Master Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann (Pdf)

6/28/2020 The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann » Mosaic THE TRUTH OF THE CAPTURE OF ADOLF EICHMANN https://mosaicmagazine.com/essay/history-ideas/2020/06/the-truth-of-the-capture-of-adolf-eichmann/ Sixty years ago, the infamous Nazi official was abducted in Argentina and brought to Israel. What really happened, what did Hollywood make up, and why? June 1, 2020 | Martin Kramer About the author: Martin Kramer teaches Middle Eastern history and served as founding president at Shalem College in Jerusalem, and is the Koret distinguished fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Listen to this essay: Adolf Eichmann’s Argentinian ID, under the alias Ricardo Klement, found on him the night of his abduction. Yad Vashem. THE MOSAIC MONTHLY ESSAY • EPISODE 2 June: The Truth of the Capture of Adolf Eichmann 1x 00:00|60:58 Sixty years ago last month, on the evening of May 23, 1960, the Israeli prime minister David Ben-Gurion made a brief but dramatic announcement to a hastily-summoned session of the Knesset in Jerusalem: A short time ago, Israeli security services found one of the greatest of the Nazi war criminals, Adolf Eichmann, who was responsible, together with the Nazi leaders, for what they called “the final solution” of the Jewish question, that is, the extermination of six million of the Jews of Europe. Eichmann is already under arrest in Israel and will shortly be placed on trial in Israel under the terms of the law for the trial of Nazis and their collaborators. In the cabinet meeting immediately preceding this announcement, Ben-Gurion’s ministers had expressed their astonishment and curiosity. -

Fauda : Zoom Avant Sur Le Chaos ÉRIC CLÉMENS L’Europe Devant La Question Juive BRUNO KARSENTI L’État Juif Est Un État Fait Pour Les Juifs JACQUES SOJCHER Israël

Editorial, Richard Miller DOSSIER ISRAËL FRANÇOIS ENGLERT Hommage aux Justes : témoignage d’un enfant caché MICHEL GHEUDE Le sujet qui fâche RICHARD MILLER Du Bauhaus au sionisme ÉLIE BARNAVI L’après Rabin ère GUY HAARSCHER N° 1 1 année – Automne 2019 N° 1 « Pro Israël Pro Peace » Fondateurs : Richard Miller et Jean Meurice THE AGREEMENT DE DAVID BROGNON ET STÉPHANIE ROLLIN DOMINIQUE COSTERMANS PHILOSOPHIE . CULTURE . POLITIQUE . ART Fauda : zoom avant sur le chaos ÉRIC CLÉMENS L’Europe devant la question juive BRUNO KARSENTI L’État juif est un État fait pour les Juifs JACQUES SOJCHER Israël Sionisme, antisionisme et antisémitisme TESSA PARZENCZEWSKI À travers romans et nouvelles, que nous dit Amos Oz ? JACQUES BROTCHI Mon vœu le plus cher : une solution à deux Etats DOSSIER VARIA VINCENT DE COOREBYTER Aux origines de la laïcité Israël FRANÇOIS ENGLERT, MICHEL GHEUDE, RICHARD MILLER, ELIE BARNAVI, LUC RICHIR GUY HAARSCHER, DOMINIQUE COSTERMANS, ERIC CLÉMENS, BRUNO KARSENTI, JACQUES SOJCHER, TESSA PARZENCZEWSKI, JACQUES BROTCHI Le dernier homme DOSSIER LAMBROS COULOUBARITSIS VARIA : VINCENT DE COOREBYTER, LUC RICHIR, LAMBROS COULOUBARITSIS De la multi-culturalité à l’inter-culturalité européenne Ulenspiegel ACTUALITÉS DES EDITIONS DU CEP VÉRONIQUE BERGEN L’odyssée poético-politique de Jean-Louis Lippert FÉLIX HANNAERT peintures dessins/schildereien tekeningen/1980 2020 Cahier d’illustrations : Photographies et dessins en rapport avec des textes Les éditions du CEP Créations . Europe . Perspectives 14 € Créations . Europe . Perspectives Dominique Costermans Fauda : zoom avant sur le chaos Fauda arrive, Fauda revient. À l’origine conçue pour un public israélien, la série de Lior Raz et d’Avi Issacharoff a désormais conquis une audience internationale depuis sa diffusion par Netflix. -

Countering the Plunder and Sale of Priceless Cultural Antiquities by Isis

PREVENTING CULTURAL GENOCIDE: COUNTERING THE PLUNDER AND SALE OF PRICELESS CULTURAL ANTIQUITIES BY ISIS HEARING BEFORE THE TASK FORCE TO INVESTIGATE TERRORISM FINANCING OF THE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION APRIL 19, 2016 Printed for the use of the Committee on Financial Services Serial No. 114–83 ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 23–891 PDF WASHINGTON : 2017 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 17:07 Aug 14, 2017 Jkt 023891 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 K:\DOCS\23891.TXT TERI HOUSE COMMITTEE ON FINANCIAL SERVICES JEB HENSARLING, Texas, Chairman PATRICK T. MCHENRY, North Carolina, MAXINE WATERS, California, Ranking Vice Chairman Member PETER T. KING, New York CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York EDWARD R. ROYCE, California NYDIA M. VELA´ ZQUEZ, New York FRANK D. LUCAS, Oklahoma BRAD SHERMAN, California SCOTT GARRETT, New Jersey GREGORY W. MEEKS, New York RANDY NEUGEBAUER, Texas MICHAEL E. CAPUANO, Massachusetts STEVAN PEARCE, New Mexico RUBE´ N HINOJOSA, Texas BILL POSEY, Florida WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri MICHAEL G. FITZPATRICK, Pennsylvania STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts LYNN A. WESTMORELAND, Georgia DAVID SCOTT, Georgia BLAINE LUETKEMEYER, Missouri AL GREEN, Texas BILL HUIZENGA, Michigan EMANUEL CLEAVER, Missouri SEAN P. DUFFY, Wisconsin GWEN MOORE, Wisconsin ROBERT HURT, Virginia KEITH ELLISON, Minnesota STEVE STIVERS, Ohio ED PERLMUTTER, Colorado STEPHEN LEE FINCHER, Tennessee JAMES A. -

A Comparative Analysis of Cnn and Al Jazeera's Coverage

A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF CNN AND AL JAZEERA’S COVERAGE OF THE PALESTINIAN- ISRAELI CONFLICT OF 2014 BY HALIMA SADIYYA ADAMU P13SSMM8011 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF POSTGRADUATE STUDIES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY ZARIA, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE IN MASS COMMUNICATION DEPARTMENT OF MASS COMMUNICATION, FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA OCTOBER, 2018 1 DECLARATION I declare that the work in this dissertation entitled A Comparative Analysis of CNN and Al Jazeera English Coverage of the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict of 2014 was written by me in the department of Mass Communication. The information derived from the literature has been duly acknowledged in the text and a list of references provided. No part of this thesis has been presented for the award of any form of academic qualification at this, or any other academic institution. _________________________ ________________________Halima Sadiyya Adamu Date P13SSMM8011 2 CERTIFICATION This dissertation entitled A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF CNN AND AL JAZEERA‘S COVERAGE OF THE PALESTINIAN-ISRAELI CONFLICT OF 2014 by ADAMU HALIMA SADIYYA meets the regulations governing the award of the degree of Masters of Science (M.S.c Hons) in Mass Communication of the Ahmadu Bello University, and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. Mal. Usman Jimada ______________________ __________________ Chairman, Supervisory Committee Date Dr. Ibrahim Jimoh _______________________ __________________ Member, Supervisory Committee Date Dr. Mahmood Umar ________________________ __________________ Head of Department Date Prof. Sadiq Z. Abubakar _____________________ _________________ Dean, School of Postgraduate Studies Date 3 DEDICATION For my beloved late father, Mallam Sa‘idu Hassan Adamu (Paapa) who was always so proud of me. -

Nimrod Barkan > P

THANK YOU FOR SUPPORTING OUR TU BI’SHEVAT CAMPAIGN VISIT ISRAEL WITH JNF: JNFOTTAWA.CA [email protected] 613.798.2411 Ottawa Jewish Bulletin FEBRUARY 20, 2017 | 24 SHEVAT 577 ESTABLISHED 1937 OTTAWAJEWISHBULLETIN.COM | $2 Hundreds gather to do good deeds on Mitzvah Day Mitzvah Day 2017 was marked by the performance of good deeds by young and old – and those in between – along with a celebration of Canada 150. Louise Rachlis reports. he Soloway Jewish Community Lianne Lang of CTV was MC for the Centre (SJCC) and Hillel Lodge event. She praised the “hard work and were buzzing with activity as dedication” of Mitzvah Day Chair Cindy ISSIE SCAROWSKY Eli Saikaley of Silver Scissors Salon supervises Mitzvah Day celebrity haircutters (from left) hundreds of volunteers – from Smith and her planning committee, and T Jeff Miller of GGFL, Mayor Jim Watson and City Councillor Jean Cloutier as they prepare to cut at preschoolers to seniors – gathered, acknowledged the Friends of Mitzvah least six inches of hair from Sarah Massad, Yasmin Vinograd and Liora Shapiro to be used by February 5, on the Jewish Community Day for their support, and GGFL Hair Donation Ottawa to make wigs for cancer patients experiencing medical hair loss. Campus and several off-site locations, to Chartered Professional Accountants, the participate in the Jewish Federation of Mitzvah Day major sponsor for the past Ottawa’s annual Mitzvah Day. eight years. In recognition of Canada’s sesquicen- Hair donations for Hair Donation tennial, a Canada 150 theme was incor- Ottawa – an organization that provides porated into many of the good deeds free wigs for cancer patients experiencing performed. -

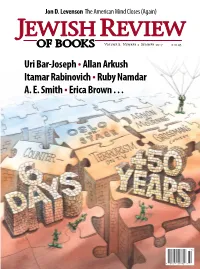

Uri Bar-Joseph •Allan Arkush Itamar Rabinovich •Ruby Namdar A. E

Jon D. Levenson The American Mind Closes (Again) JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 8, Number 2 Summer 2017 $10.45 Uri Bar-Joseph • Allan Arkush Itamar Rabinovich • Ruby Namdar A. E. Smith • Erica Brown . Editor Abraham Socher FASCINATING SERIES BY MAGGID BOOKS Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush Art Director Betsy Klarfeld MAGGID MODERN CLASSICS Managing Editor Introduces one of Israel’s most creative and influential thinkers Amy Newman Smith Editorial Assistant Kate Elinsky FAITH SHATTERED Editorial Board AND RESTORED Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Judaism in the Postmodern Age Rabbi Shagar Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Jon D. Levenson The starkly innovative spiritual and educational Anita Shapira Michael Walzer approach of Rabbi Shimon Gershon Rosenberg J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier (known as Rabbi Shagar) has shaped a generation of Israelis who yearn to encounter the Divine in a world Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein progressively at odds with religious experience, nurturing religious faith within a cultural climate Publisher of corrosive skepticism. Here, Rabbi Shagar offers Eric Cohen profound and often acutely personal insights that marry existentialist philosophy and Hasidism, Advancement Officer Talmud and postmodernism. Malka Groden Published for Associate Publisher the 1st time The seminal essays in Faith Shattered and Restored in English! sets out a new path for preserving and cultivating Dalya Mayer Jewish spirituality in the 21st century and beyond. Chairman’s Council Anonymous Blavatnik Family Foundation Publication Committee Marilyn and Michael Fedak Ahuva and Martin J. Gross Susan and Roger Hertog MAGGID STUDIES IN TANAKH Roy J. Katzovicz Inaugurates new volume on Humash. The Lauder Foundation– Leonard and Judy Lauder Tina and Steven Price Charitable Foundation Pamela and George Rohr GENESIS Daniel Senor From Creation to Covenant Paul E. -

Steve Tamari Shareholder Proposal (College Retirement Equities Fund)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 DIVISION OF May 10,2013 INVESTMENT MANAGEMENT Phillip T. Rollock Senior Managing Director and Corporate Secretary College Retirement Equities Fund 730 Third Avenue New York, NY 10017-3206 Re: College Retirement Equities Fund ("Fund") Shareholder Proposal of Steve Tamari Dear Mr. Rollock: In a letter dated March 22, 2013, you notified the staff of the Securities and Exchange Commission ("Commission") that the Fund intends to omit from its proxy materials for its 2013 annual meeting a shareholder proposal submitted by Steve Tamari in a letter dated January 14, 2013. 1 The proposal provides : THEREFORE, shareholders request that the Board end investments in companies that, in the trustees' judgment, substantially contribute to or enable egregious violations ofhuman rights, including companies whose business supports Israel 's occupation. There appears to be some basis for your view that the Fund may omit the proposal from the Fund's proxy materials pursuant to Rule 14a-8(i)(10) under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, which permits omission of a proposal that has been substantially implemented. Accordingly, the Division of Investment Management ("Division") will not recommend enforcement action to the Commission if the Fund omits the proposal from its proxy materials in reliance on Rule 14a-8(i)(1 0). In reaching this position, we have not found it necessary to address the alternative bases for omission set forth in your letter. Because our position is based upon the facts recited in your letter, different facts or conditions or additional facts or conditions may require a different conclusion. -

Zionist Exclusivism and Palestinian Responses

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kent Academic Repository UNIVERSITY OF KENT SCHOOL OF ENGLISH ‘Bulwark against Asia’: Zionist Exclusivism and Palestinian Responses Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. in Postcolonial Studies at University of Kent in 2015 by Nora Scholtes CONTENTS Abstract i Acknowledgments ii Abbreviations iii 1 INTRODUCTION: HERZL’S COLONIAL IDEA 1 2 FOUNDATIONS: ZIONIST CONSTRUCTIONS OF JEWISH DIFFERENCE AND SECURITY 40 2.1 ZIONISM AND ANTI-SEMITISM 42 2.2 FROM MINORITY TO MAJORITY: A QUESTION OF MIGHT 75 2.3 HOMELAND (IN)SECURITY: ROOTING AND UPROOTING 94 3 ERASURES: REAPPROPRIATING PALESTINIAN HISTORY 105 3.1 HIDDEN HISTORIES I: OTTOMAN PALESTINE 110 3.2 HIDDEN HISTORIES II: ARAB JEWS 136 3.3 REIMAGINING THE LAND AS ONE 166 4 ESCALATIONS: ISRAEL’S WALLING 175 4.1 WALLING OUT: FORTRESS ISRAEL 178 4.2 WALLED IN: OCCUPATION DIARIES 193 CONCLUSION 239 WORKS CITED 245 SUPPLEMENTARY BIBLIOGRAPHY 258 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a consideration of how the ideological foundations of Zionism determine the movement’s exclusive relationship with an outside world that is posited at large and the native Palestinian population specifically. Contesting Israel’s exceptionalist security narrative, it identifies, through an extensive examination of the writings of Theodor Herzl, the overlapping settler colonialist and ethno-nationalist roots of Zionism. In doing so, it contextualises Herzl’s movement as a hegemonic political force that embraced the dominant European discourses of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including anti-Semitism. The thesis is also concerned with the ways in which these ideological foundations came to bear on the Palestinian and broader Ottoman contexts. -

Positive Energy a Review of the Role of Artistic Activities in Refugee Camps

UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES POLICY DEVELOPMENT AND EVALUATION SERVICE (PDES) Positive energy A review of the role of artistic activities in refugee camps Awet Andemicael PDES/2011/06 [email protected] June 2011 Policy Development and Evaluation Service UNHCR‘s Policy Development and Evaluation Service (PDES) is committed to the systematic examination and assessment of UNHCR policies, programmes, projects and practices. PDES also promotes rigorous research on issues related to the work of UNHCR and encourages an active exchange of ideas and information between humanitarian practitioners, policymakers and the research community. All of these activities are undertaken with the purpose of strengthening UNHCR‘s operational effectiveness, thereby enhancing the organization‘s capacity to fulfill its mandate on behalf of refugees and other persons of concern to the Office. The work of the unit is guided by the principles of transparency, independence, consultation, relevance and integrity. Policy Development and Evaluation Service United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Case Postale 2500 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland Tel: (41 22) 739 8433 Fax: (41 22) 739 7344 e-mail: [email protected] internet: www.unhcr.org Printed in UNHCR All PDES evaluation reports are placed in the public domain. Electronic versions are posted on the UNHCR website and hard copies can be obtained by contacting PDES. They may be quoted, cited and copied, provided that the source is acknowledged. The views expressed in PDES publications are those of the author and are not necessarily those of UNHCR. The designations and maps used do not imply the expression of any opinion or recognition on the part of UNHCR concerning the legal status of a territory or of its authorities. -

May 1, 2018 16 Iyar 5778

The Aaronion 616 S. Mississippi River Blvd, St. Paul, MN 55116- 1099 • (651) 698 -8874 • www.TempleofAaron.org Vol. 93 • No. 9 May 1, 2018 16 Iyar 5778 Minnesota’s Annual AIPAC Event May 3, 2018 AIPAC invites you to hear A Year of Veganism Mosab Hassann Yousef, In 2017, we were honored to receive a grant from the author of Son of Hamas , the Jewish organization Shamayim V’Aretz which is a former Hamas operative. devoted to ethical eating and treatment of animals. This grant contained a challenging question for the staff: How do we use food to engage the concepts of Kashrut and mirror them with a modern Jewish approach? From an Israeli vegan lunch to collaborating with local Kosher and vegan vendors, the grant enabled Rabbi Jeremy Fine Temple of Aaron to create a new way for us to think 651 -698 -8874 x112 about one of the pillars of Judaism. I want to thank Email: member Howard Goldman for helping recruit [email protected] Twitter: Christine Coughlin who spoke on ethical eating and @RabbiJeremyFine all of you who have come to these events with an open mind (and belly). Trying a “new” way of eating or a Jewish experience takes an incredible amount of openness. Whether it be a change in the synagogue or in the home, Jewish customs Mosab Hassan Yousef was born in need constant innovative approaches to allow all of us the access holidays and Ramallah, in Israel’s West Bank in rituals. 1978. His father, Sheikh Hassan Yousef, is a founding leader of Hamas, Shavuot is a break from our constant. -

Remembering Al-Andalus: Ṣūfī Pathways of Engagement Between Jews and Muslims in Israel and Their Contribution to Reconciliation and Conflict Transformation

THE UNIVERSITY OF WINCHESTER ABSTRACT FOR THESIS Remembering Al-Andalus: Ṣūfī Pathways of Engagement Between Jews and Muslims in Israel and Their Contribution to Reconciliation and Conflict Transformation Katherine Randall Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Doctor of Philosophy March 2014 This doctoral thesis investigates the practice of Sufism and Ṣūfī inspired activities among Jews and Muslims in Israel and examines their potential contribution to peace and reconciliation by creating pathways of engagement between members of the two faith traditions. The history of the interreligious encounters between Muslim and Jewish mystics in medieval Al-Andalus and Fustāt, Egypt is presented as the narrative of a heritage common to Jews and Muslims practising Sufism together in contemporary Israel. The examples of Ṣūfī practice in Israel that are revealed in this study demonstrate the continuity of such exchanges. The narratives of Israeli-Jews who are engaging regularly with Israeli-Muslim-Ṣūfīs form the primary source material for the study. The narrators consist of those who identify themselves as Jewish-Ṣūfīs; those who have adopted Ṣūfī concepts and practices; those who have gained an insider perspective of Sufism but who do not define themselves as Ṣūfīs; and those who have taken hand with a Muslim Ṣūfī Shaykh in the traditional manner of the Ṣūfī orders. They all remain rooted in their own Jewish faith and see no dissonance in the adoption of traditionally Ṣūfī practices to pursue a path of spiritual progression. The focus of the investigation on the potential of Sufism in Israel to provide a channel of mutual engagement between Jews and Muslims situates the thesis within the discipline of Ṣūfī Studies while also constituting an original contribution to academic studies on conflict transformation and Jewish-Muslim relations. -

Nov 5-21, 2017 Los Angeles

NOV 5-21, 2017 LOS ANGELES WWW.ISRAELFILMFESTIVAL.COM © 2017 A presentation of the IsraFest Foundation, Inc. Key art designed by eclipse. FILM GUIDE | SCREENING SCHEDULE | EVENTS MISSION AND HONORARY COMMITTEE NOTE FROM THE FESTIVAL’S FOUNDER & EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR HONORARY MEIR FENIGSTEIN COMMITTEE FOUNDER / DIRECTOR WELCOME TO THE 31ST ISRAEL FILM FESTIVAL Meir Fenigstein CHAIRMAN Adam Berkowitz Dear Friends, HONORARY CHAIRMAN Arnon Milchan On behalf of the IsraFest Foundation, Inc. and its family of filmmakers and sponsors, I would like to welcome you to our 31ST ISRAEL FILM FESTIVAL in Los Angeles. HONORARY COMMITTEE This is an exciting chapter in our Festival’s ongoing adventure, as we start our 4th Sheldon G. Adelson decade as the largest showcase of Israeli films in the United States, and one of its Beny Alagem oldest and most prestigious foreign film festivals. Gila Almagor This year we are pleased to introduce close to 40 new feature films, thought- Avi Arad provoking documentaries, innovative television series, and award-winning shorts. Arthur Cohen 25 Israeli filmmakers will attend the various screenings and events to meet the Beverly Cohen audience and introduce their work. We are proud to announce our first ever Robert DeNiro television-focused program: Israeli TV – An American Success Story as we celebrate the success of Israeli television in the American marketplace. Danny Dimbort Michael Douglas We extend our sincerest congratulations to this year’s Festival honorees Jeffrey Richard Dreyfuss Tambor, recipient of the 2017 IFF Achievement in Television Award, and Lior Meyer Gottlieb Ashkenazi, recipient of the 2017 Cinematic Achievement Award, for their amazing Peter Guber accomplishments, as well as their abiding friendship to Israel and Israeli culture.