Ultrasound of the Gastrointestinal Tract 749

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4L Eosinophilic Granuloma of Gastro-Intestinal Tract Caused by Herring Parasite Eustoma Rotundatum

BsrrmsH 2 May 1964 MEDICAL JOURNAL 1141 4L Eosinophilic Granuloma of Gastro-intestinal Tract Caused by Herring Parasite Eustoma rotundatum B. STERRY ASHBY,* M.B., F.R.C.S.; P. J. APPLETONt M.B., B.S. IAN DAWSON,4 M.D., M.R.C.P. Brit. med.JY., 1964, 1, 1141-1145 For over 25 years sporadic reports have been appearing in the came from many countries in many different parts of the world. literature of cases of eosinophilic granuloma arising in various The essential details of these cases are recorded in Table I parts of the gastro-intestinal tract. Kaiiser (1937) described and Fig. 1. the first cases. In a search of the literature, which although The one feature common to all these case reports is the extensive is not claimed to be exhaustive, 47 papers were microscopical appearance of the lesion. No matter which part found, describing a total of 89 cases. They occurred through- of the alimentary tract is involved, the histological description out the alimentary tract from pharynx to rectum, though the is the same-an oedematous connective-tissue stroma with an majority were in the stomach and small intestine, and they increase of capillaries and lymphatics, and showing a massive diffuse eosinophil-cell infiltration, usually confined to the sub- * Surgical Registrar, Westminster Hospital and Medical School London. the muscularis mucosae and t House-Surgeon, Westminster Hospital and Medical School, Iondon. mucosa but sometimes splitting t Reader in Pathology, Westminster Hospital and Medical School, spreading into the muscle layer. The mucosa is almost always London. intact. -

Studies of the Function of the Human Pylorus : and Its Role in The

+.1 Studúes OlTlæ Ftrnctíon OJTIrc Humanfolonts And,Iß R.ole InTlæ Riegulø;tíon OÍ Cústríß Drnptging David R. Fone Departments of Medicine and Gastroenterology, Royal Adelaide Hospital University of Adelaide August 1990 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS . SUMMARY vil DECLARATION...... X DED|CAT|ON.. .. ... xt ACKNOWLEDGMENTS xil CHAPTER 1 ANATOMY OF THE PYLORUS 1.1 INTRODUCTION.. 1 1.2 MUSCULAR ANATOMY 2 1.3 MUCOSAL ANATOMY 4 1.4 NEURALANATOMY 1.4.1 Extrinsic lnnervation of the Pylorus 5 1.4.2 lntrinsic lnnervation of the Pylorus 7 1.5 INTERSTITIAL CELLS OF CAJAL 8 1.6 CONCLUSTON 9 CHAPTER 2 MEASUREMENT OF PYLORIC MOTILITY 2.1 INTRODUCTION 10 2.2 METHODOLOG ICAL CHALLENGES 2.2.1 The Anatomical Mobility of the Pylorus . 10 2.2.2 The Narrowness of the Zone of Pyloric Contraction 12 2.3 METHODS USED TO MEASURE PYLORIC MOTILITY 2.3.1 lntraluminal Techniques 2.3.1.1 Balloon Measurements. 12 t 2.3 1.2 lntraluminal Side-hole Manometry . 13 2.3 1.9 The Sleeve Sensor 14 2.3 1.4 Endoscopy. 16 2.3 1.5 Measurements of Transpyloric Flow . 16 2.3 'I .6 lmpedance Electrodes 16 2.3.2 Extraluminal Techniques For Recording Pyl;'; l'¡"r¡iit¡l 2.3.2.'t Strain Gauges . 17 2.3.2.2 lnduction Coils . 17 2.3.2.3 Electromyography 17 2.3.3 Non-lnvasive Approaches For Recording 2.3.3.1 Radiology :ï:: Y:1":'1 18 2.3.9.2 Ultrasonography . 1B 2.3.3.3 Electrogastrography 19 2.3.4 ln Vitro Studies of Pyloric Muscle 19 2.4 CONCLUSTON. -

GI Motility-I (Deglutition and Motor Functions of Stomach)

Lecture series Gastrointestinal tract Professor Shraddha Singh, Department of Physiology, KGMU, Lucknow GASTROINTESTINAL MOTILITY-1 (Deglutation and motor function of stomach) Mastication (Chewing) - the anterior teeth (incisors) providing a strong cutting action and the posterior teeth (molars), a grinding action – canine tearing - All the jaw muscles working together can close the teeth with a force as great as 25 Kg on the incisors and 90 Kg on the molars. - Most of the muscles of chewing are innervated by the motor branch of the 5th cranial nerve, and the chewing process is controlled by nuclei in the brain stem. - Stimulation of areas in the hypothalamus, amygdala, and even the cerebral cortex near the sensory areas for taste and smell can often cause chewing Chewing Reflex - The presence of a bolus of food in the mouth at first initiates reflex inhibition of the muscles of mastication, which allows the lower jaw to drop. ↓ - The drop in turn initiates a stretch reflex of the jaw muscles that leads to rebound contraction ↓ - raises the jaw to cause closure of the teeth ↓ - compresses the bolus again against the linings of the mouth, which inhibits the jaw muscles once again Chewing Reflex - most fruits and raw vegetables because these have indigestible cellulose membranes around their nutrient portions that must be broken before the food can be digested - Digestive enzymes act only on the surfaces of food particles - grinding the food to a very fine particulate consistency prevents excoriation of the GIT (Stomach) Swallowing (Deglutition) -

The Arrest of Intestinal Epithelial ' Turnover' by the Use of X-Irradiation

Gut, 1962, 3, 26 Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.3.1.26 on 1 March 1962. Downloaded from The arrest of intestinal epithelial ' turnover' by the use of x-irradiation G. WIERNIK, R. G. SHORTER, AND B. CREAMER From St. Thomas's Hospital and Medical School, London sYNoPsIs Mitotic activity and hence cell turnover has been abolished by x-irradiation with 1,000 r. in segments of the rat's gut. The whole stomach, the ascending colon, and 5 cm. of jejunum and ileum were irradiated and the changes observed histologically up to three days. Cessation of cell turnover in the small intestine is followed by cell death and desquamation within 24 hours, leading to denudation of the epithelium and collapse of villous structure. The pylorus and colon showed similar but less marked changes. In contrast the fundus and body of the stomach were unaffected by the absence of mitosis over a period of three days. It is concluded that cell turnover is, in part, necessary to maintain the mucosal structure, particularly the villous pattern in the small intestine. The gastro-intestinal epithelium is a dynamic METHODS structure. Although it appears an intact and lush Wistar rats of either sex weighing 200 g. were used. The membrane to histological examination, it is being animals were anaesthetized with intraperitoneal pento- continuously replaced and desquamated extremely barbitone sodium B.P. The segment of gut to be irradiated quickly. This replacement ofcells results from intense was delivered through an abdominal incision and its http://gut.bmj.com/ division in the crypts, the cells so formed migrating extent marked by fine silk loops. -

The Gallbladder

The Gallbladder Anatomy of the gallbladder Location: Right cranial abdominal quadrant. In the gallbladder fossa of the liver. o Between the quadrate and right medial liver lobes. Macroscopic: Pear-shaped organ Fundus, body and neck. o Neck attaches, via a short cystic duct, to the common bile duct. Opens into the duodenum via sphincter of Oddi at the major duodenal papilla. Found on the mesenteric margin of orad duodenum. o 3-6 cm aboral to pylorus. 1-2cm of distal common bile duct runs intramural. Species differences: Dogs: o Common bile duct enters at major duodenal papilla. Adjacent to pancreatic duct (no confluence prior to entrance). o Accessory pancreatic duct enters at minor duodenal papilla. ± 2 cm aboral to major duodenal papilla. MAJOR conduit for pancreatic secretions. Cats: o Common bile duct and pancreatic duct converge before opening at major duodenal papilla. Thus, any surgical procedure that affects the major duodenal papilla can affect the exocrine pancreatic secretions in cats. o Accessory pancreatic duct only seen in 20% of cats. 1 Gallbladder wall: 5 histologically distinct layers. From innermost these include: o Epithelium, o Submucosa (consisting of the lamina propria and tunica submucosa), o Tunica muscularis externa, o Tunica serosa (outermost layer covers gallbladder facing away from the liver), o Tunica adventitia (outermost layer covers gallbladder facing towards the liver). Blood supply: Solely by the cystic artery (derived from the left branch of the hepatic artery). o Susceptible to ischaemic necrosis should its vascular supply become compromised. Function: Storage reservoir for bile o Concentrated (up to 10-fold), acidified (through epithelial acid secretions) and modified (by the addition of mucin and immunoglobulins) before being released into the gastrointestinal tract at the major duodenal. -

Effect of Chronic Ethanol Ingestion on Enterocyte Turnover in Rat Small Intestine

Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.28.1.52 on 1 January 1987. Downloaded from Gut, 1987, 28, 52-55 Effect of chronic ethanol ingestion on enterocyte turnover in rat small intestine R MAZZANTI AND W J JENKINS From the Department of' Medicine, Royal Free Hospital School of Medicine, Rowland Hill Street, Londlon SUMMARY Whether chronic ethanol ingestion significantly damages the small intestine remains controversial. To clarify this we have analysed the morphology of the small intestinal epithelium and quantified its renewal in chronically ethanol fed rats. Twenty adult male rats were pair fed for 28 days a nutritionally adequate liquid diet containing either ethanol as 36% of total calories or an isocaloric diet in which fat substituted for ethanol. Crypt cell production rate was determined in the jejunum and ileum by the metaphase arrest method. Weight gain and small intestinal morphology were similar in ethanol fed and control rats, but enterocyte turnover was significantly reduced in the jejunum (p<O.05) and ileum (p<0.0l) of the ethanol fed rats. This effect of ethanol on the small intestine is probably systemic rather than local, because the changes in jejunum and ileum were similar, and it may contribute to the development of malnutrition in chronic alcoholics. A variety of changes in intestinal function have Methods been reported after acute or habitual alcohol consumption.' Impaired absorption of vitamins,25 ANIMALS sugars6 7 and amino acids8 9 has been shown in Twenty adult male Sprague-Dawley rats, which http://gut.bmj.com/ the presence of ethanol, and the chronic consump- initially weighed between 210 g and 310 g, were tion of ethanol is often associated with malnutrition maintained in single cages on a 12 hour light-dark and diarrhoea, but whether these are caused by cycle at 21 ±1°C room temperature. -

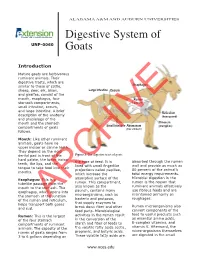

Digestive System of Goats 3 References

ALABAMA A&M AND AUBURN UNIVERSITIES Digestive System of UNP-0060 Goats Introduction Mature goats are herbivorous ruminant animals. Their digestive tracts, which are similar to those of cattle, Esophagus sheep, deer, elk, bison, Large Intestine Cecum and giraffes, consist of the mouth, esophagus, four Rumen stomach compartments, (paunch) small intestine, cecum, and large intestine. A brief Reticulum description of the anatomy (honeycomb) and physiology of the mouth and the stomach Omasum Small Intestine Abomasum (manyplies) compartments of goats (true stomach) follows. Mouth: Like other ruminant animals, goats have no upper incisor or canine teeth. They depend on the rigid dental pad in front of the Figure 1. The digestive tract of goats. hard palate, the lower incisor the type of feed. It is absorbed through the rumen teeth, the lips, and the lined with small fingerlike wall and provide as much as tongue to take food into their projections called papillae, 80 percent of the animal’s mouths. which increase the total energy requirements. Microbial digestion in the Esophagus: This is a absorptive surface of the rumen is the reason that tubelike passage from the rumen. This compartment, ruminant animals effectively mouth to the stomach. The also known as the use fibrous feeds and are esophagus, which opens into paunch, contains many maintained primarily on the stomach at the junction microorganisms, such as roughages. of the rumen and reticulum, bacteria and protozoa, helps transport bothARCHIVE gases that supply enzymes to Rumen microorganisms also and cud. break down fiber and other feed parts. Microbiological convert components of the feed to useful products such Rumen: This is the largest activities in the rumen result as essential amino acids, of the four stomach in the conversion of the B-complex vitamins, and compartments of ruminant starch and fiber of feeds to vitamin K. -

Normal Gastrointestinal Motility and Function Esophagus

Normal Gastrointestinal Motility and Function "Motility" is an unfamiliar word to many people; it is used primarily to describe the contraction of the muscles in the gastrointestinal tract. Because the gastrointestinal tract is a circular tube, when these muscles contract, they close off the tube or make the opening inside smaller - they squeeze. These muscles can contract in a synchronized way to move the food in one direction (usually downstream, but occasionally upstream for short distances); this is called peristalsis. If you looked at the intestine, you would see a ring of contraction that moves along pushing contents ahead of it. At other times, the muscles in adjacent parts of the gastrointestinal tract squeeze more or less independently of each other: this has the effect of mixing the contents but not moving them up or down. Both kinds of contraction patterns are called motility. The gastrointestinal tract is divided into four distinct parts: the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine (colon). They are separated from each other by special muscles called sphincters which normally stay tightly closed and which regulate the movement of food and food residues from one part to another. Each part of the gastrointestinal tract has a unique function to perform in digestion, and as a result each part has a distinct type of motility and sensation. When motility or sensations are not appropriate for performing this function, they cause symptoms such as bloating, vomiting, constipation, or diarrhea which are associated with subjective sensations such as pain, bloating, fullness, and urgency to have a bowel movement. -

Effects of Microflora on the Dimensions of Enterocyte Microvilli in the Rat J.-C

Effects of microflora on the dimensions of enterocyte microvilli in the rat J.-C. Meslin, E. Sacquet, S. Delpal To cite this version: J.-C. Meslin, E. Sacquet, S. Delpal. Effects of microflora on the dimensions of enterocyte microvilli in the rat. Reproduction Nutrition Développement, 1984, 24 (3), pp.307-314. hal-00898154 HAL Id: hal-00898154 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00898154 Submitted on 1 Jan 1984 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Effects of microflora on the dimensions of enterocyte microvilli in the rat J.-C. MESLIN, E. SACQUET S. DELPAL Station de Recherches de Nutrition, /./V./7./! 78350 Jouy-en-Josas, France. (*) Laboratoire des Animaux sans Germes, CNRS, lNRA, 78350 Jouy-en-Josas, France. Summary. The length and diameter of enterocyte microvilli at mid-villus position were measured on electron-micrographs. The duodenum, jejunum and ileum of axenic (germfree) and holoxenic (conventional) inbred rats fed the same diet have been studied. The microvilli were significantly shorter in all these intestinal regions when the microflora was present. The decrease in microvillus length (due to the presence of microflora), expressed as a percentage of the length in axenic rat, was 5 % in the duodenum, 9 % in the jejunum and 18 % in the ileum. -

Distance Between Major and Minor Duodenal Papilla from Pylorus – a Cadaveric Study M

International Journal of Anatomy and Research, Int J Anat Res 2018, Vol 6(2.2):5239-45. ISSN 2321-4287 Original Research Article DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.16965/ijar.2018.167 DISTANCE BETWEEN MAJOR AND MINOR DUODENAL PAPILLA FROM PYLORUS – A CADAVERIC STUDY M. Pairoja Sultana *1, C.K. Lakshmidevi 2. *1Assistant professor in Anatomy, ACSR Govt. medical college, Nellore, Andhra Pradesh, India. 2 Professor and Head of the department of Anatomy, ACSR Govt. medical college, Nellore, Andhra Pradesh, India. ABSTRACT Introduction: Without the knowledge of the normal pattern of the duct system and its variations, a radiologist can’t interpret an Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) picture. So it becomes important to study the anatomy of pancreatic ducts, their relation to each other, to common bile duct and to duodenum in the available human cadavers. The present paper is about the study of distance between minor and major duodenal papilla from pylorus which was carried out on 96 cadaveric specimens of human duodeno-pancreas. To visualise and to see distance between minor and major duodenal papillae is necessary for the endoscopist who aims to perform the dilation, stenting, or papillotomy of the minor papilla. Materials and Methods: The study was conducted in 96 (64 male and 32 female) cadavers. Major and minor duodenal papillae were visualized through eosin dye installation in both common bile duct and the accessory pancreatic duct. The measurement of distance between the duodenal papillae and to pylorus was done in cm. Results: In the present work, the mean ± SD of the Distance between pylorus to MAP is 8.05 ± 1.71 cm, pylorus to MIP is 6.19 ± 1.49 cm, the major to minor duodenal papilla was on an average 2.02 ± 0.40 cm, these distances were more in males as compared to females. -

Cell-Specific Gene Expression: Pylorus Morphogenesis and Hedgehog-Regulated Enhancers

CELL-SPECIFIC GENE EXPRESSION: PYLORUS MORPHOGENESIS AND HEDGEHOG-REGULATED ENHANCERS by Aaron Mark Udager A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Cell and Developmental Biology) in the University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Deborah L. Gumucio, Chair Professor Gregory R. Dressler Professor Ronald J. Koenig Professor Linda C. Samuelson Associate Professor Deneen M. Wellik Assistant Professor Scott E. Barolo © Aaron Mark Udager 2010 To my wife Kara and my parents Mark and Anita ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I’d like to thank my mentor Deb Gumucio. Over the past four years, you have given me freedom to explore and opportunities to succeed (as well as fail). Without a doubt, these experiences have made me a better scientist. I’ll always admire your love of science and the dedication you show to teaching students, supporting your employees, and maintaining a family. I know we’ll remain good friends in the future. Second, I’d like to thank the members of my thesis committee. You challenged me when I needed to be and provided critical feedback at several key junctures in this project. Our meetings over the past several years have been an important part of my growth as a scientist. Third, I need to thank the extensive contributions made to this project by our collaborators, both here at the University and abroad. I’d like to thank Drs. Doug Engel and Kim-Chew Lim in this department for providing Gata3lacZ/+ mice and sharing a number of other resources. I’d also like to thank Dr. -

Narrow Band Imaging Helps Identify the Ectopic Opening of the Common Bile Duct During Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography

Turk J Gastroenterol 2017; 28: 69-70 Narrow band imaging helps identify the ectopic opening of the common bile duct during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography To the Editor, The ectopic opening of the common bile duct (CBD) into the stomach and pyloric canal is extremely rare, and it accounts for a mere 0.43% of patients undergo- ing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) (1); however, when present, it often makes it dif- ficult to recognize the papilla during endoscopy. Here we present a case where narrow band imaging (NBI) was used to discover an ectopic opening of the CBD. A 56-year-old male who underwent cholecystectomy 6 months prior was referred to our hospital because of a two-week history of abdominal pain, nausea, jaundice, and pruritus. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancrea- tography (MRCP) showed a hook-shaped CBD and a Figure 1. Abdominal MRCP showed a hook-shaped CBD with a stone single stone (Figure 1). Written informed consent was MRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; CBD: common bile duct obtained from the patient before ERCP. The major and minor papilla were not found from the slack pylorus to the pars horizontalis duodeni by a duodenoscope and then a gastroscope. The gastroscope was pulled back to the gastric antrum, where a small amount of bile ap- peared to adhere to the anterior wall. We switched to NBI for performing an examination, which depicts bile as red and blood as black. A bright red fluid was seen discharging from a slit, 3 mm in length, at the 9 o’clock position on the left side of the pylorus (Figure 2).