A Case Study of Kolkata's Newspapers' Coverage of Anti‑Indust

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2013-2014 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT(%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 209143 0.005310639 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 775695 0.019696744 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1618569 0.041099322 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 482558 0.012253297 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 534260 0.013566134 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 776771 0.019724066 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 201424 0.005114635 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 6550 0.00016632 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 1417145 0.035984687 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 546688 0.01388171 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 154046 0.003911595 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 18771 0.00047664 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 69244 0.00175827 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 153965 0.003909538 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 65899 0.001673333 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 172484 0.00437978 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 67128 0.00170454 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410114 STATE TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) -

Newspaper Wise.Xlsx

PRINT MEDIA COMMITMENT REPORT FOR DISPLAY ADVT. DURING 2012-2013 CODE NEWSPAPER NAME LANGUAGE PERIODICITY COMMITMENT (%)COMMITMENTCITY STATE 310672 ARTHIK LIPI BENGALI DAILY(M) 67059 0.002525667 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS ENGLISH DAILY(M) 579134 0.021812132 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1172263 0.044151362 PORT BLAIR ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 100820 DECCAN CHRONICLE ENGLISH DAILY(M) 373181 0.01405525 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI TELUGU DAILY(M) 390958 0.014724791 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 172950 0.006513878 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 366211 0.013792736 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410370 SAKSHI TELUGU DAILY(M) 398436 0.015006438 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 180263 0.00678931 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410400 TELUGU WAARAM TELUGU DAILY(M) 265972 0.010017399 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410495 VINIYOGA DHARSINI TELUGU MONTHLY 4172 0.000157132 ANANTHAPUR ANDHRA PRADESH 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY TELUGU DAILY(E) 297035 0.011187336 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410280 HELAPURI NEWS TELUGU DAILY(E) 67795 0.002553387 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410449 NETAJI TELUGU DAILY(E) 152550 0.005745545 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410405 VASISTA TIMES TELUGU DAILY(E) 62805 0.002365447 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410012 ELURU TIMES TELUGU DAILY(M) 369397 0.013912732 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410117 GOPI KRISHNA TELUGU DAILY(M) 239960 0.0090377 ELURU ANDHRA PRADESH 410009 RATNA GARBHA TELUGU DAILY(M) 209853 -

BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources: Secondary Sources

BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources: Records and Proceedings, Private and party organizational papers Autobiographies and Memoirs Personal Interviews with some important Political Leaders and Journalists of West Bengal Newspapers and Journals Other Documents Secondary Sources: Books (in English) Article (in English) Books (in Bengali) Article (in Bengali) Novels (in Bengali) 11 BIBLIOGRAPHY Primary Sources Records and Proceedings 1. Bengal Legislative Assembly Proceedings Vol. LII, No.4, 1938. 2. Bengal Legislative Assembly Proceedings, 1939, Vol. LIV, No.2, 3. Bengal Legislative Assembly Proceedings, 1940, vol. LVII, No.5. 4. Bengal Legislative Assembly Proceedings-Vol. LIII, No. 4. 5. Election Commission of India; Report on the First, Second, Third, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth General Election. 6. Fortnightly Report on the Political Situation in Bengal, 2nd half of April, 1947. Govt. of Bengal. 7. Home Department’s Confidential Political Records (West Bengal State Archives), (WBSA). 8. Police Records, Special Branch ‘PM’ and ‘PH’ Series, Calcutta (SB). 9. Public and Judicial Proceedings (L/P & I) (India Office Library and Records), (IOLR). 10. Summary of the Proceedings of the Congress Working Committee’, AICC-1, G-30/1945-46. 11. West Bengal Legislative Assembly Proceedings 1950-1972, 1974-1982. Private and party organizational papers 1. All India Congress committee Papers (Nehru Memorial Museum and Library), (NMML). 2. All Indian Hindu Mahasabha Papers (NMML) 3. Bengal Provislal Hindu Mahasabha Papers (NMML). 4. Kirn Sankar Roy Papers (Private collection of Sri Surjya Sankar Roy, Calcutta) 414 5. Ministry of Home Affairs Papers (National Achieves of India), (NAI). 6. Syama Prasad Mookerjee Papers (NMML). Autobiographies and Memoirs 1. Basu Hemanta Kumar, Bhasan O Rachana Sangrahra (A Collection of Speeches and Writings), Hemanta Kumar Basu Janma Satabarsha Utjapan Committee, Kolkata, 1994. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

LIST of MEDIA RIGHTS VIOLATIONS by JOURNALIST SAFETY INDICATES (JSIS), MAY 2018 to APRIL 2019 the Media Violations Are Categorised by the Journalist Safety Indicators

74 IFJ PRESS FREEDOM REPORT 2018–2019 LIST OF MEDIA RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY JOURNALIST SAFETY INDICATES (JSIS), MAY 2018 TO APRIL 2019 The media violations are categorised by the Journalist Safety Indicators. Other notable incidents are media violations recorded by the IFJ in its violation mapping. *Other notable incidents are media violations recorded by the IFJ. These are violations that fall outside the JSIs and are included in IFJ mapping on the South Asia Media Solidarity Network (SAMSN) Hub - samsn.ifj.org Afghanistan, was killed in an attack on the Sayeed Ali ina Zafari, political programs operator police chief of Kandahar, General Abdul Raziq. on Wolesi Jerga TV; and a Wolesi Jerga TV driver AFGHANISTAN The Taliban-claimed attack took place in the were entering the MOFA road for an interview in governor’s compound during a high-level official Zanbaq square when they were confronted by a JOURNALIST KILLINGS: 12 (Journalists: 5, meeting. Angar, along with others, was killed in policeman. Media staff: 7. Male: 12, Female: 0) the cross-fire. THREATS AGAINST THE LIVES OF June 5, 2018: Takhar JOURNALISTS: 8 December 4, 2018: Nangarhar Milli TV Takhar province reporter Merajuddin OTHER THREATS TO JOURNALISTS: Engineer Zalmay, director and owner or Enikass Sharifi was beaten up by the head of the None recorded radio and TV stations was kidnapped at 5pm community after a verbal disagreement. NON-FATAL ATTACKS ON JOURNALISTS: during a shopping trip. He was taken by armed 61 (Journalists: 52; Media staff: 9) men who arrived in an armoured vehicle. His June 11, 2018, Ghor THREATS AGAINST MEDIA INSTITUTIONS: 3 driver was shot and taken to hospital where he Saam Weekly Director, Nadeem Ghori, had his ATTACKS ON MEDIA INSTITUTIONS: 3 later died. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

Late Akshay Kumar Chaudhuri. Early Qualificat

CV Amiya K. Chaudhuri Dr. Amiya K. Chaudhuri Sr. Fellow (MAKAIAS) Father’s Name: Late Akshay Kumar Chaudhuri. Early Qualifications: BA (Hon) in Political Science and Economics (CU), MA in Political Science (CU), PH.D in Politics and Public Administration from the Department of Political Science, Calcutta University. Location: Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Institute of Asian Studies (MAKAIAS), 5, Ashraf Mistri Lane Kolkata-700019 Telephone: (033) 2454 6581, Fax (033) 2486 2049. Website: www.makaias.gov.in And Member of lokniti (CSDS, 29 Rajpur Road Delhi-54), website: www.lokniti.org] Residence: Golf Green, Phase – II, WIB (M) 19/4 & 19/5. Kolkata 700 095 Phone Numbers: 033-24737340, 09830005631 (M) Member: lokniti network (CSDS), 29, Rajpur Road, Delhi-54; website: www.lokniti.org E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 1 Positions held: Professor Chaudhuri taught Political Science in different Colleges (Calcutta University). He was a Post Graduate Guest Faculty in the Department of Political Science, Calcutta University, Department of Political Science with Rural Administration, Vidyasagar University, in NSOU Kolkata and Rabindra Bharati University in Distance Education System. Visited Soviet Russia and presented Two Papers in International Political Science Congress, and delivered a special lecture on “Indian Political Science today”, Paris, France, and Frankfurt, Germany. In short, more than 44 years of College and university teaching and equal number of years in Research Experience( both Normative and Empirical) till November 2011; many Seminar participations either as Paper giver or Chair. Amiya K. Chaudhuri till 2009 was Guest Faculty in the Department of Law, Calcutta University teaching Political Theory and Thought and, occasionally International Relations and in 2010 declined to accept next offer. -

Pan India Coverage on ReliAnce

COVERAGE REPORT on Reliance General Insurance introduces 5% extra discount on its Health Infinity product to encourage Covid vaccination Print Sr. Date Headline Publication Editions Pg. No no 1 May 19, Reliance General Insurance introduces 5% Dainik Bhaskar Jaipur 10 2021 extra discount on its Health Infinity product to Jodhpur 9 encourage Covid vaccination Kanpur 10 Lucknow 10 Noida 10 Ghaziabad 10 Varanasi 9 Allahabad 10 Meerut 10 Agra 10 Sultanpur 10 Gorakhpur 10 Bareilly 10 Aligarh 10 Faizabad 10 Jhansi 10 Mathura 9 Muzzaffar 10 Nagar 10 Muradabad 7 Saharanpur 7 Aurangabad 7 Nashik 7 Akola 7 Nagpur 7 Amravati 2 May 19, Reliance General Insurance introduces 5% Pioneer Kanpur 13 2021 extra discount on its Health Infinity product to Lucknow 10 encourage Covid vaccination Varanasi 10 Allahabad 10 Meerut 10 Agra 10 Sultanpur 10 Gorakhpur 10 Bareilly 10 Aligarh 10 Faizabad 10 Jhansi 10 Mathura 10 Muzzaffar 10 Nagar 9 Raipur 9 Muradabad 9 Saharanpur 10 3 May 22, Reliance General Insurance introduces 5% Navbharat Nagpur 5 2021 extra discount on its Health Infinity product to encourage Covid vaccination 4 May 19, Reliance General Insurance introduces 5% Yugmarg Chandigarh 9 2021 special discount on Health Infinity product Amritsar 9 Ludhiana 3 5 May 19, 5% discount for those who took vaccine Eenadu Hyderabad 16 2021 Vijayawada 16 Vizag 16 Bangalore 16 6 May 19, Reliance General Insurance to give Samachar Jagat Jaipur 6 2021 Jodhpur 2 7 May 19, Reliance General Insurance introduces 5% Mahasagar Nagpur 4 2021 extra discount on its Health Infinity -

Recognized Outlets for Svran Apeejay Journalism Foundation Grant

Recognized Outlets for Svran Apeejay Journalism Foundation Grant PRINT PUBLICATIONS Nai Duniya Nav Bharat Times (Hindi) Aajkal Nav Gujarat Samay Ahmedabad Mirror Navodaya Times (Hindi) Ajit Samachar(Hindi) Orissa Post Ajit(Punjabi) Pioneer (Hindi) Amar Ujala Punjab Kesari (Hindi), Editions: Punjab, Anand Bazar Patrika(Bengali) Haryana, Rajasthan, Himachal Pradesh, Bangalore Mirror Delhi, UP Bartaman (Bengali) Prabhat Khabar Business Standard Prajavani Daily Ajit(Urdu) Rajasthan Patrika Dainik Bhaskar Sakaal Times Dainik Divya Marathi(Marathi) Sanjevani Dainik Jagran Sangbad Pratidin Dainik Statesman (Bengali) Samyukta Karnataka Dainik Tribune (Hindi) The Sentinel DB Post (English) The Shillong Times Dinamalar The Hans India Dinamani The Asian Age Dinakaran The Deccan Chronicle Divya Bhaskar (Gujrat) The Deccan Herald DNA (English) The Financial Express Ebela (Bengali Tabloid) The Financial Chronicle Economic Times The Hindu Ei Samay The Hindu Business Line Ganashakti The Hindu (Tamil) Gujarat Samachar The New Indian Express Hind Samachar (Urdu) The Pioneer Hindustan Times The Statesman Hindustan (Hindi) The Telegraph Indian Express The Tribune Jag Bani (Punjabi) Times of India Jansatta Uttarbanga Sangbad Kesari Vijaya Karnataka (Kannadi) Lokmat (Marathi), Editions: Mumbai, The Assam Tribune Pune, Nagpur, Aurangabad, Nashik, Malyala Manorama Kolhapur, Sangli, Satara, Solapur, Akola, Ahmed Nagar, Jalgaon, Goa Loksatta (Marathi) MAGAZINES Maharashtra Times (Marathi) Mail Today (Tabloid) BBC Knowledge Mid-Day (Tabloid available in the Business -

Newspaper Wise Committment for All Advertisements in All State During the Period 2020-2021 As on 20/03/2021

NEWSPAPER WISE COMMITTMENT FOR ALL ADVERTISEMENTS IN ALL STATE DURING THE PERIOD 2020-2021 AS ON 20/03/2021. ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ------------------------ SL CODE NEWSPAPER PUBLICATION LAN/PER INSERTIONS SPACE(SQ.CM) AMOUNT(RS) NO STATE - ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 310672 ARTHIK LIPI PORT BLAIR BEN/D 9 3623.0000 37233.00 2 131669 INFO INDIA PORT BLAIR HIN/D 17 4256.0000 53565.00 3 132949 SANMARG PORT BLAIR HIN/D 31 11595.0000 173901.00 4 100771 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS PORT BLAIR ENG/D 44 9762.0000 132322.00 5 101067 THE ECHO OF INDIA PORT BLAIR ENG/D 110 28784.0000 399879.00 6 101692 THE PHOENIX POST PORT BLAIR ENG/D 1 408.0000 3183.00 7 101500 TODAY TIMES PORT BLAIR ENG/D 21 7650.0000 143669.00 8 101729 ARYAN AGE PORTBLAIR ENG/D 7 4483.0000 83832.00 9 132930 BANGLA MORCHA PORTBLAIR HIN/D 17 10320.0000 112788.00 STATE - ANDHRA PRADESH 10 410534 GRAMEENA JANA JEEVANA TEJAMGODAVARI AMALAPURAM TEL/D 1 408.0000 6143.00 11 410198 ANDHRA BHOOMI ANANTHAPUR TEL/D 2 480.0000 5342.00 12 410202 ANDHRA JYOTHI ANANTHAPUR TEL/D 11 2333.0000 67771.00 13 410345 ANDHRA PRABHA ANANTHAPUR TEL/D 14 7727.0000 116711.00 14 410632 ASHRAYA ANANTHAPUR TEL/D 1 408.0000 6143.00 15 410522 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM ANANTHAPUR TEL/D 4 2458.0000 62637.00 16 410370 SAKSHI ANANTHAPUR TEL/D 15 4570.0000 160811.00 17 410171 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA ANANTHAPUR TEL/D 4 2225.0000 58055.00 18 410398 ANDHRA DAIRY ELURU TEL/D 1 408.0000 7796.00 19 410117 GOPI KRISHNA ELURU TEL/D 1 825.0000 19034.00 20 410449 NETAJI ELURU TEL/D -

Microfinance Institutions Network

MICROFINANCE INSTITUTIONS NETWORK Media Coverage Report Microfinance Industry supports its Frontline Warriors during unprecedented times Region: Odisha/ Bihar/ Madhya Pradesh/ Maharashtra/ Karnataka/ West Bengal/ Assam/ Punjab Media Coverage Index S. No. Date Publication Name Edition ODISHA 1. 15.06.21 Samaya Odisha ( All Editions ) 2. 16.06.21 Odisha Bhaskar Odisha ( All Editions ) 3. 18.06.21 Agami Odisha Odisha ( All Editions ) 4. 19.06.21 Amruta Dunia Odisha ( All Editions ) 5. 18.06.21 Seithu Aramva Odisha ( All Editions ) 6. 19.06.21 Utkal Samaj Odisha ( All Editions ) 7. 18.06.21 Manthan Odisha ( All Editions ) 8. 15.06.21 Paryabekhyak Odisha ( All Editions ) 9. 15.06.21 Prasant Odisha ( All Editions ) 10. 15.06.21 Pramad Odisha ( All Editions ) 11. 17.06.21 Matrubhasa Odisha ( All Editions ) 12. 16.06.21 Agami Odisha Odisha ( All Editions ) 13. 18.06.21 Dunia Khabar Odisha ( All Editions ) 14. 15.06.21 Biswabani Odisha ( All Editions ) 15. 15.06.21 Dumani Mail Odisha ( All Editions ) 16. 16.06.21 Orissa Today Odisha ( All Editions ) 17. 17.06.21 Indian Era Odisha ( All Editions ) BIHAR 1. 19.06.21 Taasir Baksar/Bukaro 2. 18.06.21 Sahara Express Darbhanga 3. 18.06.21 Dainik Aaj Baksar 4. 18.06.21 Ek Sandesh Bukaro 5. 17.06.21 Satta Ki Khoj Darbhanga 6. 19.06.21 Sampurna Bharat Baksar 7. 18.06.21 Pratah Kiran Darbhanga 8. 17.06.21 Manush Khabar Bukaro 9. 17.06.21 Media Darshan Baksar 10. 18.06.21 Rashtriya Naveen Mail Bukaro MADHYA PRADESH 1. 19.06.21 Dainik Agradoot Shahdol 2. -

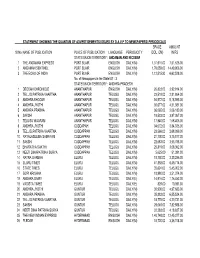

Statement Showing the Quantum of Advertisements

STATEMENT SHOWING THE QUANTUM OF ADVERTISEMENTS ISSUED BY D.A.V.P TO NEWSPAPERS/ PERIODICALS SPACE AMOUNT Sl No NAME OF PUBLICATION PLACE OF PUBLICATION LANGUAGE PERIODICITY (COL .CM) IN RS STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR 1 THE ANDAMAN EXPRESS PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,31,916.00 7,51,625.00 2 ANDAMAN SENTINEL PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,76,059.00 14,49,906.00 3 THE ECHO OF INDIA PORT BLAIR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 1,12,515.90 6,62,528.00 No. of Newspapers in the State/UT : 3 STATE/UNION TERRITORY : ANDHRA PRADESH 1 DECCAN CHRONICLE ANANTHAPUR ENGLISH DAILY(M) 26,823.00 3,92,914.00 2 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,519.00 2,81,864.00 3 ANDHRA BHOOMI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 54,572.00 5,18,595.00 4 ANDHRA JYOTHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 30,677.00 4,31,381.00 5 ANDHRA PRABHA ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 36,065.00 2,06,189.00 6 SAKSHI ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,533.00 3,87,367.00 7 TELUGU WAARAM ANANTHAPUR TELUGU DAILY(M) 17,940.00 1,68,405.00 8 ANDHRA JYOTHI CUDDAPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 34,072.00 3,84,335.00 9 TEL.J.D.PATRIKA VAARTHA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 23,566.00 2,68,399.00 10 RAYALASEEMA SAMAYAM CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 21,700.00 3,75,877.00 11 SAKSHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 22,683.00 3,95,788.00 12 BHARATHA SAKTHI CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 25,819.00 3,08,362.00 13 NEETI DINAPATRIKA SURYA CUDDAPPAH TELUGU DAILY(M) 5,625.00 51,391.00 14 RATNA GARBHA ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 18,750.00 3,33,285.00 15 ELURU TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 41,858.00 6,49,774.00 16 STATE TIMES ELURU TELUGU DAILY(M) 35,624.00