radio Issue 96 16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Radio Essential IssueSeries 23 Disc 23 3 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Radio Essential IssueSeries 22 Disc 22 16 21 Savage Feat. J. Cole a lot Mainstream RadioMay-19 11 3 Deep Can't Get Over You Hitz Radio Issue 16 6 3 Doors Down Away From The Sun Hitz Radio Issue 46 6 3 Doors Down Be Like That Hitz Radio Issue 16 2 3 Doors Down Behind Those Eyes Hitz Radio Issue 62 16 3 Doors Down Duck And Run Hitz Radio Issue 12 15 3 Doors Down Here Without You Hitz Radio Issue 41 14 3 Doors Down In The Dark Modern Rock RadioMar-16 10 3 Doors Down It's Not My Time Hitz Radio Issue 95 3 3 Doors Down Kryptonite Hitz Radio Issue 3 9 3 Doors Down Let Me Go Hitz Radio Issue 57 15 3 Doors Down One Light Modern Rock RadioJan-13 6 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone Hitz Radio Issue 31 2 3 Doors Down Feat. -

Bands Beers & Birds

ETHERIDGE LOCAL ROCK NEW ALBUM things to do AT THE CLYDE BY DORMANT BY LOVEWAR 329in the area CALENDARS START ON PAGE 10 Apr. 25-May 1, 2019 FREE WHAT THERE IS TO DO IN FORT WAYNE AND BEYOND BANDS BEERS & BIRDS SOL FEST FOX ISLAND OPENS FESTIVAL SEASON ALSO INSIDE: DENNIS DEYOUNG · CLASSIC DEEP PURPLE · LOCAL THEATER COVERAGE · MUSIC AND MOVIES whatzup.com ClydeClubRoom.com | (260) 407-8530 1806 Bluffton Road, Fort Wayne, IN 46809 NEW! SUNDAY SESSIONS SEATING TIMES: SWEETWATER MAY 05 10AM & 11:30AM ALL STARS Come celebrate the first-ever Sunday Brunch Session at The Club Room. Your brunch reservation starts with an incredible meal, with choices ranging from yogurt, muffins, or bagels to breakfast burritos, chicken and waffles, avocado toast, and more. A fantastic list of brunch-approved cocktails is also available, and after the meal, you’ll enjoy a performance by the Sweetwater All Stars, Northeast Indiana’s premier rhythm & blues band. 3-course meal | $28 per person Call to make a reservation (recommended). Inside This Week Volume 23, Number 39 Dormant Dennis4 5 DeYoung Sol 7Fest Old Dominion9 Classic6 Deep Purple Columns & Reviews Calendars Feature: Buckethead ⁄ 8 Spins ⁄ 20-21 On the Road ⁄ 10-12 Secret recipe under bucket of brilliant Lovewar, Tamaryn, George Strait, multi-instrumentalist Altitudes + Attitudes Road Trips ⁄ 11 Road Notes ⁄ 10 Backtracks ⁄ 20 Live Music & Comedy ⁄ 15-19 Get in line for Last in Line at the Diesel, Watts in a Tank (1981) Stage & Dance ⁄ 24 Honeywell LONGE Reel Views ⁄ 22 Things To Do ⁄ 26 Out and About -

Come to Jesus

COME TO JESUS by Newman Hall (1816-1902) Contents 1. Come to Jesus...........................................................................................3 2. Why should I come? .............................................................................4 3. Who is Jesus?....................................................................................... 10 4. Where is Jesus?.................................................................................... 15 5. What is meant by “coming to Jesus”?.................................................. 15 6. Who should come?............................................................................. 22 7. Why should you come now? ............................................................ 26 Come to Jesus was originally published in the 1800s by the Evangelical Tract Society (No. 110), Petersburg, Virginia. Text is provided courtesy of Documenting the American South, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Libraries. © Copyright 2013 Chapel Library: annotations. Printed in the USA. Permission is expressly granted to reproduce this material by any means, provided 1. you do not charge beyond a nominal sum for cost of duplication; 2. this copyright notice and all the text on this page are included. Chapel Library is a faith ministry that relies entirely upon God’s faithfulness. We therefore do not solicit donations, but we gratefully receive support from those who freely desire to give. Chapel Library does not necessarily agree with all the doctrinal positions of the authors -

Ecological Models of Musical Structure in Pop-Rock, 1950–2019

Ecological Models of Musical Structure in Pop-rock, 1950–2019 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Nicholas J. Shea, M.A., B.Ed. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 Dissertation Committee: Anna Gawboy, Advisor and Dissertation Co-Advisor Nicole Biamonte, Dissertation Co-Advisor Daniel Shanahan David Clampitt Copyright by Nicholas J. Shea 2020 Abstract This dissertation explores the relationship between guitar performance and the functional components of musical organization in popular-music songs from 1954 to 2019. Under an ecological theory of affordances, three distinct interdisciplinary approaches are employed: empirical analyses of two stylistically contrasting databases of popular-music song transcriptions, a motion-capture study of performances by practicing musicians local to Columbus, Ohio, and close readings of works performed and/or composed by popular- music guitarists. Each offers gestural analyses that provide an alternative to the object- oriented approach of standard popular-music analysis, as well as clarification on issues related to style, such as the socially determined differences between “pop” and “rock” music. ii Dedication To Anna Gawboy, who is always in my corner. iii Acknowledgments Here I face the nearly insurmountable task of thanking those who have helped to develop this research. Even as all written and analytical content in this document is my own, I cannot deny the incredible value collaboration has brought to this inherently interdisciplinary study. I am extremely fortunate to have a small team of individuals on which I can rely for mentorship and support and whose research backgrounds contribute greatly to the domains of this document. -

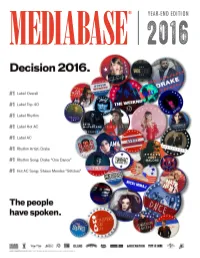

Year-End Edition 2016

® YEAR-END EDITION 2 01 6 REPUBLIC #1 FOR THIRD STRAIGHT YEAR RCA Runner Up; Columbia Moves 5-3; Def Jam, 9-4; Interscope 5th REPUBLIC continues its reign as the #1 overall label in Mediabase chart share for a third straight year. The 2016 chart year is based on the time period from November 15, 2015 through November 12, 2016. Of the 10 Mediabase formats that comprise overall rankings, Republic landed the #1 spot at four formats: Top 40, Rhythmic, Hot AC and AC. Republic had a total chart share of 17.9%, while scoring over a 20% share at Top 40 (23.7%), Rhythmic (20.2%), and AC (20.2%). OTHER HIGHLIGHTS FOR REPUBLIC THIS YEAR: - The label’s total spins for the year across all formats was 7,539,293 – the second highest total ever – only behind the 9.3 million they had in their record setting 2015. - Over half of the Republic spins came at the Top 40 format, where they scored 3,834,134, over 1.6 million spins ahead of the next closest competitor. - Republic had 1,119,628 spins at Rhythmic and 1,117,379 at Hot AC, with both of those joining the million spin club. - For the second consecutive year, Republic nabbed the top slot honors at Top 40, Rhythmic and AC. - Republic was #3 Urban, #5 at Active Rock, #6 at Urban AC , #7 at Alternative, and #8 at Triple A. - Four of the top 10 artists at Top 40 belonged to Republic with Drake (#4), The Weeknd (#7), Shawn Mendes (#8), and Ariana Grande (#9). -

2015Addendumcatalog.Pdf

2 CONTENTS Popular Piano Collections ................. 4 Band Instruments ...................... 32 Sheet Music ............................. 7 String Instruments. .34 Guitar .................................. 8 Vocal & Choral .......................... 35 Bass Guitar ............................ 13 Classroom ............................. 36 Daisy Rock Girl Guitars ................... 14 Sacred ................................. 38 Folk Instruments ....................... 15 Reference & Trade Books ................. 40 Piano Methods ......................... 17 Software .............................. 42 Supplementary Piano ................... 19 Masterworks ........................... 43 Holiday Music .......................... 22 Concert Band Performance Music ......... 44 Piano Masterworks ..................... 23 Orchestra Performance Music ............ 47 Drums & Percussion ..................... 25 Jazz Ensemble Performance Music ........ 49 Pro Audio .............................. 27 Marching Band Performance Music ........ 51 Essentials .............................. 28 Choral Octavos. .52 DVDs .................................. 29 Handbell .............................. 56 Pop Instrumental Series ................. 31 All prices in US$. Some titles are not available in all countries due to copyright restrictions. Prices and availability subject to change without notice. GERSHWIN®, GEORGE GERSHWIN® and IRA GERSHWIN™ are trademarks of Gershwin Enterprises. All rights reserved. For a full list of current titles, visit alfred.com. For -

Spring/Fall 2018 Vol

A PUBLICATION OF THE FOREST HISTORY SOCIETY SPRING/FALL 2018 VOL. 24, NOS. 1 & 2 MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Now We Begin STEVEN ANDERSON y the time this issue is published, the In our new building, we can begin afresh staff of the Forest History Society will to collect, preserve, and share forest history. Bhave finished moving into our new The Society is now reviewing our strategic library, archives, and headquarters. Our relo- initiatives to ensure that our programs take cation marks the accomplishment of the full advantage of the new space. We will Society’s highest strategic priority as set by its seek input from leaders, staff, and members, board of directors in 2010. It is the result of as well as those outside the organization, to excellent dynamics and collaboration between determine the highest priorities for future staff, the board, and our fundraising advisers, efforts and strengthen our ability to accom- moss+ross, LLC, which helped keep us on plish them. point and avoid the pitfalls of many capital One immediate priority will be to help campaigns. companies, organizations, and individuals The building itself is a beautiful and invit- make maximum use of the expanded space ing structure. Our site planner, Coulter, in the Alvin J. Huss Archives, one of the main Jewell, Thames, Inc., and our architect, DTW reasons for the new building. The new build- Architects & Planners, Inc., began assisting ing has about 7,500 linear feet—almost one- us as soon as we started to evaluate options and-a-half miles of archival storage—half of for new space. -

Download Book Seether -- Isolate and Medicate: Authentic Guitar

ODHWB10OGYMI // PDF \ Seether -- Isolate and Medicate: Authentic Guitar Tab Seeth er -- Isolate and Medicate: A uth entic Guitar Tab Filesize: 2.31 MB Reviews Complete guideline for pdf fanatics. I could possibly comprehended everything out of this created e pdf. You can expect to like just how the writer compose this pdf. (Nya Kunde) DISCLAIMER | DMCA GPD4SRBH8VIH > PDF > Seether -- Isolate and Medicate: Authentic Guitar Tab SEETHER -- ISOLATE AND MEDICATE: AUTHENTIC GUITAR TAB To get Seether -- Isolate and Medicate: Authentic Guitar Tab PDF, make sure you follow the web link below and download the file or get access to other information which are related to SEETHER -- ISOLATE AND MEDICATE: AUTHENTIC GUITAR TAB ebook. Alfred Publishing Co., Inc., United States, 2014. Paperback. Book Condition: New. 300 x 226 mm. Language: English . Brand New Book. Seether comes out sounding truly seasoned on Isolate and Medicate, their sixth studio album. This album-matching folio contains guitar TAB transcriptions of all the songs on the record, including the four bonus songs featured on the deluxe edition. Titles: See You at the Bottom * Same Damn Life * Words as Weapons * My Disaster * Crash * Suer It All * Watch Me Drown * Nobody Praying for Me * Keep the Dogs at Bay * Save Today * Turn Around * Burn the World * Goodbye Tonight * Weak. Read Seether -- Isolate and Medicate: Authentic Guitar Tab Online Download PDF Seether -- Isolate and Medicate: Authentic Guitar Tab Download ePUB Seether -- Isolate and Medicate: Authentic Guitar Tab UIANFQSI0MYA ^ Kindle ~ Seether -- Isolate and Medicate: Authentic Guitar Tab Oth er eBooks [PDF] Found around the world : pay attention to safety(Chinese Edition) Access the link under to download and read "Found around the world : pay attention to safety(Chinese Edition)" file. -

Praise & Worship

page 44 page 44 Spring/SummerMUSIC 2014 More Than 20,000 CDs and 174,000 Music Downloads Available at Christianbook.com! page 6 Christianbook.com 1–800–CHRISTIAN® New Release ALL SONS & DAUGHTERS Table of Contents Ex pe ri ence God right where you are as you Accompaniment Tracks . .16, 17 listen to the soul-baring Bargains . .42 songs of All Sons & Daughters! Connect with Collections . .4, 6–8, 11, 13–15, 20, 21, the power of praise & 24–29, 36, 37, 39–42 worship in “More Than Contemporary & Pop . .30–33 Anything”; “Christ Be All Around”; “We Give You Folios & Songbooks . .18, 19 Thanks”; “You Will Re - Gifts . .back cover main”; “Almighty God”; Hymns . .26–29 “Your Glory & My Good”; “Great Are You, Lord”; and more. $ 99 Inspirational . .24, 25 UECD64820 Retail $13.99 . .CBD Price 11 Instrumental . .14, 15 Kids’ Music . .20, 21 Messianic . .12, 13 ans of music—rejoice! We’re always bringing New Releases . .2–7 tian music has to offer Fyou the best that Chris Order Form . .22, 23 and this catalog is no exception. Praise & Worship . .8–11, back cover If you’re looking for something soul-soothing, Rock & Alternative . .34, 35 check out the best-selling worship music on pages Scenic Music DVDs . .40, 41 8–11 or browse inspirational tunes on pages 24 & 25. For contemporary and pop favorites, see pages Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass . .36–39 30–33; or turn to pages 34 & 35 for music that WOW . .43, back cover rocks. And don’t miss best-selling CDs from your favorite artists for only $5 on page 42! Search our entire music inventory by artist, Shop 24 hours a day; select from more than title, or topic at Christianbook.com! 20,000 CDs and 174,000 music downloads; listen- to samples; browse your favorite artists’ full back lists; check out new releases; and order securely online—all at Christianbook.com. -

DREAM out LOUD a Documentary Journey a Subterranean Odyssey Don Alex Subterranean Cinema 2017 My Name Is Don Alex

DREAM OUT LOUD A Documentary Journey A Subterranean Odyssey Don Alex Subterranean Cinema 2017 My name is Don Alex. I am a 53 year old man, with a very charismatic and lovable 13 year old Black Lab named Mitzi. I am best known as the creator of a website called "Subterranean Cinema" that I first published in early 2001, which gained a solid worldwide reputation for making several rare screenplays available to the general public for the very first time, including two different drafts of Jerry Lewis' "The Day the Clown Cried", John Belushi's "Noble Rot", Andy Kaufman's "The Tony Clifton Story", and Rospo Pallenberg's unproduced adaption of Stephen King's "The Stand". I also created a tribute documentary called "The Passion of Andy Kaufman" which has a substantial cult following among his fans on the internet, and several "short films" based upon the music of Richard Patrick (Filter, Army of Anyone, Nine Inch Nails), which he artistically admired to such an extent that I am now given "VIP" status at Filter concerts that I attend. His music has literally changed the path of my life. Mitzi was my mom's last dog. In my final phone conversation with her just before her death in 2011, she asked me to keep Mitzi with me no matter what, that she would "open doors" for me. I promised her that I would, and I have gone through several very difficult years since then, through times that would have been much easier if I had put Mitzi up for adoption, but I have kept my word, and Mitzi has indeed "opened doors" and enriched my life with her presence in it. -

8 ” U. N. Planes, Big Guns Blast Reds Blocking Escape for 20,000 GI's

FRIDAT, DECEMBER S. IMO t - A vm go Dtily Net PrcM Ran ifettfligBter gt[gnte0 ijgratt rqr tbs Weak BMing PsNssM y o o[*wSaSMt ■ Desenbert, ISN Tadsy partly ctoady wMh eat tewperstwre m m b - 10,163 geaeraRy fair with tawnat' SHOP HALE'S FOft YOUR Mstber of tbs Audit ^ atara aear SSt Saadi ■w an e( dreolathms AfancJkeEfor—-t4 City o / Filloifo Charm Qift '/a VOL. LXX, NO. S9 AdvsrtMag oa rags 1Z> MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, DECEMBER ». 1950 (FOURTEEN PAGES) PRICE POOR C B im Big Transport Professor Tests Honesty Policeman Killed, Woman H eld^ Shooting Big Thrpe Will HOSIERY 0 * ^ . Of Class and—Surprise! Alba 51 GauQa Shaar... .$1.50 pr. U. N. Planes, Big Guns On Korea Duty Los Angeles, Dec. 9.—(/Tt— Meet Russians Alba Dark Saam Shaar. $ 1.65 pr. The students in Dr. Richard F. Van Raalta Sami Shaar . .$1.50 pr. Reath’s classes at Occidental Is Sabotaged College, may not all be bril 111 World Talk G ift HANDKERCHIEFS No'Mand Shaar Nylon . $ 1.95 pr. liant, but they’re honest. No'Mand Sami Shaar .... $ 1.65 pr. Dr. Reath, a political science Blast Reds Blocking Bquar. or Round hanVlei Jn all whlU or prlnta. 10 professor, lost his grade book Budgat Shaar Nylon........ $ 1.25 pr. Vessel Damaged in 5 a week ago. Convinced it was Offer to Discuss All Llnan or flne quality cotton. Wool Anklati .. .79c and $1.00 pr. Different Places at gone for good, he asked the 63 Global Problems In students in his classes to write Marearizad Cotton Seattle D ock; Press down for his records the cluding Europe, Korea to sl.OO Anklatt......V.