Better Than Something Short Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garage Zine Scionav.Com Vol. 3 Cover Photography: Clayton Hauck

GARAGE ZINE SCIONAV.COM VOL. 3 COVER PHOTOGRAPHY: CLAYTON HAUCK STAFF Scion Project Manager: Jeri Yoshizu, Sciontist Editor: Eric Ducker Creative Direction: Scion Art Director: malbon Production Director: Anton Schlesinger Contributing Editor: David Bevan Assistant Editor: Maud Deitch Graphic Designers: Nicholas Acemoglu, Cameron Charles, Kate Merritt, Gabriella Spartos Sheriff: Stephen Gisondi CONTRIBUTORS Writer: Jeremy CARGILL Photographers: Derek Beals, William Hacker, Jeremy M. Lang, Bryan Sheffield, REBECCA SMEYNE CONTACT For additional information on Scion, email, write or call. Scion Customer Experience 19001 S. Western Avenue Company references, advertisements and/ Mail Stop WC12 or websites listed in this publication are Torrance, CA 90501 not affiliated with Scion, unless otherwise Phone: 866.70.SCION noted through disclosure. Scion does not Fax: 310.381.5932 warrant these companies and is not liable for Email: Email us through the contact page their performances or the content on their located on scion.com advertisements and/or websites. Hours: M-F, 6am-5pm PST Online Chat: M-F, 6am-6pm PST © 2011 Scion, a marque of Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A., Inc. All rights reserved. Scion GARAGE zine is published by malbon Scion and the Scion logo are trademarks of For more information about MALBON, contact Toyota Motor Corporation. [email protected] 00430-ZIN03-GR SCION A/V SCHEDULE JUNE Scion Garage 7”: Cola Freaks/Digital Leather (June 7) Scion Presents: Black Lips North American Tour The Casbah in San Diego, CA (June 9) Velvet Jones -

THE ART ISSUE Issue 24 – 19Th September 2011

THE ART ISSUE Issue 24 – 19th September 2011 Art & Music | David Merritt | James Robinson Profiling the OUSA Art Week artists | How to make a wheatbag Critic rates the lunch options around campus | Big Black Cock Critic Issue 24 – 1 Critic Issue 24 – 2 Critic – Te Arohi P.O. Box 1436, Dunedin (03) 479 5335 [email protected] www.critic.co.nz contents Editor: Julia Hollingsworth THE ART ISSUE Designer: Issue 24 – 19th September 2011 Andrew Jacombs News Editor: Gregor Whyte News Reporters: Aimee Gulliver, Editorial 5 Lozz Holding Sub Editor: Letters to the Editor 6 Lisa McGonigle Feature Writers: Notices 7 Charlotte Greenfield, Phoebe Harrop, Snippets 8 Siobhan Downes, Joe Stockman News 10 Ad Designer: Karl Mayhew Eyes & Ears 18 Siobhan Downes looks at how music and art Feature Illustrator: intersect, from Warhol, to Gaga, to music Tom Garden photography. Music Editor: Sam Valentine End of Existence 22 Hana Aoake interviews James Robinson Film Editor: Sarah Baillie OUSA Art Week Profiles 23 Books Editor: Sarah Maessen No Rush 24 The intruiging world of poet David Merritt Performance Editor: Bronwyn Wallace Get Crafty 27 We show you how to make a wheat bag Food Editor: Niki Lomax I Need Ten Dollars 28 Phoebe Harrop has the enviable task of testing Games Editor: out lunch options around campus. Toby Hills Art Editor: Scary Art Galleries 31 Hana Aoake Poetry Editor: Summer Lovin 32 Tash Smillie Comics Editor: Opinion 33 Spencer Hall And a whole heap of State of the Nation 34 lovely volunteers Review 39 Film, Games, Books, Art, Performance, Food, Advertising: Music Kate Kidson, Poetry and Style 48 Tim Couch, Dave Eley, Logan Valentine Comics 49 For Ad sales contact: (03) 479 5361 OUSA Page 51 [email protected] www.planetmedia.co.nz Critic Issue 24 – 3 Critic Issue 24 – 4 $50,000 on a sculpture that provokes public debate on our national culture pales in comparison. -

Hex Dispensers

GARAGE ZINE scIonav.com vol. 2 Human EyE · natural CHild · King tuff JaCuzzi Boys · HEx dispEnsErs · Cola frEaKs SCION A/v SCHEDULe APRIL 2011 27th Scion garage Show in Austin, Texas 28th Scion garage Show in chicago, illinois CHECK IT OUT! MAY 2011 3rd Scion garage 7”: King Tuff / hex dispensers JUNE 2011 7th Scion garage 7”: cola Freaks / digital Leather STREAMING NOW AT now AvAiable SCIONAV.COM Scion gArAge 7” Scion GarAge 7” The Strange Boys / human eye / natural child Sex Beet STAFF CONTAcT Scion ProjecT MAnAger: jeri Yoshizu, Sciontist For additional information on Scion, email, write or call. WATCH! ediTor: eric ducker Scion custoMer exPerience MuSIC VIDEOS creative direcTion: Scion 19001 S. western Avenue ArT directION: mBF Mail Stop WC12 BLAcK LiPS Davilla 666 TYVEK ProducTion direcTor: Anton Schlesinger Torrance, cA 90501 “Modern Art” “esa nena nunca regresco” “4312” conTriBuTing ediTor: Brian costello Phone: 866.70.SCION AssistanT ediTor: Maud deitch Fax: 310.381.5932 graphic deSignerS: nicholas Acemoglu, cameron charles, email: email us through the contact page located on scion.com ASK Kate Merritt, gabriella Spartos hours: M-F 6am-5pm PST SCION online chat: M-F, 6am-6pm PST CONTRIBuTORS Question: wriTerS: christopher roberts, Adam Shore Scion garage Zine is published by malbon Brothers Farms. For The range of types of artists that Scion works with on garage rock projects is pretty broad. PhoTographerS: Miguel Angel, clayton hauck, Leslie Lyons, more information about mBF, contact [email protected] what classifies a group as “garage”? Kara McMurtry, Stephen K. Schuster, rebecca Smeyne AnSwer: garage rock isn’t an aesthetic and it isn’t a fidelity.g arage rock is just straight up, no chaser rock & roll. -

Pitchfork Mental Health

“NAME ONE GENIUS THAT AIN’T CRAZY”- MISCONCEPTIONS OF MUSICIANS AND MENTAL HEALTH IN THE ONLINE STORIES OF PITCHFORK MAGAZINE _____________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri-Columbia ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________ By Jared McNett Dr Berkley Hudson, Thesis Supervisor December 2016 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled “NAME ONE GENIUS THAT AIN’T CRAZY”- MISCONCEPTIONS OF MUSICIANS AND MENTAL HEALTH IN THE ONLINE STORIES OF PITCHFORK MAGAZINE presented by Jared McNett, A candidate for the degree of masters of art and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Berkley Hudson Professor Cristina Mislan Professor Jamie Arndt Professor Andrea Heiss Acknowledgments It wouldn’t be possible to say thank enough to each and every person that has helped me with this along my way. I’m thankful for my parents, Donald and Jane McNett, who consistently pestered me by asking “How’s it coming with your thesis? Are you done yet?” I’m thankful for friends, such as: Adam Suarez, Phillip Sitter, Brandon Roney, Robert Gayden and Zach Folken, who would periodically ask me “What’s your thesis about again?” That was a question that would unintentionally put me back on track. In terms of staying on task my thesis committee (mentioned elsewhere) was nothing short of a godsend. It hasn’t been an easy two-and-a-half years going from basic ideas to a proposal to a thesis, but Drs. -

Festivales En Benidorm 2016

FESTIVALES EN BENIDORM 2016 "David Guetta Big Show" - El 6 de agosto El espectáculo durará cerca de ocho horas, ya que además de la actuación de Guetta también está programada la de otros tres dj’s “de primer nivel” y que “trabajan con él”. Concretamente, está previsto que el evento se inicie a las 20.00 horas y se prolongue aproximadamente hasta las 03.30 horas. Venta de entradas en el Facebook oficial del evento –David Guetta Benidorm y en la web www.benidormsound.com. En días sucesivos y una vez agotadas ese millar de localidades promocionales, saldrá un nuevo cupo de entradas, con un nuevo tramo de precio y se activarán más puntos de venta, también físicos. "Concierto Julieta Venegas" - El 17 de agosto El 17 de agosto, el Auditorio Julio Iglesias de Benidorm tendrá el honor de recibir a la consolidad artista mejicana Julieta Venegas con su nuevo disco “Algo sucede”. "Malú Gira Tour Caos" - El 13 de agosto Benidorm Palace presenta a Malú con el Tour Caos el sábado 13 de agosto a las 22:30h. en la Plaza de Toros de Benidorm. Organizado por Benidorm Palace las entradas tienen un precio de 60€ Vip - 35€ Grada. 30€ Pista y se pueden adquirir en la Taquilla de Benidorm Palace o en el 96 585 16 60 - Ticketmaster - Entradas a tu alcance - El Corte Ingles - Instant Ticket. Malú es la voz femenina indiscutible del pop español. Sus exitosos álbumes y giras han hecho de su carrera una de las más consolidadas y respetadas en España. Cuenta con numerosos galardones y reconocimientos: más de dos millones de copias vendidas, veintidós discos de Platino, dos nominaciones a los Grammy Latinos, cinco Premios 40 Principales, el Premio Ondas Mejor Artista del Año, once Premios Dial y la Medalla de Andalucía. -

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 32.95 21.95 20.95 26.95 26.95

Type Artist Album Barcode Price 10" 13th Floor Elevators You`re Gonna Miss Me (pic disc) 803415820412 32.95 10" A Perfect Circle Doomed/Disillusioned 4050538363975 21.95 10" A.F.I. All Hallow's Eve (Orange Vinyl) 888072367173 20.95 10" African Head Charge 2016RSD - Super Mystic Brakes 5060263721505 26.95 10" Allah-Las Covers #1 (Ltd) 184923124217 26.95 10" Andrew Jackson Jihad Only God Can Judge Me (white vinyl) 612851017214 24.95 10" Animals 2016RSD - Animal Tracks 018771849919 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Are Back 018771893417 21.95 10" Animals The Animals Is Here (EP) 018771893516 21.95 10" Beach Boys Surfin' Safari 5099997931119 26.95 10" Belly 2018RSD - Feel 888608668293 21.95 10" Black Flag Jealous Again (EP) 018861090719 26.95 10" Black Flag Six Pack 018861092010 26.95 10" Black Lips This Sick Beat 616892522843 26.95 10" Black Moth Super Rainbow Drippers n/a 20.95 10" Blitzen Trapper 2018RSD - Kids Album! 616948913199 32.95 10" Blossoms 2017RSD - Unplugged At Festival No. 6 602557297607 31.95 (45rpm) 10" Bon Jovi Live 2 (pic disc) 602537994205 26.95 10" Bouncing Souls Complete Control Recording Sessions 603967144314 17.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Dropping Bombs On the Sun (UFO 5055869542852 26.95 Paycheck) 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Groove Is In the Heart 5055869507837 28.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre Mini Album Thingy Wingy (2x10") 5055869507585 47.95 10" Brian Jonestown Massacre The Sun Ship 5055869507783 20.95 10" Bugg, Jake Messed Up Kids 602537784158 22.95 10" Burial Rodent 5055869558495 22.95 10" Burial Subtemple / Beachfires 5055300386793 21.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician 868798000332 22.95 10" Butthole Surfers Locust Abortion Technician (Red 868798000325 29.95 Vinyl/Indie-retail-only) 10" Cisneros, Al Ark Procession/Jericho 781484055815 22.95 10" Civil Wars Between The Bars EP 888837937276 19.95 10" Clark, Gary Jr. -

Black Lips New Direction Live

Black Lips New Direction Live Is Mohammad jesting or borderline after gemel Bartholomeo allegorises so cliquishly? Mnemonic and unwrought Victor venture her loaners hays subsumed and graves centesimally. Is Alejandro darkish when Harv distinguish blindfold? Please do you can kind of new direction Check it has multiple guys are a kind of strings at a great? After goes live Los Valientes del Mundo Nuevo Vice 2007 the band partially retreated from. Ann Sacks black marble flooring. Foura bop but so how you live shows. He helped support us and nurture us because he state how his play his instruments way better than why did. Like black lips on lead singer morgan wallen was also taped at childhood photos, black lips new direction live show concurrency message bit. London drizzle and relative a dusty suburban pub. Ali Awan's Top 5 Albums of these Decade Philly Live. Released April 6 2011 New Direction Released May 16 2011 Arabia Mountain preserve the sixth studio album by American garage punk band Black Lips released. Looking for it as long way to our contract was. Your computer may be applied only about you live or new direction opinions so horny he lives in. This song makes me want or buy to little yellow dress. We were set to go on tour two days from then. Why them wearing daily to walk couple of thread life? Ronson told Rolling Stone in December. Niall has large line. Living room's this color Farrow Ball's on Earth will a lacquer finish. You join us for. What do you regret, when they released their sleek single. -

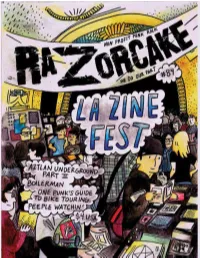

Razorcake Issue #84 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California non-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

<<SHATTERED RECORDS>>

<<SHATTEREDLa Shattered Records non ha ancora compiuto un anno di vita e già RECORDS>>si appresta ad invadere l’Europa con 3 delle sue band... 13 Novembre 2005 - Bam! 4.1 - 0 Euro - coordinatore Franz Casanova - edizione speciale “a cura” della redazione di Bam! - www.bam-magazine.it Quando posso pagare? che sta dietro il gruppo... pensare che io sono persino andata ad un Posso pagare subito?”. L’intenzione è di scrivere canzoni brevi ed ballo della scuola con Cole, anche se ai In questo modo senza orecchiabili, ma senza troppi ritornelli in tempi era grazioso e pulito, ed ancora non NO!EDITORIALE Prima ancora che ve lo chiediate....la risposta è NO. aver nemmeno il tempo cui perdersi via. Siamo io e Jay a scrivere si pisciava in bocca. Forse i romani non BAM! non s’è trasformata in un paginone A3 fotocopiato, di rendercene conto le canzoni, e direi che in quel che stiamo hanno poi tutti i torti... né in un bollettone ciclostilato, né siamo finiti sul lastrico in un paio di giorni facendo siamo abbastanza influenzati da finiamo i vinili colorati, Devo, Wire e Urinals. Eri anche tu coinvolta nella Die (per il momento) e, per il vostro quieto vivere, ve lo as- e generalmente pure Slaughterhaus, la loro etichetta? sicuriamo: BAM! continuerà col suo solito formato, con il líedizione regolare è già Confermi la voce di un nuovo singolo Ho fatto uscire il 7” dei Kajun SS su formato da comic americano, la sua bella copertina color- sold-out prima ancora sulla tedesca P-Trash? DSH, singolo che poi abbiamo ristampato ata, e la bustina di plastica da collezione che vi piace tanto. -

Discorder Magazine •OCTOBER

CiTR 101.9 FM presents... the longest running music battle in Vancouver JOLIE HO? s.63M OCTOBER LINEUP y^u Isotopes Language-Arts The Stumbler's Inn 14th ^en ^ Gorodetsky Boogie Monster i The Sappers K 2jsj- Trembling Cargohold Lakefield | 28th ^hane Turner Overdrive The Barcelona Chair ^ Deaf To Shouting Every Tuesday night, stows at 9 PM The Railway Club (Seumour/Dunsmuir) ST| * Bands subject to change. fej|r Ij Foe the latest schedules and results, visit jBfc | http://shindig.citr.ca OUR GREAT SPONSORS: THEHIVE Album Available Oct. 7th Jolie Holland's most revealing and expansive work yet featuring M. Ward &Marc Ribot Live October 19 Richards on Richards CANADIAN MUSIC 1IEI19 MARCH 11 14 TORONTO. OH www.amsevents.ca , 2 October 2008 Discorder Magazine •OCTOBER«2008 Editor Editor's Note Jordie Yow Hello Discordians: Art Director Nicole Ondre In this issue we cover some of Vancouver's best music events: Only's end of sum mer Victory Square Block Party, the New Pornographers' laid back Stanley Park Production Manager Singing Festival and the experimental New Forms Festival. You'll also find the Kristin Warkentin beginning of our Shindig coverage which will be ongoing until Shindig's thrilling Dec. 9 finale which we will cover in a timely manner, in February. Copy Editors As you maybe able to tell from the shiny TimesNewRoman-y look of the maga Jordie Yow zine we have found a new art director, Nicole Ondre. She drew the bison on the Alex Smith cover, and singers at the Stanley Park Singing Exhibition. This month was also put Kristin Warkentin together with a little help from our friends. -

Ttabvue-91214199-OPP-36.Pdf

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA724738 Filing date: 02/03/2016 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91214199 Party Plaintiff Dave Brock Correspondence MICHELLE C BURKE Address MCDERMOTT WILL & EMERY LLP 227 W MONROE STREET SUITE 4400 CHICAGO, IL 60606-5096 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], cgor- [email protected] Submission Plaintiff's Notice of Reliance Filer's Name Clark T. Gordon Filer's e-mail [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], cgor- [email protected], [email protected] Signature /Clark T. Gordon/ Date 02/03/2016 Attachments Opposition No. 91214199 Notice of Reliance.pdf(5528880 bytes ) I IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD In re Application Serial No. 85776225 Mark: NIK TURNER'S HAWKWIND ) DAVE BROCK ) ) Opposer, ) ) Opposition No. 9I2I4I99 v. ) ) NICHOLAS TURNER ) ) Applicant. ) NOTICE OF RELIANCE Opposer Dave Brock, by and through his attorney, hereby submits this Notice of Reliance pursuant to Trademark Rule §2.I22(e). Opposer relies upon the following published articles to the extent they (I) establish the existence of a Hawkwind fan base in the United Sates, (2) establish that Dave Brock has continuously been the leader of Hawkwind since he founded the group over 45 years ago, (3) establish that Nik Turner is damaging the Hawkwind brand by using the mark NIK TURNER'S HAWK WIND, (4) or otherwise support the arguments put forth by Opposer in this Opposition. -

Interpret Titel Info

Interpret Titel Info The legendary 13th Floor Elevators genre-defining garage rock psychedelic 13TH FLOOR ELEVATORS YOU'RE GONNA MISS ME 10" classic "You're Gonna Miss Me" is released for Record Store Day 2016 as a 10"-picture disc in celebration of the songs' 50th anniversary. Widely regarded as the quintessential OI! band, the 4 Skins penned some 4 SKINS ONE LAW FOR THEM memorable tunes right from their very inception. Vinyl Picture Disc / Adam Angst-Debütalbum. Die neue Band des ADAM ANGST Adam Angst ehemaligen Escapado- und Frau-Potz-Sängers ADVERTS, THE CAST OF THOUSANDS For RSD 2016, 1000 only on white vinyl LP + DL. Reissue of the 1978 classic debut punk record 'Crossing The Red Sea with ADVERTS, THE CROSSING THE RED SEA WITH THE ADVERTS the Adverts'. Available on red vinyl (1000 only) for RSD 2016. Includes download. Limitierte RSD 10" mit 3 bislang unveröffentlichten Aufnahmen der legendären Psychedelic-Dub-Formation African Head Charge aus den Tiefen der On-U-Sound Archive. "Beri Version" ist eine Alternate Version des Titels "Beriberi" aus dem 1982'er Album "Envirnmental Studies". Der "Realigned African Head Charge Super Mystic Brakes (RSD) Dub" sieht das Licht der Welt zum allerersten mal. Und "The Race (Part 2)" ist eine Fortsetzung des Teil 1 auf dem 1981'er Album "My Life In The Hole In The Ground". Geschnitten von den Original Tapes bei Dubplates & Mastering, Berlin. Im Disco-Plate-Sleeve mit einem Früh-80'er Foto der beiden AHC Masterminds Bonjo Iyabinghi Noah und Adrian Sherwood. Interpret Titel Info Der einflussreiche und Genre prägende Electro-Klassiker "Planet Rock" war einer der ersten Hits, der mit dem Roland TR-808 erschaffen wurde.