Heart of the Machine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

III. Discussion Questions A. Individual Stories Nathaniel Hawthorne

III. Discussion Questions a. Individual Stories Nathaniel Hawthorne, “Rappaccini’s Daughter” (1844) 1. As an early sf tale, this story makes important contributions to the sf megatext. What images, situations, plots, characters, settings, and themes do you recognize in Hawthorne’s story that recur in contemporary sf works in various media? 2. In Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, the worst sin is to violate, “in cold blood, the sanctity of the human heart.” In what ways do the male characters of “Rappaccini’s Daughter” commit this sin? 3. In what ways can Beatrice be seen as a pawn of the men, as a strong and intelligent woman, as an alien being? How do these different views interact with one another? 4. Many descriptions in the story lead us to question what is “Actual” and what is “Imaginary”? How do these descriptions function to work both symbolically and literally in the story? 5. What is the attitude toward science in the story? How can it be compared to the attitude toward science in other stories from the anthology? Jules Verne, excerpt from Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) 1. Who is narrator of this tale? In your opinion, why would Verne choose this particular character to be the narrator? Describe his relationship with the other members of this subterranean expedition. Many of Verne’s early novels feature a trio of protagonists who symbolize the “head,” the “heart,” and the “hand.” Why? How does this notion apply to the protagonists in Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth? 2. -

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Lightspeed Magazine, Issue 66 (November 2015)

TABLE OF CONTENTS Issue 66, November 2015 FROM THE EDITOR Editorial, November 2015 SCIENCE FICTION Here is My Thinking on a Situation That Affects Us All Rahul Kanakia The Pipes of Pan Brian Stableford Rock, Paper, Scissors, Love, Death Caroline M. Yoachim The Light Brigade Kameron Hurley FANTASY The Black Fairy’s Curse Karen Joy Fowler When We Were Giants Helena Bell Printable Toh EnJoe (translated by David Boyd) The Plausibility of Dragons Kenneth Schneyer NOVELLA The Least Trumps Elizabeth Hand NOVEL EXCERPTS Chimera Mira Grant NONFICTION Artist Showcase: John Brosio Henry Lien Book Reviews Sunil Patel Interview: Ernest Cline The Geek’s Guide to the Galaxy AUTHOR SPOTLIGHTS Rahul Kanakia Karen Joy Fowler Brian Stableford Helena Bell Caroline M. Yoachim Toh EnJoe Kameron Hurley Kenneth Schneyer Elizabeth Hand MISCELLANY Coming Attractions Upcoming Events Stay Connected Subscriptions and Ebooks About the Lightspeed Team Also Edited by John Joseph Adams © 2015 Lightspeed Magazine Cover by John Brosio www.lightspeedmagazine.com Editorial, November 2015 John Joseph Adams | 712 words Welcome to issue sixty-six of Lightspeed! Back in August, it was announced that both Lightspeed and our Women Destroy Science Fiction! special issue specifically had been nominated for the British Fantasy Award. (Lightspeed was nominated in the Periodicals category, while WDSF was nominated in the Anthology category.) The awards were presented October 25 at FantasyCon 2015 in Nottingham, UK, and, alas, Lightspeed did not win in the Periodicals category. But WDSF did win for Best Anthology! Huge congrats to Christie Yant and the rest of the WDSF team, and thanks to everyone who voted for, supported, or helped create WDSF! You can find the full list of winners at britishfantasysociety.org. -

Renovation a Con Report by Evelyn C

Renovation A con report by Evelyn C. Leeper Copyright 2013 by Evelyn C. Leeper Table of Contents: l Getting There l Hotels l Registration l The Green Room l The Dealers Room l Exhibits l Art Show l Publications l Programming l A Trip to the Creation Museum l Designing Believable Physics l Done to Death: Program Topics That Have Out-Stayed Their Welcome l Before the Boom: Classic SF, Fantasy & Horror Movies Before 2001 & Star Trek l Short Films l The 1960s, 50 Years On l And the Debate Rages On: The Fanzine and Semi-Prozine Hugo Categories l Short but Containing the World: A Look at Novellas l Collaborative Fan Editing l Understanding Casino Gambling l The Autumn of the Modern Ages l Earth Abides: After We're Gone l Sidewise Awards l The Hidden Monkey Wrench in Cloning l The Solar System and SF: Setting SF on the Planets We Know l The Rode of the Science Adviser l The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction: A Q&A Session with the Editor l The Future of Cities l Masquerade l SF Physics Myths l Historical Figures in Action! l From the Earth to the Moon by Jules Verne l SF: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow l Still Fresh: Why Philip K. Dick is Still Relevant l The Future in Physics: How Close Are We to Time Travel or Breaking the Light Barrier? l Hugo Awards Ceremony l Radio Free Albemuth l Miscellaneous Getting There Renovation was held Wednesday, August 17, through Sunday, August 21, 2011, in Reno, Nevada. -

229 INDEX © in This Web Service Cambridge

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05246-8 - The Cambridge Companion to: American Science Fiction Edited by Eric Carl Link and Gerry Canavan Index More information INDEX Aarseth, Espen, 139 agency panic, 49 Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein (fi lm, Agents of SHIELD (television, 2013–), 55 1948), 113 Alas, Babylon (Frank, 1959), 184 Abbott, Carl, 173 Aldiss, Brian, 32 Abrams, J.J., 48 , 119 Alexie, Sherman, 55 Abyss, The (fi lm, Cameron 1989), 113 Alias (television, 2001–06, 48 Acker, Kathy, 103 Alien (fi lm, Scott 1979), 116 , 175 , 198 Ackerman, Forrest J., 21 alien encounters Adam Strange (comic book), 131 abduction by aliens, 36 Adams, Neal, 132 , 133 Afrofuturism and, 60 Adventures of Superman, The (radio alien abduction narratives, 184 broadcast, 1946), 130 alien invasion narratives, 45–50 , 115 , 184 African American science fi ction. assimilation of human bodies, 115 , 184 See also Afrofuturism ; race assimilation/estrangement dialectic African American utopianism, 59 , 88–90 and, 176 black agency in Hollywood SF, 116 global consciousness and, 1 black genius fi gure in, 59 , 60 , 62 , 64 , indigenous futurism and, 177 65 , 67 internal “Aliens R US” motif, 119 blackness as allegorical SF subtext, 120 natural disasters and, 47 blaxploitation fi lms, 117 post-9/11 reformulation of, 45 1970s revolutionary themes, 118 reverse colonization narratives, 45 , 174 nineteenth century SF and, 60 in space operas, 23 sexuality and, 60 Superman as alien, 128 , 129 Afrofuturism. See also African American sympathetic treatment of aliens, 38 , 39 , science fi ction ; race 50 , 60 overview, 58 War of the Worlds and, 1 , 3 , 143 , 172 , 174 African American utopianism, 59 , 88–90 wars with alien races, 3 , 7 , 23 , 39 , 40 Afrodiasporic magic in, 65 Alien Nation (fi lm, Baker 1988), 119 black racial superiority in, 61 Alien Nation (television, 1989–1990), 120 future race war theme, 62 , 64 , 89 , 95n17 Alien Trespass (fi lm, 2009), 46 near-future focus in, 61 Alien vs. -

Programming Participants' Guide and Biographies

Programming Participants’ Guide and Biographies Compliments of the Conference Cassette Company The official audio recorders of Chicon 2000 Audio cassettes available for sale on site and post convention. Conference Cassette Company George Williams Phone: (410) 643-4190 310 Love Point Road, Suite 101 Stevensville MD 21666 Chicon. 2000 Programming Participant's Guide Table of Contents A Letter from the Chairman Programming Director's Welcome................................................... 1 By Tom Veal A Letter from the Chairman.............................................................1 Before the Internet, there was television. Before The Importance of Programming to a Convention........................... 2 television, there were movies. Before movies, there Workicon Programming - Then and Now........................................3 were printed books. Before printed books, there were The Minicon Moderator Tip Sheet................................................... 5 manuscripts. Before manuscripts, there were tablets. A Neo-Pro's Guide to Fandom and Con-dom.................................. 9 Before tablets, there was talking. Each technique Chicon Programming Managers..................................................... 15 improved on its successor. Yet now, six thousand years Program Participants' Biographies................................................... 16 after this progression began, we humans do most of our teaching and learning through the earliest method: unadorned, unmediated speech. Programming Director’s Welcome -

The Devniad Book 75B Un Zine De Bob Devney 25 Johnson Street, North Attleboro, MA 02760 U.S.A

The Devniad Book 75b un zine de Bob Devney 25 Johnson Street, North Attleboro, MA 02760 U.S.A. Subscribe via e-mail to [email protected] For APA:NESFA #376 September 2001 copyright 2001 by Robert E. Devney Oh, I already had a migraine going, I Orbita Dicta can’t take any more of this! Heard in the Halls of The Millennium Philcon [In the longish registration line Thursday morn, (The 59th Annual World Science Fiction editor David G. Hartwell proffers a good-natured Convention/The 2001 Worldcon) joke about one of the truly giant figures of at the Pennsylvania Convention Center & modern SF, long-time Asimov's editor Gardner Philadelphia Marriott Hotel Dozois] Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.A. I have a line for you: Did you hear we're August 30-September 3, 2001 roasting Gardner Dozois? Think he can feed the whole crowd? Return with me now to the thrilling days of yesteryear, or at least early September, [I like that one well enough to submit it to the when things all seemed just a little less convention newsletter, which will run it and serious … several other quotes gathered under my byline throughout the con, boosting this reporter's already healthy ego … and setting me up for the [At the office, my boss David Izzi offers the inevitable fall, of which more anon] traditional clueless sci-fi send-off] So what time does the shuttle have lift- [Fan writer Mark Leeper shares my disgust off? when we see the tiny type on the convention's name badges, which after all will blight [At Logan Airport, as airline guy trundles by a thousands of fannish social interactions per day; blue two-wheeled rolling chair featuring straps but he's not so wroth at the screwup he can't and very high back; my brother Michael is joke about it] freaked] Hard for anyone to claim he's a BNF My God, Lecter must be coming with us! now … Of course, the biggest name fan I ever knew was George Vokelsoveljevic. -

Terra Fantastica

ñâåòà íà íàãðàäèòå ü Íàãðàäèòå “Õþãî” • Äèëÿí Áëàãîâ • Õþãî å ïî÷òè íåèçìåííî Îò 1988 ã. ðàêåòàòà å âúðõó òðè- èçïîëçâàíèÿò òåðìèí, â ÷åñò íà íàéñåòèí÷îâ êåðàìè÷åí ñòúëá îò Õþãî Ãåðíñáåê, çà îáîçíà÷àâàíå îãúí è å ìîíòèðàíà âúðõó ìðàìî- íà Íàãðàäàòà çà íàó÷íîôàíòà- ðåí äèñê. Ñòàòóåòêàòà å äúëãà îêî- ñòè÷íî ïîñòèæåíèå, êîåòî å îôè- ëî 75 ñì. è òåæè 5,5 êã. öèàëíèÿò âàðèàíò íà èìåòî é îò Ñðåä íàãðàäèòå, äàâàíè â îá- 1958 ã. íàñàì. Çà ïúðâè ïúò íàãðà- ëàñòòà íà íàó÷íàòà ôàíòàñòèêà, äè Õþãî ñà äàäåíè íà XI Ñâå- Õþãî ñà óíèêàëíè â åäèí ñúùå- òîâåí êîíãðåñ ïî íàó÷íà ôàíòàñ- ñòâåí àñïåêò. Âñè÷êè äðóãè íàé- òèêà (the World Science Fiction ïðåñòèæíè íàãðàäè (ðàçáèðà ñå, Convention), ñúêðàòåíî íàðè÷àíà â àíãëîåçè÷íèòå ñòðàíè) - Íåáþ- Óúðëäêîí (WorldCon), ïðåç 1953 ëà, Ôèëèï Ê.Äèê, Òåîäîð ã. âúâ Ôèëàäåëôèÿ; ñëåä òîâà èäå- Ñòúðäæúí, Àðòúð ×. Êëàðê è ÿòà å èçîñòàâåíà çà åäíà ãîäèíà Äæîí Ó. Êåìïáúë Ìåìîðèúë - (1954), íî îò 1955 ã. íàñàì íàãðà- ñå ïðèñúæäàò îò ðàçëè÷íè êàòå- äèòå ñà åæåãîäíè. Îðèãèíàëíàòà ãîðèè ïðîôåñèîíàëíè ÷èòàòåëè - èäåÿ, äîøëà îò ôåíà Õàë Ëèí÷, å ïèñàòåëè, àêàäåìèöè èëè ñïåöè- ïî÷åðïåíà îò Íàãðàäèòå íà Íàöè- àëíî æóðè - äîêàòî îñíîâíîòî îíàëíàòà ôèëìîâà àêàäåìèÿ (ò. êîëè÷åñòâî ãëàñîâå çà Õþãî íàð. Îñêàðè). Íàãðàäàòà å ñ ôîð- âèíàãè ïðèíàäëåæè íà îáèêíîâå- ìàòà íà ðàêåòà, èçïðàâåíà îòâåñ- íèòå ÷èòàòåëè - àìàòüîðè è ôå- íî âúðõó âåðòèêàëíèòå ñè ñòàáè- íîâå. ëèçàòîðè. Ïúðâèÿò ìîäåë å ïðî- Íàãðàäèòå ñà ðàçïðåäåëåíè â åêòèðàí è èçðàáîòåí îò Äæåê íÿêîëêî êëàñà, êîèòî îò ãîäèíà íà ÌàêÍàéò; îò 1955 ã. -

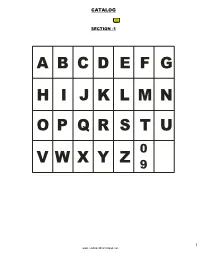

Page 1 CATALOG SECTION -1 a B C D E F G H I J K L M N O

CATALOG SECTION -1 ABCD EFG H I JKLMN OPQR STU 0 VWX Y Z 9 1 www.lendingelibrary.tripod.com SECTION -2 TITLES PAGE NO. (EBOOKS) HARRY POTTER 1-6 (EBOOKS) THE COMPLETE CONSPIRACY - 89 EBOOKS 3 BEGINNER DRAWING EBOOKS 3 EBOOKS FOR MAKING CASH 12 HYPNOSIS EBOOKS 15,000+EBOOKS+AUTOMATION 20 ENGLISH-LEARNING EBOOKS 22 EBOOKS ON JOBS RESUMES INTERVIEWS 24 ISLAMIC EBOOKS BY FISABILILLAH PUBLICATIONS 32 FOREX EBOOKS COLLECTION 43 UML AND MDA EBOOKS AND SEVERAL TUTORIALS 32 MUST HAVE HACKERS EBOOKS 49 HEALTH EBOOKS - INC SEX - SMOKING - SKIN – HAIR 57 COOKING E-BOOKS 70 SEXUAL E-BOOKS 82 NEW EBOOKS WITH RESALE 98 DOT NET EBOOKS 126_ORACLE_BOOKS(GREATEST_COLLECTION) 181 EBOOKS ON HEALTH,PERSONAL FINANCE,NUTRITION EDUCATION, ETC A BATCH OF PHYSICS EBOOKS (MECHANICS, QUANTUM, CHEMISTRY, THERMODYNAMICS,), PROBLEMS AND FORMULAS A COLLECTION OF 155 BUSINESS EBOOKS 2 www.lendingelibrary.tripod.com A FEW ENCYCLOPEDIAS A_COLLECTION_OF_FITNESS,_WEIGHTLIFTING,_STRETCHING_EBOOKS ADOBE CS2 EBOOKS ALEISTER CROWLEY RARE COLLECTION AMAZING_PALMISTRY_SECRETS ANNE RICE ARIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE A-Z NON-FICTION BIOTECNOLOGIE EBOOKS PACK2 BIOTECNOLOGIE EBOOKS PACK7 BOOKS[MATHCAD,ANSYS,SOLIDEDGE] BOOKS-MATHS BOTANY EBOOKS CHESS EBOOKS CHESS PROBLEMS & STUDIES BY SUPERKASP CHILDCARE CIRCUITS COMICS COLLECTIONS VOL-1,2,3,4 CISCO REFERENCE SUITE COMICS-ADVENTURES OF TINTIN-THE COMPLETE COLLECTON OF TINTIN- EBOOKS COMPLETE HOME - HOW TO GUIDES 158IN1 (AIO) - EBOOK PDF - DO IT YOURSELF GUIDES COMPTIA A+ CERTIFICATION EBOOKS COMPUTER EBOOKS CD 3 www.lendingelibrary.tripod.com -

Global Science Fiction Syllabus Spring 2012 1.Docx

[CRN: 26042] ENGL 3325: Global Science Fiction (ADVANCED READINGS IN WORLD LITERATURE) Class Meetings: 6 – 7:20 T, TH in Irby Hall 304 Instructor: Dr. Isiah Lavender, III Office: 401 Irby Hall Office Hours: MWF 10-12; TTH 11-1, and by appointment Phone, E-mail & Facebook: (501) 450-5118; [email protected] BOOKS: Available at UCA Bookstore Bell and Molina-Gavilan, eds. Cosmos Latinos: An Anthology of Science Fiction from Latin America and Spain. Evans et al., eds. The Wesleyan Anthology of Science Fiction. Hopkinson and Mehan, eds. So Long Been Dreaming: Postcolonial Science Fiction & Fantasy. Seed. Science Fiction: A Very Short Introduction. Course Description: This course will consider five major themes in science fiction: alien encounters, time travel and alternative history, dystopian projections, evolution and environment as well as gender and sexuality. The particular works of science fiction upon which this course focuses all explore the question of what it means to be human. What does each work have to say about what it means to be human? For instance, where is the dividing line between human and non-human: animal, machine, artificial intelligence, created being, alien, clone, etc. What are the ethical, philosophical, and/or moral implications the work raises concerning these issues? How are these questions relevant in metaphorical terms to the world we live in? With these questions in mind, science fiction imagines situations that are estranged from our world and that are also reflections of the world in which they were written. Consequently, we will attempt to tie examples of science fiction to different historical moments, in order to demonstrate how science fiction has evolved over time in response to the modern technological environment and identity politics. -

EDITOR EXTRAORDINAIRE Gardner Dozois Was a Pretty Amazing Science Fiction Editor

EDITORIAL Sheila Williams EDITOR EXTRAORDINAIRE Gardner Dozois was a pretty amazing science fiction editor. There are fifteen best ed - itor Hugos to prove it and other evidence as well. During his nineteen years at the helm of Asimov’s, he placed 164 stories on the final Hugo ballot. Although there were ups and downs, this figure averages out to more than eight stories per year. Thirty- five of these tales took home the rocket ship. While I haven’t counted the Nebula nominees, I know that during his editorship he purchased fifteen works that re - ceived that prestigious award. Long before he became editor of this magazine, Gardner had shown a knack for uncovering the diamonds in the stacks of submissions at various magazines. In the early seventies, he convinced Ejler Jakobsson to purchase first stories by Connie Willis and George R.R. Martin. During his tenure as editor of Asimov’s, first sales to the mag - azine included Kage Baker, Tony Daniel, and Mary Rosenblum. MacArthur Fellows “Genius Grant” winners Kelly Link and Jonathan Lethem both made their first pro - fessional story sales to Gardner as well. Yet, Gardner never took any of his or the magazine’s awards or other successes for granted. Whenever there was an award ceremony, whether out of respect for the oth - er finalists, his innate pessimism, or both, he could work out a scenario in which every single Asimov’s nominee—including him—would lose the award. He even managed to do this on the two occasions when Asimov’s was responsible for every nominee in a par - ticular category (novelette in 1996 and novella in 1997). -

Table of Contents

L.A.con III 1996 A convention report by Evelyn C. Leeper (with appendix by Mark R. Leeper) Copyright 1996 Evelyn C. Leeper and Mark R. Leeper Table of Contents Introduction Convention Center Registration/Program Books/Etc Art Show Programming Overlooked Books and Overrated Novels Religion In SF Books and Movies Miscellaneous Overrated Films and Overlooked Movies The Future Of Religion Funny Stories From Science Research and Development Dinosaurs The Retro-Hugo Award Ceremony Treks Not Taken Parties (Friday) Death of the Book Alternate Histories In Reality Style Vs. Substance Nanotechnology Do We Need A New Definition Of Literacy? Is The Scientific Method The Death Of God? GHOST IN THE SHELL The L.A.con III Masquerade Parties (Saturday) Reading: James Morrow Gender Roles: What Makes A Tiptree Award Winner James White Reception Life on Mars Why Is Fandom So White? Why Is Science Fiction So White? The Hugo Awards Ceremony Parties (Sunday) Images of Mars Debate: There Are Some Things Man Was Not Meant to Know Miscellaneous Film Presentations at L.A.con III by Mark R. Leeper Introduction L.A.con III, the 54th World Science Fiction Convention, was held from 29 August through 2 September 1996 in Anaheim, California. There were approximately 6531 people attending. L.A.con III did not start auspiciously for us. We were scheduled on a 5:15 PM non-stop from Newark to Los Angeles, but United called us at about 1 PM to tell us that flight was canceled. After some negotiation ("No, we don't want to leave from Kennedy") we ended up on a 5:05 PM flight to Denver, connecting after an hour lay-over with a flight to Los Angeles.