CHAPTER THREE Into the Fray

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brij Lal's Biography of AD Patel

18 Fijian Studies Vol 13, No. 1 tory cannot be written without some bias and selective emphasis. The book well illustrates historian David Lowenthal’s dictum: ‘History is per- suasive because it is organised by and filtered through individual minds, not in spite of that fact. Subjective interpretation gives it life and mean- Brij Lal's Biography of A D Patel - A Vision for Change: ing’ (1985: 218). A.D. Patel and the Politics of Fiji Chapter 1, Retrospect, sketches the emergence of Indian society and politics in Fiji - the setting into which Patel stepped at the age of only 23 Robert Norton in 1928, soon to join the leadership of the campaign for political equality with the minority European community under a common roll electoral 3 system. The common franchise campaign was abandoned in the early A.D. Patel and Ratu Kamisese Mara were the outstanding political 1930s and not revived until the 1960s, this time with Patel in the lead. leaders and adversaries during Fiji’s transition from colonial rule to inde- Chapter 2, Child of Gujarat, is one of the most illuminating sections pendence. People who can recall the Fiji of the 1960s will have vivid of the book, describing aspects of life in Gujarat early last century which memories of Ambalal Dayhabhai Patel, Ratu Mara's resolute but not un- profoundly influenced Patel's outlook and dispositions. He was the pam- sympathetic opponent on the political stage. India-born Patel (1905-1969) pered first-born in a landed farming family of the Patidar group, the most was the leading advocate for the common franchise and the founding economically and politically powerful class in the Kheda district. -

Research Commons at The

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato http://waikato.researchgateway.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. An Elusive Dream: Multiracial Harmony in Fiji 1970 - 2000 A thesis submitted to the University of Waikato for the degree of Master of Philosophy, January, 2007. by Padmini Gaunder Abstract The common perception of Fiji, which is unique in the South Pacific, is that of an ethnically divided society with the indigenous and immigrant communities often at loggerheads. This perception was heightened by the military coups of 1987, which overthrew the democratically elected government of Dr. Timoci Bavadra because it was perceived as Indian-dominated. Again in 2000, the People’s Coalition Government headed by an Indian, Mahendra Chaudhry, was ousted in a civilian coup. Yet Fiji had been genuinely multiethnic for several decades (even centuries) before it became a colony in 1874. -

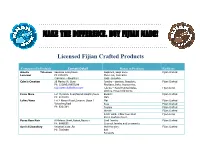

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik -

Company and Kisan

Chapter 4: Company and Kisan The relations between the Company and the growers was strong reminiscent of barons and serfs during the Middle Ages. They had to take what was given to them and be thankful for the small mercies whether they liked it or not. A.D. Patel, 1943 I am convinced that I was taking up a true and just cause and I am convinced that the stand I took and the advice I gave to the growers was right and I am proud of the part I played in that dispute. A.D. Patel, 1945 On 12 January 1938, Padri Mehar Singh, Saiyyid Latif Shah and Pandit Ajodhya Prasad went to A.D. Patel’s office in Nadi.1 They had just formed a farmers association, the Kisan Sangh, and wanted Patel to become one of its leaders. They failed to persuade Patel. According to Prasad, Patel refused to become involved. Confronting the CSR, Patel reportedly said, was like battering one’s head against the mountains of Sabeto. There was no organisation in Fiji which was strong enough to confront the Company, said Patel, and urged the three men to go home and forget about their foolish project. When Shah persisted and reminded Patel of how bad leadership and ignorance of the law had cost Indians dearly in the 1920 strike, Patel, according to Prasad, reportedly said unbelievably: ‘I’ll gladly pull the trigger if I find the government pointing its machine gun towards Indians.’ Unsuccessful in their mission, the three men left Patel’s office and went to a shady spot under a tree nearby to ponder Patel’s motives. -

Avataric Revelation and the Restoration of Spiritual Culture

AVATARIC REVELATION AND THE RESTORATION OF SPIRITUAL CULTURE: ON THE LIFE, WORK, AND PASSING OF ADI DA SAMRAJ AND THE PRESERVATION OF HIS SPIRITUAL LEGACY By Michael (Anthony) Costabile, Director Adidam Midwest Center Chicago, Illinois 773-661-0127 A paper presented at the 2009 International Conference, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA. Preliminary text, copyrighted by the author. Please do not quote without seeking the author’s written consent. NOTE: CESNUR reproduces or quotes documents from the media and different sources on a number of religious issues. Unless otherwise indicated, the opinions expressed are those of the document's author(s), not of CESNUR or its directors. 2 Avataric Revelation and the Restoration of Spiritual Culture: On the Life, Work, and Passing of Adi Da Samraj and the Preservation of His Spiritual Legacy ABSTRACT The passing of a spiritual master and the questions of succession, organizational continuity, and fidelity to the master’s life, instruction, and work have often been problematic and contentious. These challenges are not specific to any tradition and have been met variously throughout history, but they take on new dimensions in the case of Avatar Adi Da Samraj (1939-2008), the spiritual founder of Adidam Ruchiradam. The multi-tiered task of establishing a new tradition, with all of its spiritual, philosophical, aesthetic, cultural, legal, and organizational expressions is monumental in scale—like the artistic images created by Adi Da in the last decade of his life. There is an untold story in Adi Da’s work to create this new spiritual tradition and another in the maturing practice and organizational life of Adidam members—both of which have entered into a new chapter with Adi Da’s passing in November 2008. -

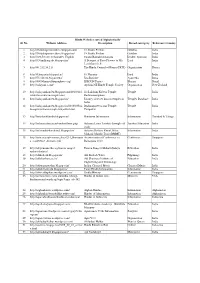

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Dilemmas of Belonging in Fiji, Part I: 5 Constitutions, Coups, and Indo

Kaplan, Martha (2018): Dilemmas of Belonging in Fiji, Part I: Constitutions, Coups, and Indo- Fijian Citizenship. In: Elfriede Hermann and Antonie Fuhse (eds.): India Beyond India: Dilem- mas of Belonging. Göttingen: Göttingen University Press (Göttingen Series in Social and Cultural Anthropology, 12), pp. 83–98. Doi: 10.17875/gup2020-1265 5 Dilemmas of Belonging in Fiji, Part I: Constitutions, Coups, and Indo-Fijian Citizenship Martha Kaplan Introduction: Towards a Historical Anthropology of Dilemmas Postcolonial nation-states and democratic electoral systems were meant to enable self-determination. Yet they have not resolved dilemmas of belonging. The Indo-Fi- jians, descendants of Indians who came to Fiji in the 19th century labor diaspora, are currently a minority in the nation-state which they share with ethnic Fijians, descen- dants of Pacific Islanders resident in the islands. This chapter describes the twentieth century history of how Indo-Fijian anticolonial spokesmen fought for independent Fiji and national belonging with a focus on ‘common roll’ electoral rights. But Fiji’s constitution at independence in 1970 was unusual for its continuation of implacable colonial race categories, its refusal of common roll, and its weighting against Indo- Fijian political representation. And then, a series of coups were mounted by ethnic Fijian military leaders, not Indo-Fijians. Many Indo-Fijians have chosen emigration when possible, seeking self-determination by diaspora. Soberly, this chapter consid- ers the history of plans for Fiji’s democracy embodied in constitutions, elections and other political rituals since 1970, the prospects for self-determination via democracy in Fiji, and the conditions for national belonging for people of Indian descent in Fiji. -

A Majority of Fiji Indians Are the Descendants of the Indentured

Pacific Dynamics: Volume 1 Number 1 July 2017 Journal of Interdisciplinary Research http://pacificdynamics.nz Indo-Fijian Counter Hegemony in Fiji: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 A historical structural approach ISSN: 2463-641X Sanjay Ramesh University of Sydney Abstract Indo-Fijians make up about 37 per cent of Fiji’s current population and have a unique language and culture, which evolved since Indians fist arrived into Fiji as indentured labourers on board the ship Leonidas in 1879. Since their arrival in the British colony as sugar plantation labourers, Indo-Fijian activists led counter hegemonic movements against the colonial government during and after indenture in 1920-21, 1943 and 1960. Indo-Fijian activists demanded political equality with Europeans and constantly agitated for better wages and living conditions through disruptive strikes and boycotts. After independence, the focus of Indo-Fijians shifted to political equality with indigenous Fijians and access to land leases from indigenous landowners on reasonable terms; and these were ongoing themes in the 1972, 1977 and 1982 elections. However, Indo-Fijian counter hegemony took a new form in 1987 with the formation of the multiracial Fiji Labour Party and National Federation Party coalition government but indigenous Fijian nationalists and the military deposed the government and established discriminatory policies against Indo-Fijians which were dismantled by the Fiji Labour Party-led coalition government in 1999. However, indigenous nationalists regrouped and deposed the government in 2000, prompting another round of protests and resistance from Indo-Fijians. Using Gramscian conceptualisation of counter hegemony as disruptive protest, resistance and dissent, I argue that political mobilisation of indentured labourers and their descendants was aimed at restoring political rights, honour, self-respect and dignity lost during colonial and post-colonial periods in Fiji. -

The Social and Religious Scene in Fiji Since the Coups

Uncertain Sequel: The Social and Religious Scene in Fiji since the Coups John Garrett Fiji's political stability since the coups of 1987 has depended partly on the interplay near the political summit between two high chiefs and a com moner. Ratu Sir Penaia Ganilau, the president of the interim government of the republic, was in April 1989 invested as Tui Cakau, the highest title in the province of Cakaudrove, within the Tovata, one ofFiji's three tradi tional confederacies. Ratu Sir Kamisese Mara, the interim prime minister, is the bearer of the high titles Tui Nayau and Tui Lau in the same confed eracy. His authority extends over both southern and northern Lau-the eastern islands of the Fiji group (see Garrett 1988). Major-General Sitiveni Rabuka, the soldier-commoner, does not have the hereditary power of the other two members of the triumvirate. A professional warrior, he is largely a self-made man (Dean and Ritova 1988). He acquired his present power by dissolving a constituted Parliament at the head of troops schooled in abrupt intervention in the Fiji Battalion of the United Nations International Peacekeeping Force in south Lebanon. His troops have seen Israeli units in action. THE PARADOX OF RABUKA Ratu Ganilau and Ratu Mara conform to the pyramidal Polynesian struc tures and mores of ethnic Fijian society. Rabuka, through his upbringing, works within the same framework. He affirms the loyalty and customary duty he owes to high chiefs within a rank-order determined by birth. His activity in the two coups, and as minister for home affairs and commander The Contemporary Pacific, Volume 2, Number I, Spring 1990, 87-II1 © 1990 by University ofHawaii Press 88 THE CONTEMPORARY PACIFIC· SPRING I990 of the security forces since, presents a paradox. -

Introduction

Introduction ‘Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,’ AD Patel quoted William Wordsworth’s celebration of the French Revolution as he launched the 1966 election campaign at the Century Theatre in Suva, ‘but to be young was very heaven.’ He was unwell, an acute, insulin-dependent diabetic now also suffering from pneumonia. His mother’s recent death in India would have added to his emotional woes. ‘My voice has failed me today,’ he told his anxious audience long concerned about his failing health. But he was undaunted. ‘Mine is the fortune of being alive in this dawn. Mine is the misfortune that I won’t be able to share the very heaven.’ His premonition of impending mortality sadly proved accurate. Three years later, on 1 October 1969, he died of a massive heart attack at his home in Nadi, almost exactly a year before Fiji became independent from the United Kingdom after ninety-six years of colonial rule. ‘AD was a fine man stubborn, sometimes too much so for comfort,’ wrote QVL Weston on 24 October 1969, ‘but it was through his stubbornness that he got his way, and I think when the tale is told by the historians, it will usually be accepted that his way was right.’ Now the Chief Secretary of Nauru, he had been Commissioner Western based at Lautoka in the early 1960s, witnessing at first hand as the Government’s chief civilian administrator in the sugar belt of Fiji, the first stirrings of political change as Fiji moved haphazardly towards internal self-government and eventually independence. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

AD Patel and the Politics of Fiji

for A Vision Change AD Patel and the Politics of Fiji for A Vision Change AD Patel and the Politics of Fiji Brij V Lal THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E PRESS E PRESS Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Lal, Brij V. Title: A vision for change : A.D. Patel and the politics of Fiji / Brij V Lal. ISBN: 9781921666582 (pbk.) ISBN: 9781921666599 (ebook) Subjects: Patel, A. D. |q (Ambalal Dahyabhai), 1905-1969. Fiji--Politics and government--20th century. Fiji--History. Dewey Number: 320.099611 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2011 ANU E Press Contents Preface to this Edition . .vii Prologue . ix Chapter 1: Retrospect . 1 Chapter 2: Child of Gujarat . 17 Chapter 3: Into the Fray . 35 Chapter 4: Company and Kisan . 57 Chapter 5: Flesh on the Skeleton . 81 Chapter 6: Interregnum . 105 Chapter 7: Fire in the Cane Fields . 129 Chapter 8: Towards Freedom . 157 Chapter 9: Shaking the Foundations . 183 Chapter 10: Independence Now . 213 Chapter 11: The End in Harness . 241 References . 251 Appendix: Telling the Life of A .D . Patel . 255 Index . 273 v Preface to this Edition This book was first published in 1997 after nearly a decade of interrupted research going back to the early 1980s.