The Citrus Replanting Scheme on Atiu, Cook Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Āirani Cook Islands Māori Language Week

Te ’Epetoma o te reo Māori Kūki ’Āirani Cook Islands Māori Language Week Education Resource 2016 1 ’Akapapa’anga Manako | Contents Te 'Epetoma o te reo Māori Kūki 'Āirani – Cook Islands Māori Language Week Theme 2016……………………………………………………….. 3 Te tangianga o te reo – Pronunciation tips …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Tuatua tauturu – Encouraging words …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 7 Tuatua purapura – Everyday phrases……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 9 ’Anga’anga raverave no te ’Epetoma o te reo Māori Kūki ’Āirani 2016 - Activity ideas for the Cook Islands Language Week 2016… 11 Tua e te au ’īmene – Stories and songs………………………………………………………………………………………..………………………………………………… 22 Te au toa o te reo Māori Kūki ’Āirani – Cook Islands Māori Language Champions………………………………………………………………………….. 27 Acknowledgements: Teremoana MaUa-Hodges We wish to acknowledge and warmly thank Teremoana for her advice, support and knowledge in the development of this education resource. Te ’Epetoma o te reo Teremoana is a language and culture educator who lives in Māori Kūki ’Āirani Kūmiti Wellington Porirua City, Wellington. She hails from te vaka Takitumu ō Rarotonga, ‘Ukarau e ‘Ingatu o Atiu Enuamanu, and Ngāpuhi o Aotearoa. 2 Te 'Epetoma o te reo Māori Kūki 'Āirani - Cook Islands Māori Language Week 2016 Kia āriki au i tōku tupuranga, ka ora uatu rai tōku reo To embrace my heritage, my language lives on Our theme for Cook Islands Māori Language Week in 2016 is influenced by discussions led by the Cook Islands Development Agency New Zealand (CIDANZ) with a group of Cook Islands māpū (young people). The māpū offered these key messages and helpful interpretations of te au tumu tāpura (the theme): NGUTU’ARE TANGATA │ FAMILY Embrace and celebrate ngutu’are tangata (family) and tapere (community) connections. -

Cook Islands of the Basicbasic Informationinformation Onon Thethe Marinemarine Resourcesresources Ofof Thethe Cookcook Islandsislands

Basic Information on the Marine Resources of the Cook Islands Basic Information on the Marine Resources of the Cook Islands Produced by the Ministry of Marine Resources Government of the Cook Islands and the Information Section Marine Resources Division Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) with financial assistance from France . Acknowledgements The Ministry of Marine Resources wishes to acknowledge the following people and organisations for their contribution to the production of this Basic Information on the Marine Resources of the Cook Islands handbook: Ms Maria Clippingdale, Australian Volunteer Abroad, for compiling the information; the Cook Islands Natural Heritage Project for allowing some of its data to be used; Dr Mike King for allowing some of his drawings and illustration to be used in this handbook; Aymeric Desurmont, Secretariat of the Pacific Community (SPC) Fisheries Information Specialist, for formatting and layout and for the overall co-ordination of efforts; Kim des Rochers, SPC English Editor for editing; Jipé Le-Bars, SPC Graphic Artist, for his drawings of fish and fishing methods; Ministry of Marine Resources staff Ian Bertram, Nooroa Roi, Ben Ponia, Kori Raumea, and Joshua Mitchell for reviewing sections of this document; and, most importantly, the Government of France for its financial support. iii iv Table of Contents Introduction .................................................... 1 Tavere or taverevere ku on canoes ................................. 19 Geography ............................................................................ -

Oral History and Traces of the Past in a Polynesian Landscape1

Anna-Leena Siikala SPATIAL MEMORY AND NARRATION: ORAL HISTORY AND TRACES OF THE PAST IN A POLYNESIAN LANDSCAPE1 hen Inepo, a 27-year-old fisherman obvious than that they set them primarily in on Mauke wanted to tell the legend of space, only secondarily in time.’ (Glassie 1982: WAkaina, a character important in the history of 662–663). the island, he said: ‘Let’s go to the place where Inepo can be compared to the young Akaina’s body was dried. It is on our land, near Irish men to whom the historical narratives the orange grove.’ The day was hot and we are meaningful accounts of places. in fact, the hesitated, why not just tell the story right here oral historic narratives of most commoners on in the village green. Inepo, however, insisted on Mauke resemble the historical folklore of an showing us the place and told the legend which Irish or another European village in their lack of ended: ‘This place, I know it, I still remember it a precise time perspective. from my childhood (…) they (Akaina and his Inepo’s teacher in the art of historical party) used to stay in Tane’s marae (cult place). narratives, called tua taito ‘old speech’, does, That is also on our land.’2 however, represent a different kind of oral Inepo’s vivid narrative did not focus on historian. He was Papa Aiturau, a tumu korero, the time perspective or historical context. ‘a source of history’, who initiated children Dramatic events were brought from the past to into the past of their own kin group. -

I Uta I Tai — a Preliminary Account of Ra'ui on Mangaia, Cook Islands

4 I uta i tai — a preliminary account of ra’ui on Mangaia, Cook Islands Rod Dixon Background Mangaia is the most southerly of the Cook Islands with a land area of 52 square kilometres. It comprises the highly weathered remains of a volcanic cone that emerged from the Pacific some 20 million years ago and stands 15,600 feet (4,750 metres) above the ocean floor. In the late Pleistocene epoch, tectonic activity resulted in the elevation of the island and reef. Subsequent undercutting of the elevated reef by run off from the former volcanic core has helped create the current formation of the limestone makatea which surrounds the island, standing up to 200 feet (60 metres) above sea level. As indicated in Figure 8, the island has a radial drainage system. From its central hill, Rangimoti’a, sediment is carried by rainwater down valley systems as far as the makatea wall, thus creating the current alluvial valleys and swamps. 79 THE RAHUI Figure 8: Mangaia Island, indicating puna divisions and taro swamps Source: Rod Dixon Kirch provides archaeological evidence that this erosion and deposition was accelerated by forest clearance and shifting cultivation of the inland hills somewhere between 1,000 and 500 years ago.1 1 Kirch, P.V., 1997. ‘Changing landscapes and sociopolitical evolution in Mangaia, Central Polynesia’. In P.V. Kirch & T.L. Hunt (eds), Historical Ecology in the Pacific Islands. New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 163. 80 4. I UTA I TAI — A PRELIMINARY ACCOUNT OF RA’UI ON MANGAIA, COOK ISLANDS Political and economic zones Mangaians divide the island into radial territories, pie-shaped slices based around each of the six main river valleys and swamps. -

Scanned Using Fujitsu 6670 Scanner and Scandall Pro Ver 1.7 Software

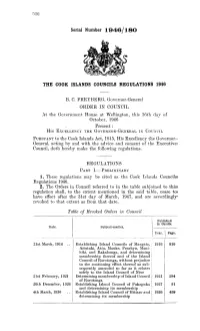

516 Serial Number 1946/ 180 THE COOK ISLANDS COUNCILS REGULATIONS 1946 B. C. FREYBERG, Governor-General ORDER IN COUNCIL _H the Government House at Wellington, this 16th day of October, 1946 Present: HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL IN COUNCIL PURSUANT to the Cook Islands Act, 1915, His Excellency the Governor General, acting by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, doth hereby make the following regulations. REGULATIONS PART L-PRELDIINARY 1. These regulations may be cited as the Cook Islands Councils Regulations 1946. 2. The Orders in Council referred to in the table subjoined to this regulation shall, to the extent mentioned in the said table, cease to have effect after the 31st day of March, 1947, and are accordingly revoked to that extent as from that date. Table of Revoked Orders in Council Published in Gazette. Date. Subject·matter. Year. \ Page. 21st March, 1916 Establishing Island Councils of Mangaia, 19161 910 Aitutaki, Atiu, Mauke, Penrhyn, Mani· . hiki, and Rakahanga, and determining : membership thereof and of the Island Council of Rarotonga, without prejudice to the continuing effect thereof as sub sequently amended so far as it relates solely to the Island Council of Niue 21st February, 1921 Determining membership of Island Council 1921 594 of Rarotonga 20th December, 1926 Establishing Island Council of Pukapuka 1927 51 and determining its membership 4th March, 1936 Establishing Island Council of Mitiaro and 1936 45Q determining its membership I 1946/180] Cook Islands Councils Regulations 1946 517 3. The respective Island Councils established by the enactments hereby revoked and subsisting at the time of coming into force of these regulations shall be deemed to, be the respective Island Councils esta blished by these regulations. -

ELECTORAL ACT 2004 ANALYSIS 1. Short Title 2. Interpretation PART 1

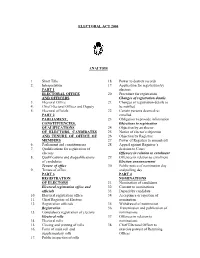

ELECTORAL ACT 2004 ANALYSIS 1. Short Title 18. Power to destroy records 2. Interpretation 19. Application for registration by PART 1 electors ELECTORAL OFFICE 20. Procedure for registration AND OFFICERS Changes of registration details 3. Electoral Office 21. Changes of registration details to 4. Chief Electoral Officer and Deputy be notified 5. Electoral officials 22. Certain persons deemed re- PART 2 enrolled PARLIAMENT, 23. Obligation to provide information CONSTITUENCIES, Objections to registration QUALIFICATIONS 24. Objection by an elector OF ELECTORS, CANDIDATES 25. Notice of elector’s objection AND TENURE OF OFFICE OF 26. Objection by Registrar MEMBERS 27. Power of Registrar to amend roll 6. Parliament and constituencies 28. Appeal against Registrar’s 7. Qualifications for registration of decision to Court electors Offences in relation to enrolment 8. Qualifications and disqualifications 29. Offences in relation to enrolment of candidates Election announcement Tenure of office 30. Public notice of nomination day 9. Tenure of office and polling day PART 3 PART 4 REGISTRATION NOMINATIONS OF ELECTORS 31. Nomination of candidates Electoral registration office and 32. Consent to nominations officials 33. Deposit by candidate 10. Electoral registration office 34. Acceptance or rejection of 11. Chief Registrar of Electors nomination 12. Registration officials 35. Withdrawal of nomination Registration 36. Transmission and publication of 13. Compulsory registration of electors nominations Electoral rolls 37. Offences in relation to 14. Electoral rolls nominations 15. Closing and printing of rolls 38. Chief Electoral Officer to 16. Form of main roll and exercise powers of Returning supplementary rolls Officer 17. Public inspection of rolls 2 Electoral Uncontested elections PART 6 39. -

Auē`Anga Ngākau

Auē`anga Ngākau - Silent Tears The Impact of Colonisation on Traditional Adoption Lore in the Cook Islands: Examining the Status of Tamariki `Āngai and their Entitlements. Diane Charlie-Puna A thesis submitted to Auckland University of Technology In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Philosophy (MPhil) 2018 Te Ipukarea, The National Māori Language Institute Faculty of Culture and Society i Table of contents Table of contents ii Attestation of authorship vii Acknowledgements viii Dedication x Abstract xi Preface xii Orthographic Conventions xii Tamariki rētita vs Tamariki `āngai xii About the Researcher xiii Personal motivation for this thesis xiv Western and Indigenous xv Chapter Titles xv Chapter 1: Setting the Scene xvi Chapter 2: Literature Review xvi Chapter 3: Evolution of Adoption Practices xvi Chapter 4: Emotional Journey xvii Chapter 5: Law verses Lore xvii Chapter 6: New Beginnings and Recommendations xviii 1. CHAPTER ONE: SETTING THE SCENE - TE KAPUA`ANGA 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Methodology 2 1.2(a) Qualitative Descriptive Methodology 2 1.2(b) Social Identity Theory 3 1.2(c) Social Identification 5 1.2(d ) Social comparison 5 1.2(e) Psychoanalytic Theory 6 1.2(f) Ethological Theory 6 1.2(g) Social Role Theory 6 1.3 Method and Procedures for Undertaking Research 7 1.3(a) Insider-Research Approach 7 1.3(b) Participants 8 1.3(c) Traditional Leaders 8 ii 1.4 Tamariki `Āngai/Tamariki Rētita Participants 10 1.4(a) Recruitment of participants 12 1.4(b) Interview Process 13 1.4(c) Questions and Answers 13 1.5 Data Analysis 14 1.5(a) Author’s bias 14 1.5(b) Ethical Considerations 14 1.6 Indigenous Methodology 14 1.7 Metaphoric Ideology 16 Kete Ora`anga Model 17 Stage 1: Selection and Preparation 18 Stage 2: Weaving of the basket 20 Stage 3: Joining and Shaping of the basket 22 Stage 4: Closing of the bottom of the basket 23 The Final Product 25 1.8 Conclusion 25 2. -

Cook Islands Elections 2014 in Brief

Cook Islands Elections 2014 In Brief Contents Message from the Chief Electoral Officer ........................................................................ 3 Introduction ...................................................................................................................... 4 Electoral Process and Administration............................................................................... 4 Candidates and Political Parties ....................................................................................... 5 Registration and the Electoral Roll ................................................................................... 6 Election Methods .............................................................................................................. 8 Postal Voting ................................................................................................................ 8 Advance Voting ............................................................................................................ 8 Special Voting (Declaration) ........................................................................................ 8 Special Care .................................................................................................................. 8 Ordinary Voting ............................................................................................................ 8 Election Result .................................................................................................................. 9 Technological -

Avatiu Port Development Project

Involuntary Resettlement and Environment Safeguard Closure Report July, 2013 COO: L 2472/2473/2739 & G 0249 - Avatiu Port Development Project Prepared by Cook Islands Port Authority for the Government of the Cook Islands and the Asian Development Bank This involuntary resettlement and environment safeguard closure report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. PORTS AUTHORITY PO Box 84, Rarotonga, Cook Islands Phone (682) 21 921 Facsimile (682) 21 191 Avatiu Port Development Project (Loan 2472/2473/2739 - COO & Grant 0249 - COO) Involuntary Resettlement and Environment Closure Report July 2013 PORTS AUTHORITY PO Box 84, Rarotonga, Cook Islands Phone (682) 21 921 Facsimile (682) 21 191 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Numbers EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................... A. INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………........ B. PROJECT DESCRIPTION................................................................................... ..... C. ENVIRONMENT SAFEGUARD REQUIREMENTS…………………………………........ D. INVOLUNTARY RESETTLEMENT REQUIREMENTS................................................................ -

The Constitution of the Cook Islands

Constitution 1 COOK ISLANDS CONSTITUTION [WITH AMENDMENTS INCORPORATED] REPRINTED AS ON 21st December, 2004 INDEX PAGE The Constitution Cook Islands Constitution Act 1964 (N.Z.) Cook Islands Constitution Amendment Act 1965 (N.Z.) Cook Islands Constitution Act Commencement Order 1965 (S.R. 1965/128) Constitution Amendment Act 1968-69 (Repealed by s.23(1)(a), Constitution Amendment (No.9) Act 1980-81 (C.I.)) Constitution Amendment (No.2) Act 1968-69 Constitution Amendment (No.3) Act 1969 (Repealed by s.23(1)(c), Constitution Amendment (No.9) Act 1980-81 (C.I.)) Constitution Amendment (No.4) Act 1970 (Repealed by s.23(1)(d), Constitution Amendment (No.9) Act 1980-81 (C.I.)) Constitution Amendment (No.5) Act 1970 Constitution Amendment (No.6) Act 1973 Constitution Amendment (No.7) Act 1975 Constitution Amendment (No.8) Act 1978-79 (Repealed by s.23(1)(f), Constitution Amendment (No.9) Act 1980-81 (C.I.)) Constitution Amendment (No.9) Act 1980-81 Constitution Amendment (No.10) Act 1981-82 Constitution Amendment (No.11) Act 1982 Constitution Amendment (No.12) Act 1986 Constitution Amendment (No.13) Act 1991 Constitution Amendment (No.14) Act 1991 Constitution Amendment (No.15) Act 1993 Constitution Amendment (No.16) Act 1993-94 Constitution Amendment (No. 17) Act 1994-95 Constitution Amendment (No. 18) Act 1995-96 Constitution Amendment (No.19) Act 1995-96 Constitution Amendment (No.20) Act 1997 Constitution Amendment (No.21) Act 1997 Constitution Amendment (No.22) Act 1997 Constitution Amendment (No.23) Act 1999 Constitution Amendment (No. 24) Act 2001 Constitution Amendment (No. 25) Act 2002 Constitution Amendment (No. -

Aristocratic Titles and Cook Islands Nationalism Since Self-Government

Royal Backbone and Body Politic: Aristocratic Titles and Cook Islands Nationalism since Self-Government Jeffrey Sissons Nation building has everywhere entailed the encompassment of earlier or alternative imagined communities (Anderson 1991). European and Asian nationalists have incorporated monarchical and dynastic imagin ings into their modern communal designs; Islamic nationalists have derived principles oflegitimacy from an ideal ofreligious community; and African and Pacific leaders have used kinship ideologies to naturalize and lend an air of primordial authenticity to their postcolonial identities. Since self-government was gained in the Cook Islands in 1965, holders of tradi tional titles-ariki, mata'iapo, and rangatira-have come to symbolize continuity between a precolonial past and a postcolonial present. Albert Henry and Cook Islands leaders who followed him sought to include ele ments of this traditional hierarchy in the nation-state and, through ideo logical inversion, to represent themselves as ideally subordinate to, or in partnership with, its leadership. But including elements ofthe old in the new, the traditional in the mod ern, also introduces contradiction into the heart ofthe national imagining. Elements that at first expressed continuity between past and present may later come to serve as a perpetual reminder of rupture, of a past (a para dise?) that has been lost but might yet be regained. Since the late 1980s, in the context of a rapidly expanding tourist industry that values (as it commodifies) indigenous distinctiveness, Cook Islands traditional leaders have been pursuing, with renewed enthusiasm, a greater role in local gov ernment and more autonomy in deciding matters of land and title succes sion. -

New Zealand G.Azette

.l)umf.1. 112. 311 THE NEW ZEALAND G.AZETTE WELLINGTON, THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 24, 1938. Land taken for Housing Purposes in the Borough of N garuawahia. [L.S.] GALWAY, Governor-General. A PROCLAMATION. N pursuance and exercise of the powers and authorities vested in me by the Public Works Act, 1928, and section thirty-two I of the Statutes Amendm"ent Act, 1936, and of every other power and authority in anywise enabling me in this behalf, I, George Vere Arundell, Viscount Galway, Governor-General of the Dominion of New Zealand, do hereby proclaim and' declare that the land described in the Schedule hereto is hereby taken for housing purposes ; and I do also declare that this Proclamation shall take effect on and after the twenty-eighth day .of February, one thousand nine hundred and thirty-eight. SCHEDULE. Approximate I Areas of the Pieces Being Portion of Situated In I Situated In I Shown on Elan of Land taken. Blor,k I Survey District of I~~~ --------~ A. R, P. 0 3 4 Allotments 6, 7, and 8, Town of Newcastle VII Newcastle P.W.D. 980.67 · Yll11tiw. 3 2 8 Allotments 288, 289, 290, 291, 292, 293, 294, 309, VII 310, 311, 312, and 313, Town of Newcastle (S.O. 29350.) 0 2 0 Lots 1 and 2, D.P. 9832, a,nd being part Allotment VII P.W.D. 98404 169.A, Suburbs of Newcastle South (S.O. 29430.) (Auckland R.D.) (Borough of Ngaruawahia.) In the Auckland Land District ; as the same are more particularly delineated on the plan marked and coloured as above mentioned, and deposited in the office of the Minister of Public Works at Wellington, and thereon coloured as above mentioned.