Arxiv:1805.07217V4 [Math.CO] 28 Jun 2021 Tilings of the Sphere By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tiling the Plane with Equilateral Convex Pentagons Maria Fischer1

Parabola Volume 52, Issue 3 (2016) Tiling the plane with equilateral convex pentagons Maria Fischer1 Mathematicians and non-mathematicians have been concerned with finding pentago- nal tilings for almost 100 years, yet tiling the plane with convex pentagons remains the only unsolved problem when it comes to monohedral polygonal tiling of the plane. One of the oldest and most well known pentagonal tilings is the Cairo tiling shown below. It can be found in the streets of Cairo, hence the name, and in many Islamic decorations. Figure 1: Cairo tiling There have been 15 types of such pentagons found so far, but it is not clear whether this is the complete list. We will look at the properties of these 15 types and then find a complete list of equilateral convex pentagons which tile the plane – a problem which has been solved by Hirschhorn in 1983. 1Maria Fischer completed her Master of Mathematics at UNSW Australia in 2016. 1 Archimedean/Semi-regular tessellation An Archimedean or semi-regular tessellation is a regular tessellation of the plane by two or more convex regular polygons such that the same polygons in the same order surround each polygon. All of these polygons have the same side length. There are eight such tessellations in the plane: # 1 # 2 # 3 # 4 # 5 # 6 # 7 # 8 Number 5 and number 7 involve triangles and squares, number 1 and number 8 in- volve triangles and hexagons, number 2 involves squares and octagons, number 3 tri- angles and dodecagons, number 4 involves triangles, squares and hexagons and num- ber 6 squares, hexagons and dodecagons. -

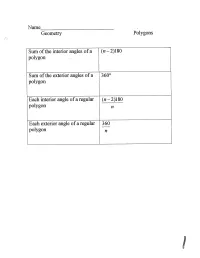

Geometry Polygons Sum of the Interior Angles of a (N

Name Geometry Polygons Sum of the interior angles of a (n - 2)180 polygon ~, Sum of the exterior angles of a 360° polygon Each interior angle of a regular (n - 2)180 i polygon n Each exterior angle of a regular 360 polygon n Geometry NAME: WORKSHEET: Polygon Angle Measures PERIOD: __ DATE: Use the given information to complete the table. Round to the nearest tenth if necessary. Measure of ONE Measure of ONE Interior Angle Exterior Angle # Sides INTERIOR Angle EXTERIOR Angle Sum Sum (Regular Polygon) (Regular Polygon) 1) 2) 14 3) 24 4) 17 5) 1080° 6) 900o 7) 5040° 8) 1620° 9) 150° lO) 120° 11) 156° 12) 10° 13) 7.2° 14) 90° 15) 0 Geometry NAME: WORKSHEET: Angles of Polygons - Review PERIOD: DATE: USING THE INTERIOR & EXTERIOR ANGLE SUM THEOREMS 1) The measure of one exterior angle of a regular polygon is given. Find the nmnbar of sides for each, a) 72° b) 40° 2) Find the measure of an interior and an exterior angle of a regular 46-gon. 3) The measure of an exterior angle of a regular polygon is 2x, and the measure of an interior angle is 4x. a) Use the relationship between interior and exterior angles to find x. b) Find the measure of one interior and exterior angle. c) Find the number of sides in the polygon and the type of polygon. 4) The measure of one interior angle of a regular polygon is 144°. How many sides does it have? 5) Five angles of a hexagon have measures 100°, 110°, 120°, 130°, and 140°. -

Lesson Plans 1.1

Lesson Plans 1.1 © 2009 Zometool, Inc. Zometool is a registered trademark of Zometool Inc. • 1-888-966-3386 • www.zometool.com US Patents RE 33,785; 6,840,699 B2. Based on the 31-zone system, discovered by Steve Baer, Zomeworks Corp., USA www zometool ® com Zome System Table of Contents Builds Genius! Zome System in the Classroom Subjects Addressed by Zome System . .5 Organization of Plans . 5 Graphics . .5 Standards and Assessment . .6 Preparing for Class . .6 Discovery Learning with Zome System . .7 Cooperative vs Individual Learning . .7 Working with Diverse Student Groups . .7 Additional Resources . .8 Caring for your Zome System Kit . .8 Basic Concept Plans Geometric Shapes . .9 Geometry Is All Around Us . .11 2-D Polygons . .13 Animal Form . .15 Attention!…Angles . .17 Squares and Rectangles . .19 Try the Triangles . .21 Similar Triangles . .23 The Equilateral Triangle . .25 2-D and 3-D Shapes . .27 Shape and Number . .29 What Is Reflection Symmetry? . .33 Multiple Reflection Symmetries . .35 Rotational Symmetry . .39 What is Perimeter? . .41 Perimeter Puzzles . .43 What Is Area? . .45 Volume For Beginners . .47 Beginning Bubbles . .49 Rhombi . .53 What Are Quadrilaterals? . .55 Trying Tessellations . .57 Tilings with Quadrilaterals . .59 Triangle Tiles - I . .61 Translational Symmetries in Tilings . .63 Spinners . .65 Printing with Zome System . .67 © 2002 by Zometool, Inc. All rights reserved. 1 Table of Contents Zome System Builds Genius! Printing Cubes and Pyramids . .69 Picasso and Math . .73 Speed Lines! . .75 Squashing Shapes . .77 Cubes - I . .79 Cubes - II . .83 Cubes - III . .87 Cubes - IV . .89 Even and Odd Numbers . .91 Intermediate Concept Plans Descriptive Writing . -

Equilateral Convex Pentagons Which Tile the Plane

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector JOURNAL OF COMBINATORIAL THEORY, Series A 39, l-18 (1985) Equilateral Convex Pentagons Which Tile the Plane M. D. HIRSCHHORN AND D. C. HUNT University qf New South Wales, Kensington, New South Wales, Australia 2033 Communicated by the Managing Editors Received April 23, 1983 It is shown that an equilateral convex pentagon tiles the plane if and only if it has two angles adding to 180” or it is the unique equilateral convex pentagon with angles A, B, C, D, E satisfying A + 2B = 360”. C + 2E = 360”, A + C+ 20 = 360” (A ~70.88”, BZ 144.56”, C=89.26”, D~99.93”, EZ 135.37”). (“ 1985 Academic Press, Inc Although the area of mathematical tilings has been of interest for a long time there is still much to be discovered. We do not even know which con- vex polygons tile the plane. Furthermore, for those polygons which do tile, new tilings are being found. It is known that all triangles and quadrilaterals tile the plane and those convex hexagons which do tile the plane have been classified. It is also known that no convex n-gon with n 2 7 tiles. In this paper we consider the problem of finding all equilateral convex pentagons which tile the plane. The upshot of our study is the following: THEOREM. An equilateral convex pentagon tiles the plane if and only if it has two angles adding to 180”, or it is the unique equilateral convex pentagon X with angles A, B, C, D, E satisfying A + 2B = 360”, C+ 2E = 360”, A + C+ 2D= 360” (Az70.88”, BE 144.56”, Cr89.26”, Dz99.93”, Ez 135.37”). -

The Geometry of the Space of Knotted Polygons

University of California Santa Barbara The Geometry of the Space of Knotted Polygons A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics by Kathleen S. Hake Committee in charge: Professor Kenneth Millett, Chair Professor Jason Cantarella Professor Daryl Cooper Professor Jon McCammond June 2018 The Dissertation of Kathleen S. Hake is approved. Professor Jason Cantarella Professor Daryl Cooper Professor Jon McCammond Professor Kenneth Millett, Committee Chair June 2018 The Geometry of the Space of Knotted Polygons Copyright c 2018 by Kathleen S. Hake iii To my inspiring and encouraging family. iv Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge my family for shaping me into the person that I am today. I am indebted to my parents and brothers for their constant love and support. My grandparents who pushed me to be my best and instilled in me a love for the outdoors. My great-grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins who pursued Ph.D.s in biology, chemistry, physics, philosophy, and more who have served as role models through out my life. I would like to acknowledge the people who have influenced me mathematically. I am incredibly appreciative of all the time spent with my advisor, Ken. In addition to the incredible mathematical support, he constantly provided optimism and encouragement, even from abroad. I would like to thank my committee and my mathematical siblings, Laura and Kyle, for their guidance. I am also grateful for my Loyola Marymount Uni- versity professors, Dr. Berg, Dr. Mellor, Dr. Crans, Dr. Shanahan, without whom I wouldn't have pursued graduate studies in mathematics. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,591,108 B2 Tuczek (45) Date of Patent: Sep

US007591.108B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,591,108 B2 Tuczek (45) Date of Patent: Sep. 22, 2009 (54) DOUBLE-CURVED SHELL OTHER PUBLICATIONS (75) Inventor: Florian Tuczek, Sebastian-Bach-Strasse Huybers, P. et al., “Polyhedral Sphere Subdivisions,” in Spatial Struc 36, Leipzig (DE) 04109 tures: Heritage, Present and Future, G.C. Giuliani, International (73) Assignee: Florian Tuczek, Leipzig (DE) Association for Shell and Spatial Structures International Sympo (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this sium, Mailand, 1955, p. 196, Fig. 13. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U.S.C. 154(b) by 26 days. (Continued) (21) Appl. No.: 11/766,219 Primary Examiner Richard E. Chilcot, Jr. Assistant Examiner Matthew J. Smith (22) Filed: Jun. 21, 2007 (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm Darby & Darby (65) Prior Publication Data US 2007/O251161 A1 Nov. 1, 2007 (57) ABSTRACT Related U.S. Application Data Triangulated shells can be free-formed but are uneconomical (63) Continuation of application No. PCT/EP2005/ compared to translational shells that can only be flat. Scale O12450, filed on Nov. 21, 2005. trans shells are limited in terms of number and arrangement of (30) Foreign Application Priority Data the openings. The present invention provides a free-formed, Dec. 21, 2004 (DE) ....................... 10 2004 O61485 custom-tailored shell Surface and a regularly shaped, mass produced shell surface that can be assembled fairly evenly (51) Int. Cl. from advantageously quadrangular mesh elements having E04B 700 (2006.01) coplanar node points. The flexibility of a triangle net of shell (52) U.S. -

Breaking News the 2019 IMO

Number 68 Spring 2019 La Force du Savoir (The Power of Knowledge) This 35 tonne granite sculpture was spotted at Sartilly, a French town near the Mont St Michel. It represents the range of books in a library and on the side shown you can see the Golden Ratio at the top. On the other side are seven words chosen by the children in the area: Liberte, Creation, Respect, Effort, Evolution, Imagination and Ecriture. Breaking News THE 2019 IMO This year the 60th International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO) will take place in Bath in July. The Opening Ceremony will take place on July 15 and the Closing Ceremony on July 21. The IMO is the World Championship Mathematics Competition for High School students and is held annually in a different country. The first IMO was held in Romania, with seven countries participating. It has gradually expanded to over 100 countries from five continents. The IMO Board ensures that the competition takes place each year and that each host country observes the regulations and traditions of the IMO. Last year the UK finished 12 out of 107 and Agnijo Banerjee was ranked 1st with a perfect score of six 7s. To find out more about the 2019 event, visit www.imo2019.uk/. Information about the IMO in general, with results over the years, visit www.imo-official.org/ EDITORIAL CROSSNUMBER Welcome to 2019. I hope this new year works out well 1 2 3 for you in whatever you do, wherever you are. On December 21st last year the largest known prime 4 number, 2182,589,933 − was discovered. -

Perimeter-Minimizing Tilings by Convex and Non-Convex Pentagons

Rose-Hulman Undergraduate Mathematics Journal Volume 16 Issue 1 Article 2 Perimeter-minimizing Tilings by Convex and Non-convex Pentagons Whan Ghang Massachusetts Institute of Technology Zane Martin Willams College Steven` Waruhiu University of Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rhumj Recommended Citation Ghang, Whan; Martin, Zane; and Waruhiu, Steven` (2015) "Perimeter-minimizing Tilings by Convex and Non-convex Pentagons," Rose-Hulman Undergraduate Mathematics Journal: Vol. 16 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholar.rose-hulman.edu/rhumj/vol16/iss1/2 ROSE- HULMAN UNDERGRADUATE MATHEMATICS JOURNAL PERIMETER-MINIMIZING TILINGS BY CONVEX AND NON-CONVEX PENTAGONS Whan Ghanga Zane Martinb Steven Waruhiuc VOLUME 16, NO. 1, SPRING 2015 Sponsored by Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology Department of Mathematics Terre Haute, IN 47803 aMassachusetts Institute of Technology Email: [email protected] bWilliams College c http://www.rose-hulman.edu/mathjournal University of Chicago ROSE-HULMAN UNDERGRADUATE MATHEMATICS JOURNAL VOLUME 16, NO. 1, SPRING 2015 PERIMETER-MINIMIZING TILINGS BY CONVEX AND NON-CONVEX PENTAGONS Whan Ghang Zane Martin Steven Waruhiu Abstract. We study the presumably unnecessary convexity hypothesis in the theorem of Chung et al. [CFS] on perimeter-minimizing planar tilings by convex pentagons. We prove that the theorem holds without the convexity hypothesis in certain special cases, and we offer direction for further research. Acknowledgements: This paper is work of the 2012 “SMALL” Geometry Group, an undergrad- uate research group at Williams College, continued in Martin’s thesis [M]. Thanks to our advi- sor Frank Morgan, for his patience, guidance, and invaluable input. Thanks to Professor William Lenhart for his excellent comments and suggestions. -

The Polygons of Albrecht Dürer -1525 G.H

The Polygons of Albrecht Dürer -1525 G.H. Hughes The early Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer published a book on geometry a few years before he died. This was intended to be a guide for young craftsmen and artists giving them both practical and mathematical tools for their trade. In the second part of that book, Durer gives compass and straight edge constructions for the „regular‟ polygons from the triangle to the 16-gon. We will examine each of these constructions using the original 1525 text and diagrams along with a translation. Then we will use Mathematica to carry out the constructions which are only approximate, in order to compare them with the regular case. In Appendix A, we discuss Dürer's approximate trisection method for angles, which is surprisingly accurate. Appendix B outlines what is known currently about compass and straightedge constructions and includes two elegant 19th century constructions. There is list of on-line resources at the end of this article which includes two related papers at DynamicsOfPolygons.org. The first of these papers is an analysis of the dynamics of the non-regular „Dürer polygons‟ under the outer billiards map (Tangent map). The second paper addresses the general issue of compass and straightedge constructions using Gauss‟s Disquisitiones Arithmeticae of 1801. Part I - Dürer’s life Albrecht Dürer was born in Nuremberg (Nürnberg) in 1471. Nuremberg lies on the Pegnitz River and is surrounded by the farmlands and woods of Bavaria. Medieval Germany was part of the Holy Roman Empire and when Frederick III died in 1493, his son Maximillian I became ruler of the Roman Empire and Germany. -

Time Travel and Other Mathematical Bewilderments Time Travel

TIME TRAVEL AND OTHER MATHEMATICAL BEWILDERMENTS TIME TRAVEL AND OTHER MATHEMATICAL BEWILDERMENTS MARTIN GARDNER me W. H. FREEMAN AND COMPANY NEW YORK Library of'Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Gardner, Martin, 1914- Time travel and other mathematical bewilderments. 1nclud~:s index. 1. Mathematical recreations. I. Title. QA95.G325 1987 793.7'4 87-11849 ISBN 0-7167-1924-X ISBN 0-7167-1925-8 @bk.) Copyright la1988 by W. H. Freeman and Company No part of this book may be reproduced by any mechanical, photographic, or electronic process, or in the form of a photographic recording, nor may it be stored in a retrieval system, transmitted, or otherwise copied for public or private use, without written permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 34567890 VB 654321089 To David A. Klarner for his many splendid contributions to recreational mathematics, for his friendship over the years, and in !gratitude for many other things. CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE Time Travel 1 CHAPTER TWO Hexes. and Stars 15 CHAPTER THREE Tangrams, Part 1 27 CHAPTER FOUR Tangrams, Part 2 39 CHAPTER FIVE Nontransitive Paradoxes 55 CHAPTER SIX Combinatorial Card Problems 71 CHAPTER SEVEN Melody-Making Machines 85 CHAPTER EIGHT Anamorphic. Art 97 CHAPTER NINE The Rubber Rope and Other Problems 11 1 viii CONTENTS CHAPTER TEN Six Sensational Discoveries 125 CHAPTER ELEVEN The Csaszar Polyhedron 139 CHAPTER TWELVE Dodgem and Other Simple Games 153 CHAPTER THIRTEEN Tiling with Convex Polygons 163 CHAPTER FOURTEEN Tiling with Polyominoes, Polyiamonds, and Polyhexes 177 CHAPTER FIFTEEN Curious Maps 189 CHAPTER SIXTEEN The Sixth Symbol and Other Problems 205 CHAPTER SEVENTEEN Magic Squares and Cubes 213 CHAPTER EIGHTEEN Block Packing 227 CHAPTER NINETEEN Induction and ~robabilit~ 24 1 CONTENTS ix CHAPTER TWENTY Catalan Numbers 253 CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE Fun with a Pocket Calculator 267 CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO Tree-Plant Problems 22 7 INDEX OF NAMES 291 Herewith the twelfth collection of my columns from Scientijic American. -

The Foundation of Euclid's Elements the 34 Definitions (Some of the Names of the Terms Have Been Changed from Heath’S Original Translation.) 1

Appendix C – Euclid’s Elements. The Foundation of Euclid's Elements The 34 Definitions (some of the names of the terms have been changed from Heath’s original translation.) 1. A point is that which has no part. 17. A diameter of the circle is any line drawn 2. A curve is breadthless length. through the center and terminated in both 3. The extremities of a curve are points. directions by the circumference of the circle, 4. A line is a curve which lies evenly with the and such a line also bisects the circle. points on themselves. 18. A semi-circle is the figure contained by the 5. A surface is that which has length and breadth diameter and the circumference cut-off by it. only. The center of the semi-circle is the same as that 6. The extremities of a surface are curves. of the circle. 7. A plane is a surface which lies evenly with the 19. Rectilineal figures are those which are lines on themselves. contained by lines. Triangles are those 8. A plane angle is the inclination to one another contained by three lines, quadrilaterals are of two curves in a plane which meet one another those contained by four lines, and multilaterals and do not lie in a straight line. are those contained by more than four lines. 9. When the sides of an angle are straight lines, 20. Of triangles, an equilateral triangle has three then the angle is called rectilineal. equal sides; an isosceles triangle has two of its sides alone equal; a scalene triangle has its 10. -

The Equilateral Pentagon at Zero Angular Momentum: Maximal Rotation Through Optimal Deformation

The Equilateral Pentagon at Zero Angular Momentum: Maximal Rotation Through Optimal Deformation William Tong and Holger R. Dullin School of Mathematics and Statistics University of Sydney, Australia July 4, 2018 Abstract A pentagon in the plane with fixed side-lengths has a two-dimensional shape space. Considering the pentagon as a mechanical system with point masses at the corners we answer the question of how much the pentagon can rotate with zero angular momen- tum. We show that the shape space of the equilateral pentagon has genus 4 and find a fundamental region by discrete symmetry reduction with respect to symmetry group D5. The amount of rotation ∆θ for a loop in shape space at zero angular momentum is interpreted as a geometric phase and is obtained as an integral of a function B over the region of shape space enclosed by the loop. With a simple variational argument we determine locally optimal loops as the zero contours of the function B. The resulting shape change is represented as a Fourier series, and the global maximum of ∆θ ≈ 45◦ is found for a loop around the regular pentagram. We also show that restricting allowed shapes to convex pentagons the optimal loop is the boundary of the convex region and gives ∆θ ≈ 19◦. 1 Introduction The possibility of achieving overall rotation at zero total angular momentum in an iso- lated mechanical system is surprising. It is possible for non-rigid bodies, in particular for systems of coupled rigid bodies, to change their orientations without an external torque using only internal forces, thus preserving the total angular momentum.