Narrating the Berlin Wall: Nostalgia and the Negotiation of Memory, 20 Years Later

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Humor Und Kritik in Erzählungen Über Den Alltag in Der DDR. Eine Analyse Am Beispiel Von Am Kürzeren Ende Der Sonnenallee Und in Zeiten Des Abnehmenden Lichts

UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA FACULTAD DE FILOLOGÍA GRADO EN ESTUDIOS ALEMANES Trabajo de Fin de Grado Humor und Kritik in Erzählungen über den Alltag in der DDR. Eine Analyse am Beispiel von Am kürzeren Ende der Sonnenallee und In Zeiten des abnehmenden Lichts. David Jiménez Urbán Prof. Dr. Patricia Cifre Wibrow Salamanca, 2018 Danksagung Ich danke meiner Mutter für die Unterstützung und meinem Vater (in memoriam) für das Vertrauen. Ich danke Prof. Dr. Patricia Cifre für ihre Leidenschaft für die Literatur. Ich danke den wunderbaren Menschen, die Salamanca in mein Leben gebracht hat, für die reichen Erinnerungen. David Jiménez Urbán Salamanca, 21.06.2018 2 Inhaltverzeichnis 1. Einleitung .................................................................................................................. 4 2. (N)Ostalgie und Humor ............................................................................................. 5 3. Am kürzeren Ende der Sonnenallee: schlechtes Gedächtnis und reiche Erinnerungen .................................................................................................................... 8 4. In Zeiten des abnehmenden Lichts: Verfall einer kommunistischen Familie ......... 12 5. Schlussfolgerungen. ................................................................................................ 15 6. Literaturverzeichnis ................................................................................................. 17 3 1. Einleitung In der Nacht vom Donnerstag, dem 9. November, auf Freitag, den 10. November -

Wallmaps.Pdf

S Prenzlauer Allee U Volta Straße U Eberswalder Straße 1 S Greifswalder Straße U Bernauer Straße U Schwartzkopff Straße U Senefelderplatz S Nordbanhof Zinnowitzer U Straße U Rosenthaler Plaz U Rosa-Luxembury-Platz Berlin HBF DB Oranienburger U U Weinmeister Straße Tor S Oranienburger S Hauptbahnhof Straße S Alexander Platz Hackescher Markt U 2 S Alexander Plaz Friedrich Straße S U Schilling Straße U Friedrich Straße U Weberwiese U Kloster Straße S Unter den Linden Strausberger Platz U U Jannowitzbrucke U Franzosische Straße Frankfurter U Jannowitzbrucke S Tor 3 4 U Hausvogtei Platz U Markisches Museum Mohren Straße U U Spittelmarkt U Stadtmitte U Heirch-Heine-Straße S Ostbahnhof Potsdamer Platz S U Potsdamer Platz 5 S U Koch Straße Warschauer Straße Anhalter Bahnhof U SS Moritzplatz U Warschauer Mendelssohn- U Straße Bartholdy-Park U Kottbusser Schlesisches Tor U U Mockernbrucke U Gorlitzer U Prinzen Straße Tor U Gleisdreieck U Hallesches Tor Bahnhof U Mehringdamm 400 METRES Berlin wall - - - U Schonlein Straße Download five Eyewitnesses describe Stasi file and discover Maps and video podtours Guardian Berlin Wall what it was like to wake the plans had been films from iTunes to up to a divided city, with made for her life. Many 1. Bernauer Strasse Construction and escapes take with you to the the wall slicing through put their lives at risk city to use as audio- their lives, cutting them trying to oppose the 2. Brandenburg gate visual guides on your off from family and regime. Plus Guardian Life on both sides of the iPod or mp3 player. friends. -

Gerhard Wettig Chruschtschows Berlin-Krise 1958 Bis 1963 II Quellen Und Darstellungen Zur Zeitgeschichte Herausgegeben Vom Institut Für Zeitgeschichte Band 67

I Gerhard Wettig Chruschtschows Berlin-Krise 1958 bis 1963 II Quellen und Darstellungen zur Zeitgeschichte Herausgegeben vom Institut für Zeitgeschichte Band 67 R. Oldenbourg Verlag München 2006 III Gerhard Wettig Chruschtschows Berlin-Krise 1958 bis 1963 Drohpolitik und Mauerbau R. Oldenbourg Verlag München 2006 IV Unterstützt durch die gemeinsame Kommission für die Erforschung der jüngeren Geschichte der deutsch-russischen Beziehungen, gefördert aus Mitteln des Bundesministeriums des Innern. Bibliografische Information Der Deutschen Bibliothek Die Deutsche Bibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.ddb.de> abrufbar. © 2006 Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag GmbH, München Rosenheimer Straße 145, D-81671 München Internet: oldenbourg.de Das Werk einschließlich aller Abbildungen ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages unzu- lässig und strafbar. Dies gilt insbesondere für die Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikro- verfilmungen und die Einspeicherung und Bearbeitung in elektronischen Systemen. Umschlaggestaltung: Dieter Vollendorf Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, alterungsbeständigem Papier (chlorfrei gebleicht). Gesamtherstellung: R. Oldenbourg Graphische Betriebe Druckerei GmbH, München ISBN-13: 978-3-486-57993-2 ISBN-10: 3-486-57993-2 Inhalt V Inhalt Vorwort....................................................... IX 1. Einleitung. 1 Themenstellung . 2 Quellenlage . 3 2. Vorgeschichte. 7 Latenter Konflikt mit der DDR über deren Souveränitätsbefugnisse . 7 Wachsende Aufgeschlossenheit gegenüber Vorstellungen der DDR . 9 Eingehen auf die innenpolitische Nöte der SED-Führung . 12 Sich anbahnender Kurswechsel . 14 Entschluß zum Vorgehen gegen West-Berlin . 16 Überlegungen und Beratungen im Sommer 1958. 18 Aufforderung zum Abschluß eines Friedensvertrages. 20 Vorbereitungen für die politische Offensive gegen West-Berlin. 22 Steigerung bis zur Ablehnung der Vier-Mächte-Rechte insgesamt . -

THIERRY NOIR Howard Griffin Gallery Los Angeles October 2014 to December 2014

THE LA RETROSPECTIVE: THIERRY NOIR Howard Griffin Gallery Los Angeles October 2014 to December 2014 From 11th October 2014, Howard Griffin Gallery Los Angeles presents a retrospective of the life and work of infamous Berlin Wall artist Thierry Noir. In 1984, Noir was the first artist to illegally paint mile upon mile of the Berlin Wall. Noir wanted to perform one real revolutionary act: to paint the Wall, to transform it, to make it ridiculous, and ultimately to help destroy it. Noir’s iconic, bright and seemingly innocent works painted on this deadly border symbolised a sole act of defiance and a lone voice of freedom. In this landmark exhibition for Howard Griffin Gallery in Los Angeles, the artist’s first US solo exhibition, original works will be exhibited alongside rarely seen photographs, interviews and films, juxtaposing old and new to reassess Noir’s enduring legacy and contribution to society. The event also marks another first as the inaugural Los Angeles exhibition for Howard Griffin Gallery. A number of artists, musicians and free thinkers settled in West Berlin during the 1980s despite the difficulties of the time. Within a group which included David Bowie and Iggy Pop, was a rebellious young French artist called Thierry Noir. Thierry Noir was born in 1958 in and his monsters are a metaphor for the wall itself, Lyon, France and moved to Berlin in 1982 with one each one relating to his experiences or feelings of what suitcase. By chance he settled in a squat overlooking the he calls a ‘killing machine’. His enormous murals in Wall at the border of East and West Berlin. -

Berlin Wall's Most Iconic Paintings Under Threat

News-based English language activities from the global newspaper Page 1 March 2013 Level ≥ Advanced These worksheets can be downloaded free from guardian.co.uk/weekly. You can also find more advice for teachers and learners from the Guardian Weekly’s Learning English section on the site. Materials prepared by Janet Hardy-Gould Berlin Wall’s most iconic paintings under threat Berlin Wall murals by the French artist Thierry Noir who has joined protests to save the wall Action Press/Rex 5 What was the open section of land between Before reading the east and west side of the wall known as? 1 Look at the photos of the Berlin Wall on page 5. a The iron curtain b The death strip What do you know about the history of the wall? c The Eastern Bloc d Checkpoint Charlie Work in pairs and answer the questions below. 6 When was the wall finally opened and partly 1 When was the Berlin Wall built? knocked down? a 1947 b 1955 c 1961 d 1966 a 1983 b 1987 c 1989 d 1992 2 How long was the wall in its final version? a 53km b 89km c 104km d 155km 2 Look again at the photos A-C of the Berlin Wall. 3 How many people are believed to have How could you describe the current artwork on escaped across the wall? the wall? Tick the appropriate adjectives. a Nearly 100 b About 350 c Around 1,500 anarchic colourful conservative d Approximately 5,000 conventional monochrome orthodox 4 Which US president visited Berlin after the political radical revolutionary wall was built and said: “Ich bin ein Berliner.”? subversive thought-provoking traditional a Kennedy b Roosevelt c Truman unadventurous d Eisenhower ≥2 News-based English language activities from the global newspaper Page 2 March 2013 3 Look at these words from the article about structure was now under threat. -

Überseehafen Rostock: East Germany’S Window to the World Under Stasi Watch, 1961-1989

Tomasz Blusiewicz Überseehafen Rostock: East Germany’s Window to the World under Stasi Watch, 1961-1989 Draft: Please do not cite Dear colleagues, Thank you for your interest in my dissertation chapter. Please see my dissertation outline to get a sense of how it is going to fit within the larger project, which also includes Poland and the Soviet Union, if you're curious. This is of course early work in progress. I apologize in advance for the chapter's messy character, sloppy editing, typos, errors, provisional footnotes, etc,. Still, I hope I've managed to reanimate my prose to an edible condition. I am looking forward to hearing your thoughts. Tomasz I. Introduction Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski, a Stasi Oberst in besonderen Einsatz , a colonel in special capacity, passed away on June 21, 2015. He was 83 years old. Schalck -- as he was usually called by his subordinates -- spent most of the last quarter-century in an insulated Bavarian mountain retreat, his career being all over three weeks after the fall of the Wall. But his death did not pass unnoticed. All major German evening TV news services marked his death, most with a few minutes of extended commentary. The most popular one, Tagesschau , painted a picture of his life in colors appropriately dark for one of the most influential and enigmatic figures of the Honecker regime. True, Mielke or Honecker usually had the last word, yet Schalck's aura of power appears unparalleled precisely because the strings he pulled remained almost always behind the scenes. "One never saw his face at the time. -

Recent Literature Various Authors

GDR Bulletin Volume 16 Issue 2 Fall Article 25 1990 Recent Literature various authors Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/gdr This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 License. Recommended Citation authors, various (1990) "Recent Literature," GDR Bulletin: Vol. 16: Iss. 2. https://doi.org/10.4148/ gdrb.v16i2.982 This Announcement is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in GDR Bulletin by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. authors: Recent Literature tagung mit den Themen "Literatur und Gesellschaft in beiden ihren gut informierten und einsichtsvollen Antworten zu Fragen deutschen Staaten" oder "Literatur und Theater" an der Euro• aus verschiedensten Gebieten—vom schweren Weg zur freien päischen Akademie Berlin statt. Eingeführt wurde dieses Marktwirtschaft nach ökonomischem Bankrott bis zur neuen Si• Seminar von Frau Professor Ursula Beitter, Germanistin am tuation der Frau in der DDR. Loyola College. Maryland, die bisher zusammen mit dem Leiter Günter de Bruyn (1920 geb.), Schriftsteller in Berlin/DDR, der Europäischen Akademie Richard Dahlheim die Programme sprach zum Thema "Parteilichkeit ohne Partei—Schriftsteller und mit Schriftstellern. Liedermachern. Kritikern. Theater• Gesellschaft in der DDR." Zunächst las er aus seinem kürzlich direcktoren usw. aus Ost und West plante. veröffentlichten Aufsatz in Sinn und Form, "Zur Erinnerung. Erich Loest leitete das Programm der Woche mit einer Lesung Brief an all, die es angeht." Ihm geht es vor allem um "Partei- und anschließendem Gespräch zum Thema "Schriftsteller in Nehmen" für Menschlichkeit und Wahrheit. -

Der Gefährliche Weg in Die Freiheit Fluchtversuche Aus Dem Ehemaligen Bezirk Potsdam

Eine Publikation der Brandenburgischen Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Hannelore Strehlow Der gefährliche Weg in die Freiheit Fluchtversuche aus dem ehemaligen Bezirk Potsdam Brandenburgische Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Die Bundesbeauftragte für die Unterlagen des Staatssicherheitsdienstes der ehemaligen DDR Außenstelle Potsdam Inhalt Vorwort 6 Kapitel 3 Fluchtversuche mit Todesfolge Quelleneditorische Hinweise 7 Fluchtversuch vom 22.11.1980 42 Kapitel 1 Ortslage Hohen-Neuendorf/Kreis Die Bezirksverwaltung Oranienburg der Staatssicherheit in Potsdam 8 Fluchtversuch vom 12.2.1987 52 Kapitel 2 im Bereich der Grenzübergangsstelle (GÜST) Der 13. August 1961 Rudower Chaussee – Mauerbau – 20 Fluchtversuch vom 7.2.1966 56 bei Staaken Quellenverzeichnis Kapitel 1 und 2 40 Fluchtversuch vom 14.4.1981 60 Bereich Teltow-Sigridshorst Quellenverzeichnis Kapitel 3 66 4 Kapitel 4 Kapitel 5 Gelungene Fluchtversuche Verhinderte Fluchtversuche durch Festnahmen Flucht vom 11.3.1988 68 über die Glienicker Brücke Festnahme vom 4.3.1975 102 an der GÜST/Drewitz Flucht vom 19.9.1985 76 im Grenzbereich der Havel Festnahme vom 27.10.1984 110 in der Nähe der GÜST/Nedlitz Flucht vom 4.1.1989 84 im Raum Klein-Ziethen/Kreis Festnahme vom 8.7.1988 114 Zossen in einer Wohnung im Kreis Kyritz 90 Flucht vom 26.7.73 Festnahme vom 8.6.1975 120 von 9 Personen durch einen Tunnel unter Schusswaffenanwendung im Raum Klein Glienicke an der GÜST/Drewitz Quellenverzeichnis Kapitel 4 101 Quellenverzeichnis Kapitel 5 128 Dokumententeil 129 Die Autorin 190 Impressum 191 5 Vorwort Froh und glücklich können wir heute sein, dass die Mauer, die die Menschen aus dem Osten Deutschlands jahrzehntelang von der westlichen Welt trennte, nicht mehr steht. -

Rammstein - Rosenrot Nur Ein Jahr Nach Dem Release Von „Reise,Reise“ Haben Rammstein Den Nächsten Longplayer Auf Den Markt Geworfen

Rammstein - Rosenrot Nur ein Jahr nach dem Release von „Reise,Reise“ haben Rammstein den nächsten Longplayer auf den Markt geworfen. Und wer jetzt denkt, na, da haben wir gewiß nur einen Schnellschuß zum schnellen Kohle machen veröffentlicht,wird sich nach dem Hören dieser CD eines besseren belehren lassen müssen. Rammstein - Rosenrot 1.Benzin 2.Mann gegen Mann 3.Rosenrot 4.Spring 5.Wo bist du 6.Stirb nicht vor mir // Dont Die Before I Do Feat. Sharleen Spiteri 7.Zerstören 8.Hilf mir 9.Te Quiero Puta! 10.Feuer und Wasser 11.Ein Lied Universal (Universal) Till Lindemann – Gesang Paul Landers – Gitarre Richard Kruspe Bernstein – Gitarre Christoph Schneider – Schlagzeug Oliver Riedel – Bass Christian "Flake" Lorenz – Keyboard Nur ein Jahr nach dem Release von „Reise,Reise“ haben Rammstein den nächsten Longplayer auf den Markt geworfen. Und wer jetzt denkt, na, da haben wir gewiß nur einen Schnellschuß zum schnellen Kohle machen veröffentlicht,wird sich nach dem Hören dieser CD eines besseren belehren lassen müssen. Denn textlich so gut wie hier, haben sich „Rammstein“ seit „Sehnsucht“ nicht mehr geäußert. Das beginnt mit „Spring“, einem der grandiosesten Texte, den die Band jemals geschrieben hat und wird nur noch von „Mann gegen Mann“ übertroffen, einem Text über Homosexualität, die durchaus die Chance hat, in den Schwulendiscos dieses Landes zur neuen Hymne zu avancieren. Der Text ist sehr tiefsinnig und wirkt in keinster Weise diskriminierend. Ich glaube, es hat sich in keiner Form jemals ein heterosexueller mann künstlerisch so poitiv über dieses Thema geäußert. Respekt. 1/2 Doch auch Knaller wie „Zestören“, ein Song über Gewalt gegen Gegenstände „Stirb nicht vor mir“, ein wunderschönes Liebeslied, oder „Rosenrot“ wissen mehr als nur zu gefallen. -

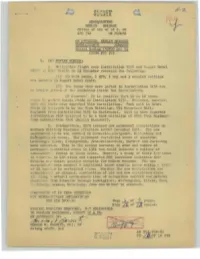

ISUM #3, Per10d Ending 142400 Dec 61

, 6-2.. • S'=I'R..."'~ ET. HEAIlQUARTElIS BERLIN BRIGADE Off ice of the AC of 8, G2 APO 742 US FOR::ES + 1 . (8 \ ~!l..'ClE1' FORCES: a. Hf'llccpter f light over Installation 4154 and AUf,J'1..lst Bebel PIa t."':t.:1 E.l.f"t Ber::'ln on 13 December revealed the following: (1) 29 T-S4 tanks , 1 BTR ~ 1 bus and 3 wheeled vehicles are lonat;u 1n August Ecbel Platz. (2) Tho tanks that were parked 1n Installation 4154 are n':) 10n3C'r jX.rkC'd oJ!" th::! hardstand inside the in::>tall at:'..on . 02 C:nlr.l.Cnt: It 1s possible thf'.t 10 to 12 tunI.s w'uld b,- p~.~'·:(r0. inside ::::h3ds 1n Insullatlon 415 1~ . Br;1 l.icved, ho~·e"E.r, thE'.t fO.ll tt.rks h'we dep.-,rtcd this installation. Tank unit in Bebel Platz 1s b_'1.i8ved to be Jchc Tt..nk Battalion, 83d Motorized Riflo il0giment fr.i:n Installation 4161 1n Karlshorst. Un! t to have departed IlStnllatl~n 4154 believe d to be a tank battalion of 68th Tnnk Regiment f rom InstallE:.tion 4102 (Berl~n Blesdorf). b . Headquarters, GSfo'G imposed new permanent 1'cstrictions on Wcs.tern Mili t:-", ry Missions effective 12000:1. December 1961. The new restrictcd c.r .m,s are located in Schwerin-~udwiglust, W:Ltt.3nburg and Ko·~igsb ru ,ck areas. The permanent r es tric ted areas of Guestrow; Letzlingcr lI~ide . Altengrabow. Jena-Weissenfe1s, Ohrdrv.f and Juetcl'bog were exten,Ld. -

Katalog FR En Web.Pdf

» WE ARE THE PEOPLE! « EXHIBITION MAGAZINE PEACEFUL REVOLUTION 1989/90 Published as part of the theme year “20 Years since the Fall of the Wall” by Kulturprojekte Berlin GmbH CONTENTS 7 | OPENING ADDRESS | KLAUS WOWEREIT 8 | OPENING ADDRESS | BERND NEUMANN 10 | 28 YEARS OF THE WALL 100 | TIMELINE 106 | HISTORY WITH A DOMINO EFFECT 108 | PHOTO CREDITS 110 | MASTHEAD 2 CONTENTS 14 | AWAKENING 38 | REVOLUTION 78 | UNITY 16 | AGAINST THE DICTATORSHIP 40 | MORE AND MORE EAST GERMANS 80 | NO EXPERIMENTS 18 | THE PEACE AND ENVIRONMENTAL WANT OUT 84 | ON THE ROAD TO UNITY MOVEMENT IN THE GDR 44 | GRASSROOTS ORGANISATIONS 88 | GERMAN UNITY AND WORLD POLITICS 22 | it‘s not this countrY – 48 | REVOLTS ALONG THE RAILWAY LINE 90 | FREE WITHOUT BORDERS yOUTH CULTURES 50 | ANNIVERSARY PROTESTS 96 | THE COMPLETION OF UNITY 24 | SUBCULTURE 7 OCTOBER 1989 26 | THE OPPOSITION GOES PUBLIC 54 | EAST BErlin‘s gETHSEMANE CHURCH 30 | ARRESTS AND EXPULSIONS 56 | WE ARE THE PEOPLE! 34 | FIRST STEPS TO REVOLUTION 60 | THE SEd‘s nEW TACTIC 62 | THE CRUMBLING SYSTEM 66 | 4 NOVEMBER 1989 70 | 9 NOVEMBEr 1989 – THE FALL OF THE WALL 74 | THE BATTLE FOR POWER CONTENTS 3 4 IMPRESSIONS OF THE EXHIBITION INSTALLATION © SERGEJ HOROVITZ 5 6 IMPRESSIONS OF THE EXHIBITION INSTALLATION OPENING ADDRESS For Berlin, 2009 is a year of commemorations of the moving Central and Eastern European countries and Mikhail Gorbachev’s events of 20 years ago, when the Peaceful Revolution finally policy of glasnost and perestroika had laid the ground for change. toppled the Berlin Wall. The exhibition presented on Alexander- And across all the decades since the airlift 60 years ago, Berlin platz by the Robert Havemann Society is one of the highlights of was able to depend on the unprecedented solidarity of the Ameri cans, the theme year “20 Years since the Fall of the Wall”. -

Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Revised Pages Revised Pages Envisioning Socialism Television and the Cold War in the German Democratic Republic Heather L. Gumbert The University of Michigan Press Ann Arbor Revised Pages Copyright © by Heather L. Gumbert 2014 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (be- yond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid- free paper 2017 2016 2015 2014 5 4 3 2 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978– 0- 472– 11919– 6 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978– 0- 472– 12002– 4 (e- book) Revised Pages For my parents Revised Pages Revised Pages Contents Acknowledgments ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 1 Cold War Signals: Television Technology in the GDR 14 2 Inventing Television Programming in the GDR 36 3 The Revolution Wasn’t Televised: Political Discipline Confronts Live Television in 1956 60 4 Mediating the Berlin Wall: Television in August 1961 81 5 Coercion and Consent in Television Broadcasting: The Consequences of August 1961 105 6 Reaching Consensus on Television 135 Conclusion 158 Notes 165 Bibliography 217 Index 231 Revised Pages Revised Pages Acknowledgments This work is the product of more years than I would like to admit.