PROGRAM NOTES Anton Webern Passacaglia for Orchestra, Op. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard's First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino

Twentieth-Century Music 16/3, 557–588 © Cambridge University Press 2019. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi: 10.1017/S1478572219000306 A Heretic in the Schoenberg Circle: Roberto Gerhard’s First Engagement with Twelve-Tone Procedures in Andantino DIEGO ALONSO TOMÁS Abstract Shortly before finishing his studies with Arnold Schoenberg, Roberto Gerhard composed Andantino,a short piece in which he used for the first time a compositional technique for the systematic circu- lation of all pitch classes in both the melodic and the harmonic dimensions of the music. He mod- elled this technique on the tri-tetrachordal procedure in Schoenberg’s Prelude from the Suite for Piano, Op. 25 but, unlike his teacher, Gerhard treated the tetrachords as internally unordered pitch-class collections. This decision was possibly encouraged by his exposure from the mid- 1920s onwards to Josef Matthias Hauer’s writings on ‘trope theory’. Although rarely discussed by scholars, Andantino occupies a special place in Gerhard’s creative output for being his first attempt at ‘twelve-tone composition’ and foreshadowing the permutation techniques that would become a distinctive feature of his later serial compositions. This article analyses Andantino within the context of the early history of twelve-tone music and theory. How well I do remember our Berlin days, what a couple we made, you and I; you (at that time) the anti-Schoenberguian [sic], or the very reluctant Schoenberguian, and I, the non-conformist, or the Schoenberguian malgré moi. -

View PDF Document

Society of Composers Inc. National Student Conference 2001 Presented by The Indiana School of Music welcomes you to the 2001 Society of Composers Inc. National Student Conference Dear Composers and Friends: I am pleased to attend the Third Annual National Student Conference of the Society of Composers, Inc. This event, ably hosted by Jason Bahr with generous support from Don Freund, will give you that rare opportunity to meet and hear each other's works performed by some of the most talented performers in this country. Take advantage of this timethese are your future colleagues, for you can never predict when you will meet them again. This is the weekend we will choose the three winners of the SCI/ASCAP Student Composition Commission Competition, to be announced at the banquet on Saturday evening. You will hear three new compositions by the winners of the 2000 competition: Lansing D. McLoskey's new choral work on Saturday at 4:00 p.m.; Karim Al-Zand's Wind Ensemble work to be performed Thursday night at 8:00 p.m.; and Ching-chu Hu's chamber ensemble work on the Friday night concert. SCI is grateful to Fran Richard and ASCAP for their support with this ongoing commissioning project. Last month I was asked by the editor of the on-line journal at the American Music Center in New York to discuss the dominant musical style of today and to predict what the dominant musical style might be of tomorrow. If only I could predict future trends! And yet, today's music depends upon whom you ask. -

Passacaglia PRINT

On Shifting Grounds: Meandering, Modulating, and Möbius Passacaglias David Feurzeig Passacaglias challenge a prevailing assumption underlying traditional tonal analysis: that tonal motion proceeds along a unidirectional “arrow of time.” The term “continuous variation,” which describes characteristic passacaglia technique in contrast to sectional “Theme and Variations” movements, suggests as much: the musical impetus continues forward even as the underlying progression circles back to its starting point. A passacaglia describes a kind of loop. 1 But the loop of a traditional passacaglia is a rather flattened one, ovoid rather than circular. For most of the pattern, the tonal motion proceeds in one direction—from tonic to dominant—then quickly drops back to the tonic, like a skier going gradually up and rapidly down a slope. The looping may be smoother in tonic-requiring passacaglia themes (those which end on the dominant) than in tonic- providing themes, as the dominant harmony propels the music across the “seam” between successive statements of the harmonic pattern. But in both types, a clear dominant-tonic cadence tends to work against a sense of seamless circularity. This is not the case for some more recent passacaglias. A modern compositional type, which to my knowledge has not been discussed before as such, is the modulatory passacaglia.2 Modulating passacaglia themes subvert tonal closure via progressions which employ elements of traditional tonality but veer away from the putative tonal center. Passacaglias built on these themes may take on a more truly circular form, with no obvious start or endpoint. This structural ambiguity is foreshadowed in some Baroque ground-bass compositions. -

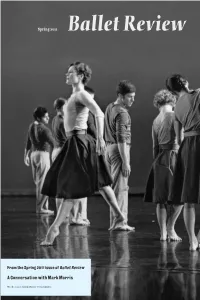

A Conversation with Mark Morris

Spring2011 Ballet Review From the Spring 2011 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Mark Morris On the cover: Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. 4 Paris – Peter Sparling 6 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 8 Stupgart – Gary Smith 10 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 13 Paris – Peter Sparling 15 Sarasota, FL – Joseph Houseal 17 Paris – Peter Sparling 19 Toronto – Gary Smith 20 Paris – Leigh Witchel 40 Joel Lobenthal 24 A Conversation with Cynthia Gregory Joseph Houseal 40 Lady Aoi in New York Elizabeth Souritz 48 Balanchine in Russia 61 Daniel Gesmer Ballet Review 39.1 56 A Conversation with Spring 2011 Bruce Sansom Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Sandra Genter 61 Next Wave 2010 Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman Michael Porter Senior Editor: Don Daniels 68 Swan Lake II Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Darrell Wilkins 48 70 Cherkaoui and Waltz Associate Editor: Larry Kaplan Joseph Houseal Copy Editor: 76 A Conversation with Barbara Palfy Mark Morris Photographers: Tom Brazil Costas 87 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Associates: Peter Anastos 100 Check It Out Robert Greskovic George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall 70 Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Supon David Vaughan Edward Willinger Sarah C. Woodcock CoverphotobyTomBrazil: MarkMorris’FestivalDance. Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. (Photos: Tom Brazil) 76 ballet review A Conversation with – Plato and Satie – was a very white piece. Morris: I’m postracial. Mark Morris BR: I like white. I’m not against white. Morris:Famouslyornotfamously,Satiesaid that he wanted that piece of music to be as Joseph Houseal “white as classical antiquity,”not knowing, of course, that the Parthenon was painted or- BR: My first question is . -

Female Composer Segment Catalogue

FEMALE CLASSICAL COMPOSERS from past to present ʻFreed from the shackles and tatters of the old tradition and prejudice, American and European women in music are now universally hailed as important factors in the concert and teaching fields and as … fast developing assets in the creative spheres of the profession.’ This affirmation was made in 1935 by Frédérique Petrides, the Belgian-born female violinist, conductor, teacher and publisher who was a pioneering advocate for women in music. Some 80 years on, it’s gratifying to note how her words have been rewarded with substance in this catalogue of music by women composers. Petrides was able to look back on the foundations laid by those who were well-connected by family name, such as Clara Schumann and Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, and survey the crop of composers active in her own time, including Louise Talma and Amy Beach in America, Rebecca Clarke and Liza Lehmann in England, Nadia Boulanger in France and Lou Koster in Luxembourg. She could hardly have foreseen, however, the creative explosion in the latter half of the 20th century generated by a whole new raft of female composers – a happy development that continues today. We hope you will enjoy exploring this catalogue that has not only historical depth but a truly international voice, as exemplified in the works of the significant number of 21st-century composers: be it the highly colourful and accessible American chamber music of Jennifer Higdon, the Asian hues of Vivian Fung’s imaginative scores, the ancient-and-modern syntheses of Sofia Gubaidulina, or the hallmark symphonic sounds of the Russian-born Alla Pavlova. -

Music in the “New World”: from New Spain to New England Objectives

Music in the “New World”: From New Spain to New England objectives I. the villancico in Peru (what’s new about it) II. Spanish opera in Peru III. music in the British colonies [focus on the terms and the two works on your listening list] The “Age of Discovery” (for Europeans) • 1492: Christopher Columbus (Spain) • 1494: Treaty of Tordesillas • 1500: “discovery” of Brazil by Portuguese 1 Pre‐Columbian Civilizations • Mayans (Guatemala, 4th‐8th c.) • Aztecs (Mexico, late 12th c.‐1521) • Incas (Peru, 13th c.‐1533) music of Pre‐Columbian Civilizations • NO music survives • Music Sources: – 1. surviving instruments – 2. iconography – 3. writings about music by missionaries • music was inseparable from religious ritual 1. Surviving Instruments Aztec Flutes Incan stone panpipe 2 2. Iconography “New World” 17th‐18th c. Sacred Music in Hispanic America • Catholic liturgical music – tool for evangelism • Masses, Motets, etc. (in Latin) – Prima prattica works influenced by “Golden Age of Spanish Polyphony” • Cristóbal Morales • Tomás Luis de Victoria 3 Sacred Music in New Spain (Mexico) • Villancico – strophic song in Spanish with refrain Estribillo (refrain) Copla (strophe) A b b a or A Juan del Encina: Oy comamos y bebamos, villancico (late 15th cent.) • Estrebillo: • Refrain: Oy comamos y bebamos Today let’s eat and drink y cantemos y holguemos, and sing and have a good time que mañana ayunaremos. for tomorrow we will fast. • Copla 1 • Stanza 1 [mudanza] •[mudanza] Por onrra de sant Antruejo To honor Saint Carnival parémonos oy bien anchos, today let’s end up very fat, enbutamos estos panchos, let’s stuff our bellies, rrecalquemos el pellejo, let’s stretch our skin, [vuelta] [vuelta] que constumb’es de conçejo for it’s a custom of the council que todos oy nos hartemos, that today we gorge ourselves, que mañana ayunaremos, for tomorrow we will fast Villancico: “Tarara, tarara” by Antonio de Salazar (1713) A Tarara, tarara qui yo soy Anton Tada, tada, I’m Anthony, Ninglito di nascimiento Black by birth, Qui lo canto lo mas y mijo. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Fleeing Franco’s Spain: Carlos Surinach and Leonardo Balada in the United States (1950–75) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5rk9m7wb Author Wahl, Robert Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Fleeing Franco’s Spain: Carlos Surinach and Leonardo Balada in the United States (1950–75) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Robert J. Wahl August 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Walter A. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Byron Adams Dr. Leonora Saavedra Copyright by Robert J. Wahl 2016 The Dissertation of Robert J. Wahl is approved: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would like to thank the music faculty at the University of California, Riverside, for sharing their expertise in Ibero-American and twentieth-century music with me throughout my studies and the dissertation writing process. I am particularly grateful for Byron Adams and Leonora Saavedra generously giving their time and insight to help me contextualize my work within the broader landscape of twentieth-century music. I would also like to thank Walter Clark, my advisor and dissertation chair, whose encouragement, breadth of knowledge, and attention to detail helped to shape this dissertation into what it is. He is a true role model. This dissertation would not have been possible without the generous financial support of several sources. The Manolito Pinazo Memorial Award helped to fund my archival research in New York and Pittsburgh, and the Maxwell H. -

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First I

An Examination of Minimalist Tendencies in Two Early Works by Terry Riley Ann Glazer Niren Indiana University Southeast First International Conference on Music and Minimalism University of Wales, Bangor Friday, August 31, 2007 Minimalism is perhaps one of the most misunderstood musical movements of the latter half of the twentieth century. Even among musicians, there is considerable disagreement as to the meaning of the term “minimalism” and which pieces should be categorized under this broad heading.1 Furthermore, minimalism is often referenced using negative terminology such as “trance music” or “stuck-needle music.” Yet, its impact cannot be overstated, influencing both composers of art and rock music. Within the original group of minimalists, consisting of La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass2, the latter two have received considerable attention and many of their works are widely known, even to non-musicians. However, Terry Riley is one of the most innovative members of this auspicious group, and yet, he has not always received the appropriate recognition that he deserves. Most musicians familiar with twentieth century music realize that he is the composer of In C, a work widely considered to be the piece that actually launched the minimalist movement. But is it really his first minimalist work? Two pieces that Riley wrote early in his career as a graduate student at Berkeley warrant closer attention. Riley composed his String Quartet in 1960 and the String Trio the following year. These two works are virtually unknown today, but they exhibit some interesting minimalist tendencies and indeed foreshadow some of Riley’s later developments. -

Production Database Updated As of 25Nov2020

American Composers Orchestra Works Performed Workshopped from 1977-2020 firstname middlename lastname Date eventype venue work title suffix premiere commission year written Michael Abene 4/25/04 Concert LGCH Improv ACO 2004 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Piano Improv Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Violin & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Double Bass & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/9/00 Concert CH Tomorrow's Song, as Yesterday Sings Today World 2000 Ricardo Lorenz Abreu 12/4/94 Concert CH Concierto para orquesta U.S. 1900 John Adams 4/25/83 Concert TULLY Shaker Loops World 1978 John Adams 1/11/87 Concert CH Chairman Dances, The New York ACO-Goelet 1985 John Adams 1/28/90 Concert CH Short Ride in a Fast Machine Albany Symphony 1986 John Adams 12/5/93 Concert CH El Dorado New York Fromm 1991 John Adams 5/17/94 Concert CH Tromba Lontana strings; 3 perc; hp; 2hn; 2tbn; saxophone1900 quartet John Adams 10/8/03 Concert CH Christian Zeal and Activity ACO 1973 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH The Wound-Dresser 1988 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH My Father Knew Charles Ives ACO 2003 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH Violin Concerto 1993 John Luther Adams 10/15/10 Concert ZANKL The Light Within World 2010 Victor Adan 10/16/11 Concert MILLR Tractus World 0 Judah Adashi 10/23/15 Concert ZANKL Sestina World 2015 Julia Adolphe 6/3/14 Reading FISHE Dark Sand, Sifting Light 2014 Kati Agocs 2/20/09 Concert ZANKL Pearls World 2008 Kati Agocs 2/22/09 Concert IHOUS -

Webern's "Middle Period": Body of the Mother Or Law of the Father?

Webern's "Middle Period": Body of the Mother or Law of the Father? Julian Johnson I Introduction: Webern Reception Webern occupies an almost unique position in the canon of Western composers. In few cases is there such disproportion between the degree of interest in talking about the music and that in actually performing it or listening to it. After his death in 1945 he had the misfortune to become a banner, a slogan essentially the name that marked a certain polemical position in contemporary musical debate. Fifty years later the image in which he was cast during the decade after his death remains largely unchanged. His music continues to be primarily associ ated with the idea of the most rigorous intellectual order. His use of serialism is held up as the apogee of the cerebral, quasi mathematical organization of musical sound in which the prin ciples of logic, symmetry, and formal economy displace any of the residues of late-romantic "expression" that may still be traced in his early works. Webern the serialist thus becomes the embodiment of Paternal Law applied to music: the hetero geneous element of art is excised in the name of coherence, as the musical material seeks to realize a "purity" whose political implications in the context of Web ern's social milieu have not been missed. Webernian serialism, and the musical culture which it unwittingly fathered post-1945, might well be cited as the embodiment of a patriarchal order in musical form. In Kristevan terminology, it is the almost total repression of the 61 62 Johnson Webern's "Middle Period" semiotic, an attempt to establish a syntactical Symbolic Order which has eliminated every trace of heterogeneous, material content. -

Brazilian Nationalistic Elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2006 Brazilian nationalistic elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda Maria Jose Bernardes Di Cavalcanti Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Di Cavalcanti, Maria Jose Bernardes, "Brazilian nationalistic elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda" (2006). LSU Major Papers. 39. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/39 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRAZILIAN NATIONALISTIC ELEMENTS IN THE BRASILIANAS OF OSVALDO LACERDA A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Maria José Bernardes Di Cavalcanti B.M., Universidade Estadual do Ceará (Brazil), 1987 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2002 December 2006 © Copyright 2006 Maria José Bernardes Di Cavalcanti All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This monograph is dedicated to my husband Liduino José Pitombeira de Oliveira, for being my inspiration and for encouraging me during these years -

978 1 84694 924 1 Infinite Music Txt Revise:Layout 1.Qxd

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Harper, A. (2011). Introduction. In: Harper, A. (Ed.), Infinite Music: Imaging the Next Millennium of Human Music-Making. (pp. 1-14). Winchester, UK: John Hunt Publishing. ISBN 1846949246 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/15588/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Introduction: All Worlds ‘To the makers of music – all worlds, all times’ – handwritten inscription on the Voyager Golden Record There’s a legend that sometime in the early nineteen-twenties Arnold Schoenberg, the Austrian composer regarded by many as the defining figure of musical modernism, proudly announced to his pupils Alban Berg and Anton Webern his discovery of a new compositional technique that would ensure the dominance of the German musical tradition for a thousand years.