Dance Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cavafy Song Bibliography Version2 1-15-20

C. P. Cavafy Music Resource Guide: Song and Music Settings of Cavafy’s Poetry Researched by Vassilis Lambropoulos Compiled by Peter Vorissis, Haris Missler, and Artemis Leontis* Modern Greek Program & C. P. Cavafy Professorship in Modern Greek Departments of Classical Studies and Comparative Literature University of Michigan Version 2: January 14, 2020 Please send additions and corrections to [email protected] * with gratitude to Dimitris Gousopoulos for major additions of the melopoiesis of Cavafy’s poetry in rock, pop, hip hop, metal, indie, and punk Cavafy Music Resource Guide 1 Cavafy Song Settings: A Music Resource Guide Adamopoulos, Loukas (Αδαμόπουλος, Λουκάς). 1981. «Επέστρεφε» (Come back). Κέρκυρα ’81: Αγώνες ελληνικού τραγουδιού—Τα 30 τραγούδια (Kerkyra ’81: Greek song contest). Αthens: Minos. Setting: «Επέστρεφε» (Come Back). Anabalon, Patricio. 2003. Itaca. Poetas griegas musicalizados. Santiago: Alerce Producciones Fonograficas S.A. Includes the songs “Itaca” (Ithaka), “Regresa” (Come back), “Una Noche/Las Ventanas” (One night / Windows). Anagnostatos, Yiannis (Αναγνωστάτος Γιάννης, also known as Lolek). 2010. «Κεριά». In the compilation Ποιήματα του Κ.Π. Καβάφη (Poems of C.P. Cavafy). Athens: Odos Panos 147 (January–March). (See “Lolek” below). Anestopoulos, Thanos (Ανεστόπουλος, Θάνος). 2001. «Κεριά» (Candles). In Οι ποιητές γυμνοί τραγουδάνε (Poets sing naked). Athens and Patra: Κονσερβοκούτι. For voice and electronic accompaniment or guitar. Composed and sung by Thanos Anestopoulos (Θάνος Ανεστόπουλος) under the pseudonym ΑΣΘΟΝ ΣΑΠΤΟΥΣ ΛΕΟΝΟΣ, an anagram of his name. First released as a cassette by the magazine «Κονσερβοκούτι» (Tin can, the magazine of OEN, Οργάνωση Επαναστατικής Νεολαίας, Organization of Revolutionary Youth). Setting: «Κεριά» (Candles). Angelakis, Manolis (Αγγελάκης, Μανώλης) & τα Θηρία (and the Beasts). -

View PDF Document

Society of Composers Inc. National Student Conference 2001 Presented by The Indiana School of Music welcomes you to the 2001 Society of Composers Inc. National Student Conference Dear Composers and Friends: I am pleased to attend the Third Annual National Student Conference of the Society of Composers, Inc. This event, ably hosted by Jason Bahr with generous support from Don Freund, will give you that rare opportunity to meet and hear each other's works performed by some of the most talented performers in this country. Take advantage of this timethese are your future colleagues, for you can never predict when you will meet them again. This is the weekend we will choose the three winners of the SCI/ASCAP Student Composition Commission Competition, to be announced at the banquet on Saturday evening. You will hear three new compositions by the winners of the 2000 competition: Lansing D. McLoskey's new choral work on Saturday at 4:00 p.m.; Karim Al-Zand's Wind Ensemble work to be performed Thursday night at 8:00 p.m.; and Ching-chu Hu's chamber ensemble work on the Friday night concert. SCI is grateful to Fran Richard and ASCAP for their support with this ongoing commissioning project. Last month I was asked by the editor of the on-line journal at the American Music Center in New York to discuss the dominant musical style of today and to predict what the dominant musical style might be of tomorrow. If only I could predict future trends! And yet, today's music depends upon whom you ask. -

Passacaglia PRINT

On Shifting Grounds: Meandering, Modulating, and Möbius Passacaglias David Feurzeig Passacaglias challenge a prevailing assumption underlying traditional tonal analysis: that tonal motion proceeds along a unidirectional “arrow of time.” The term “continuous variation,” which describes characteristic passacaglia technique in contrast to sectional “Theme and Variations” movements, suggests as much: the musical impetus continues forward even as the underlying progression circles back to its starting point. A passacaglia describes a kind of loop. 1 But the loop of a traditional passacaglia is a rather flattened one, ovoid rather than circular. For most of the pattern, the tonal motion proceeds in one direction—from tonic to dominant—then quickly drops back to the tonic, like a skier going gradually up and rapidly down a slope. The looping may be smoother in tonic-requiring passacaglia themes (those which end on the dominant) than in tonic- providing themes, as the dominant harmony propels the music across the “seam” between successive statements of the harmonic pattern. But in both types, a clear dominant-tonic cadence tends to work against a sense of seamless circularity. This is not the case for some more recent passacaglias. A modern compositional type, which to my knowledge has not been discussed before as such, is the modulatory passacaglia.2 Modulating passacaglia themes subvert tonal closure via progressions which employ elements of traditional tonality but veer away from the putative tonal center. Passacaglias built on these themes may take on a more truly circular form, with no obvious start or endpoint. This structural ambiguity is foreshadowed in some Baroque ground-bass compositions. -

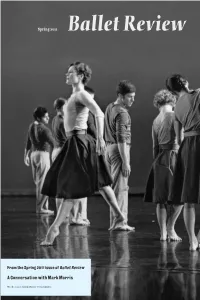

A Conversation with Mark Morris

Spring2011 Ballet Review From the Spring 2011 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Mark Morris On the cover: Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. 4 Paris – Peter Sparling 6 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 8 Stupgart – Gary Smith 10 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 13 Paris – Peter Sparling 15 Sarasota, FL – Joseph Houseal 17 Paris – Peter Sparling 19 Toronto – Gary Smith 20 Paris – Leigh Witchel 40 Joel Lobenthal 24 A Conversation with Cynthia Gregory Joseph Houseal 40 Lady Aoi in New York Elizabeth Souritz 48 Balanchine in Russia 61 Daniel Gesmer Ballet Review 39.1 56 A Conversation with Spring 2011 Bruce Sansom Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Sandra Genter 61 Next Wave 2010 Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman Michael Porter Senior Editor: Don Daniels 68 Swan Lake II Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Darrell Wilkins 48 70 Cherkaoui and Waltz Associate Editor: Larry Kaplan Joseph Houseal Copy Editor: 76 A Conversation with Barbara Palfy Mark Morris Photographers: Tom Brazil Costas 87 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Associates: Peter Anastos 100 Check It Out Robert Greskovic George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall 70 Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Supon David Vaughan Edward Willinger Sarah C. Woodcock CoverphotobyTomBrazil: MarkMorris’FestivalDance. Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. (Photos: Tom Brazil) 76 ballet review A Conversation with – Plato and Satie – was a very white piece. Morris: I’m postracial. Mark Morris BR: I like white. I’m not against white. Morris:Famouslyornotfamously,Satiesaid that he wanted that piece of music to be as Joseph Houseal “white as classical antiquity,”not knowing, of course, that the Parthenon was painted or- BR: My first question is . -

Music in the “New World”: from New Spain to New England Objectives

Music in the “New World”: From New Spain to New England objectives I. the villancico in Peru (what’s new about it) II. Spanish opera in Peru III. music in the British colonies [focus on the terms and the two works on your listening list] The “Age of Discovery” (for Europeans) • 1492: Christopher Columbus (Spain) • 1494: Treaty of Tordesillas • 1500: “discovery” of Brazil by Portuguese 1 Pre‐Columbian Civilizations • Mayans (Guatemala, 4th‐8th c.) • Aztecs (Mexico, late 12th c.‐1521) • Incas (Peru, 13th c.‐1533) music of Pre‐Columbian Civilizations • NO music survives • Music Sources: – 1. surviving instruments – 2. iconography – 3. writings about music by missionaries • music was inseparable from religious ritual 1. Surviving Instruments Aztec Flutes Incan stone panpipe 2 2. Iconography “New World” 17th‐18th c. Sacred Music in Hispanic America • Catholic liturgical music – tool for evangelism • Masses, Motets, etc. (in Latin) – Prima prattica works influenced by “Golden Age of Spanish Polyphony” • Cristóbal Morales • Tomás Luis de Victoria 3 Sacred Music in New Spain (Mexico) • Villancico – strophic song in Spanish with refrain Estribillo (refrain) Copla (strophe) A b b a or A Juan del Encina: Oy comamos y bebamos, villancico (late 15th cent.) • Estrebillo: • Refrain: Oy comamos y bebamos Today let’s eat and drink y cantemos y holguemos, and sing and have a good time que mañana ayunaremos. for tomorrow we will fast. • Copla 1 • Stanza 1 [mudanza] •[mudanza] Por onrra de sant Antruejo To honor Saint Carnival parémonos oy bien anchos, today let’s end up very fat, enbutamos estos panchos, let’s stuff our bellies, rrecalquemos el pellejo, let’s stretch our skin, [vuelta] [vuelta] que constumb’es de conçejo for it’s a custom of the council que todos oy nos hartemos, that today we gorge ourselves, que mañana ayunaremos, for tomorrow we will fast Villancico: “Tarara, tarara” by Antonio de Salazar (1713) A Tarara, tarara qui yo soy Anton Tada, tada, I’m Anthony, Ninglito di nascimiento Black by birth, Qui lo canto lo mas y mijo. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Fleeing Franco’s Spain: Carlos Surinach and Leonardo Balada in the United States (1950–75) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5rk9m7wb Author Wahl, Robert Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Fleeing Franco’s Spain: Carlos Surinach and Leonardo Balada in the United States (1950–75) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Robert J. Wahl August 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Walter A. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Byron Adams Dr. Leonora Saavedra Copyright by Robert J. Wahl 2016 The Dissertation of Robert J. Wahl is approved: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would like to thank the music faculty at the University of California, Riverside, for sharing their expertise in Ibero-American and twentieth-century music with me throughout my studies and the dissertation writing process. I am particularly grateful for Byron Adams and Leonora Saavedra generously giving their time and insight to help me contextualize my work within the broader landscape of twentieth-century music. I would also like to thank Walter Clark, my advisor and dissertation chair, whose encouragement, breadth of knowledge, and attention to detail helped to shape this dissertation into what it is. He is a true role model. This dissertation would not have been possible without the generous financial support of several sources. The Manolito Pinazo Memorial Award helped to fund my archival research in New York and Pittsburgh, and the Maxwell H. -

Kyle E. Jones Purdue University

No. 2, 2014 “SEARCHING AND SEARCHING WE HAVE COME TO FIND”: HISTORIES AND CIRCULATIONS OF HIP HOP IN PERU Kyle E. Jones Purdue University While ethnographic and historiographic research on hip hop has predominantly focused on large metropolises, less attention has been paid to smaller regional cities and the specific ways hip hop travels between urban locales. This paper examines the movements of youth and hip hop practices in Peru, tracing moments of exchange and interaction to contribute an alternative perspective for understanding how hip hop has taken shape across Peru. Such an approach extends the scholarship on hip hop’s socio-spatial dynamics and provides a rich lens through which to understand the ways particular hip hop practices and social forms emerge. Situating the experiences and recollections of hip hoppers from several cities in 1990s and 2000s Peru, while drawing parallels with other forms of expression, also illustrates how hip hop’s histories and circulations reflect longer-standing patterns of mobility, cultural appropriation, and the centrality of expressive forms in navigating changing circumstances of Peruvian urban life. Desde otras ciudades (Arequipa, Puno, Tacna, Cuzco, Canta, Huacho, Barranca, Trujillo, Huancayo, Piura, San Martín, etc.) hay muchísima historia más que contar. (From other cities (Arequipa, Puno, Tacna, Cuzco, Canta, Huacho, Barranca, Trujillo, Huancayo, Piura, San Martín, etc.) there’s so much more history to tell.) -Fakir Kumya Iskaywari, “Historia De HipHop En El Perú” http://alternativas.osu.edu 2, 2014 ISSN 2168-8451 2 kyle e. jones Introduction Analyses of hip hop’s historical contexts, shifts, and continuities have come to occupy a crucial dimension in its growing body of scholarship. -

Production Database Updated As of 25Nov2020

American Composers Orchestra Works Performed Workshopped from 1977-2020 firstname middlename lastname Date eventype venue work title suffix premiere commission year written Michael Abene 4/25/04 Concert LGCH Improv ACO 2004 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Piano Improv Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Violin & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Double Bass & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/9/00 Concert CH Tomorrow's Song, as Yesterday Sings Today World 2000 Ricardo Lorenz Abreu 12/4/94 Concert CH Concierto para orquesta U.S. 1900 John Adams 4/25/83 Concert TULLY Shaker Loops World 1978 John Adams 1/11/87 Concert CH Chairman Dances, The New York ACO-Goelet 1985 John Adams 1/28/90 Concert CH Short Ride in a Fast Machine Albany Symphony 1986 John Adams 12/5/93 Concert CH El Dorado New York Fromm 1991 John Adams 5/17/94 Concert CH Tromba Lontana strings; 3 perc; hp; 2hn; 2tbn; saxophone1900 quartet John Adams 10/8/03 Concert CH Christian Zeal and Activity ACO 1973 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH The Wound-Dresser 1988 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH My Father Knew Charles Ives ACO 2003 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH Violin Concerto 1993 John Luther Adams 10/15/10 Concert ZANKL The Light Within World 2010 Victor Adan 10/16/11 Concert MILLR Tractus World 0 Judah Adashi 10/23/15 Concert ZANKL Sestina World 2015 Julia Adolphe 6/3/14 Reading FISHE Dark Sand, Sifting Light 2014 Kati Agocs 2/20/09 Concert ZANKL Pearls World 2008 Kati Agocs 2/22/09 Concert IHOUS -

Danc-Dance (Danc) 1

DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 DANC 1131. Introduction to Ballroom Dance DANC-DANCE (DANC) 1 Credit (1) Introduction to ballroom dance for non dance majors. Students will learn DANC 1110G. Dance Appreciation basic ballroom technique and partnering work. May be repeated up to 2 3 Credits (3) credits. Restricted to Las Cruces campus only. This course introduces the student to the diverse elements that make up Learning Outcomes the world of dance, including a broad historic overview,roles of the dancer, 1. learn to dance Figures 1-7 in 3 American Style Ballroom dances choreographer and audience, and the evolution of the major genres. 2. develop rhythmic accuracy in movement Students will learn the fundamentals of dance technique, dance history, 3. develop the skills to adapt to a variety of dance partners and a variety of dance aesthetics. Restricted to: Main campus only. Learning Outcomes 4. develop adequate social and recreational dance skills 1. Explain a range of ideas about the place of dance in our society. 5. develop proper carriage, poise, and grace that pertain to Ballroom 2. Identify and apply critical analysis while looking at significant dance dance works in a range of styles. 6. learn to recognize Ballroom music and its application for the 3. Identify dance as an aesthetic and social practice and compare/ appropriate dances contrast dances across a range of historical periods and locations. 7. understand different possibilities for dance variations and their 4. Recognize dance as an embodied historical and cultural artifact, as applications to a variety of Ballroom dances well as a mode of nonverbal expression, within the human experience 8. -

Brazilian Nationalistic Elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2006 Brazilian nationalistic elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda Maria Jose Bernardes Di Cavalcanti Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Di Cavalcanti, Maria Jose Bernardes, "Brazilian nationalistic elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda" (2006). LSU Major Papers. 39. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/39 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRAZILIAN NATIONALISTIC ELEMENTS IN THE BRASILIANAS OF OSVALDO LACERDA A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Maria José Bernardes Di Cavalcanti B.M., Universidade Estadual do Ceará (Brazil), 1987 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2002 December 2006 © Copyright 2006 Maria José Bernardes Di Cavalcanti All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This monograph is dedicated to my husband Liduino José Pitombeira de Oliveira, for being my inspiration and for encouraging me during these years -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Break Down Borders

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SAN DIEGO Break Down Borders: Translocal Intimacies in Contemporary San Diego///Tijuana Border Activisms A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnic Studies by Leslie Quintanilla Committee in charge: Professor Fatima El-Tayeb, Chair Professor Kirstie Dorr Professor Yen Le Espiritu Professor Jillian Hernandez Professor Bradley Werner Professor K. Wayne Yang 2019 Copyright Leslie Quintanilla, 2019 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Leslie Quintanilla is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________ Chair University of California San Diego 2019 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page……………………………………….……….………..…….………….……..…………………………..iii Table of Contents………………………………………….…………..………..…….…………..……………………….iv List of Figures…………………………………………………………………………………….…………………………vi Acknowledgements…………….…………………………………………….…………….……..……………………...vii Curriculum Vitae………………………………………………………….…….……..………..……………………….….x Abstract of the Dissertation…………………………………………….……..……….……………………………...xv Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...1 Chapter -

Nuevo Flamenco: Re-Imagining Flamenco in Post-Dictatorship Spain

Nuevo Flamenco: Re-imagining Flamenco in Post-dictatorship Spain Xavier Moreno Peracaula Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of PhD Newcastle University March 2016 ii Contents Abstract iv Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Chapter One The Gitano Atlantic: the Impact of Flamenco in Modal Jazz and its Reciprocal Influence in the Origins of Nuevo Flamenco 21 Introduction 22 Making Sketches: Flamenco and Modal Jazz 29 Atlantic Crossings: A Signifyin(g) Echo 57 Conclusions 77 Notes 81 Chapter Two ‘Gitano Americano’: Nuevo Flamenco and the Re-imagining of Gitano Identity 89 Introduction 90 Flamenco’s Racial Imagination 94 The Gitano Stereotype and its Ambivalence 114 Hyphenated Identity: the Logic of Splitting and Doubling 123 Conclusions 144 Notes 151 Chapter Three Flamenco Universal: Circulating the Authentic 158 Introduction 159 Authentic Flamenco, that Old Commodity 162 The Advent of Nuevo Flamenco: Within and Without Tradition 184 Mimetic Sounds 205 Conclusions 220 Notes 224 Conclusions 232 List of Tracks on Accompanying CD 254 Bibliography 255 Discography 270 iii Abstract This thesis is concerned with the study of nuevo flamenco (new flamenco) as a genre characterised by the incorporation within flamenco of elements from music genres of the African-American musical traditions. A great deal of emphasis is placed on purity and its loss, relating nuevo flamenco with the whole history of flamenco and its discourses, as well as tracing its relationship to other musical genres, mainly jazz. While centred on the process of fusion and crossover it also explores through music the characteristics and implications that nuevo flamenco and its discourses have impinged on related issues as Gypsy identity and cultural authenticity.