The Asia Papers, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

Simple Or Complex? Learning to Predict Readability of Bengali Texts

Simple or Complex? Learning to Predict Readability of Bengali Texts Susmoy Chakraborty1*, Mir Tafseer Nayeem1*, Wasi Uddin Ahmad2 1Ahsanullah University of Science and Technology, 2University of California, Los Angeles [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Scores Readers Grade Levels 90 - 100 5th Grade Determining the readability of a text is the first step to its sim- plification. In this paper, we present a readability analysis tool 80 - 90 6th Grade capable of analyzing text written in the Bengali language to provide in-depth information on its readability and complexity. Despite being the 7th most spoken language in the world with 70 - 80 7th Grade 230 million native speakers, Bengali suffers from a lack of Readability th th fundamental resources for natural language processing. Read- Formulas 60 - 70 8 to 9 Grade ability related research of the Bengali language so far can be considered to be narrow and sometimes faulty due to the lack Input Document 50 - 60 10th to 12th Grade of resources. Therefore, we correctly adopt document-level readability formulas traditionally used for U.S. based educa- 30 - 50 College tion system to the Bengali language with a proper age-to-age comparison. Due to the unavailability of large-scale human- annotated corpora, we further divide the document-level task 0 - 30 College Graduate into sentence-level and experiment with neural architectures, which will serve as a baseline for the future works of Ben- gali readability prediction. During the process, we present Figure 1: Readability prediction task. several human-annotated corpora and dictionaries such as a document-level dataset comprising 618 documents with 12 different grade levels, a large-scale sentence-level dataset com- tools such as Grammarly2 and Readable.3 This measurement prising more than 96K sentences with simple and complex plays a significant role in many places, such as education, labels, a consonant conjunct count algorithm and a corpus of health care, and government (Grigonyte et al. -

Name : Mr. Rajarshi Chakrabarty Designation : Assistant Professor

Name : Mr. Rajarshi Chakrabarty Designation : Assistant Professor Email, Contact Number & Address : [email protected]/[email protected] Research Area/ Ph. D: Urban History Distinction, Awards & Scholarships: Awarded Professor B.B. Chaudhuri Prize for Best Paper in the section on Social & Economic History of India, presented at the 71st session of the Indian History Congress, 2011. Publication: International: 1. Raja Krisnanath:Bangla Renaissance Ekjon Ujjal kintu Abahelita Baktito, published in Itihas Probondha Mala 2010, Itihas Academy, Dhaka, ISSN 1995-1000. 2. Krishnath College er Troi: Masterda Suryasen, Abul Barkat o Anowar Pasha, published in Itihas Probondha Mala 2011, Itihas Academy, Dhaka, ISSN 1995-1000. 3. Desh Bibhager Prekshapote Murshidabad Jela, published in Itihas Samity Patrika, Bangladesh Itihas Samity, ISSN 1560-7585. National Level Publication: 1. Shatranj Ke Khiladi and Umrao Jaan: Revisiting History through Films (received Professor B. B. Chaudhuri Prize), published in the Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, 71st Session, Malda, 2010-11, ISSN 2249-1937. 2. Bharater Jouna Sankhaloghu Andolon er Opor Bishwayaner Probhab, published in Proceedings of the UGC Sponsored National Seminar on “One and a half decade of Globalization”, organized by Barrackpore Rashtraguru Surendranath College and Samaj Bijwan Paricharcha-O-Gabesona Samsad. 3. Emulating Radha for Krsna Bhakti, published in the proceedings of UGC Sponsored National Seminar held at Krishnagar Govt. College titled Panchadas abong Sorosh Sataker Bhakti o Sufi Andolon: tar Aitihasik, Rajnaitik, abong Darshonik Prekshapot Bichar. State Level Publication: 1. Poschimbanga jounata o samajik linga nirman er korana prantik manus der sangathita andolon, published in Itihas Anusandhan 23, Paschimbanga Itihas Samsad. Local Level Publication: 1. -

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2012-2013 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT (%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 67059 0.002525667 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 579134 0.021812132 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1172263 0.044151362 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 373181 0.01405525 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 390958 0.014724791 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 172950 0.006513878 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 366211 0.013792736 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 398436 0.015006438 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 180263 0.00678931 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 265972 0.010017399 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 4172 0.000157132 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 297035 0.011187336 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410280 HELAPURI NEWS TELUGU DAILY(E) 67795 0.002553387 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 152550 0.005745545 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410405 VASISTA TIMES TELUGU DAILY(E) 62805 0.002365447 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 369397 0.013912732 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 239960 0.0090377 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 209853 -

State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance Among the Santal in Bangladesh

The Issue of Identity: State Denial, Local Controversies and Everyday Resistance among the Santal in Bangladesh PhD Dissertation to attain the title of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) Submitted to the Faculty of Philosophische Fakultät I: Sozialwissenschaften und historische Kulturwissenschaften Institut für Ethnologie und Philosophie Seminar für Ethnologie Martin-Luther-University Halle-Wittenberg This thesis presented and defended in public on 21 January 2020 at 13.00 hours By Farhat Jahan February 2020 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Reviewers: Prof. Dr. Burkhard Schnepel Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Assessment Committee: Prof. Dr. Carmen Brandt Prof. Dr. Kirsten Endres Prof. Dr. Rahul Peter Das To my parents Noor Afshan Khatoon and Ghulam Hossain Siddiqui Who transitioned from this earth but taught me to find treasure in the trivial matters of life. Abstract The aim of this thesis is to trace transformations among the Santal of Bangladesh. To scrutinize these transformations, the hegemonic power exercised over the Santal and their struggle to construct a Santal identity are comprehensively examined in this thesis. The research locations were multi-sited and employed qualitative methodology based on fifteen months of ethnographic research in 2014 and 2015 among the Santal, one of the indigenous groups living in the plains of north-west Bangladesh. To speculate over the transitions among the Santal, this thesis investigates the impact of external forces upon them, which includes the epochal events of colonization and decolonization, and profound correlated effects from evangelization or proselytization. The later emergence of the nationalist state of Bangladesh contained a legacy of hegemony allowing the Santal to continue to be dominated. -

2 Apar Gupta New Style Complete.P65

INDIAN LAWYERS IN POPULAR HINDI CINEMA 1 TAREEK PAR TAREEK: INDIAN LAWYERS IN POPULAR HINDI CINEMA APAR GUPTA* Few would quarrel with the influence and significance of popular culture on society. However culture is vaporous, hard to capture, harder to gauge. Besides pure democracy, the arts remain one of the most effective and accepted forms of societal indicia. A song, dance or a painting may provide tremendous information on the cultural mores and practices of a society. Hence, in an agrarian community, a song may be a mundane hymn recital, the celebration of a harvest or the mourning of lost lives in a drought. Similarly placed as songs and dance, popular movies serve functions beyond mere satisfaction. A movie can reaffirm old truths and crystallize new beliefs. Hence we do not find it awkward when a movie depicts a crooked politician accepting a bribe or a television anchor disdainfully chasing TRP’s. This happens because we already hold politicians in disrepute, and have recently witnessed sensationalistic news stories which belong in a Terry Prachet book rather than on prime time news. With its power and influence Hindi cinema has often dramatized courtrooms, judges and lawyers. This article argues that these dramatic representations define to some extent an Indian lawyer’s perception in society. To identify the characteristics and the cornerstones of the archetype this article examines popular Bollywood movies which have lawyers as its lead protagonists. The article also seeks solutions to the lowering public confidence in the legal profession keeping in mind the problem of free speech and censorship. -

Peculiarities of Indian English As a Separate Language

Propósitos y Representaciones Jan. 2021, Vol. 9, SPE(1), e913 ISSN 2307-7999 Special Number: Educational practices and teacher training e-ISSN 2310-4635 http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE1.913 RESEARCH ARTICLES Peculiarities of Indian English as a separate language Características del inglés indio como idioma independiente Elizaveta Georgievna Grishechko Candidate of philological sciences, Assistant Professor in the Department of Foreign Languages, Faculty of Economics, RUDN University, Moscow, Russia. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0799-1471 Gaurav Sharma Ph.D. student, Assistant Professor in the Department of Foreign Languages, Faculty of Economics, RUDN University, Moscow, Russia. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3627-7859 Kristina Yaroslavovna Zheleznova Ph.D. student, Assistant Professor in the Department of Foreign Languages, Faculty of Economics, RUDN University, Moscow, Russia. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8053-703X Received 02-12-20 Revised 04-25-20 Accepted 01-13-21 On line 01-21-21 *Correspondence Cite as: Email: [email protected] Grishechko, E., Sharma, G., Zheleznova, K. (2021). Peculiarities of Indian English as a separate language. Propósitos y Representaciones, 9 (SPE1), e913. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2021.v9nSPE1.913 © Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, 2021. This article is distributed under license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/) Peculiarities of Indian English as a separate language Summary The following paper will reveal the varieties of English pronunciation in India, its features and characteristics. This research helped us to consider the history of occurrence of English in India, the influence of local languages on it, the birth of its own unique English, which is used in India now. -

REFUGEECOSATT3.Pdf

+ + + Refugees and IDPs in South Asia Editor Dr. Nishchal N. Pandey + + Published by Consortium of South Asian Think Tanks (COSATT) www.cosatt.org Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) www.kas.de First Published, November 2016 All rights reserved Printed at: Modern Printing Press Kathmandu, Nepal. Tel: 4253195, 4246452 Email: [email protected] + + Preface Consortium of South Asian Think-tanks (COSATT) brings to you another publication on a critical theme of the contemporary world with special focus on South Asia. Both the issues of refugees and migration has hit the headlines the world-over this past year and it is likely that nation states in the foreseeable future will keep facing the impact of mass movement of people fleeing persecution or war across international borders. COSATT is a network of some of the prominent think-tanks of South Asia and each year we select topics that are of special significance for the countries of the region. In the previous years, we have delved in detail on themes such as terrorism, connectivity, deeper integration and the environment. In the year 2016, it was agreed by all COSATT member institutions that the issue of refugees and migration highlighting the interlinkages between individual and societal aspirations, reasons and background of the cause of migration and refugee generation and the role of state and non-state agencies involved would be studied and analyzed in depth. It hardly needs any elaboration that South Asia has been both the refugee generating and refugee hosting region for a long time. South Asian migrants have formed some of the most advanced and prosperous diasporas in the West. -

Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited Corporate Investment Wing Sustainable Finance Division Corporate Social Responsibility Department Head Office, Dhaka

Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited Corporate Investment Wing Sustainable Finance Division Corporate Social Responsibility Department Head Office, Dhaka. Sub: Result of IBBL Scholarship Program, HSC Level-2019 Following 1500(Male-754, Female-746) students mentioned below have been selected finally for IBBL Scholarship program, HSC Level -2019. Sl. No. Name of Branch Beneficiary ID Student's Name Father's Name Mother's Name 1 Agrabad Branch 8880202516103 Halimatus Sadia Didarul Alam Jesmin Akter 2 Agrabad Branch 8880202516305 Imam Hossain Mahbubul Hoque Aleya Begum 3 Agrabad Branch 8880202508003 Md Mahmudul Hasan Al Qafi Mohammad Mujibur Rahman Shaheda Akter 4 Agrabad Branch 8880202516204 Proma Mallik Gopal Mallik Archana Mallik 5 Alamdanga Branch 8880202313016 Mst. Husniara Rupa Md. Habibur Rahman Mst. Nilufa Yeasmin 6 Alamdanga Branch 8880202338307 Sharmin Jahan Shormi Md. Abdul Khaleque Israt Jahan 7 Alanga SME/Krishi Branch 8880202386310 Tammim Khan Mim Md. Gofur Khan Mst. Hamida Khanom 8 Amberkhana Branch 8880202314017 Fahmida Akter Nitu Babul Islam Najma Begum 9 Amberkhana Branch 8880202402015 Fatema Akter Abdul Kadir Peyara Begum 10 Amberkhana Branch 8880202252201 Mahbubur Rahman Md. Juned Ahmed Mst. Shomurta Begum 11 Amberkhana Branch 8880202208505 Md. Al-Amin Moin Uddin Rafia Begum 12 Amberkhana Branch 8880202457814 Md. Ismail Hossen Md. Rasedul Jaman Ismotara Begum 13 Amberkhana Branch 8880202413118 Mst. Shima Akter Tofazzul Islam Nazma Begum 14 Amberkhana Branch 8880202378513 Tania Akther Muffajal Hossen Kamrun Nahar 15 Amberkhana Branch 8880202300618 Tanim Islam Tanni Shahidul Islam Shibli Islam 16 Amberkhana Branch 8880202234504 Tanjir Hasan Abdul Malik Rahena Begum 17 Anderkilla Branch 8880202497414 Arpita Barua Alak Barua Tapasi Barua 18 Anderkilla Branch 8880202269108 Sakibur Rahman Mohammad Younus Ruby Akther 19 Anwara Branch 8880202320115 Jinat Arabi Mohammad Fajlul Azim Raihan Akter 20 Anwara Branch 8880202263607 Mizanur Rahman Abdul Khalaque Monwara Begum 21 Anwara Branch 8880202181101 Mohammad Arif Uddin Mohammad Shofi Fatema Begum Sl. -

Harrisons Malayalam Limited

Harrisons Malayalam Limited Instruments Amounts Rating Action (Rs. Crore1) (August 2016) Long-term - Fund based facilities 37.00 [ICRA]BB+(Stable) / withdrawn Long-term - Proposed facilities 6.10 Short-term - Non-fund based facilities 4.26 [ICRA]A4+ / withdrawn Long-term - Term loans 65.64 [ICRA]BB+(Stable) / outstanding ICRA has withdrawn the long-term rating of [ICRA]BB+ (pronounced ICRA double B plus)2 outstanding on the Rs. 37.00 crore fund based facilities, the Rs. 6.10 crore proposed facilities and the short-term rating of [ICRA]A4+ (pronounced ICRA A four plus) outstanding on the Rs. 4.26 crore non-fund based facilities of Harrisons Malayalam Limited (HML / the company), which was under notice of withdrawal, at the request of the company following the receipt of no dues letter from the bankers. The ratings for the aforementioned facilities are withdrawn as the period of notice of withdrawal ended. ICRA has long-term rating of [ICRA]BB+ (pronounced ICRA double B plus) with stable outlook outstanding for the Rs. 65.64 crore term loan facilities of the company. Company Profile HML is part of RPG Enterprises Ltd, an established group with interests in tyre, carbon black, power transmission, telecommunications, retail and entertainment. Incorporated in 1978, HML is primarily a rubber and tea producer, which contribute major share to the operating income. With eleven rubber plantations spread over 7,306 hectares of land in Kerala, HML is one of the major rubber plantation companies in India with a production of over 9,500 MT during FY2015. The Company is also one of the larger tea producers in South India, producing 15-18 million kgs of CTC and Orthodox teas in its thirteen tea gardens annually, the same spread over 6,021 hectares of land primarily in Kerala and some in Tamil Nadu. -

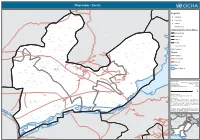

Overview - Swabi

Overview - Swabi Tor Ghar Legend Takhto Sar ! Shamma Khui ! Shama Shapla !^! ! National ! Khanpur ! ! Shahole !! Natian ! Khanpur Ajarh Province Post Gadai ! Natian ! Rizzar !!! District ! Mir Dandikot Sherdarra ! Shahe ! Sherdarah ! Settlements Mir Shahai Dandai ! Tor Gat ! Naranji Administartive Boundaries Mardan ! Badrai Chatara ! Buner ! Kund International Miralai ! Mehr Kamar Burai ! ! Bako ! Ali Dhand Bural ! Birgalai Mir Dai ! ! Pirgalai Khisha Khesha ! Naogram ! Provincial Kaniza Dheri ! ! Lakha Tibba Dheri Lakha Madda Khel Jabba ! Tiga Dheri Ghulama ! Mazghund ! Sikandarabad ! Muz Ghunar ! Jabba District Parmulai Bagga ! Jabba Purmali ! Ganikot ! ! Ganrikot Kodi Dherai Kodi Dheri ! Utla Bahai Baho Leran ! ! Satketar ! Palosai ! Gabai Amankot ! Salketai Ghabasanai ! Tehsil Bar Amrai Gabasanrai ! ! ! Gumbati Dheri Gumbat Dherai Amral Bala Bar Amral Bala ! Gunj Gago ! Dheri ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sangbalai ! Dherai ! Gani Chhatra Bar Dewalgari ! ! Line of control ! Punrawal Shewa ! Gangodher ! Aziz Dheri Banda ! Shingrai ! ! ! Katar Dheri ! Seri ! Kuz Amrai ! Achelai Rasoli Dheri Inian Dheri ! Gangu Dheri Shingrai Kuz Dewalgari ! ! Khalil ! ! ! Gangudhei Seri Injan Asota Sharif Asota Gangudher Makia ! ! Coastline Dheri Nuro Banda Chini Rafiqueabad ! Dheri ! Nakla Jogia ! Takhtaband Dheri Dagi ! Banda ! ! Spin ! Girro Sherghund Kani Aro Bore Badga ! Banda ! Katgram ! ! Sheikhjana ! Shaikh Jana Dakara Banda Roads ! Sukaili ! ! Ismaila Tali ! Adina ! ! ! Nawe Kili Pal Qadra ! Mangal Dheri Sandwa ! Chai ! Kalu Khan ! Shewa Chowk Aio Kolagar -

Final Report on Study for Modal Shift of Cargo Passing Through Siliguri

Study for modal shift of cargo passing through Siliguri Corridor destined for North-East and neighboring countries to IWT Final Report August, 2017 Submitted to Inland Waterways Authority of India (IWAI) April 2008 A Newsletter from Ernst & Young Study for modal shift of cargo passing through Siliguri Corridor destined for North-east and neighboring countries to IWT Contents Executive Summary .......................... 9 Introduction................................... 14 1. Appraisal of the Siliguri (Chicken’s Neck) Corridor 16 1.1 Geographical reach of the Corridor ....................................................................................... 16 2 Project Influence Area (PIA) ..... 18 2.1 PIA of Proposed Project ....................................................................................................... 18 2.1.1 Bongaigaon Cluster ...................................................................................................... 20 2.1.2 Guwahati Cluster.......................................................................................................... 20 2.1.3 Dibrugarh Cluster......................................................................................................... 21 2.1.4 Shillong Cluster ........................................................................................................... 22 2.1.5 Tripura Cluster ............................................................................................................ 22 2.1.6 Arunachal Pradesh Cluster ...........................................................................................