Beothuk Skull Paper for JMC Revised

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada Canada De La

c FISHERIES AND MARINE SERVICE SERVICE DES P£CHES ET DES SCIENCES DE LA MER TECHNICAL REPORT No. 691 RAPPORT TECHNIQUE N° 1977 Environment Environnement I Canada Canada Fisheries Service des piches and Marine et des sciences Service de la mer Technical Reports Technical Reports are research documents that are of sufficient importance to be preserved, but which for some reason are not appropriate for primary scientific publication. Inquiries concerning any particular RepOlt should be directed to the issuing establishment. Rapports Techniques Les rapports techniques sont des documents de recherche qui revetent une assez grande importance pour etre conserves mais qui, pour une raison ou pour une autre, ne conviennent pas a une publication scientifique prioritaire. Pour toute demande de renseignements concernant un rapport particulier, i1 faut s'adresser au service responsable. Department of the Environment Ministere de 1'Environnement Fisheries and Marine Service Service des Peches et des Sciences de la mer Research and Development Directorate Direction du Recherche et Developpement • TECHNICAL REPORT No. 691 RAPPORT TECHNIQUE NO. 691 (Numbers 1-456 in this series (Les numeros 1-456 dans cette serie furent were issued as Technical Reports utilises comme Rapports Techniques de 1'office of the Fisheries Research Board of des recherches sur les p~cheries du Canada. Canada. The series name was changed Le nom de la serie fut change avec le with report number 457). rapport numero 457). • Limnology and Fish Populations of Red Indian Lake, a Multi-Use Reservoir by C.J. MORRY and L.J. COLE This is the forty-seventh Ceci est le quarante-septieme Technical Report from the Rapport Technique de la Direction du Research and Development Directorate Recherche et Developpement Newfoundland Biological Station Station biologique de Terre-Neuve St. -

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895

Newfoundland in International Context 1758 – 1895 An Economic History Reader Collected, Transcribed and Annotated by Christopher Willmore Victoria, British Columbia April 2020 Table of Contents WAYS OF LIFE AND WORK .................................................................................................................. 4 Fog and Foundering (1754) ............................................................................................................................ 4 Hostile Waters (1761) .................................................................................................................................... 4 Imports of Salt (1819) .................................................................................................................................... 5 The Great Fire of St. John’s (1846) ................................................................................................................. 5 Visiting Newfoundland’s Fisheries in 1849 (1849) .......................................................................................... 9 The Newfoundland Seal Hunt (1871) ........................................................................................................... 15 The Inuit Seal Hunt (1889) ........................................................................................................................... 19 The Truck, or Credit, System (1871) ............................................................................................................. 20 The Preparation of -

Introduction Since Time Immemorial, Human Beings Have Used Narrative

Chapter 1 – Introduction Since time immemorial, human beings have used narrative to help us make sense of our experience of life. From the fireside to the theatre, from the television and silver screen to the more recent manifestations of the virtual world, we have used storytelling as a means of providing structure, order, and coherence to what can otherwise appear an overwhelming infinity of random, unrelated events. In ordering the perceived chaos of the world around us into a structure we can grasp, narrative provides insight and understanding not only of events themselves, but on a more fundamental level, of the very essence of what it means to live as a human being. As the primary means by which historical writing is organized, narrative has attracted a large body of historians and philosophers who have grappled with its impact on our understanding of the past. Underlying their work is the tension between historical writing as a reflection of what took place in the past, and the essence of narrative as a creative, imaginative act. The very structure of Aristotelian narrative, with its causal link between events, its clearly defined beginning, middle and end, its promise of catharsis, its theme or moral, reflects an act of imagination on the part of its author. While an effective narrative first and foremost strives to draw us into its world of story and keep us there until the ending, the primary goal of historical writing, in theory at least, is to increase our understanding about the past. While these two goals are not inherently incompatible, they do not always work in concert. -

A Beothuk Skeleton

Edinburgh Research Explorer A Beothuk skeleton (not) in a glass case Citation for published version: Harries, J 2016, A Beothuk skeleton (not) in a glass case: rumours of bones and the remembrance of an exterminated people in Newfoundland - the emotive immateriality of human remains. in J-M Dreyfus & É Anstett (eds), Human remains in society: Curation and exhibition in the aftermath of genocide and mass- violence., 9, Human Remains and Violence, Manchester Univ. Press, Manchester. <http://www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk/9781526107381/> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Human remains in society General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 A Beothuk Skeleton (not) in a Glass Case: Rumours of Bones and the Remembrance of an Exterminated People in Newfoundland John Harries, Social Anthropology, The University of Edinburgh The emotive immateriality of human remains This chapter is about the human remains and how human remains inhabit the public sphere after their exhumation. -

Notice of Intent to Submit a Claim to Arbitration Under Chapter

NOTICE OF INTENT TO SUBMIT A CLAIM TO ARBITRATION UNDER CHAPTER ELEVEN OF THE NORTH AMERICAN FREE TRADE AGREEMENT ABITIBIBOWATER INC., Investor, v. GOVERNMENT OF CANADA, Party. Pursuant to Articles 1116, 1117, and 1119 of the North American Free Trade Agreement ("NAFTA"), the disputing Investor, AbitibiBowater Inc. (hereinafter "AbitibiBowater" or "the Company"), hereby respectfully serves a Notice ofIntent to Submit a Claim to Arbitration for breach by the Government of Canada (hereinafter "Canada"), through the actions of the provincial Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, of its obligations under Chapter Eleven ofNAFTA. AbitibiBowater also hereby requests Canada and the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador to begin formal consultations and negotiations, as contemplated by NAFTA Article 1118, in an effort to amicabiy resoive this dispute. Such consultations would be in accordance with the Company's proactive outreach to form a joint working group to address and resolve all issues related to its assets and rights in the Province of Newfoundland and Labrador. I. TYPE OF CLAIM 1. AbitibiBowater submits this Notice of Intent both under NAFTA Article 1116 as an investor on its own behalf, and under NAFTA Article 1117 on behalf of three investment enterprises that it owns or controls directly or indirectly: Abitibi-Consolidated Company of Canada, Abitibi-Consolidated Inc. and AbitibiBowater Canada Inc. (hereinafter collectively the "AbitibiBowater Canadian Entities"). II. DISPUTING INVESTOR 2. The disputing investor, AbitibiBowater Inc., is incorporated in the State of Delaware, United States of America, and thus is an enterprise of a Party (the United States) pursuant to NAFTA Article 1139. Its registered address is as follows: 1209 Orange Street Wilmington, Delaware 19801 United States of America Phone: 302-658-7581 Fax: 302-655-2480 III. -

GFW Community Profile Design Draft

Project Co‐ordinator: Gary Hennessey, Economic Development Officer Town of Grand Falls‐Windsor, NL Phone: 709‐489‐0483 / Fax: 709‐489‐0465 Email: [email protected] www.grandfallswindsor.com Project Facilitator: Kris Stone Research, Design & Layout By: Kris Stone Photos By: Kris Stone The Town of Grand Falls‐Windsor Grand Falls‐Windsor Heritage Society Up Sky Down Films Elmo Hewle MAYOR’S MESSAGE Welcome to the Grand Falls‐Windsor WCommunity Profile. This document has been created to showcase informaon on the many remarkable aspects that our community has to offer to current and potenal residents, as well as business owners. There are secons on demographics, aracons, events, tourism, community organizaons, the various types of businesses and industry in the area, as well as a lile bit of history on how our town got its start and became the municipality it is today. Grand Falls‐Windsor is the largest town in Central Newfoundland. The community is located along the banks of the Exploits River, seled within a serene valley atmosphere—a great place to live, work, and play. Its locaon also makes it a favourable place for doing business, as it is easily accessible from virtually all areas of the island. For this reason, Grand Falls‐Windsor has become known as a major service centre for Central Newfoundland and a hub for most of the island. Over the years our town connues to grow and prosper, with numerous housing developments steadily building family friendly neighbourhoods. There are many new and exisng businesses thriving and diversifying our economy in areas such as Aquaculture, Mining, Healthcare, Informaon Technology and Health Science Research, Post‐secondary Educaon, and Retail. -

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies

Community Files in the Centre for Newfoundland Studies A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | 0 | P | Q-R | S | T | U-V | W | X-Y-Z A Abraham's Cove Adams Cove, Conception Bay Adeytown, Trinity Bay Admiral's Beach Admiral's Cove see Port Kirwan Aguathuna Alexander Bay Allan’s Island Amherst Cove Anchor Point Anderson’s Cove Angel's Cove Antelope Tickle, Labrador Appleton Aquaforte Argentia Arnold's Cove Aspen, Random Island Aspen Cove, Notre Dame Bay Aspey Brook, Random Island Atlantic Provinces Avalon Peninsula Avalon Wilderness Reserve see Wilderness Areas - Avalon Wilderness Reserve Avondale B (top) Baccalieu see V.F. Wilderness Areas - Baccalieu Island Bacon Cove Badger Badger's Quay Baie Verte Baie Verte Peninsula Baine Harbour Bar Haven Barachois Brook Bareneed Barr'd Harbour, Northern Peninsula Barr'd Islands Barrow Harbour Bartlett's Harbour Barton, Trinity Bay Battle Harbour Bauline Bauline East (Southern Shore) Bay Bulls Bay d'Espoir Bay de Verde Bay de Verde Peninsula Bay du Nord see V.F. Wilderness Areas Bay L'Argent Bay of Exploits Bay of Islands Bay Roberts Bay St. George Bayside see Twillingate Baytona The Beaches Beachside Beau Bois Beaumont, Long Island Beaumont Hamel, France Beaver Cove, Gander Bay Beckford, St. Mary's Bay Beer Cove, Great Northern Peninsula Bell Island (to end of 1989) (1990-1995) (1996-1999) (2000-2009) (2010- ) Bellburn's Belle Isle Belleoram Bellevue Benoit's Cove Benoit’s Siding Benton Bett’s Cove, Notre Dame Bay Bide Arm Big Barasway (Cape Shore) Big Barasway (near Burgeo) see -

RESEARCH NOTE Beothuks and Methodists

RESEARCH NOTE Beothuks and Methodists THE EXTINCT BEOTHUK INDIANS of Newfoundland continue to intrigue and puzzle anthropologists and historians.1 Most discussions have included wonder ment that this population kept itself almost entirely aloof for several centuries from the European fishermen and settlers on the island, and maintained its defiant attitude to the end in the early 19th century. There seem to have been no peaceful exchanges of goods or friendly relations after the contacts in the early 17th and perhaps the 16th centuries. The evidence for whites living with the Beothuks, willingly or not, is dubious. There are no known cases of intermar riage or even of sexual relations between whites and Beothuks, and thus no métis or individuals of mixed race who might have functioned as go-betweens. Even the rare cases of adoption of orphaned Beothuk children led to no friendly inter course as far as we know. The reasons for this avoidance pattern by the Beothuks, as well as for their refusal to adopt firearms and European cod-fish ing technology or to engage in the fur trade, remain subjects of speculation. Whatever the explanations, the Beothuks chose to maintain their geographical and social distance from the Europeans. Their "strategy of withdrawal"2 was aberrant in terms of the usual pattern of contact and acculturation among New World aboriginal groups. It has been pointed out that there was no missionary influence, English or French, on the Beothuks, and that this is a unique situation in the Northeast. This has led a number of authors writing about the fate of the Beothuks to spec ulate on what might have happened had missionaries been able to reach them and convert them to Christianity.3 The examples of the Moravians in Labrador and the Jesuits in New France have been offered as illustrations of such success. -

Historical Methods in James P. Howley's the Beothucks

A Few Fabulous Fragments: Historical Methods in James P. Howley’s The Beothucks JEFF A. WEBB* Since it was published in 1915, James Howley’s The Beothucks has been an essential source for historians and novelists alike. Howley’s training as a geologist and surveyor shaped his scholarship. Rather than seeing his book as a history of the Beothuk, he saw it as preserving the memory of the Indigenous people of the island of Newfoundland. He deferred to philologists and ethnographers on issues of theory and most effectively marshalled his critical sense when evaluating the oral testimony he collected. This reading of the book revisits the foundational text and shows the lasting legacy of Howley’s scientific method and cultural assumptions upon the historiography and popular culture of the Beothuk. Depuis sa publication en 1915, The Beothuks de James Howley s’est révélé une source essentielle tant pour les historiens que pour les romanciers. La formation de Howley comme géologue et arpenteur transparaît dans son travail de recherche. Plutôt que de voir son livre comme une histoire des Béothuks, l’auteur l’a perçu comme un ouvrage préservant la mémoire des Autochtones de l’île de Terre-Neuve. Il s’en est remis aux philologues et aux ethnographes à propos des questions de théorie et a fait appel à son sens critique au moment d’évaluer les témoignages oraux recueillis par lui. La présente lecture de l’ouvrage permet de réexaminer ce texte fondateur et de présenter le legs durable de la méthode scientifique de Howley et de ses hypothèses culturelles sur l’historiographie et la culture populaire au sujet des Béothuks. -

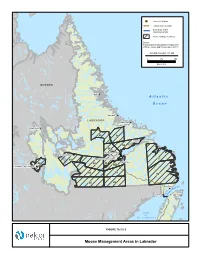

Moose Management Areas in Labrador !

"S Converter Station Transmission Corridor Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor Moose Management Area Source: Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation (2011) FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_550 0 75 150 Kilometres QUEBEC Nain ! A t l a n t i c O c e a n Hopedale ! LABRADOR Makkovik ! Postville ! Schefferville! 85 56 Rigolet ! 55 54 North West River ! ! Churchill Falls Sheshatshiu ! Happy Valley-Goose Bay 57 51 ! ! Mud Lake 48 52 53 53A Labrador City / Wabush ! "S 60 59 58 50 49 Red Bay Isle ! elle f B o it a tr Forteau ! S St. Anthony ! G u l f o f St. Lawrence ! Sept-Îles! Portland Creek! Cat Arm FIGURE 10.3.5-2 Twillingate! ! Moose Management Areas in Labrador ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Port Hope Simpson ! Mary's Harbour ! LABRADOR "S Converter Station Red Bay QUEBEC ! Transmission Corridor ± Submarine Cable Crossing Corridor Forteau ! 1 ! Large Game Management Areas St. Anthony 45 National Park 40 Source: Newfoundland and Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation (2011) 39 FIGURE ID: HVDC_ST_551 0 50 100 Kilometres 2 A t l a n t i c 3 O c e a n 14 4 G u l f 41 23 Deer Lake 15 22 o f ! 5 41 ! Gander St. Lawrence ! Grand Falls-Windsor ! 13 42 Corner Brook 7 24 16 21 6 12 27 29 43 17 Clarenville ! 47 28 8 20 11 18 25 29 26 34 9 ! St. John's 19 37 35 10 44 "S 30 Soldiers Pond 31 33 Channel-Port aux Basques ! ! Marystown 32 36 38 FIGURE 10.3.5-3 Moose and Black Bear Management Areas in Newfoundland Labrador‐Island Transmission Link Environmental Impact Statement Chapter 10 Existing Biophysical Environment Moose densities on the Island of Newfoundland are considerably higher than in Labrador, with densities ranging from a low of 0.11 moose/km2 in MMA 19 (1997 survey) to 6.82 moose/km2 in MMA 43 (1999) (Stantec 2010d). -

Micmac, Maliseet, Beothuk Collections Great Britain

Nova Scotia Curatorial Report Number 62 Nova Scotia Museum ~~,.. 1747 Summer Street ....-.~'- Halifax, Nova Scotia,Canada B3H 3A6 Department of Micmac, Education Maliseet, Nova Scotia Museum Complex Beothuk Collections 1n• Great Britain By R. H. Whitehead January 1988 \ f";.( ll~ ·.J r [ ( Curatorial Report Number 62 INVENTORY OF ( MICMAC, MALISEET AND BEOTHUK MATERIAL CULTURE IN INTERNATIONAL COLLECTIONS: GREAT BRITAIN ( ( r r r r r ( r Ruth Holmes Whitehead ( r [ r r NOVA SCO TIA MUSEUM Cu ra toria l Reports The Curatorial Reports of the Nova Scotia Museum con tain information on the collections and the preliminary r esults of research projects carried out under the program of the museum. The reports may be cited in publications but their manuscript status should clearly be indicated. r r r r TABLE OF CONTENTS r GREAT BRITAIN Bath: The American Museum in Great Britain 1 r Bristol: The City Museum and Art Gallery 2 Cambridge: The Scott Polar Research Institute 4 r Cambridge: The University Museum 6 East Cowes: Swiss Cottage Museum, Osborne House 12 r Edinburgh: The Royal Scottish Museum 17 Glasgow: The Hunterian Museum 28 Liverpool: Merseyside County Museum 29 r London: The Bethnal Green Museum 38 London: The Ethnography Department of the British Museum 39 London: The National Maritime Museum at Greenwich 65 r London: The Horniman Museum at Forest Hill 67 London: The Horniman Museum Library 68 London: The Science Museum 69 r 72 Northampton: The Leather Museum Northampton: The Central Museum 73 r Oxford: The Ashmolean Museum 74 Oxford: The Pitt Rivers Museum 77 r Saffron Walden: The Saffron Walden Museum 92 r Truro: The County Museum, Royal Institute of Cornwall 98 r\ r r r. -

Introduction Inuit

3.84 Opposing forces The juxtaposition of these two people speaks volumes. Sitting Bull (left) was a prominent Sioux Indian from the western U.S. representing Native American resistance to European encroachment. Sir Walter Raleigh (right) was a prominent 16th- 17th century figure who encouraged Elizabeth I to support voyages of exploration designed to exploit the wealth of the “new world.” TOPIC 3.6 Imagine you had to venture across an unknown region, as William Cormack did in 1822. How would you start your preparations? How might First Nations and Inuit have felt about European settlement in Newfoundland and Labrador? Introduction The lives of Aboriginal people in North and South longer allowed to do business there. To smooth the America underwent great change as more and transition for British and American merchants to more Europeans began to settle in their lands in take over the baleen trade, Governor Hugh Palliser the 1700s and 1800s. They faced social change, attempted to negotiate with Inuit* in 1765. Although new diseases, unfamiliar technologies, and (often) this did not eliminate all tensions between the cultures hostility. The experience of Aboriginal people in suddenly thrown together in business, it did contribute Newfoundland and Labrador was no different. to increased European activity and settlement along It was a time of great change for Inuit, Innu, Beothuk, the Labrador coast. Mi’kmaq, and Metis, as the European migratory fishery came to an end and was replaced by a resident fishery. The settlement of Moravians on the northern coast of Labrador in the later part of the eighteenth century led to consistent contact between Inuit and Europeans.