Labyrinths by Jorge Luis Borges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dearth and Duality: Borges' Female Fictional Characters

DEARTH AND DUALITY: BORGES' FEMALE FICTIONAL CHARACTERS When studying Borges' fiction, the reader is immediately struck by the dear_th of female characters or love interest. Borges, who has often been questioned about this aspect of his work confided to Gloria Alcorta years ago: "alors si je n 'ecris pas sur ses sujects, c 'est simplememnt par·pudeur ... sans doute ai-je-ete trop ocupe par l'amour dans rna vie privee pour en parler dans roes livres."1 At the age of eighty, when questioned by Coffa, Borges said: "If I have created any character, I don't think so, I am always writing about myself ... It is always the same old Borges, only slightly disguised. "2 Many critics have decried lack of female characters and character development. Alicia Jurado likens Borges to a stage director who uses women as one would furniture or sets, in order to create environment. She says:" son borrosos o casuales o lo minimo indiferenciadas y pasi vas. "3 E.D. Carter calls Borges' women little more than abstractions or symbolic interpretations.4 Picknhayn says that Borges' women "aparecen distorsionadas ... hasta el punto de transformar cada mujer en una cosa amorfa y carente de personalidad. " 5 and Lloyd King feels that the women of Borges' stories "always at best seem instrumental. "6 All of the above can be said of most of his male characters because none of Borges' characters can be classified in the traditional sense. A Vilari or Hladik is no more real than a Beatriz or Ulrica. Juan Otalora is no more real than la Pelirroja and Red Scharlach is no more real than Emma Zunz. -

Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the Writings of Jorge Luis Borges

Kevin Wilson Of Stones and Tigers; Time, Infinity, Recursion, and Liminality in the writings of Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986) and Pu Songling (1640-1715) (draft) The need to meet stones with tigers speaks to a subtlety, and to an experience, unique to literary and conceptual analysis. Perhaps the meeting appears as much natural, even familiar, as it does curious or unexpected, and the same might be said of meeting Pu Songling (1640-1715) with Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), a dialogue that reveals itself as much in these authors’ shared artistic and ideational concerns as in historical incident, most notably Borges’ interest in and attested admiration for Pu’s work. To speak of stones and tigers in these authors’ works is to trace interwoven contrapuntal (i.e., fugal) themes central to their composition, in particular the mutually constitutive themes of time, infinity, dreaming, recursion, literature, and liminality. To engage with these themes, let alone analyze them, presupposes, incredibly, a certain arcane facility in navigating the conceptual folds of infinity, in conceiving a space that appears, impossibly, at once both inconceivable and also quintessentially conceptual. Given, then, the difficulties at hand, let the following notes, this solitary episode in tracing the endlessly perplexing contrapuntal forms that life and life-like substances embody, double as a practical exercise in developing and strengthening dynamic “methodologies of the infinite.” The combination, broadly conceived, of stones and tigers figures prominently in -

Dragonlore Issue 37 08-11-03

The bird was a Rukh and the white dome, of course, was its egg. Sindbad lashes himself to the bird’s leg with his turban, and the next morning is whisked off into flight and set down on a mountaintop, without having excited the Rukh’s attention. The narrator adds that the Rukh feeds itself on serpents of such great bulk that they would have made but one gulp of an elephant. In Marco Polo’s Travels (III, 36) we read: Dragonlore The people of the island [of Madagascar] report that at a certain season of the year, an extraordinary kind of bird, which they call a rukh, makes its appearance from The Journal of The College of Dracology the southern region. In form it is said to resemble the eagle but it is incomparably greater in size; being so large and strong as to seize an elephant with its talons, and to lift it into the air, from whence it lets it fall to the ground, in order that when dead it Number 37 Michaelmas 2003 may prey upon the carcase. Persons who have seen this bird assert that when the wings are spread they measure sixteen paces in extent, from point to point; and that the feathers are eight paces in length, and thick in proportion. Marco Polo adds that some envoys from China brought the feather of a Rukh back to the Grand Kahn. A Persian illustration in Lane shows the Rukh bearing off three elephants in beak and talons; ‘with the proportion of a hawk and field mice’, Burton notes. -

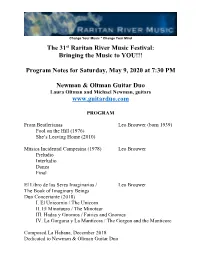

Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman

Change Your Music * Change Your Mind The 31st Raritan River Music Festival: Bringing the Music to YOU!!! Program Notes for Saturday, May 9, 2020 at 7:30 PM Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Laura Oltman and Michael Newman, guitars www.guitarduo.com PROGRAM From Beatlerianas Leo Brouwer (born 1939) Fool on the Hill (1976) She’s Leaving Home (2010) Música Incidental Campesina (1978) Leo Brouwer Preludio Interludio Danza Final El Libro de los Seres Imaginarios / Leo Brouwer The Book of Imaginary Beings Duo Concertante (2018) I. El Unicornio / The Unicorn II. El Minotauro / The Minotaur III. Hadas y Gnomos / Fairies and Gnomes IV. La Gorgona y La Mantícora / The Gorgon and the Manticore Composed La Habana, December 2018 Dedicated to Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo Commissioned by Raritan River Music With the generous support of Jeffrey Nissim CYBERSPACE PERMIERE PERFORMANCE Composed in celebration of the 80th Anniversary Year of Leo Brouwer NOTES IN ENGLISH CAPTURING THE IMAGINARY BEINGS BY LAURA OLTMAN AND MICHAEL NEWMAN The guitar explosion in the United States in the 1960s was fueled by the influence of Cuban musicians, including the legendary Leo Brouwer, as well as Juan Mercadal, Elías Barreiro, Mario Abril, and our teachers Alberto Valdes Blain and Luisa Sánchez de Fuentes. We grew up playing the music of Leo Brouwer. In the early days of the Newman & Oltman Guitar Duo, we shared a booking agent with Brouwer, Sheldon Soffer Management. We often thought that a major duet by Maestro Brouwer would be a dream for our duo. We met Brouwer at his New York debut recital in 1978, which was co- sponsored by Americas Society. -

In “Death and the Compass” Borges Presciently Anticipates De

SYMMETRY OF DEATH w Adrian Gargett n “Death and the Compass” Borges presciently anticipates de- velopments in contemporary physics and scientific thought, I constructing a literary environment that systemically gives the lie t o the dream of rational determinism, suggesting instead some- thing like a “primordial disorder” out of which the shifting, provi- sional orders of culture and science emerge. In constructing a subtle and complex argument via the parallel in- teractions of a Deleuzo-guattarian mechanism, this project artfully attempts to weave the principal discursive strands into an animated investigative framework. The first strand is a close analysis of sections from “Death and the Compass”. The second is the articulation of the critical concepts from the Deleuzo-guattarian scheme. The third is the embedding of the issues of chance and causality within the work of Borges. J (NORTH) The first murder occurred in the Hotel du Nord – that tall prism which dominates the estuary whose waters are the colour of the de- sert. To that tower (which quite glaringly unifies the hateful white- ness of a hospital, the numbered divisibility of a jail and the general Variaciones Borges 13 (2002) 80 ADRIAN GARGETT appearance of a bordello) there came on the third day of December the delegate from Podolsk to the Third Talmudic Congress, Doctor Marcel Yarmolinsky, a grey-bearded man with grey eyes. (Labyrinths 106) Deleuze and Guattari cast literature as an exemplary mode to demonstrate systems of machinic functioning; how litera- ture/books/writing operates in terms of such functioning – in terms of a “rhizomatic” analysis as presented in “A Thousand Plateaus”.1 Deleuze and Guattari’s rhizomatic conceptual vehicle maps a schizoanalytic application to Borges disseminating literary texts. -

Digilenguas N7

Autoridades U.N.C. Rectora Dra. Carolina Scotto Vicerrectora 2011 Dra. Hebe Goldenhersch Revista DIGILENGUAS Facultad de Lenguas Autoridades Facultad Universidad Nacional de Córdoba de Lenguas Decana ISSN 1852-3935 Dra. Silvia Barei URL: http://www.lenguas.unc.edu.ar/Digi/ Vicedecana Mgtr. Griselda Bombelli Av. Valparaíso s/n, Ciudad Universitaria, Córdoba C.P. X5000- Argentina. Departamento Editorial Facultad de Lenguas TELÉFONOS: 054-351-4331073/74/75 Coordinador Fax: 054-351-4331073/74/75 Dr. Roberto Oscar Páez E-MAIL: [email protected] Desarrollo web, diseño y edición Mgtr. Sergio Di Carlo Consejo Editorial Mgtr. Hebe Gargiulo Esp. Ana Goenaga Lic. Ana Maccioni Lic. Liliana Tozzi Prof. Richard Brunel Revista DIGILENGUAS n.º 7 – Abril de 2011 Departamento Editorial - Facultad de Lenguas Universidad Nacional de Córdoba Contenido PRESENTACIÓN .................................................................................................................................. 3 INTRODUCCIÓN .................................................................................................................................. 4 CONFERENCIAS PLENARIAS .............................................................................................. 5 Silvia Noemí Barei .............................................................................................................................. 6 Sistemas de paso: la Red Borges ........................................................................................................... 6 Ana María -

Abismo Logico.Pdf

Otros títulos de esta Colección EL ABISMO LÓGICO MANUEL BOTERO CAMACHO Este libro explora un fenómeno que se mencionar filósofos y escribir cuentos (BORGES Y LOS FFFEILOSOFEOS F DE LAS IDEAS) Doctor en Filología de la Universidad Complu- repite en algunos textos del escritor argen- acerca de una realidad imposible tense de Madrid con Diploma de Estudios Avan- tino Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986). Está siguiendo sus filosofías, de mostrar algo MANUEL BOTERO CAMACHO GÉNESIS Y TRANSFORMACIONES MANUEL BOTERO CAMACHO zados en Filología Inglesa y en Filología Hispa- DEL ESTADO NACIÓN EN COLOMBIA compuesto por nueve capítulos, que acerca de sus creencias, sería precisa- noamericana. Licenciado en Literatura, opción UNA MIRADA TOPOLÓGICA A LOS ESTUDIOS SOCIALES DESDE LA FILOSOFÍA POLÍTICA corresponden al análisis de la reescritura mente su escepticismo respecto de en filosofía, de la Universidad de Los Andes, de nueve distintas propuestas filosóficas. dichas doctrinas. Los relatos no suponen Bogotá. Es profesor en la Escuela de Ciencias ADOLFO CHAPARRO AMAYA Las propuestas están cobijadas bajo la su visión de la realidad sino una lectura Humanas y en la Facultad de Jurisprudencia CAROLINA GALINDO HERNÁNDEZ misma doctrina: el idealismo. Es un libro de las teorías acerca de la realidad. (Educación Continuada) del Colegio Mayor de que se escribe para validar la propuesta Nuestra Señora del Rosario. Es profesor de de un método de lectura que cuenta a la El texto propone análisis novedosos de Semiología y Coordinador de los Conversato- COLECCIÓN TEXTOS DE CIENCIAS HUMANAS vez con una dosis de ingenio y con los cuentos de Borges y reevalúa y rios de la Casa Lleras en la Universidad Jorge planteamientos rigurosos, permitiendo critica algunos análisis existentes elabo- Tadeo Lozano. -

Ge Fei's Creative Use of Jorge Luis Borges's Narrative Labyrinth

Fudan J. Hum. Soc. Sci. DOI 10.1007/s40647-015-0083-x ORIGINAL PAPER Imitation and Transgression: Ge Fei’s Creative Use of Jorge Luis Borges’s Narrative Labyrinth Qingxin Lin1 Received: 13 November 2014 / Accepted: 11 May 2015 © Fudan University 2015 Abstract This paper attempts to trace the influence of Jorge Luis Borges on Ge Fei. It shows that Ge Fei’s stories share Borges’s narrative form though they do not have the same philosophical premises as Borges’s to support them. What underlies Borges’s narrative complexity is his notion of the inaccessibility of reality or di- vinity and his understanding of the human intellectual history as epistemological metaphors. While Borges’s creation of narrative gap coincides with his intention of demonstrating the impossibility of the pursuit of knowledge and order, Ge Fei borrows this narrative technique from Borges to facilitate the inclusion of multiple motives and subject matters in one single story, which denotes various possible directions in which history, as well as story, may go. Borges prefers the Jungian concept of archetypal human actions and deeds, whereas Ge Fei tends to use the Freudian psychoanalysis to explore the laws governing human behaviors. But there is a perceivable connection between Ge Fei’s rejection of linear history and tradi- tional storyline with Borges’ explication of epistemological uncertainty, hence the former’s tremendous debt to the latter. Both writers have found the conventional narrative mode, which emphasizes the telling of a coherent story having a begin- ning, a middle, and an end, inadequate to convey their respective ideational intents. -

1 Jorge Luis Borges the GOSPEL ACCORDING to MARK

1 Jorge Luis Borges THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO MARK (1970) Translated by Norrnan Thomas di Giovanni in collaboration with the author Jorge Luis Borges (1899-1986), an outstanding modern writer of Latin America, was born in Buenos Aires into a family prominent in Argentine history. Borges grew up bilingual, learning English from his English grandmother and receiving his early education from an English tutor. Caught in Europe by the outbreak of World War II, Borges lived in Switzerland and later Spain, where he joined the Ultraists, a group of experimental poets who renounced realism. On returning to Argentina, he edited a poetry magazine printed in the form of a poster and affixed to city walls. For his opposition to the regime of Colonel Juan Peron, Borges was forced to resign his post as a librarian and was mockingly offered a job as a chicken inspector. In 1955, after Peron was deposed, Borges became director of the national library and Professor of English Literature at the University of Buenos Aires. Since childhood a sufferer from poor eyesight, Borges eventually went blind. His eye problems may have encouraged him to work mainly in short, highly crafed forms: stories, essays, fables, and lyric poems full of elaborate music. His short stories, in Ficciones (1944), El hacedor (1960); translated as Dreamtigers, (1964), and Labyrinths (1962), have been admired worldwide. These events took place at La Colorada ranch, in the southern part of the township of Junin, during the last days of March 1928. The protagonist was a medical student named Baltasar Espinosa. We may describe him, for now, as one of the common run of young men from Buenos Aires, with nothing more noteworthy about him than an almost unlimited kindness and a capacity for public speaking that had earned him several prizes at the English school0 in Ramos Mejia. -

Postmodern Or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation

Edna Aizenberg Postmodern or Post-Auschwitz Borges and the Limits of Representation he list of “firsts” is well known by now: Borges, father of the New Novel, the nouveau roman, the Boom; Borges, forerunner T of the hypertext, early magical realist, proto-deconstructionist, postmodernist pioneer. The list is well known, but it may omit the most significant encomium: Borges, founder of literature after Auschwitz, a literature that challenges our orders of knowledge through the frac- tured mirror of one of the century’s defining events. Fashions and prejudices ingrained in several critical communities have obscured Borges’s role as a passionate precursor of many later intellec- tuals -from Weisel to Blanchot, from Amery to Lyotard. This omission has hindered Borges research, preventing it from contributing to major theoretical currents and areas of inquiry. My aim is to confront this lack. I want to rub Borges and the Holocaust together in order to unset- tle critical verities, meditate on the limits of representation, foster dia- logue between disciplines -and perhaps make a few sparks fly. A shaper of the contemporary imagination, Borges serves as a touch- stone for concepts of literary reality and unreality, for problems of knowledge and representation, for critical and philosophical debates on totalizing systems and postmodern esthetics, for discussions on cen- ters and peripheries, colonialism and postcolonialism. Investigating the Holocaust in Borges can advance our broadest thinking on these ques- tions, and at the same time strengthen specific disciplines, most par- ticularly Borges scholarship, Holocaust studies, and Latin American literary criticism. It is to these disciplines that I now turn. -

Actualización Bibliográfica De Obras Sobre JL Borges (1985-1998)

MUÑOZ RENGEL , J.J., revista Estigma nº 3 (1999), pp. 86-109. Actualización bibliográfica de obras sobre J. L. Borges (1985-1998) Juan Jacinto Muñoz Rengel Cualquier estudioso o apasionado de Borges conoce la amplitud y dispersión de su obra –relatos, ensayos, reseñas, poemas, prólogos, conferencias– y lo ingente de la bibliografía que crece en torno al escritor. Para no perderse en este océano puede hacer uso de los siguientes cuadernos de bitácora: BARRENECHEA, A.Mª., “Bibliografía”, en La expresión de la irrealidad en la obra de Borges , México, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1957. BASTOS, Mª.,L., Borges ante la crítica argentina 1923-1960 , Buenos Aires, Ed. Hispanoamericana, 1974. BECCO, H.J., Jorge Luis Borges, Bibliografía total 1923-1973 , Buenos Aires, Casa Pardo, 1973. CERVERA, V., “Bibliografía”, en La poesía de Jorge Luis Borges: historia de una eternidad , Murcia, Secretariado de Publicaciones de la Universidad, 1992, pp. 219-243. GILARDONI, J., Borgesiana. Catálogo bibliográfico de Jorge Luis Borges 1923-1983 , Buenos Aires, Catedral al Sur, 1989. FOSTER, D.W., A Bibliography of the works of Jorge Luis Borges , Arizona, Center for Latin American Press University, 1971. –––––, Jorge Luis Borges: an annotated primary and secundary bibliography , NewYork–London, Garland Publishing Inc., 1984. HELFT, N., Bibliografía completa , Buenos Aires, F.C.E., 1997. LOEWENSTEIN, C. J., A descriptive catalogue of the Jorge Luis Borges Collection at the University of Virginia Library , Charlottesville, London, University Press of Virginia, 1993. LOUIS, A.; ZICHE, F., Bibliographie de l'œuvre de Jorge Luis Borges 1919-1960 (inédito). NODIER L.; REVELLO, L. (comp.), Bibliografía argentina de Artes y Letras , número especial de Contribución a la bibliografía argentina de Jorge Luis Borges , Buenos Aires, Fondo Nacional de las Artes, abril-septiembre de 1961. -

Hyper Memory, Synaesthesia, Savants Luria and Borges Revisited

Dement Neuropsychol 2018 June;12(2):101-104 Views & Reviews http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1980-57642018dn12-020001 Hyper memory, synaesthesia, savants Luria and Borges revisited Luis Fornazzari1, Melissa Leggieri2, Tom A. Schweizer3, Raul L. Arizaga4, Ricardo F. Allegri5, Corinne E. Fischer6 ABSTRACT. In this paper, we investigated two subjects with superior memory, or hyper memory: Solomon Shereshevsky, who was followed clinically for years by A. R. Luria, and Funes the Memorious, a fictional character created by J. L. Borges. The subjects possessed hyper memory, synaesthesia and symptoms of what we now call autistic spectrum disorder (ASD). We will discuss interactions of these characteristics and their possible role in hyper memory. Our study suggests that the hyper memory in our synaesthetes may have been due to their ASD-savant syndrome characteristics. However, this talent was markedly diminished by their severe deficit in categorization, abstraction and metaphorical functions. As investigated by previous studies, we suggest that there is altered connectivity between the medial temporal lobe and its connections to the prefrontal cingulate and amygdala, either due to lack of specific neurons or to a more general neuronal dysfunction. Key words: memory, hyper memory, savantism, synaesthesia, autistic spectrum disorder, Solomon Shereshevsky, Funes the memorious. HIPERMEMÓRIA, SINESTESIA, SAVANTS: LURIA E BORGES REVISITADOS RESUMO. Neste artigo, investigamos dois sujeitos com memória superior ou hipermemória: Solomon Shereshevsky, que foi seguido clinicamente por anos por A. R. Luria, e Funes o memorioso, um personagem fictício criado por J. L. Borges. Os sujeitos possuem hipermemória, sinestesia e sintomas do que hoje chamamos de transtorno do espectro autista (TEA).