Sue Joseph What If Tom Wolfe Was Australian?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Journalism'; Eyewitness Report by Tom Wolfe Participant Reveals Main Factors Leading to Demise of the Novel, Rise of New Style Covering Events by Tom Wolfe

Tom Wolfe Gives an Eyewitness Report of the Birth of 'The Ne... http://nymag.com/news/media/47353/ The Birth of 'The New Journalism'; Eyewitness Report by Tom Wolfe Participant Reveals Main Factors Leading to Demise of the Novel, Rise of New Style Covering Events By Tom Wolfe From the February 14, 1972 issue of New York Magazine. I. The Feature Game doubt if many of the aces I will be I extolling in this story went into journalism with the faintest notion of creating a "new" journalism, a "higher" journalism, or even a mildly improved variety. I know they never dreamed that anything they were going to write for newspapers or magazines would wreak such evil havoc in the literary world . causing panic, dethroning the novel as the number one literary genre, starting the first new direction in American literature in half a century . Nevertheless, that is what has happened. Bellow, Barth, Updike—even the best of the lot, Philip Roth—the novelists are all out there ransacking the literary histories and sweating it out, wondering where they now stand. Damn it all, Saul, the Huns have arrived. God knows I didn't have anything new in mind, much less anything literary, when I took my first newspaper job. I had a fierce and unnatural craving for something else entirely. Chicago, 1928, that was the general idea . Drunken reporters out on the ledge of the News peeing into the Chicago River at dawn . Nights down at the saloon listening to "Back of the Stockyards" being sung by a baritone who was only a lonely blind bulldyke with lumps of milk glass for eyes . -

Personal Frameworks and Subjective Truth: New Journalism and the 1972 U.S

PERSONAL FRAMEWORKS AND SUBJECTIVE TRUTH: NEW JOURNALISM AND THE 1972 U.S. PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION BY ASHLEE AMANDA NELSON A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington 2017 2 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the reportage of the New Journalists who covered the United States 1972 presidential campaign. Nineteen seventy-two was a key year in the development of New Journalism, marking a peak in output from successful writers, as well as in the critical attention paid to debates about the mode. Nineteen seventy-two was also an important year in the development of campaign journalism, a system which only occurred every four years and had not changed significantly since the time of Theodore Roosevelt. The system was not equipped to deal with the socio-political chaos of the time, or the attempts by Richard Nixon at manipulating how the campaign was covered. New Journalism was a mode founded in part on the idea that old methods of journalism needed to change to meet the needs of contemporary society, and in their coverage of the 1972 campaign the New Journalists were able to apply their arguments for change to their campaign reportage. Thus the convergence of the campaign reportage cycle with the peak of New Journalism’s development represents a key moment in the development of both New Journalism and campaign journalism. I use the campaign reportage of Timothy Crouse in The Boys on the Bus, Norman Mailer in St. George and the Godfather, Hunter S. -

52 Literary Journalism Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, Spring 2016

52 Literary Journalism Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1, Spring 2016 Above: Author Tracy Kidder. Photograph by Gabriel Amadeus Cooney. Right: Author John D’Agata. 53 Beyond the Program Era: Tracy Kidder, John D’Agata, and the Rise of Literary Journalism at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop David Dowling University of Iowa, United States Abstract: The Iowa Writers’ Workshop’s influence on literary journalism -ex tends beyond instructional method to its production of two writers who al- ternately sustained the traditions of the genre and boldly defied them: Tracy Kidder, who forged his career during the heyday of the New Journalism in the early 1970s, and John D’Agata, today’s most controversial author chal- lenging the boundaries of literary nonfiction. This essay examines the key works of Kidder and D’Agata as expressions of and reactions to Tom Wolfe’s exhortation for a new social realism and literary renaissance fusing novelis- tic narrative with journalistic reporting and writing. Whereas a great deal of attention has been paid to Iowa’s impact on the formation of the postwar literary canon in poetry and fiction, its profound influence on literary jour- nalism within the broader world of creative writing has received little no- tice. Through archival research, original interviews, and textual explication, I argue that Kidder’s narrative nonfiction reinforces Wolfe’s conception of social realism, as theorized in “Stalking the Billion-Footed Beast,” in sharp contrast to D’Agata’s self-reflexive experimentation, toward a more liber- ally defined category of creative writing. Norman Sims defended literary journalists’ immersion in “complex, difficult subjects” and narration “with a voice that allows complexity and contradiction,” countering critics who claimed their work “was not always accurate.” D’Agata has reopened the de- bate by exposing the narrative craft’s fraught and turbulent relation to fact. -

The New Journalism Free

FREE THE NEW JOURNALISM PDF Tom Wolfe | 432 pages | 01 Feb 2010 | Pan MacMillan | 9780330243155 | English, Spanish | London, United Kingdom New Journalism - Wikipedia Goodreads The New Journalism you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read The New Journalism Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. The New Journalism by Tom Wolfe. Get A Copy. Paperbackpages. Published January 1st by HarperCollins Publishers. More Details Original Title. Other Editions 6. Friend Reviews. To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign The New Journalism. To The New Journalism other readers questions about The New Journalismplease sign up. Goodreader help me on how to read my book or must I click to read? See 1 question about The New Journalism…. Lists with This Book. Community Reviews. Showing Average rating 4. Rating details. More filters. Sort order. Start your review of The New Journalism. May 16, Florencia rated it really liked it Shelves: non-fictionde-nuntium. The book is also an anthology. Norman Mailer, Rex Reed and John Dunne are some of the journalists whose work The New Journalism been added to this wonderful collection. It was published in The New Herald Tribune in Repulsive and yet enthralling. There are a couple of things I found a tad annoying. An excessive use of exclamation marks, onomatopoeia, dashes and dots everywhere? Nevertheless, this is nothing but a detail when discussing accuracy and verifiability, which by no means should be sacrificed to give creativity The New Journalism more important role. -

1 Masteroppgave I Engelsk Hunter S. Thompson and Gonzo Journalism

Masteroppgave i Engelsk Hunter S. Thompson and Gonzo Journalism Av Frode Vågsdalen Masteroppgaven er gjennomført som et ledd i utdanningen ved Universitetet i Agder og er godkjent som sådan. Denne godkjenningen innebærer ikke at universitetet innestår for de metoder som er anvendt og de konklusjoner som er trukket. Veileder: Michael J. Prince Universitetet i Agder, Kristiansand Vår 2008 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my advisor Michael J. Prince for feedback and pep talks whenever circumstance demanded it. Thank you for supporting me through the project and for guiding me ashore. My fellow students have inspired me tremendously over the last two years, and our conversations and support at the study hall have been of invaluable importance when the going has been tough. Thank you all. The process of writing a master thesis takes its toll on both student as well as surroundings, and there has been made sacrifices on both sides. Family and social life has been replaced with a considerable amount of hours in front of books and computers, but what an interesting ride it’s been….after all. 2 So we shall let the reader answer the question for himself. Who is the happier man, he who has braved the storm of life and lived, 1 or he who has stayed securely on shore and merely existed? 1 Carroll: 1993: 279 3 Introduction __________________________________________________________________5 Literary Journalism, New Journalism and Gonzo Journalism __________________________9 Hell’s Angels: the Strange and Terrible Saga Of the Outlaw Motorcycle -

The Birth of 'The New Journalism'; Eyewitness Report by Tom Wolfe

2/1/2016 Tom Wolfe Gives an Eyewitness Report of the Birth of 'The New Journalism' -- New York Magazine The Birth of 'The New Journalism'; Eyewitness Report by Tom Wolfe Participant Reveals Main Factors Leading to Demise of the Novel, Rise of New Style Covering Events By Tom Wolfe From the February 14, 1972 issue of New York Magazine. I. The Feature Game doubt if many of the aces I will be I extolling in this story went into journalism with the faintest notion of creating a "new" journalism, a "higher" journalism, or even a mildly improved variety. I know they never dreamed that anything they were going to write for newspapers or magazines would wreak such evil havoc in the literary world . causing panic, dethroning the novel as the number one literary genre, starting the first new direction in American literature in half a century . Nevertheless, that is what has happened. Bellow, Barth, Updike—even the best of the lot, Philip Roth— the novelists are all out there ransacking the literary histories and sweating it out, wondering where they now stand. Damn it all, Saul, the Huns have arrived. God knows I didn't have anything new in mind, much less anything literary, when I took my first newspaper job. I had a fierce and unnatural craving for something else entirely. Chicago, 1928, that was the general idea . Drunken reporters out on the ledge of the News peeing into the Chicago River at dawn . Nights down at the saloon listening to "Back of the Stockyards" being sung by a baritone who was only a lonely blind bulldyke with lumps of milk glass for eyes . -

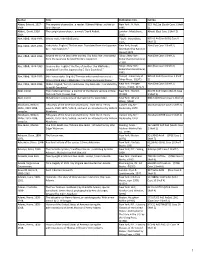

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel. -

The New Journalism and Its Editors: Hunter S

THE NEW JOURNALISM AND ITS EDITORS: HUNTER S. THOMPSON, TOM WOLFE, AND THEIR EARLY EXPERIENCES By ELI JUSTIN BORTZ A THESIS PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MASS COMMUNICATION UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2005 Copyright 2005 by Eli Justin Bortz This document is dedicated to Meredith Ridenour, who provided only patience, guidance, and love throughout this project, and Hunter S. Thompson, whose wordplay continues to resonate. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As I worked on this thesis over the last two years, I attempted to keep a list in my mind of everyone I needed to thank. As the list grew, I realized I was bound to forget names. Indeed, so many people provided guidance, help, and support that imagining the list is fairly overwhelming. I must first thank the chair of my supervisory committee, Dr. Bernell Tripp, for providing remarkable patience and advice as this project developed and progressed. I realized early on that I would need someone with an editor’s eye to guide my writing. She provided that, and more. It was with her encouragement that I was able to complete this project. I am also indebted to my other committee member, Dr. William McKeen, who accepted the task of serving on my committee during what can only be described as a busy time in his life. I wish him and his growing family all the best. Dr. Leonard Tipton, my other committee member, gave me encouragement and advice in the earliest stages of this project and recognized my interest in the New Journalism. -

CS 201 569 Concept of New Journalism, This Study Also

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 677 CS 201 569 AUTHOR Murphy, James E. TITLE The New Journalism: A Critical Perspective. Journalism Monographs, No. 34. INZT/TUTION Association for Education in Journalism. PUB DATE May 74 MUTE 44p. !DRS PRICE MF-$0.75 MC-41.85 PLUS POSTAGE DTASCRIPTORS Definitions; Higher Education; *Journalism; Literary Conventions; *Literature Reviews; *Media Research; *New Journalism; *Newspapers; *News Reporting; Publishing-Industry ABSTRACT Addressing the question of the usefulness of the concept of New Journalism, this study also seeks to define the essential characteristics of New Journalism and to determine whether, in fact, there is such a thing. The first chapter reviews the critical literature of New Journalism, sorting outsome of the many uses of the term, then narrowing the focus to look at what some writers who call themselves (or are called) New Journalistssay they do and at what others say they do. The second chapterproposes a definition of New Journalism, states it conceptually, and exemplifies it operationally. The third chapter considerssome journalistic aspects of New Journalise and discusses the techniques--once the domain of fiction writers--which New Journalists have applied tonew reporting. The fourth and final chapter presents some conclusions. (RB) USDEPARTMENT Of HEALTH EDUCAT.ONI WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE Or EDUCATION - Ht EtiQFPRO I . = IrEE .ED r.e _% 1.' ON G N.' t M1 CII T NL(C.,,AN QEPRk ,E 1. C NA' 3NA,NI° 'ATE D C.4 POD C NO411.120. SOCOO journalism monographs NUMBER THIRTY-FOUR JAMES E. MURPHY The New Journalism: .1 Critical Perspective MAY 1974 Published serially since 1988 by the Association for Education in Jour- nalism. -

University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation.