Passacaglia PRINT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innovative Approaches to Melodic Elaboration in Contemporary Tabuh Kreasibaru

INNOVATIVE APPROACHES TO MELODIC ELABORATION IN CONTEMPORARY TABUH KREASIBARU by PETER MICHAEL STEELE B.A., Pitzer College, 2003 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Music) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2007 © Peter Michael Steele, 2007 ABSTRACT The following thesis has two goals. The first is to present a comparison of recent theories of Balinese music, specifically with regard to techniques of melodic elaboration. By comparing the work of Wayan Rai, Made Bandem, Wayne Vitale, and Michael Tenzer, I will investigate how various scholars choose to conceptualize melodic elaboration in modern genres of Balinese gamelan. The second goal is to illustrate the varying degrees to which contemporary composers in the form known as Tabuh Kreasi are expanding this musical vocabulary. In particular I will examine their innovative approaches to melodic elaboration. Analysis of several examples will illustrate how some composers utilize and distort standard compositional techniques in an effort to challenge listeners' expectations while still adhering to indigenous concepts of balance and flow. The discussion is preceded by a critical reevaluation of the function and application of the western musicological terms polyphony and heterophony. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents : iii List of Tables .... '. iv List of Figures ' v Acknowledgements vi CHAPTER 1 Introduction and Methodology • • • • • :•-1 Background : 1 Analysis: Some Recent Thoughts 4 CHAPTER 2 Many or just Different?: A Lesson in Categorical Cacophony 11 Polyphony Now and Then 12 Heterophony... what is it, exactly? 17 CHAPTER 3 Historical and Theoretical Contexts 20 Introduction 20 Melodic Elaboration in History, Theory and Process ..' 22 Abstraction and Elaboration 32 Elaboration Types 36 Constructing Elaborations 44 Issues of "Feeling". -

View PDF Document

Society of Composers Inc. National Student Conference 2001 Presented by The Indiana School of Music welcomes you to the 2001 Society of Composers Inc. National Student Conference Dear Composers and Friends: I am pleased to attend the Third Annual National Student Conference of the Society of Composers, Inc. This event, ably hosted by Jason Bahr with generous support from Don Freund, will give you that rare opportunity to meet and hear each other's works performed by some of the most talented performers in this country. Take advantage of this timethese are your future colleagues, for you can never predict when you will meet them again. This is the weekend we will choose the three winners of the SCI/ASCAP Student Composition Commission Competition, to be announced at the banquet on Saturday evening. You will hear three new compositions by the winners of the 2000 competition: Lansing D. McLoskey's new choral work on Saturday at 4:00 p.m.; Karim Al-Zand's Wind Ensemble work to be performed Thursday night at 8:00 p.m.; and Ching-chu Hu's chamber ensemble work on the Friday night concert. SCI is grateful to Fran Richard and ASCAP for their support with this ongoing commissioning project. Last month I was asked by the editor of the on-line journal at the American Music Center in New York to discuss the dominant musical style of today and to predict what the dominant musical style might be of tomorrow. If only I could predict future trends! And yet, today's music depends upon whom you ask. -

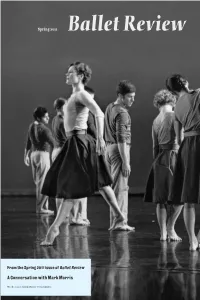

A Conversation with Mark Morris

Spring2011 Ballet Review From the Spring 2011 issue of Ballet Review A Conversation with Mark Morris On the cover: Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. 4 Paris – Peter Sparling 6 Boston – Jeffrey Gantz 8 Stupgart – Gary Smith 10 San Francisco – Leigh Witchel 13 Paris – Peter Sparling 15 Sarasota, FL – Joseph Houseal 17 Paris – Peter Sparling 19 Toronto – Gary Smith 20 Paris – Leigh Witchel 40 Joel Lobenthal 24 A Conversation with Cynthia Gregory Joseph Houseal 40 Lady Aoi in New York Elizabeth Souritz 48 Balanchine in Russia 61 Daniel Gesmer Ballet Review 39.1 56 A Conversation with Spring 2011 Bruce Sansom Editor and Designer: Marvin Hoshino Sandra Genter 61 Next Wave 2010 Managing Editor: Roberta Hellman Michael Porter Senior Editor: Don Daniels 68 Swan Lake II Associate Editor: Joel Lobenthal Darrell Wilkins 48 70 Cherkaoui and Waltz Associate Editor: Larry Kaplan Joseph Houseal Copy Editor: 76 A Conversation with Barbara Palfy Mark Morris Photographers: Tom Brazil Costas 87 London Reporter – Clement Crisp 94 Music on Disc – George Dorris Associates: Peter Anastos 100 Check It Out Robert Greskovic George Jackson Elizabeth Kendall 70 Paul Parish Nancy Reynolds James Supon David Vaughan Edward Willinger Sarah C. Woodcock CoverphotobyTomBrazil: MarkMorris’FestivalDance. Mark Morris’ Festival Dance. (Photos: Tom Brazil) 76 ballet review A Conversation with – Plato and Satie – was a very white piece. Morris: I’m postracial. Mark Morris BR: I like white. I’m not against white. Morris:Famouslyornotfamously,Satiesaid that he wanted that piece of music to be as Joseph Houseal “white as classical antiquity,”not knowing, of course, that the Parthenon was painted or- BR: My first question is . -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE JAVANESE WAYANG KULIT PERFORMED IN THE CLASSIC PALACE STYLE: AN ANALYSIS OF RAMA’S CROWN AS TOLD BY KI PURBO ASMORO A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By GUAN YU, LAM Norman, Oklahoma 2016 JAVANESE WAYANG KULIT PERFORMED IN THE CLASSIC PALACE STYLE: AN ANALYSIS OF RAMA’S CROWN AS TOLD BY KI PURBO ASMORO A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ______________________________ Dr. Paula Conlon, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Eugene Enrico ______________________________ Dr. Marvin Lamb © Copyright by GUAN YU, LAM 2016 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I would like to take this opportunity to thank the members of my committee: Dr. Paula Conlon, Dr. Eugene Enrico, and Dr. Marvin Lamb for their guidance and suggestions in the preparation of this thesis. I would especially like to thank Dr. Paula Conlon, who served as chair of the committee, for the many hours of reading, editing, and encouragement. I would also like to thank Wong Fei Yang, Thow Xin Wei, and Agustinus Handi for selflessly sharing their knowledge and helping to guide me as I prepared this thesis. Finally, I would like to thank my family and friends for their continued support throughout this process. iv Table of Contents Acknowledgements ......................................................................................................... iv List of Figures ............................................................................................................... -

Music in the “New World”: from New Spain to New England Objectives

Music in the “New World”: From New Spain to New England objectives I. the villancico in Peru (what’s new about it) II. Spanish opera in Peru III. music in the British colonies [focus on the terms and the two works on your listening list] The “Age of Discovery” (for Europeans) • 1492: Christopher Columbus (Spain) • 1494: Treaty of Tordesillas • 1500: “discovery” of Brazil by Portuguese 1 Pre‐Columbian Civilizations • Mayans (Guatemala, 4th‐8th c.) • Aztecs (Mexico, late 12th c.‐1521) • Incas (Peru, 13th c.‐1533) music of Pre‐Columbian Civilizations • NO music survives • Music Sources: – 1. surviving instruments – 2. iconography – 3. writings about music by missionaries • music was inseparable from religious ritual 1. Surviving Instruments Aztec Flutes Incan stone panpipe 2 2. Iconography “New World” 17th‐18th c. Sacred Music in Hispanic America • Catholic liturgical music – tool for evangelism • Masses, Motets, etc. (in Latin) – Prima prattica works influenced by “Golden Age of Spanish Polyphony” • Cristóbal Morales • Tomás Luis de Victoria 3 Sacred Music in New Spain (Mexico) • Villancico – strophic song in Spanish with refrain Estribillo (refrain) Copla (strophe) A b b a or A Juan del Encina: Oy comamos y bebamos, villancico (late 15th cent.) • Estrebillo: • Refrain: Oy comamos y bebamos Today let’s eat and drink y cantemos y holguemos, and sing and have a good time que mañana ayunaremos. for tomorrow we will fast. • Copla 1 • Stanza 1 [mudanza] •[mudanza] Por onrra de sant Antruejo To honor Saint Carnival parémonos oy bien anchos, today let’s end up very fat, enbutamos estos panchos, let’s stuff our bellies, rrecalquemos el pellejo, let’s stretch our skin, [vuelta] [vuelta] que constumb’es de conçejo for it’s a custom of the council que todos oy nos hartemos, that today we gorge ourselves, que mañana ayunaremos, for tomorrow we will fast Villancico: “Tarara, tarara” by Antonio de Salazar (1713) A Tarara, tarara qui yo soy Anton Tada, tada, I’m Anthony, Ninglito di nascimiento Black by birth, Qui lo canto lo mas y mijo. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Fleeing Franco’s Spain: Carlos Surinach and Leonardo Balada in the United States (1950–75) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5rk9m7wb Author Wahl, Robert Publication Date 2016 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Fleeing Franco’s Spain: Carlos Surinach and Leonardo Balada in the United States (1950–75) A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Robert J. Wahl August 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Walter A. Clark, Chairperson Dr. Byron Adams Dr. Leonora Saavedra Copyright by Robert J. Wahl 2016 The Dissertation of Robert J. Wahl is approved: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would like to thank the music faculty at the University of California, Riverside, for sharing their expertise in Ibero-American and twentieth-century music with me throughout my studies and the dissertation writing process. I am particularly grateful for Byron Adams and Leonora Saavedra generously giving their time and insight to help me contextualize my work within the broader landscape of twentieth-century music. I would also like to thank Walter Clark, my advisor and dissertation chair, whose encouragement, breadth of knowledge, and attention to detail helped to shape this dissertation into what it is. He is a true role model. This dissertation would not have been possible without the generous financial support of several sources. The Manolito Pinazo Memorial Award helped to fund my archival research in New York and Pittsburgh, and the Maxwell H. -

Production Database Updated As of 25Nov2020

American Composers Orchestra Works Performed Workshopped from 1977-2020 firstname middlename lastname Date eventype venue work title suffix premiere commission year written Michael Abene 4/25/04 Concert LGCH Improv ACO 2004 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Piano Improv Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Violin & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/6/00 Concert JOESP Duet for Double Bass & Piano Earshot-JCOI 19 Muhal Richard Abrams 1/9/00 Concert CH Tomorrow's Song, as Yesterday Sings Today World 2000 Ricardo Lorenz Abreu 12/4/94 Concert CH Concierto para orquesta U.S. 1900 John Adams 4/25/83 Concert TULLY Shaker Loops World 1978 John Adams 1/11/87 Concert CH Chairman Dances, The New York ACO-Goelet 1985 John Adams 1/28/90 Concert CH Short Ride in a Fast Machine Albany Symphony 1986 John Adams 12/5/93 Concert CH El Dorado New York Fromm 1991 John Adams 5/17/94 Concert CH Tromba Lontana strings; 3 perc; hp; 2hn; 2tbn; saxophone1900 quartet John Adams 10/8/03 Concert CH Christian Zeal and Activity ACO 1973 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH The Wound-Dresser 1988 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH My Father Knew Charles Ives ACO 2003 John Adams 4/27/07 Concert CH Violin Concerto 1993 John Luther Adams 10/15/10 Concert ZANKL The Light Within World 2010 Victor Adan 10/16/11 Concert MILLR Tractus World 0 Judah Adashi 10/23/15 Concert ZANKL Sestina World 2015 Julia Adolphe 6/3/14 Reading FISHE Dark Sand, Sifting Light 2014 Kati Agocs 2/20/09 Concert ZANKL Pearls World 2008 Kati Agocs 2/22/09 Concert IHOUS -

Brazilian Nationalistic Elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Major Papers Graduate School 2006 Brazilian nationalistic elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda Maria Jose Bernardes Di Cavalcanti Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Di Cavalcanti, Maria Jose Bernardes, "Brazilian nationalistic elements in the Brasilianas of Osvaldo Lacerda" (2006). LSU Major Papers. 39. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_majorpapers/39 This Major Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Major Papers by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BRAZILIAN NATIONALISTIC ELEMENTS IN THE BRASILIANAS OF OSVALDO LACERDA A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Maria José Bernardes Di Cavalcanti B.M., Universidade Estadual do Ceará (Brazil), 1987 M.M., Louisiana State University, 2002 December 2006 © Copyright 2006 Maria José Bernardes Di Cavalcanti All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This monograph is dedicated to my husband Liduino José Pitombeira de Oliveira, for being my inspiration and for encouraging me during these years -

PROGRAM NOTES Anton Webern Passacaglia for Orchestra, Op. 1

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Anton Webern Born December 2, 1883, Vienna, Austria. Died September 15, 1945, Mittersill, near Salzburg, Austria. Passacaglia for Orchestra, Op. 1 Webern composed his Passacaglia in 1908 and conducted the first performance in Vienna that year. The score calls for two flutes and piccolo, two oboes and english horn, two clarinets and bass clarinet, two bassoons and contrabassoon, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones and tuba, timpani, cymbals, bass drum, triangle, tam-tam, harp, and strings. Performance time is approximately eleven minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Webern’s Passacaglia were given at Orchestra Hall on February 10 and 11, 1944, with Désiré Defauw conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given on November 25, 26, and 27, 1994, with Pierre Boulez conducting. The Orchestra first performed this work at the Ravinia Festival on July 28, 1990, with Gianluigi Gelmetti conducting, and most recently on July 22, 2000, with Bernhard Klee conducting. Op. 1 is a composer’s calling card—the earliest music that he officially sends out into the world. For every composer like Franz Schubert, whose first published work (the song Der Erlkönig) is a masterpiece that he will often equal but seldom surpass, there are countless others for whom op. 1 scarcely conveys what later years will bring. Orchestral music bearing op. 1 has seldom stayed in the repertory; it usually is followed by music which is better, more popular, and more characteristic—who today hears Stravinsky’s Symphony in E-flat, Richard Strauss’s Festmarsch, or Shostakovich’s Scherzo in F-sharp? Anton Webern’s op. -

LEEDSLIEDER+ Friday 2 October – Sunday 4 October 2009 Filling the City with Song!

LEEDSLIEDER+ Friday 2 October – Sunday 4 October 2009 Filling the city with song! Festival Programme 2009 The Grammar School at Leeds inspiring individuals is pleased to support the Leeds Lieder+ Festival Our pupils aren’t just pupils. singers, They’re also actors, musicians, stagehands, light & sound technicians, comedians, , impressionists, producers, graphic artists, playwrightsbox office managers… ...sometimes they even sit exams! www.gsal.org.uk For admissions please call 0113 228 5121 Come along and see for yourself... or email [email protected] OPENING MORNING Saturday 17 October 9am - 12noon LEEDSLIEDER+ Friday 2 October – Sunday 4 October 2009 Biennial Festival of Art Song Artistic Director Julius Drake 3 Lord Harewood Elly Ameling If you, like me, have collected old gramophone records from Dear Friends of Leeds Lieder+ the time you were at school, you will undoubtedly have a large I am sure that you will have a great experience listening to this number of Lieder performances amongst them. Each one year’s rich choice of concerts and classes. It has become a is subtly different from its neighbour and that is part of the certainty! attraction. I know what I miss: alas, circumstances at home prevent me The same will be apparent in the performances which you this time from being with you and from nourishing my soul with will hear under the banner of Leeds Lieder+ and I hope this the music in Leeds. variety continues to give you the same sort of pleasure as Lieder singing always has in the past. I feel pretty sure that it To the musicians and to the audience as well I would like to will and that if you have any luck the memorable will become repeat the words that the old Josef Krips said to me right indistinguishable from the category of ‘great’. -

FALL 2009 87 Fugue, Hip Hop and Soap Opera

FALL 2009 87 Fugue, Hip Hop and Soap Opera: Transcultural Connections and Theatrical Experimentation in Twenty-First Century US Latina Playwriting Anne García-Romero A tension can exist between theatrical experimentation and commercial viability. If a playwright writes a play which challenges traditional notions of structure, character and language, will her play get produced? If her play solely adheres to hegemonic, dramaturgical norms, is it more likely to get produced? Early twenty-first century Latina playwrights are writing plays with fractured narratives, multi-cultural characters and linguistic hybridities. In this essay, through examining Elliot, A Soldier’s Fugue by Quiara Alegría Hudes, Tropic of X by Caridad Svich and Fuente by Cusi Cram, I propose that these playwrights’ theatrical experimentations, created by exploring and subverting diverse artistic models, reflect the dynamics of transculturation and that the resulting plays are not only commercially viable but vital to twenty-first century US theater. Hudes, a Yale-trained composer, utilizes compositional fugue structure in her play, Elliot, A Soldier’s Fugue as she delves into the life of a Puerto Rican veteran from Philadelphia confronting a second tour of duty in Iraq. A fugue consists of a composition for multiple voices or instruments in which “a subject is stated unaccompanied in a single voice (or instrument). Then a second voice enters with the answer…The original voice continues with the counterpoint against the answer. After this a third voice enters in turn with the subject again while the first two voices continue with counterpoint against it. Finally, a fourth voice enters, now with the answer, while all three of the other voices accompany it with counterpoint” (Verrall ix). -

Recital Programs for Fall Semester 2002 Music Department

Eastern Illinois University The Keep General and Sophomore Recitals Concerts and Recitals Fall 2002 All Recital Programs for Fall Semester 2002 Music Department Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/recitals_general Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Music Department, "All Recital Programs for Fall Semester 2002" (2002). General and Sophomore Recitals. 4. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/recitals_general/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Concerts and Recitals at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in General and Sophomore Recitals by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Music Department presents a General Recital Romance Camille Saint-Saëns October 22, 2002 (1835-1921) 2:00 p.m. Edwin Ochsner, horn Alexis Ignatiou, piano McAfee Gymnasium North Prelude and Scherzo Neil Butterworth PROGRAM (b. 1934) Laney Grimes, horn Jason Yarcho, piano Concerto in f minor G. F. Handel (1685-1759) arr. Keith Brown From the Shores of the Mighty Pacific Herbert L. Clarke Grave (1867-1945) Allegro Sarabande Andy Messerli, euphonium Allegro Jennifer Colgan, piano Brad Wallace, trombone Jennifer Colgan, piano Adagio in D flat Major Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Abigail Heras, organ EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY Music Department presents a General Recital November 5, 2002 2:00 p.m. McAfee Gymnasium North “Unis dès la plus tendre enfance” C. W. Gluck (Iphigénie en Tauride) (1714-1787) “Vainement ma bien-aimée” (Le Roi d’Ys) Edouard Lalo PROGRAM (1813-1901) Lucas Goodrich, tenor Piéce en mi bémol, Op. 33 Henri Büsser Rachel Warfel, piano (1872-1973) Andy Messerli, euphonium “Che farò senza Euridice” (Orfeo ed Euridice) C.