Popular Participation in the Constitution of the Illiberal State--An

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1

Bjarkman Bibliography| March 2014 1 PETER C. BJARKMAN www.bjarkman.com Cuban Baseball Historian Author and Internet Journalist Post Office Box 2199 West Lafayette, IN 47996-2199 USA IPhone Cellular 1.765.491.8351 Email [email protected] Business phone 1.765.449.4221 Appeared in “No Reservations Cuba” (Travel Channel, first aired July 11, 2011) with celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain Featured in WALL STREET JOURNAL (11-09-2010) front page story “This Yanqui is Welcome in Cuba’s Locker Room” PERSONAL/BIOGRAPHICAL DATA Born: May 19, 1941 (72 years old), Hartford, Connecticut USA Terminal Degree: Ph.D. (University of Florida, 1976, Linguistics) Graduate Degrees: M.A. (Trinity College, 1972, English); M.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1970, Education) Undergraduate Degree: B.S.Ed. (University of Hartford, 1963, Education) Languages: English and Spanish (Bilingual), some basic Italian, study of Japanese Extensive International Travel: Cuba (more than 40 visits), Croatia /Yugoslavia (20-plus visits), Netherlands, Italy, Panama, Spain, Austria, Germany, Poland, Czech Republic, France, Hungary, Mexico, Ecuador, Colombia, Guatemala, Canada, Japan. Married: Ronnie B. Wilbur, Professor of Linguistics, Purdue University (1985) BIBLIOGRAPHY March 2014 MAJOR WRITING AWARDS 2008 Winner – SABR Latino Committee Eduardo Valero Memorial Award (for “Best Article of 2008” in La Prensa, newsletter of the SABR Latino Baseball Research Committee) 2007 Recipient – Robert Peterson Recognition Award by SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee, for advancing public awareness -

Cuba and the World.Book

CUBA FUTURES: CUBA AND THE WORLD Edited by M. Font Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies Presented at the international symposium “Cuba Futures: Past and Present,” organized by the The Cuba Project Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies The Graduate Center/CUNY, March 31–April 2, 2011 CUBA FUTURES: CUBA AND THE WORLD Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies www.cubasymposium.org www.bildner.org Table of Contents Preface v Cuba: Definiendo estrategias de política exterior en un mundo cambiante (2001- 2011) Carlos Alzugaray Treto 1 Opening the Door to Cuba by Reinventing Guantánamo: Creating a Cuba-US Bio- fuel Production Capability in Guantánamo J.R. Paron and Maria Aristigueta 47 Habana-Miami: puentes sobre aguas turbulentas Alfredo Prieto 93 From Dreaming in Havana to Gambling in Las Vegas: The Evolution of Cuban Diasporic Culture Eliana Rivero 123 Remembering the Cuban Revolution: North Americans in Cuba in the 1960s David Strug 161 Cuba's Export of Revolution: Guerilla Uprisings and Their Detractors Jonathan C. Brown 177 Preface The dynamics of contemporary Cuba—the politics, culture, economy, and the people—were the focus of the three-day international symposium, Cuba Futures: Past and Present (organized by the Bildner Center at The Graduate Center, CUNY). As one of the largest and most dynamic conferences on Cuba to date, the Cuba Futures symposium drew the attention of specialists from all parts of the world. Nearly 600 individuals attended the 57 panels and plenary sessions over the course of three days. Over 240 panelists from the US, Cuba, Britain, Spain, Germany, France, Canada, and other countries combined perspectives from various fields including social sciences, economics, arts and humanities. -

Trading with the Enemy: Opening the Door to U.S. Investment in Cuba

ARTICLES TRADING WITH THE ENEMY: OPENING THE DOOR TO U.S. INVESTMENT IN CUBA KEVIN J. FANDL* ABSTRACT U.S. economic sanctions on Cuba have been in place for nearly seven deca- des. The stated intent of those sanctionsÐto restore democracy and freedom to CubaÐis still used as a justi®cation for maintaining harsh restrictions, despite the fact that the Castro regime remains in power with widespread Cuban public support. Starving the Cuban people of economic opportunities under the shadow of sanctions has signi®cantly limited entrepreneurship and economic development on the island, despite a highly educated and motivated popula- tion. The would-be political reformers and leaders on the island emigrate, thanks to generous U.S. immigration policies toward Cubans, leaving behind the Castro regime and its ardent supporters. Real change on the island will come only if the United States allows Cuba to restart its economic engine and reengage with global markets. Though not a guarantee of political reform, eco- nomic development is correlated with demand for political change, giving the economic development approach more potential than failed economic sanctions. In this short paper, I argue that Cuba has survived in spite of the U.S. eco- nomic embargo and that dismantling the embargo in favor of open trade poli- cies would improve the likelihood of Cuba becoming a market-friendly communist country like China. I present the avenues available today for trade with Cuba under the shadow of the economic embargo, and I argue that real po- litical change will require a leap of faith by the United States through removal of the embargo and support for Cuba's economic development. -

Religion, Science Fiction, and Postmodernism in Neon Genesis Evangelion

Nikolai Afanasov The Depressed Messiah: Religion, Science Fiction, and Postmodernism in Neon Genesis Evangelion Translation by Markian Dobczansky DOI: https://doi.org/10.22394/2311-3448-2020-7-1-47-66 Nikolai Afanasov — Institute of Philosophy, Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow, Russia). [email protected] The article explores the anime series “Neon Genesis Evangelion” (1995–1996). The work is considered as a cultural product that is within the science fiction tradition of the second half of the twenti- eth century. The article shows how the series weaves together ele- ments of Shinto and Abrahamic religious traditions as equally rel- evant. Through the use of religious topics, the science fiction work acquires an inner cognitive logic. The religious in the series is repre- sented on two levels: an implicit one that defines the plot’s originality, and also an explicit one, in which references to religious matters be- come a marketing tool aimed at Japanese and Western media mar- kets. To grasp the sometimes controversial and incoherent religious symbols, the author proposes to use a postsecular framework of anal- ysis and the elements of a postmodern philosophy of culture. The au- thor then proposes an analysis of the show’s narrative using the reli- gious theme of apocalypse. Keywords: postsecularism, postmodern, Neon Genesis Evangelion, Shinto, Christianity, anime, science fiction, popular culture. Introduction MONG the many hallmarks that define mass culture are its uni- versality and versatility (Iglton 2019, 177). National cultural in- Adustries, which orient themselves toward an audience with spe- cific requirements, seldom become globally popular. The fortunes of Japanese popular culture1 at the end of the twentieth century, howev- 1. -

New Castro Same Cuba

New Castro, Same Cuba Political Prisoners in the Post-Fidel Era Copyright © 2009 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-562-8 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2009 1-56432-562-8 New Castro, Same Cuba Political Prisoners in the Post-Fidel Era I. Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations ....................................................................................................................... 7 II. Illustrative Cases ......................................................................................................................... 11 Ramón Velásquez -

Editor's Note

www.cubanews.com ISSN 1073-7715 Volume 6 Number 10 THE MIAMI HERALD PUBLISHING COMPANY October 1998 Editor's Note MAJOR DEVELOPMENTS Hurricane Georges Impact Food Supply Shrinks There has always been an Alice in Wonderland quality to developments in Already reeling from a drought, Cuba got Meanwhile, the combined effect of natural Cuba, but a series of recent develop- hit by another catastrophe in the form of disasters, market fluctuations and such ments seems particularly bizarre and Hurricane Georges. The disaster didn’t stop could have a devastating impact on the rich in irony. Fidel Castro from suggesting that Cuba’s already eroded living standards of Cubans. Take, for example, Fidel Castro’s com- economy could serve as a model to the More food will have to be imported. ments on the world economy. At the world. See Agriculture/The Economy, page 9 moment, Cuba is reeling from the impact See The Economy, Pages 6 & 7 of natural and man-made disasters that Aid Package in Jeopardy raise questions about whether Cuba’s Condos in Cuba Despite the dire situation, President economy will experience any growth A Canadian company is joining Gran Castro grandly rebuffed U.S. participation in whatsoever this year. But that has not Caribe to build Cuba’s first condos and time- an emergency food relief plan that the UN is stopped him from pointing with glee at share facilities. The development will be trying to put together. This has put the the plunge in stock market prices. located on some prime beachfront property. entire package in jeopardy. -

Culture Box of Cuba

CUBA CONTENIDO CONTENTS Acknowledgments .......................3 Introduction .................................6 Items .............................................8 More Information ........................89 Contents Checklist ......................108 Evaluation.....................................110 AGRADECIMIENTOS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Contributors The Culture Box program was created by the University of New Mexico’s Latin American and Iberian Institute (LAII), with support provided by the LAII’s Title VI National Resource Center grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Contributing authors include Latin Americanist graduate students Adam Flores, Charla Henley, Jennie Grebb, Sarah Leister, Neoshia Roemer, Jacob Sandler, Kalyn Finnell, Lorraine Archibald, Amanda Hooker, Teresa Drenten, Marty Smith, María José Ramos, and Kathryn Peters. LAII project assistant Katrina Dillon created all curriculum materials. Project management, document design, and editorial support were provided by LAII staff person Keira Philipp-Schnurer. Amanda Wolfe, Marie McGhee, and Scott Sandlin generously collected and donated materials to the Culture Box of Cuba. Sponsors All program materials are readily available to educators in New Mexico courtesy of a partnership between the LAII, Instituto Cervantes of Albuquerque, National Hispanic Cultural Center, and Spanish Resource Center of Albuquerque - who, together, oversee the lending process. To learn more about the sponsor organizations, see their respective websites: • Latin American & Iberian Institute at the -

The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Legacies

1 The Revolutions of 1989 and Their Legacies Vladimir Tismaneanu The revolutions of 1989 were, no matter how one judges their nature, a true world-historical event, in the Hegelian sense: they established a historical cleavage (only to some extent conventional) between the world before and after 89. During that year, what appeared to be an immutable, ostensibly indestructible system collapsed with breath-taking alacrity. And this happened not because of external blows (although external pressure did matter), as in the case of Nazi Germany, but as a consequence of the development of insuperable inner tensions. The Leninist systems were terminally sick, and the disease affected first and foremost their capacity for self-regeneration. After decades of toying with the ideas of intrasystemic reforms (“institutional amphibiousness”, as it were, to use X. L. Ding’s concept, as developed by Archie Brown in his writings on Gorbachev and Gorbachevism), it had become clear that communism did not have the resources for readjustment and that the solution lay not within but outside, and even against, the existing order.1 The importance of these revolutions cannot therefore be overestimated: they represent the triumph of civic dignity and political morality over ideological monism, bureaucratic cynicism and police dictatorship.2 Rooted in an individualistic concept of freedom, programmatically skeptical of all ideological blueprints for social engineering, these revolutions were, at least in their first stage, liberal and non-utopian.3 The fact that 1 See Archie Brown, Seven Years that Changed the World: Perestroika in Perspective (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), pp. 157-189. In this paper I elaborate upon and revisit the main ideas I put them forward in my introduction to Vladimir Tismaneanu, ed., The Revolutions of 1989 (London and New York: Routledge, 1999) as well as in my book Reinventing Politics: Eastern Europe from Stalin to Havel (New York: Free Press, 1992; revised and expanded paperback, with new afterword, Free Press, 1993). -

The Doctrine of Angels

Angelology: The Doctrine of Angels Related Media Introduction The fact that God has created a realm of personal beings other than mankind is a fitting topic for systematic theological studies for it naturally broadens our understanding of God, of what He is doing, and how He works in the universe. We are not to think that man is the highest form of created being. As the distance between man and the lower forms of life is filled with beings of various grades, so it is possible that between man and God there exist creatures of higher than human intelligence and power. Indeed, the existence of lesser deities in all heathen mythologies presumes the existence of a higher order of beings between God and man, superior to man and inferior to God. This possibility is turned into certainty by the express and explicit teaching of the Scriptures. It would be sad indeed if we should allow ourselves to be such victims of sense perception and so materialistic that we should refuse to believe in an order of spiritual beings simply because they were beyond our sight and touch.1 The study of angels or the doctrine of angelology is one of the ten major categories of theology developed in many systematic theological works. The tendency, however, has been to neglect it. As Ryrie writes, One has only to peruse the amount of space devoted to angelology in standard theologies to demonstrate this. This disregard for the doctrine may simply be neglect or it may indicate a tacit rejection of this area of biblical teaching. -

The Making of SYRIZA

Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line Panos Petrou The making of SYRIZA Published: June 11, 2012. http://socialistworker.org/print/2012/06/11/the-making-of-syriza Transcription, Editing and Markup: Sam Richards and Paul Saba Copyright: This work is in the Public Domain under the Creative Commons Common Deed. You can freely copy, distribute and display this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit the Encyclopedia of Anti-Revisionism On-Line as your source, include the url to this work, and note any of the transcribers, editors & proofreaders above. June 11, 2012 -- Socialist Worker (USA) -- Greece's Coalition of the Radical Left, SYRIZA, has a chance of winning parliamentary elections in Greece on June 17, which would give it an opportunity to form a government of the left that would reject the drastic austerity measures imposed on Greece as a condition of the European Union's bailout of the country's financial elite. SYRIZA rose from small-party status to a second-place finish in elections on May 6, 2012, finishing ahead of the PASOK party, which has ruled Greece for most of the past four decades, and close behind the main conservative party New Democracy. When none of the three top finishers were able to form a government with a majority in parliament, a date for a new election was set -- and SYRIZA has been neck-and-neck with New Democracy ever since. Where did SYRIZA, an alliance of numerous left-wing organisations and unaffiliated individuals, come from? Panos Petrou, a leading member of Internationalist Workers Left (DEA, by its initials in Greek), a revolutionary socialist organisation that co-founded SYRIZA in 2004, explains how the coalition rose to the prominence it has today. -

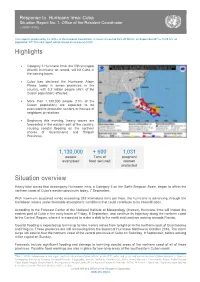

Highlights Situation Overview

Response to Hurricane Irma: Cuba Situation Report No. 1. Office of the Resident Coordinator ( 07/09/ 20176) This report is produced by the Office of the Resident Coordinator. It covers the period from 20:00 hrs. on September 06th to 14:00 hrs. on September 07th.The next report will be issued on or around 08/09. Highlights Category 5 Hurricane Irma, the fifth strongest Atlantic hurricane on record, will hit Cuba in the coming hours. Cuba has declared the Hurricane Alarm Phase today in seven provinces in the country, with 5.2 million people (46% of the Cuban population) affected. More than 1,130,000 people (10% of the Cuban population) are expected to be evacuated to protection centers or houses of neighbors or relatives. Beginning this evening, heavy waves are forecasted in the eastern part of the country, causing coastal flooding on the northern shores of Guantánamo and Holguín Provinces. 1,130,000 + 600 1,031 people Tons of pregnant evacuated food secured women protected Situation overview Heavy tidal waves that accompany Hurricane Irma, a Category 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Scale, began to affect the northern coast of Cuba’s eastern provinces today, 7 September. With maximum sustained winds exceeding 252 kilometers (km) per hour, the hurricane is advancing through the Caribbean waters under favorable atmospheric conditions that could contribute to its intensification. According to the Forecast Center of the National Institute of Meteorology (Insmet), Hurricane Irma will impact the eastern part of Cuba in the early hours of Friday, 8 September, and continue its trajectory along the northern coast to the Central Region, where it is expected to make a shift to the north and continue moving towards Florida. -

The European Suffrage Movement and Democracy in the European Community, 1948-1973

Journal of Contemporary European Research Volume 10, Issue 1 (2014) A Salutary Shock: The European Suffrage Movement and Democracy in the European Community, 1948-1973 Eric O’Connor University of Wisconsin-Madison Citation O’Connor, E. (2014). ‘A Salutary Shock: The European Suffrage Movement and Democracy in the European Community, 1948-1973’, Journal of Contemporary European Research. 10 (1), pp. 57-73. First published at: www.jcer.net Volume 10, Issue 1 (2014) jcer.net Eric O’Connor Abstract This article examines the experience of democratic participation during the European Community’s most undemocratic era, 1948-1973. An important segment of European activists, a suffrage movement of sorts, considered European-wide elections as the most effective technique of communicating European unity and establishing the EC’s democratic credentials. Going beyond strictly information dissemination, direct elections would engage citizens in ways pamphlets, protests, and petitions could not. Other political elites, however, preferred popular democracy in the form of national referendums, if at all. This article examines the origins and implications of incorporating the two democratic procedures (national referendums and direct elections) into the EC by the end of the 1970s. It also identifies a perceived deficit in democracy as a spectre that has haunted European activists since the first post-war European institutions of the late 1940s, a spectre that has always been closely related to an information deficit. Based on archival research across Western