Thailand Monitor 2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thailand Singapore

National State of Oceans and Coasts 2018: Blue Economy Growth THAILAND SINGAPORE National State of Oceans and Coasts 2018: Blue Economy Growth THAILAND National State of Oceans and Coasts 2018: Blue Economy Growth of Thailand July 2019 This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes or to provide wider dissemination for public response, provided prior written permission is obtained from the PEMSEA Executive Director, acknowledgment of the source is made and no commercial usage or sale of the material occurs. PEMSEA would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale, any commercial purpose or any purpose other than those given above without a written agreement between PEMSEA and the requesting party. Published by Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA). Printed in Quezon City, Philippines PEMSEA and Department of Marine and Coastal Resources (DMCR, Thailand). 2019. National State of Oceans and Coasts 2018: Blue Economy Growth of Thailand. Partnerships in Environmental Management for the Seas of East Asia (PEMSEA), Quezon City, Philippines. 270 p. ISBN 978-971-812-056-9 The activities described in this report were made possible with the generous support from our sponsoring organizations - the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The contents of this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of PEMSEA Country Partners and its other participating organizations. The designation employed and the presentation do not imply expression of opinion, whatsoever on the part of PEMSEA concerning the legal status of any country or territory, or its authority or concerning the delimitation of its boundaries. -

Oyster Salinity-Based Habitat Monitoring in Bandon Bay, Surat Thani, Thailand: a Coupled Eco-Hydrological Model Approach

ESEARCH ARTICLE R ScienceAsia 46 (2020): 93–101 doi: 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2020.010 Oyster salinity-based habitat monitoring in Bandon Bay, Surat Thani, Thailand: A coupled eco-hydrological model approach a a,b, b,c Kalanyu Sunthawanic , Kornkanok Bunwong ∗, Wichuta Sae-jie a Department of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, Mahidol University, Ratchathewi, Bangkok 10400 Thailand b Centre of Excellence in Mathematics, CHE, Bangkok 10400 Thailand c Department of Applied Mathematics and Informatics, Faculty of Science and Industrial Technology, Prince of Songkla University, Surat Thani Campus, Surat Thani 84000 Thailand ∗Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Received 16 Jul 2019 Accepted 23 Jan 2020 ABSTRACT: Bandon Bay in Surat Thani Province, Thailand, is one of the most productive aquaculture for oysters. In order to monitor a suitable area for oyster culture related to salinity, a coupled ecological and hydrodynamical model was constructed to describe the interaction between biological and physical processes in estuarine and coastal environments. The oyster food web is modified from the classical NPZ model in which the region of attraction, the existence of equilibrium points, their asymptotic stability conditions, and the non-existence of closed orbit were analyzed. The Princeton Ocean Model with monthly mean surface wind and river discharge was employed for ocean circulation. Finally, numerical simulation has revealed the interrelation between oyster population and their salinity- based habitat, with an output that quantify the consequences for oyster density, leading to suitable oyster culture areas possibly located around the mouths of Tha Chana canal and Thatong canal. KEYWORDS: coupled model, ecological model, hydrodynamic model, oyster, salinity MSC2010: 00A71 34A34 34C60 65M06 INTRODUCTION around the river mouth. -

Title a Study of Living Conditions in Post-Tsunami Houses: the Case of the Moklen Ethnic Minority in Phang Nga Province, Souther

A Study of Living Conditions in Post-Tsunami Houses: The Title Case of the Moklen Ethnic Minority in Phang Nga Province, Southern Thailand( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Monsinee, Attavanich Citation 京都大学 Issue Date 2016-09-23 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k20040 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion ETD Kyoto University A Study of Living Conditions in Post-Tsunami Houses: The Case of the Moklen Ethnic Minority in Phang Nga Province, Southern Thailand September 2016 Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies Kyoto University Doctoral Course in Environmental Management MONSINEE ATTAVANICH A Study of Living Conditions in Post-Tsunami Houses: The Case of the Moklen Ethnic Minority in Phang Nga Province, Southern Thailand A Thesis submitted for the fulfillment of the Doctor Degree of Global Environmental Management by MONSINEE ATTAVANICH Laboratory of Global Environmental Architecture Graduate School of Global Environmental Studies Kyoto University, Japan 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to acknowledge and express my deep appreciation to organizations and people who support and encourage for the completion of this dissertation. Firstly, I would like to give my gratitude to the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sport, Science and Technology of Japan and environmental management Leader Program of Kyoto University for providing scholarship to facilitate my study in the Graduate school of Global Environmental Studies, Kyoto University; Assoc.Prof. Kobayashi Hirohide, who is the advisor for every support not only for this research but for the future of work. Prof. Okazaki Kenji who is the co-advisor for support and giving not only useful comments but helpful suggestions to improve this research in other perspectives. -

An Updated Checklist of Aquatic Plants of Myanmar and Thailand

Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Taxonomic paper An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand Yu Ito†, Anders S. Barfod‡ † University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand ‡ Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark Corresponding author: Yu Ito ([email protected]) Academic editor: Quentin Groom Received: 04 Nov 2013 | Accepted: 29 Dec 2013 | Published: 06 Jan 2014 Citation: Ito Y, Barfod A (2014) An updated checklist of aquatic plants of Myanmar and Thailand. Biodiversity Data Journal 2: e1019. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.2.e1019 Abstract The flora of Tropical Asia is among the richest in the world, yet the actual diversity is estimated to be much higher than previously reported. Myanmar and Thailand are adjacent countries that together occupy more than the half the area of continental Tropical Asia. This geographic area is diverse ecologically, ranging from cool-temperate to tropical climates, and includes from coast, rainforests and high mountain elevations. An updated checklist of aquatic plants, which includes 78 species in 44 genera from 24 families, are presented based on floristic works. This number includes seven species, that have never been listed in the previous floras and checklists. The species (excluding non-indigenous taxa) were categorized by five geographic groups with the exception of to reflect the rich diversity of the countries' floras. Keywords Aquatic plants, flora, Myanmar, Thailand © Ito Y, Barfod A. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Do You Want to Travel Different? 50 Great Great 50 Green Escapes Green Become a Green Traveller Today

THAILAND DO YOU WANT TO TRAVEL DIFFERENT? 50 GREAT GREEN ESCAPES BECOME A GREEN TRAVELLER TODAY By visiting the destinations highlighted in this guidebook, and by reporting your impressions and comments to www.tourismthailand.org/7greens you will help the Tourism Authority of Thailand promote and preserve the country’s natural wonders. THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT. Become a Green Traveller Today Tourism Authority of Thailand Published and distributed by Tourism Authority of Thailand Attractions Promotion Division Product Promotion Department. Editor: Richard Werly / AsieInfo Ltd, ITF Silom Palace, 163/658 Silom Road, Bangkok 10500. Producer: Titaya Jenny Nilrungsee Assistant editor: Thanutvorn Jaturongkavanich Assistant producer: Janepoom Chetuphon Design & Artwork: Tistaya Nakneam Writer: Chandra Hope Heartland Special Thanks: Simon Bowring, TAT Photo Bank, Solomon Kane Copyright © 2010 Tourism Authority of Thailand. Thailand Tourism Awards (www.tourismthailand.org/tourismawards) All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any other information storage and retrieval system without prior permission in writing from Tourism Authority of Thailand. ISBN: 978-974-679-200-4 Printed in Thailand by Amarin Printing and Publishing Public Company Limited. Seven The production of this book was done in strict compliance with forward thinking environmental the initiatives from the team. It was created using recyclable environmentally -

26178938.Pdf

Thappud Sarasin Bridge Khao Lak Ao Luk Yacht haven Marina Thepkassatri Road Andanman Sea Water Village Kok Kloi James Bond Island Sak Cape Khao Phanom Mai Khao Phang-Nga Bay Beach Phuket Int’l Airport National Park Khao Phanom Benja National Park Koh Hong Thai Rat Cape Sirinath Huay To Waterfall National Park Blue Canyon Kung Bay Koh Panak Nai Yang Beach Mission Hills d a Sai Cape o R i r Helipad t a s Ao Po Grand Marina s a Koh Yao Noi k Koh Reat p e Krabi Airport h T Naithon Beach Kho Phra Taew National Park Po Bay Thalang Bang Pae Waterfall Krabi City Nua Klaong Koh kala Ton Sai Waterfall Layan Phuket T h Layan Beach e Airpark p Bang Rong Bay k a s s Koh Yao Yai a Klong Thom t Ao Pranang ri R o a Paklok Bang Tao Beach Laguna d Phuket Koh Poda Heroines' Son Cape Monument Yamu Cape Island Koh Kai Cherngtalay Srisoonthorn Road Surin Beach Sing Cape Tha Ruea Boat Lagoon Marina Koh Si Bo Ya Royal Phuket Marina Kamala Beach Koh Rang Yai Tha Ruea Bay Hua Lan Cape Hin Koh Yung d Koh Phai a Cape o Koh Maphrao R Kathu Waterfall s s Loch Palm a P y Koh Pu B Sapam Tourist Thepkassatri Road Police Kalim Beach d Kathu Ph oa ra Baramee R Koh Phi Phi Don Patong Beach Phuket Country Club Homeworks Koh Koh Phi Phi Le Bang Wad Dam Phuket Sire King Rama Freedom Bay IX Park City Copyright Ltd 2004© Image Co Events Asia Sakdidej Kwang VichitRd. -

Draft Environmental Report on Thailand

DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL REPORT ON THAILAND PREPARED BY THE SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY DIVISION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. AID/DS/ST CONTRACT NO, SA/TOA 1-77 WITH U.S. MAN AND THE BIOSPHERE SECRETARIAT DEPARTMENT OF STATE WASHINGTON, D.C. OCTOBER 1979 DRAFT ENVIRONMENTAL PROFILE OF THAILAND Table of Contents Section page Introduction and Summary ii 1.0 Populat i h,ht'<eristics 1.1 Get i I p ition statistics .................................. 1 1.2 Sp i 1 ibution ........................................... 2 1.3 Ethr .."d religion ......................................... 6 1.4 Education ............ ......................................... 7 1.5 Health ........................................................ 8 1.6 Birth control and population policy.............................9 2.0 The Economy 2.1 General economic statistics .................................... 11 2.2 Economic structure and growth .................................. 13 3.0 Resources and Environmental Problems 3.1 Topography and climate ......................................... 17 3.2 Freshwater ..................................................... 21 3.3 Soils .......................................................... 26 3.4 Minerals ....................................................... 28 3.5 Forests ........................................................ 30 3.6 Coastal zone ................................................... 35 3.7 Wildlife ....................................................... 38 3.8 Fisheries ..................................................... -

Brotia Costula

The Biological and Ecology Study of Brotia costula at Lam Liang Brook, Kong Ra District, Srinakarin District, Phatthalung Province, Thailand Natrawee Setthasuk, Natthanicha Samanchat, Supissara Bualoi Advisors: Hamwan Yockchawee Princess Ubolratana Rajakanya’s College Phatthalung 557 Khuhasawan Sub-District, Muang District, Phatthalung Province, Thailand 93000 Abstract depth (25.63a3.09 cm) and DO Of water (6.97-0.33 mg/L) Key Brotia costulas are freshwater snails arranged in the words: Brotia costula, Biology. Ecology, Lam Liang Brook Pacliychilidae family, were continuously decreasing. The project Introduction of biology and ecology of Brotia costulas at Lam Liang Brook, Phatthalung Province has an area on the east side Kong Ra District and Srinskarin District, Phatthalung Province to that connects to Songkhla Lake, the west side is Banthat studied about their morphology including width, length, mountain in Pa Bon district, Kong Ra district and Si perimeter, weight and environmental factors. In case of biology, Banpot district, has plentifully forest which is an plants, animals and physical factors such as soil analyzing, air temperature, water temperature, pH, water depth and DO or water important source of water for various rivers, such as were mentioned in each stations for analyzing the variation and Phraiwan Waterfall, Nora Waterfall, and Ton Waterfall, comparing the mean using DMRT, The study indicated that the which is an important tourist destination of Phatthalung Brotia costula is a rough single cover shellfish and it has dark Province, that area contributes agriculture to rubber brown color, There are parallel lines along the length of the body plantation and fruit plantation from observation of loops, and all 5 loops are connected to each other, The shell of organisms living in the watersheds found that there are Brotia costula is twisted in a right spiral style, the pointed spike diversity, such as shrimp, crab, fish of each species, is closed. -

A New Forest-Dwelling Bent-Toed Gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae: Cyrtodactylus) from Doi Suthep, Chiang Mai Province, Northern Thailand

Zootaxa 3811 (2): 251–261 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3811.2.6 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:E778FA4E-D8E5-440A-8EAE-BCBA2CFBD24B A new forest-dwelling Bent-toed Gecko (Squamata: Gekkonidae: Cyrtodactylus) from Doi Suthep, Chiang Mai Province, northern Thailand KIRATI KUNYA1, AUMPORN PANMONGKOL2, OLIVIER S. G. PAUWELS3, MONTRI SUMONTHA4, JIRAPORN MEEWASANA2, WORAPHOT BUNKHWAMDI5 & SIRIWAT DANGSRI6 1Nakhonratchasima Zoo, 111 M. 1, Ratchasima-Pak Tongchai Rd., Chaimongkol, Muang, Nakhonrajsima 30000, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] 2Doi Suthep-Pui National Park, Suthep, Muang, Chiang Mai 52000, Thailand 3Département des Vertébrés Récents, Institut Royal des Sciences naturelles de Belgique, Rue Vautier 29, B-1000 Brussels, Belgium. E-mail: [email protected] 4Ranong Marine Fisheries Station, 157 Saphanpla Rd., Paknam, Muang, Ranong 85000, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] 5Lanna Bird and Nature Conservation Club, 76/1 M. 14, Soi 5, Suthep Rd., Chiang Mai 52000, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] 6Ronphibun Hospital, Ronphibun District, Nakhon Si Thammarat 80130, Thailand Abstract We describe a new forest-dwelling Cyrtodactylus from Doi Suthep, Chiang Mai Province, northern Thailand. Cyrtodac- tylus doisuthep sp. nov. is characterized by a maximal known SVL of 90.5 mm; 19 or 20 longitudinal rows of dorsal tu- bercles; a continuous series of 34 or 35 enlarged femoro-precloacal scales, including six or seven pitted scales on each femur (male and females) separated by a diastema from six pitted (females) or pore-bearing (male) precloacal scales; no precloacal groove or depression; transversely enlarged subcaudal scales; and six or seven irregular thin beige dorsal bands between limb insertions. -

Comparative Destination Vulnerability Assessment for Khao Lak, Patong Beach and Phi Phi Don

SEI - Africa Institute of Resource Assessment University of Dar es Salaam P. O. Box 35097, Dar es Salaam Tanzania Tel: +255-(0)766079061 SEI - Asia 15th Floor, Witthyakit Building 254 Chulalongkorn University Chulalongkorn Soi 64 Phyathai Road, Pathumwan Bangkok 10330 Thailand Tel+(66) 22514415 Stockholm Environment Institute, Project Report - 2009 SEI - Oxford Suite 193 266 Banbury Road, Oxford, OX2 7DL UK Tel+44 1865 426316 SEI - Stockholm Kräftriket 2B SE -106 91 Stockholm Sweden Tel+46 8 674 7070 SEI - Tallinn Lai 34, Box 160 EE-10502, Tallinn Estonia Tel+372 6 276 100 SEI - U.S. 11 Curtis Avenue Somerville, MA 02144 USA Tel+1 617 627-3786 SEI - York University of York Heslington York YO10 5DD UK Tel+44 1904 43 2897 The Stockholm Environment Institute Comparative Destination Vulnerability Assessment for SEI is an independent, international research institute.It has been Khao Lak, Patong Beach and Phi Phi Don engaged in environment and development issuesat local, national, regional and global policy levels for more than a quarterofacentury. Emma Calgaro, Sopon Naruchaikusol, and Kannapa Pongponrat SEI supports decision making for sustainable development by bridging science and policy. sei-international.org Comparative Destination Vulnerability Assessment for Khao Lak, Patong Beach and Phi Phi Don Sustainable Recovery and Resilience Building in the Tsunami Affected Region Emma Calgaro, Sopon Naruchaikusol, and Kannapa Pongponrat (1) Department of Environment and Geography, Macquarie University, Sydney (2) Stockholm Environment Institute -

WEPA Outlook on Water Environmental Management in Asia 2012

Ministry of the Environment WEPA Outlook on 2012 Water Environmental Management WEPA Outlook on Water Environmental Management in Asia 2012 Water Environment Partnership in Asia (WEPA) Ministry of the Environment, Japan Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) Outlook on Water Environmental Management in Asia 2012 Copyright © 2012 Ministry of the Environment, Japan. All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from Ministry of the Environment Japan through the Institute for Global Environment Strategies (IGES), which serves as the WEPA Secretariat. ISBN: 978-4-88788-108-2 This publication is made as a part of WEPA and published by the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES). Although every effort is made to ensure objectivity and balance, the publication of study results does not imply WEPA partner country’s endorsement or acquiescence with its conclusions. Ministry of the Environment, Japan 1-2-2 Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, 100-8795, Japan Tel: +81-(0)3-3581-3351 http://www.env.go.jp/en/ Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) 2108-11 Kamiyamaguchi, Hayama, Kanagawa, 240-0115, Japan Tel: +81-(0)46-855-3700 http://www.iges.or.jp/ The research team for WEPA Outlook 2012 includes the following IGES members: [Drafting team] Yatsuka Kataoka, Director, Freshwater Sub-group Tetsuo Kuyama, -

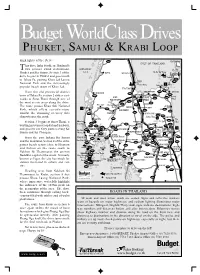

Phuket &Krabi Loop

Budget WorldClass Drives PHUKET, SAMUI & KRABI LOOP Highlights of the Drive 4006 KO PHANGAN G U L F O F T H A I L A N D his drive links Southern Thailand’s T two premier island destinations, A N D A M A N Ban Chaweng Mu Ko Ang Thong Phuket and Ko Samui. Section 1 of the S E A KAPOE THA CHANA KO SAMUI drive begins in Phuket and goes north Ban Nathon to Takua Pa, passing Khao Lak Lamru 4169 CHAIYA 4170 National Park and the increasingly Phum Riang 4 Ferry popular beach resort of Khao Lak. DON SAK THA CHANG 4142 From the old provincial district KANCHANADIT 4142 KHANOM KURA BURI 41 PHUNPHIN 4232 town of Takua Pa, section 2 strikes east- 4 401 4014 Hat Nai KHIRI SURAT 4010 wards to Surat Thani through one of RATTANIKHOM THANI Phlao 401 3 the most scenic areas along the drive. 4134 4100 Khao Sok Rachaphrapha 41 The route passes Khao Sok National KHIAN SA SICHON TAKUA PA Dam SAN NA DOEM 2 401 4106 Park, which offers eco-adventure BAN TAKHUN 4009 401 4133 amidst the stunning scenery that 4032 PHANOM BAN NA SAN 4188 4186 characterises the park. Krung Ching NOPPHITAM KAPONG 415 4140 THA Khao Lak WIANG SA (roads closed) SALA Section 3 begins at Surat Thani, a 4090 Lam Ru 4035 PHRA PHIPUN 4141 bustling provincial capital and harbour, 4240 4090 PHLAI PHRAYA 4016 4 4197 SAENG PHROMKHIRI 4013 4133 4015 5 and goes to car-ferry ports serving Ko 4 PHANG NGA 4035 CHAI BURI NAKHON SRI Hat Thai THAP PHUT 4228 Khao Samui and Ko Phangan.