CS 201 569 Concept of New Journalism, This Study Also

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mechanic the Secret World of the F1 Pitlane Marc 'Elvis' Priestley

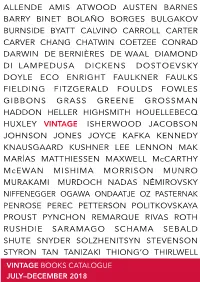

ALLENDE AMIS ATWOOD AUSTEN BARNES BARRY BINET BOLAÑO BORGES BULGAKOV BURNSIDE BYATT CALVINO CARROLL CARTER CARVER CHANG CHATWIN COETZEE CONRAD DARWIN DE BERNIÈRES DE WAAL DIAMOND DI LAMPEDUSA DICKENS DOSTOEVSKY DOYLE ECO ENRIGHT FAULKNER FAULKS FIELDING FITZGERALD FOULDS FOWLES GIBBONS GRASS GREENE GROSSMAN HADDON HELLER HIGHSMITH HOUELLEBECQ HUXLEY ISHERWOOD JACOBSON JOHNSON JONES JOYCE KAFKA KENNEDY KNAUSGAARD KUSHNER LEE LENNON MAK MARÍAS MATTHIESSEN MAXWELL McCARTHY McEWAN MISHIMA MORRISON MUNRO MURAKAMI MURDOCH NADAS NÉMIROVSKY NIFFENEGGER OGAWA ONDAATJE OZ PASTERNAK PENROSE PEREC PETTERSON POLITKOVSKAYA PROUST PYNCHON REMARQUE RIVAS ROTH RUSHDIE SARAMAGO SCHAMA SEBALD SHUTE SNYDER SOLZHENITSYN STEVENSON STYRON TAN TANIZAKI THIONG’O THIRLWELL TVINTAGEHORPE BOOKS THU CATALOGUEBRON TOLSTOY TREMAIN TJULY–DECEMBERYLER VARGAS 2018 VONNEGUT WARHOL WELSH WESLEY WHEELER WIGGINS WILLIAMS WINTERSON WOLFE WOOLF WYLD YATES ZOLA ALLENDE AMIS ATWOOD AUSTEN BARNES BARRY BINET BOLAÑO BORGES BULGAKOV BURNSIDE BYATT CALVINO CARROLL CARTER CARVER CHANG CHATWIN COETZEE CONRAD DARWIN DE BERNIÈRES DE WAAL DIAMOND DI LAMPEDUSA DICKENS DOSTOEVSKY DOYLE ECO ENRIGHT FAULKNER FAULKS FIELDING FITZGERALD FOULDS FOWLES GIBBONS GRASS GREENE GROSSMAN HADDON HELLER HIGHSMITH HOUELLEBECQ HUXLEY ISHERWOOD JACOBSON JOHNSON JONES JOYCE KAFKA KENNEDY KNAUSGAARD KUSHNER LEE LENNON MAK MARÍAS MATTHIESSEN MAXWELL McCARTHY McEWAN MISHIMA MORRISON MUNRO MURAKAMI MURDOCH NADAS NÉMIROVSKY NIFFENEGGER OGAWA ONDAATJE OZ PASTERNAK PENROSE PEREC PETTERSON POLITKOVSKAYA PROUST PYNCHON -

Joan Didion and the New Journalism

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Theses Digitization Project John M. Pfau Library 1986 Joan Didion and the new journalism Jean Gillingwators Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gillingwators, Jean, "Joan Didion and the new journalism" (1986). Theses Digitization Project. 417. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd-project/417 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the John M. Pfau Library at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses Digitization Project by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOAN DIDION AND THE NEW JOURNALISM A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in English Composition by Jean Gillingwators June 1986 JOAN DIDION AND THE NEW JOURNALISM ■ ■ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Jean ^i^ingwators June 1986 Approved by: Jw IT m Chair Date Abstract Most texts designed to teach writing include primarily non-fiction models. Most teachers, though, have been trained in the belles lettres tradition, and their competence usually lies with fiction Or poetry. Cultural preference has traditionally held that fiction is the most important form of literature. Analyzing a selection of twentieth century non-fiction prose is difficult; there are too few resources, and conventional analytical methods too often do not fit modern non-fiction. The new journalism, a recent literary genre, is especially difficult to "teach" because it blends fictive and journalistic techniques. -

Case Closed Or Evidence Ignored? John H. Davis

CASE CLOSED OR EVIDENCE IGNORED? JOHN H. DAVIS CASE CLOSED OR EVIDENCE IGNORED? Gerald Posner's book, CASE CLOSED - Lee Harvey Oswald and The Assassination of JFK, is essentially a lawyer's prosecutorial brief against Oswald as the lone, unaided assassin of President Kennedy, emphasizing the slender evidence for his sole guilt, and downplaying, even ignoring, the substantial body of evidence that suggests he might have had confederates. The book contains nothing new except a wildly implausible theory of the first shot fired at the presidential motorcade in Dealey Plaza. Essentially the book is a re-hash of a thirty-year-old discredited theory that repeats many of the failings of the Warren Commission's deeply flawed 1964 investigation. Along the way Mr. Posner is guilty of gross misstatements of fact and significant selective omission of crucial evidence. Mr. Posner's new theory of the first shot is perhaps the most implausible of any JFK assassination writer, including the wildest conspiracy theorists. Posner would have us believe that Lee Harvey Oswald's first shot was fired between Zapruder film frames 160 and 166 through the foliage of a tree and was deflected away from the presidential motorcade by a branch. Any marksman knows that his first shot at a target is always 2 his best shot because he has time to aim without the interference of having to operate the bolt in a hurry to load. Posner would have the marksman Oswald take his first shot through a thicket of tree branches and leaves when he couldn't clearly see his target. -

Directory of Seminars, Speakers, & Topics

Columbia University | THE UNIVERSITY SEMINARS 2016 2015DIRECTORY OF SEMINARS, SPEAKERS, & TOPICS Contents Introduction . 4 History of the University Seminars . 6 Annual Report . 8 Leonard Hastings Schoff Memorial Lectures Series . 10 Schoff and Warner Publication Awards . 13 Digital Archive Launch . 16 Tannenbaum-Warner Award and Lecture . .. 17 Book Launch and Reception: Plots . 21 2015–2016 Seminar Conferences: Women Mobilizing Memory: Collaboration and Co-Resistance . 22 Joseph Mitchell and the City: A Conversation with Thomas Kunkel And Gay Talese . 26 Alberto Burri: A Symposium at the Italian Academy of Columbia University . 27 “Doing” Shakespeare: The Plays in the Theatre . 28 The Politics of Memory: Victimization, Violence, and Contested Memories of the Past . 30 70TH Anniversary Conference on the History of the Seminar in the Renaissance . .. 40 Designing for Life And Death: Sustainable Disposition and Spaces Of Rememberance in the 21ST Century Metropolis . 41 Calling All Content Providers: Authors in the Brave New Worlds of Scholarly Communication . 46 104TH Meeting of the Society of Experimental Psychologists . 47 From Ebola to Zika: Difficulties of Present and Emerging Infectious Diseases . 50 The Quantitative Eighteenth Century: A Symposium . 51 Appetitive Behavior Festchrift: A Symposium Honoring Tony Sclafani and Karen Ackroff . 52 Indigenous Peoples’ Rights and Unreported Struggles: Conflict and Peace . 55 The Power to Move . 59 2015– 2016 Seminars . 60 Index of Seminars . 160 Directory of Seminars, Speakers, & Topics 2015–2016 3 ADVISORY COMMITTEE 2015–2016 Robert E. Remez, Chair Professor of Psychology, Barnard College George Andreopoulos Professor, Political Science and Criminal Justice CUNY Graduate School and University Center Susan Boynton Professor of Music, Columbia University Jennifer Crewe President and Director, Columbia University Press Kenneth T. -

Dr J. Oliver Boyd-Barrett (2009)

Dr J. Oliver Boyd-Barrett (2009) 1 Oliver Boyd-Barrett Full Resume Education (Higher Education) Ph.D . (1978) From the Open University (U.K.). World wide news agencies: Development, organization, competition, markets and product. A study of Agence France Presse, Associated Press, Reuters and United Press to 1975. (UMI Mircofiche Author No.4DB 5008). BA Hons , (Class 2i) (1967). From Exeter University (U.K.). Sociology. (High School) GCE (General Certificate of Education)(U.K.): 'A' levels in History (Grade A), English Literature (Grade A), 'Special' paper in History (Grade 1), and Latin (AO), 1964; ‘0’ levels: passes in 10 subjects, including three ‘A’ grades; studied at Salesian College, Chertsey, Surrey (U.K.). Appointments and Experience (1) Full-time Appointments 2008- Professor (full), Department of Journalism, School of Communication Studies, Bowling Green State University, Ohio 2005-2008: Director, School of Communication Studies, Bowling Green State University, Ohio. 2001 - 2005: Full professor, tenured, Department of Communication in College of Letters, Arts and Social Sciences, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona (U.S.A.). 1998-2001: Associate Dean of the College of the Extended University, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona (U.S.A.). 1994-98: Director, Distance Learning, at the Centre for Mass Communications Research, Leicester University, and Director of the MA in Mass Communication (by distance learning) (U.K.). 1990-94: Sub-Dean (Courses) and Senior Lecturer, School of Education, at the Open University; Deputy Director MA in Education, 1992-3. (U.K.). 1985-90: Lecturer, School of Education, at the Open University (Language and Communications) (U.K.). 1975-85: Lecturer, School of Education, at the Open University (Administration and Management) (U.K.). -

Che Utifee Chronicle

Che Utifee Chronicle Volume 65 Number 23 Durham, North Carolina Thursday, October 16, 1969 Students, faculty appeal for peace Newfield urges Mobe activities 'street-vote'stand draw thousands By David Pace By Andy Parker Executive News Editor Policy Editor Jack Newfield, Assistant Editor of the "Village Voice," Over 2000 members of the Duke community told over 1000 students last night in Page Auditorium that participated yesterday in a "moratorium on business as a new movement must be formed "to commit ourselves to usual" as part of a nationwide protest against the war in voting with our feet in the streets until this war is over." Vietnam. Sponsored by the University Union Major Speakers Dub Gulley, chairman of the Duke Mobilization Committee and the Mobilization Committee, Newfield Committee said "today's response has shown that the issue proposed that the new movement could offer a 1972 of Vietnam transcends the divisions within the University presidential candidate "whose name is not as important as community." his platform, and whose party may not even now be "The time for discussion was today." Now we must put formed." our thoughts into action," he continued, asking for support He emphasized that "despite Lyndon Johnson's and participation in the November 14-15 marches in abdication and Richard Nixon's inauguration, American Washington. and Vietnamese men are still dying." In order to bring Gulley said he was looking for "as many as 1000 people about an end to the war, Newfield proposed a "national from the Duke community" to travel to the Capital to income tax strike for next April 15," in which taxes would "demonstrate to our President that the war must end...by be put in the banks and given to the government only on giey total immediate withdrawal of all American troops from the condition that the Vietnam war was ended. -

The Leadership Institute's Broadcast Journalism School

“They may teach you a lot in college, but the polishing tips you learn here are just Launch your broadcast the edge you need to get the journalism career job you want.” - Ashley Freer Lawrenceville, GA The Leadership Institute’s Broadcast Journalism School Balance the media -- be the media -- get a job in broadcast journalism If you’re a conservative student interested in a career in journalism, the Leadership Institute’s Broadcast Journalism School is for you. The BJS is an intense, two-day seminar that gives aspiring conservative journalists the skills necessary to bring balance to the media and succeed in this highly competitive field. Learn: l How to prepare a winning résumé tape l How to plan a successful step-by-step job hunt l The nuts-and-bolts of building a successful broadcasting career Thanks to these techniques, close to 100 BJS grads now have full-time jobs in TV news. To register visit www.leadershipinstitute.org or call 1-800-827-5323 Start your future today Get paid $3,000 during your unpaid internship! Register Today! Graduates of the Leadership Institute’s Broadcast Journalism School now have a new way to 2007 Training Sessions build a successful media career: The Balance in Media Fellowship March 31 - April 1 A Balance in Media Fellowship could help you afford an unpaid internship – whether Arlington, VA you’re interning at your local television station or for a national news network. July 31- July 22 With a Balance in Media Fellowship, you can: Arlington, VA l Receive up to $3,000 during your three-month internship l Gain real-life experience at your media internship October 27 - October 28 l Start your career as a conservative journalist Arlington, VA Just send in your application, and you could have up to $3,000 for your unpaid internship! For details and an application, call the Leadership Institute at (800) 827-5323. -

Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J

Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J. Keith Saliba, Ted Geltner Journal of Magazine Media, Volume 13, Number 2, Summer 2012, (Article) Published by University of Nebraska Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jmm.2012.0002 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/773721/summary [ Access provided at 1 Oct 2021 07:15 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] Literary War Journalism Literary War Journalism: Framing and the Creation of Meaning J. Keith Saliba, Jacksonville University [email protected] Ted Geltner, Valdosta State University [email protected] Abstract Relatively few studies have systematically analyzed the ways literary journalists construct meaning within their narratives. This article employed rhetorical framing analysis to discover embedded meaning within the text of John Sack’s Gulf War Esquire articles. Analysis revealed several dominant frames that in turn helped construct an overarching master narrative—the “takeaway,” to use a journalistic term. The study concludes that Sack’s literary approach to war reportage helped create meaning for readers and acted as a valuable supplement to conventional coverage of the war. Keywords: Desert Storm, Esquire, framing, John Sack, literary journalism, war reporting Introduction Everything in war is very simple, but the simplest thing is difficult. The difficulties accumulate and end by producing a kind of friction that is inconceivable unless one has experienced war. —Carl von Clausewitz Long before such present-day literary journalists as Rolling Stone’s Evan Wright penned Generation Kill (2004) and Chris Ayres of the London Times gave us 2005’s War Reporting for Cowards—their poignant, gritty, and sometimes hilarious tales of embedded life with U.S. -

A Cinema of Confrontation

A CINEMA OF CONFRONTATION: USING A MATERIAL-SEMIOTIC APPROACH TO BETTER ACCOUNT FOR THE HISTORY AND THEORIZATION OF 1970S INDEPENDENT AMERICAN HORROR _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by COURT MONTGOMERY Dr. Nancy West, Thesis Supervisor DECEMBER 2015 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled A CINEMA OF CONFRONTATION: USING A MATERIAL-SEMIOTIC APPROACH TO BETTER ACCOUNT FOR THE HISTORY AND THEORIZATION OF 1970S INDEPENDENT AMERICAN HORROR presented by Court Montgomery, a candidate for the degree of master of English, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _________________________________ Professor Nancy West _________________________________ Professor Joanna Hearne _________________________________ Professor Roger F. Cook ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest appreciation to my committee chair, Dr. Nancy West, for her endless enthusiasm, continued encouragement, and excellent feedback throughout the drafting process and beyond. The final version of this thesis and my defense of it were made possible by Dr. West’s critique. I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Joanna Hearne and Dr. Roger F. Cook, for their insights and thought-provoking questions and comments during my thesis defense. That experience renewed my appreciation for the ongoing conversations between scholars and how such conversations can lead to novel insights and new directions in research. In addition, I would like to thank Victoria Thorp, the Graduate Studies Secretary for the Department of English, for her invaluable assistance with navigating the administrative process of my thesis writing and defense, as well as Dr. -

University Microfilms International 300 N

THE CRITICISM OF ROBERT FRANK'S "THE AMERICANS" Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Alexander, Stuart Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 11:13:03 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/277059 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. -

In Cold Blood Unbroken

2020 RISING 11TH GRADE AP ENGLISH LANGUAGE SUMMER READING Students should read two books. Assessments will occur within the first two weeks of class and may include discussions, writing assignments, presentations, and/or tests. • These books are available in affordable paperbacks, online, or in local libraries. • Be sure the title and author match the assigned book and you are reading an unabridged edition. • If published with additional texts or stories, only read the assigned title. • These titles are taken from recommended reading lists for AP English exams and college- bound students. It is your responsibility to view all of these reading materials within a Christian perspective. While holding firm to your own beliefs, consider how any controversial elements reflect the flawed, sinful circumstances of separation from God and faith. #1 Required Book for all AP English Language Students: In Cold Blood by Truman Capote "Until one morning in mid-November of 1959, few Americans--in fact, few Kansans--had ever heard of Holcomb. Like the waters of the river, like the motorists on the highway, and like the yellow trains streaking down the Santa Fe tracks, drama, in the shape of exceptional happenings, had never stopped there." If all Truman Capote did was invent a new genre-— journalism written with the language and structure of literature-—this "nonfiction novel" about the brutal slaying of the Clutter family by two would-be robbers would be remembered as a trail-blazing experiment that has influenced countless writers. But Capote achieved more than that. He wrote a true masterpiece of creative nonfiction. #2 Required Book for all AP English Language Students: Unbroken by Laura Hillenbrand (Amazon.com description) On a May afternoon in 1943, an American military plane crashed into the Pacific Ocean and disappeared, leaving only a spray of debris and a slick of oil, gasoline, and blood. -

Naturalism, the New Journalism, and the Tradition of the Modern American Fact-Based Homicide Novel

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. U·M·I University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml48106-1346 USA 3131761-4700 800!521-0600 Order Number 9406702 Naturalism, the new journalism, and the tradition of the modern American fact-based homicide novel Whited, Lana Ann, Ph.D.