The Polygons of Albrecht Dürer -1525 G.H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digitalisation: Re-Imaging the Real Beyond Notions of the Original and the Copy in Contemporary Printmaking: an Exegesis

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2017 Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re- imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis Sarah Robinson Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Printmaking Commons Recommended Citation Robinson, S. (2017). Imperceptible Realities: An exhibition – and – Digitalisation: Re-imaging the real beyond notions of the original and the copy in contemporary printmaking: An exegesis. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1981 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). -

Extending Euclidean Constructions with Dynamic Geometry Software

Proceedings of the 20th Asian Technology Conference in Mathematics (Leshan, China, 2015) Extending Euclidean constructions with dynamic geometry software Alasdair McAndrew [email protected] College of Engineering and Science Victoria University PO Box 18821, Melbourne 8001 Australia Abstract In order to solve cubic equations by Euclidean means, the standard ruler and compass construction tools are insufficient, as was demonstrated by Pierre Wantzel in the 19th century. However, the ancient Greek mathematicians also used another construction method, the neusis, which was a straightedge with two marked points. We show in this article how a neusis construction can be implemented using dynamic geometry software, and give some examples of its use. 1 Introduction Standard Euclidean geometry, as codified by Euclid, permits of two constructions: drawing a straight line between two given points, and constructing a circle with center at one given point, and passing through another. It can be shown that the set of points constructible by these methods form the quadratic closure of the rationals: that is, the set of all points obtainable by any finite sequence of arithmetic operations and the taking of square roots. With the rise of Galois theory, and of field theory generally in the 19th century, it is now known that irreducible cubic equations cannot be solved by these Euclidean methods: so that the \doubling of the cube", and the \trisection of the angle" problems would need further constructions. Doubling the cube requires us to be able to solve the equation x3 − 2 = 0 and trisecting the angle, if it were possible, would enable us to trisect 60◦ (which is con- structible), to obtain 20◦. -

Es, and (3) Toprovide -Specific Suggestions for Teaching Such Topics

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 026 236 SE 004 576 Guidelines for Mathematics in the Secondary School South Carolina State Dept. of Education, Columbia. Pub Date 65 Note- I36p. EDRS Price MF-$0.7511C-$6.90 Deseriptors- Advanced Programs, Algebra, Analytic Geometry, Coucse Content, Curriculum,*Curriculum Guides, GeoMetry,Instruction,InstructionalMaterials," *Mathematics, *Number ConCepts,NumberSystems,- *Secondar.. School" Mathematies Identifiers-ISouth Carcilina- This guide containsan outline of topics to be included in individual subject areas in secondary school mathematics andsome specific. suggestions for teachin§ them.. Areas covered inclUde--(1) fundamentals of mathematicsincluded in seventh and eighth grades and general mathematicsin the high school, (2) algebra concepts for COurset one and two, (3) geometry, and (4) advancedmathematics. The guide was written With the following purposes jn mind--(1) to assist local .grOupsto have a basis on which to plan a rykathematics 'course of study,. (2) to give individual teachers an overview of a. particular course Or several cOur:-:es, and (3) toprovide -specific sUggestions for teaching such topics. (RP) Ilia alb 1 fa...4...w. M".7 ,noo d.1.1,64 III.1ai.s3X,i Ala k JS& # Aso sA1.6. It tilatt,41.,,,k a.. -----.-----:--.-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-:-.-. faidel1ae,4 icii MATHEMATICSIN THE SECONDARYSCHOOL Published by STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION JESSE T. ANDERSON,State Superintendent Columbia, S. C. 1965 Permission to Reprint Permission to reprint A Guide, Mathematics in Florida Second- ary Schools has been granted by the State Department of Edu- cation, Tallahassee, Flmida, Thomas D. Bailey, Superintendent. The South Carolina State Department of Education is in- debted to the Florida State DepartMent of Education and the aahors of A Guide, Mathematics in Florida Secondary Schools. -

Properties of N-Sided Regular Polygons

PROPERTIES OF N-SIDED REGULAR POLYGONS When students are first exposed to regular polygons in middle school, they learn their properties by looking at individual examples such as the equilateral triangles(n=3), squares(n=4), and hexagons(n=6). A generalization is usually not given, although it would be straight forward to do so with just a min imum of trigonometry and algebra. It also would help students by showing how one obtains generalization in mathematics. We show here how to carry out such a generalization for regular polynomials of side length s. Our starting point is the following schematic of an n sided polygon- We see from the figure that any regular n sided polygon can be constructed by looking at n isosceles triangles whose base angles are θ=(1-2/n)(π/2) since the vertex angle of the triangle is just ψ=2π/n, when expressed in radians. The area of the grey triangle in the above figure is- 2 2 ATr=sh/2=(s/2) tan(θ)=(s/2) tan[(1-2/n)(π/2)] so that the total area of any n sided regular convex polygon will be nATr, , with s again being the side-length. With this generalized form we can construct the following table for some of the better known regular polygons- Name Number of Base Angle, Non-Dimensional 2 sides, n θ=(π/2)(1-2/n) Area, 4nATr/s =tan(θ) Triangle 3 π/6=30º 1/sqrt(3) Square 4 π/4=45º 1 Pentagon 5 3π/10=54º sqrt(15+20φ) Hexagon 6 π/3=60º sqrt(3) Octagon 8 3π/8=67.5º 1+sqrt(2) Decagon 10 2π/5=72º 10sqrt(3+4φ) Dodecagon 12 5π/12=75º 144[2+sqrt(3)] Icosagon 20 9π/20=81º 20[2φ+sqrt(3+4φ)] Here φ=[1+sqrt(5)]/2=1.618033989… is the well known Golden Ratio. -

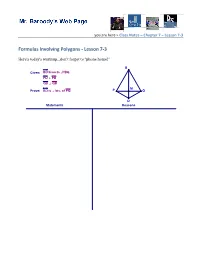

Formulas Involving Polygons - Lesson 7-3

you are here > Class Notes – Chapter 7 – Lesson 7-3 Formulas Involving Polygons - Lesson 7-3 Here’s today’s warmup…don’t forget to “phone home!” B Given: BD bisects ∠PBQ PD ⊥ PB QD ⊥ QB M Prove: BD is ⊥ bis. of PQ P Q D Statements Reasons Honors Geometry Notes Today, we started by learning how polygons are classified by their number of sides...you should already know a lot of these - just make sure to memorize the ones you don't know!! Sides Name 3 Triangle 4 Quadrilateral 5 Pentagon 6 Hexagon 7 Heptagon 8 Octagon 9 Nonagon 10 Decagon 11 Undecagon 12 Dodecagon 13 Tridecagon 14 Tetradecagon 15 Pentadecagon 16 Hexadecagon 17 Heptadecagon 18 Octadecagon 19 Enneadecagon 20 Icosagon n n-gon Baroody Page 2 of 6 Honors Geometry Notes Next, let’s look at the diagonals of polygons with different numbers of sides. By drawing as many diagonals as we could from one diagonal, you should be able to see a pattern...we can make n-2 triangles in a n-sided polygon. Given this information and the fact that the sum of the interior angles of a polygon is 180°, we can come up with a theorem that helps us to figure out the sum of the measures of the interior angles of any n-sided polygon! Baroody Page 3 of 6 Honors Geometry Notes Next, let’s look at exterior angles in a polygon. First, consider the exterior angles of a pentagon as shown below: Note that the sum of the exterior angles is 360°. -

Rembrandt, with a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings by Arthur Mayger Hind This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Rembrandt, With a Complete List of His Etchings Author: Arthur Mayger Hind Release Date: February 5, 2010 [Ebook 31183] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMBRANDT, WITH A COMPLETE LIST OF HIS ETCHINGS *** Rembrandt, With a Complete List of his Etchings Arthur M. Hind Fredk. A. Stokes Company 1912 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 Contents REMBRANDT . .1 BOOKS OF REFERENCE . .7 A CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF REMBRANDT'S ETCHINGS . .9 Illustrations 144, II. Rembrandt and his Wife, Saskia, 1636, B. 19 . vii 1, I. REMBRANDT'S MOTHER, Unfinished state. 1628: B. 354. 24 7, I. BEGGAR MAN AND BEGGAR WOMAN CON- VERSING. 1630. B. 164 . 24 20, I. CHRIST DISPUTING WITH THE DOCTORS: SMALL PLATE. 1630. B. 66 . 25 23, I. BALD-HEADED MAN (REMBRANDT'S FA- THER?) In profile r.; head only, bust added after- wards. 1630. B. 292. First state, the body being merely indicated in ink . 26 38, II. THE BLIND FIDDLER. 1631. B. 138 . 27 40. THE LITTLE POLANDER. 1631. B. 142. 139. THE QUACKSALVER. 1635. B. 129. 164. A PEASANT IN A HIGH CAP, STANDING LEANING ON A STICK. 1639. B. 133 . -

ANCIENT PROBLEMS VS. MODERN TECHNOLOGY 1. Geometric Constructions Some Problems, Such As the Search for a Construction That Woul

ANCIENT PROBLEMS VS. MODERN TECHNOLOGY SˇARKA´ GERGELITSOVA´ AND TOMA´ Sˇ HOLAN Abstract. Geometric constructions using a ruler and a compass have been known for more than two thousand years. It has also been known for a long time that some problems cannot be solved using the ruler-and-compass method (squaring the circle, angle trisection); on the other hand, there are other prob- lems that are yet to be solved. Nowadays, the focus of researchers’ interest is different: the search for new geometric constructions has shifted to the field of recreational mathematics. In this article, we present the solutions of several construction problems which were discovered with the help of a computer. The aim of this article is to point out that computer availability and perfor- mance have increased to such an extent that, today, anyone can solve problems that have remained unsolved for centuries. 1. Geometric constructions Some problems, such as the search for a construction that would divide a given angle into three equal parts, the construction of a square having an area equal to the area of the given circle or doubling the cube, troubled mathematicians already hundreds and thousands of years ago. Today, we not only know that these problems have never been solved, but we are even able to prove that such constructions cannot exist at all [8], [10]. On the other hand, there is, for example, the problem of finding the center of a given circle with a compass alone. This is a problem that was admired by Napoleon Bonaparte [11] and one of the problems that we are able to solve today (Mascheroni found the answer long ago [9]). -

Construction of Regular Polygons a Constructible Regular Polygon Is One That Can Be Constructed with Compass and (Unmarked) Straightedge

DynamicsOfPolygons.org Construction of regular polygons A constructible regular polygon is one that can be constructed with compass and (unmarked) straightedge. For example the construction on the right below consists of two circles of equal radii. The center of the second circle at B is chosen to lie anywhere on the first circle, so the triangle ABC is equilateral – and hence equiangular. Compass and straightedge constructions date back to Euclid of Alexandria who was born in about 300 B.C. The Greeks developed methods for constructing the regular triangle, square and pentagon, but these were the only „prime‟ regular polygons that they could construct. They also knew how to double the sides of a given polygon or combine two polygons together – as long as the sides were relatively prime, so a regular pentagon could be drawn together with a regular triangle to get a regular 15-gon. Therefore the polygons they could construct were of the form N = 2m3k5j where m is a nonnegative integer and j and k are either 0 or 1. The constructible regular polygons were 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 15, 16, 20, 24, 30, 32, 40, 48, ... but the only odd polygons in this list are 3,5 and 15. The triangle, pentagon and 15-gon are the only regular polygons with odd sides which the Greeks could construct. If n = p1p2 …pk where the pi are odd primes then n is constructible iff each pi is constructible, so a regular 21-gon can be constructed iff both the triangle and regular 7-gon can be constructed. -

( ) Methods for Construction of Odd Number Pointed

Daniel DOBRE METHODS FOR CONSTRUCTION OF ODD NUMBER POINTED POLYGONS Abstract: The purpose of this paper is to present methods for constructing of polygons with an odd number of sides, although some of them may not be built only with compass and straightedge. Odd pointed polygons are difficult to construct accurately, though there are relatively simple ways of making a good approximation which are accurate within the normal working tolerances of design practitioners. The paper illustrates rather complicated constructions to produce unconstructible polygons with an odd number of sides, constructions that are particularly helpful for engineers, architects and designers. All methods presented in this paper provide practice in geometric representations. Key words: regular polygon, pentagon, heptagon, nonagon, hendecagon, pentadecagon, heptadecagon. 1. INTRODUCTION n – number of sides; Ln – length of a side; For a specialist inured to engineering graphics, plane an – apothem (radius of inscribed circle); and solid geometries exert a special fascination. Relying R – radius of circumscribed circle. on theorems and relations between linear and angular sizes, geometry develops students' spatial imagination so 2. THREE - POINT GEOMETRY necessary for understanding other graphic discipline, descriptive geometry, underlying representations in The construction for three point geometry is shown engineering graphics. in fig. 1. Given a circle with center O, draw the diameter Construction of regular polygons with odd number of AD. From the point D as center and, with a radius in sides, just by straightedge and compass, has preoccupied compass equal to the radius of circle, describe an arc that many mathematicians who have found ingenious intersects the circle at points B and C. -

Tiling the Plane with Equilateral Convex Pentagons Maria Fischer1

Parabola Volume 52, Issue 3 (2016) Tiling the plane with equilateral convex pentagons Maria Fischer1 Mathematicians and non-mathematicians have been concerned with finding pentago- nal tilings for almost 100 years, yet tiling the plane with convex pentagons remains the only unsolved problem when it comes to monohedral polygonal tiling of the plane. One of the oldest and most well known pentagonal tilings is the Cairo tiling shown below. It can be found in the streets of Cairo, hence the name, and in many Islamic decorations. Figure 1: Cairo tiling There have been 15 types of such pentagons found so far, but it is not clear whether this is the complete list. We will look at the properties of these 15 types and then find a complete list of equilateral convex pentagons which tile the plane – a problem which has been solved by Hirschhorn in 1983. 1Maria Fischer completed her Master of Mathematics at UNSW Australia in 2016. 1 Archimedean/Semi-regular tessellation An Archimedean or semi-regular tessellation is a regular tessellation of the plane by two or more convex regular polygons such that the same polygons in the same order surround each polygon. All of these polygons have the same side length. There are eight such tessellations in the plane: # 1 # 2 # 3 # 4 # 5 # 6 # 7 # 8 Number 5 and number 7 involve triangles and squares, number 1 and number 8 in- volve triangles and hexagons, number 2 involves squares and octagons, number 3 tri- angles and dodecagons, number 4 involves triangles, squares and hexagons and num- ber 6 squares, hexagons and dodecagons. -

Rembrandt. the New Hollstein Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings

BR.OCT.pg.proof.corrs_Layout 1 16/09/2014 11:55 Page 675 massive undertaking and the broadest and brief sketch to a finished piece but more often Books most detailed survey of the artist’s prints to merely adjusted the shading or removed date, comprising seven volumes (two text, excess background lines. It is clear that some three of plates, and two with plates of copies). of the reworkings of his early plates were The authors of the New Hollstein took full carried out by others in the studio, among advantage of the array of technological them the Leiden printmaker Jan van Vliet, advances available to present-day scholars – known for having reproduced some of the relative facility of travel and the ability to Rembrandt’s paintings in print. Several produce high-quality digital images of prints anonymous printmakers appear to have also and X-radiographs of watermarks. They had a hand in reworking light sketches Rembrandt. The New Hollstein looked at works together and apart, sharing produced by the master around 1630 and Dutch & Flemish Etchings, Engravings large digital images that revealed changes dif- 1631. The authors were able to perceive these and Woodcuts 1450–1700. By Erik ficult if not impossible to identify with the underlying sketches thanks to enlarged digital Hinterding and Jaco Rutgers. 7 vols. 2,210 naked eye or a magnifying glass. details; such prints, extensively re-etched pp. incl. numerous col. + b. & w. ills. Their methods and findings are described in by another hand, are identified by a ‘w’ for (Sound and Vision Publishers, Ouderkerk the introduction to the first volume. -

Catalogue of the Eleventh Annual Exhibition of Engravings, Etchings, Woodcuts of the Xv and Xvi Centuries

CATALOGUE OF THE ELEVENTH ANNUAL EXHIBITION OF ENGRAVINGS, ETCHINGS, WOODCUTS OF THE XV AND XVI CENTURIES MARCH 3RD TO MARCH 2IST, 1936 M. KNOEDLER & COMPANY, INC. 14 EAST FIFTY-SEVENTH STREET NEW YORK ILLUSTRATED BOOKS AND NEWSPAPERS Discourse was deemed Man's noblest attribute, And written words the glory of his hand; Then followed Printing with enlarged command For thought — dominion vast and absolute For spreading truth, and making love expand. Now prose and verse sun\ into disrepute Must lacquey a dumb Art that best can suit The taste of this once-intellectual hand. A backward movement surely have we here, From manhood — bac\ to childhood; for the age — Bac\ towards caverned life's first rude career. U Avaunt this vile abuse of pictured page. Must eyes be all in all, the tongue and ear Nothing? Heaven keep us from a lower stage. WILLIAM WORDSWORTH ARTISTS REPRESENTED IN THIS EXHIBITION GERMANY ANONYMOUS (1425-1450) DOTTED PRINT 5 MASTER E. S 6 MARTIN SCHONGAUER 7 ANONYMOUS NORTH GERMAN (About 1480) 9 MASTER B. G 10 SCHOOL OF MARTIN SCHONGAUER 10 ISRAHEL VAN MECKENEM 10 MASTER M Z 13 AUGUSTIN HIRSCHVOGEL 14 HANS SEBALD LAUTENSACK 14 HANS BURGKMAIR 15 JOHANN ULRICH WECHTLIN (Pilgrim) 15 LUCAS CRANACH r6 NETHERLANDS MASTER F VB (F. van Brugge?) j$ LUCAS VAN LEYDEN Xo DIRICK JACOBSZOON VELLERT 21 ITALY NIELLO PRINT (Attributed to Francesco Francia) ....... 22 ANONYMOUS FLORENTINE: THE SIBYLS 22 CRISTOFANO ROBETTA 2, ANONYMOUS NORTH ITALIAN: "THE TAROCCHI CARDS" 24 DOMENICO BECCAFUMI (Master H-E) 2K ANONYMOUS XVI CENTURY: ROMAN SCHOOL 25 ANDREA MANTEGNA . _- -*5 SCHOOL OF ANDREA MANTEGNA 26 BARTOLOMEO DA BRESCIA 27 NICOLETTO ROSEX DA MODENA 28 JACOPO DE' BARBARI ...