Rail for All – Developing a Vision for Railway Investment in Scotland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download 1212.Pdf

CLACKMANNANSHIRE COUNCIL STIRLING - ALLOA - KINCARDINE RAILWAY (ROUTE RE- OPENING) AND LINKED IMPROVEMENTS (SCOTLAND) BILL ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT VOLUME 3 SUPPORTING INFORMATION FEBRUARY 2003 Scott Wilson (Scotland) Ltd Contact: Nigel Hackett 23 Chester Street Edinburgh EH3 7ET Approved for Issue: Tel: 0131 225 1230 Name: N Hackett Fax: 0131 225 5582 Ref: B109401ENV1 Date: 14/02/03 CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................................1 2. CULTURAL HERITAGE.....................................................................................................11 3. AIR QUALITY.......................................................................................................................70 4. LANDSCAPE AND VISUAL EFFECTS.............................................................................94 5. ECOLOGY ...........................................................................................................................118 6. NOISE AND VIBRATION..................................................................................................133 7 WATER RESOURCES.......................................................................................................194 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background This document relates to the Stirling–Alloa–Kincardine Railway (Route Re-opening) and Linked Improvements (Scotland) Bill introduced in the Scottish Parliament on 27 March 2003 (to be confirmed). It has been prepared by Scott Wilson Scotland -

Cornwall's New Aberdeen Directory

M. 7£ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/cornwallsnewaber185354abe CORNWALL^ NEW ABERDEEN DIRECTORY, 1853 54; COMPRISING A NEW GENERAL DIRECTORY; NEW TRADES' AND PROFESSIONS' DIRECTORY; NEW STREET DIRECTORY; NEW COTTAGE, VILLA, & SUBURBAN DIRECTORY; NEW PUBLIC INSTITUTIONS DIRECTORY; NEW COUNTY DIRECTORY; ETC. ETC. ETC. ABERDEEN: GEO. CORNWALL, 54, CASTLE STREET. 1853. ft? *•£*.••• > £ NOTE BY THE PUBLISHER. It is due to the Public to state that, in order to procure informa- tion for the " City " portion of this Directory, from Five to Six Thousand Schedules were issued, for the purpose of being filled up by the Inhabitants. In transcribing these Schedules, the utmost care was taken to preserve the exact address and orthography of Name which had been given; and, still farther to preserve the accuracy of the Work, the ' whole of the Names, after they had been put into type, were again, at a large sacrifice of time, care- fully compared, one by one, with the original Schedules. The " County " Directory, which forms an important part of the Work, has been made up from returns furnished, in almost every instance, by the Schoolmasters of the respective Parishes. To the Gentlemen who have thus so kindly assisted him, the Publisher gladly embraces the present opportunity of returning his most grateful thanks. The short delay which has occurred in getting the Work issued, has been as much a disappointment to the Publisher as it can have been to his Subscribers. To those of them, however, who may have been incommoded by the delay, he begs to offer a respectful apology, and to assure them that, from the complicated and laborious nature of the Work, (this Directory being an entirely new compilation), the delay was found to be quite un- avoidable. -

Borders Railway Timetable

11601 ScotRail is part of the Published by (Textphone Service – for the hard of hearing) 18001 0800 2 901 912 OR 0800 2 901 912 Disabled Assistance [email protected] 0344 0141 811 can contact Customer Relations on: general enquiries, telesales you all including For www.scotrail.co.uk ScotRail (please note, calls to this number may be recorded) 08457 48 50 49 EnquiriesNational Rail Abellio ScotRail Ltd. ScotRail Abellio National Rail network ES M I T N I ideann – Talla na Creige Nuadh – Bruach Thuaidh È A n R ù Calling at: Brunstane Shawfair Eskbank Newtongrange Gorebridge Stow & Galashiels Includes through trains to Tweedbank from 6 September T 17 May to 12 December 2015 Edinburgh – Newcraighall – – Newcraighall Edinburgh Tweedbank D Welcome to your new train timetable Station Facilities All trains in this timetable are ScotRail services operated by Abellio, except where otherwise Brunstane U shown. We aim to make your train journey as easy as possible and are continuing to improve Edinburgh * S services across the Network. In the West Highlands the first Glasgow to/from Oban train will Eskbank U now run additionally on Saturdays. Seven new stations will open in the Scottish Borders Galashiels U from 6 September with Edinburgh to Newcraighall trains extended to Tweedbank. This will Gorebridge U also include an hourly Sunday service throughout the day. From 17 May a similar Sunday Newcraighall * U service will be introduced from Edinburgh to Newcraighall and an hourly Sunday service will Newtongrange U commence between Glasgow and Paisley Canal. Duke Street, Alexandra Parade and Barnhill Stow U stations will also benefit from a Sunday service with trains running hourly between Partick and Shawfair U Cumbernauld. -

Dundee Harbour Line

Angus Railway Group JOU No 155 SUMMER 2001 ERROL STATION (ALMOST) SOLD We are reliably informed that after many months and several interested parties, Errol Station is at last about to be sold. It would appear that only a minor formality with the bank involved. needs to be clarified and the sale can go ahead. This has been quite a fraught saga for those immediately involved, but it ,I would seem that their efforts are about to be repaid. i 'CARMYLLIE PILOT' TO STEAM iAGAIN? [ Tayside's much loved but greatly neglected asset, the Ivatt 2-6-0, No 46464, may yet be returned to steam. A newly formed group has been set up to over- see the work on the not so old lady, who has just turned 50. David Fraser, the son of the late Ian Fraser, who purchased the locomotive from BR in the mid The southern spans of therr.. arch viaduct which car- sixties, has agreed to handing over part ownership to ried the Dundee and Forfar Direct Railway over the the new group. Work is estimated to cost £40,000 and Dighty Water at Barnhill. This view looking to the north, is expected to take five years. was taken in June 1973. (photograph, Jim Page.) L ~ ~ ~ I- IBROUGHTY FERRY REFURBISHMENT IS UNDERWAY - AT LAST! ! Work has finally started on the restoration of the station, and is expected to take 26 weeks. At the Itime of writing, part of the canopy over the southbound platform has been removed along with the roof I of the signal box. -

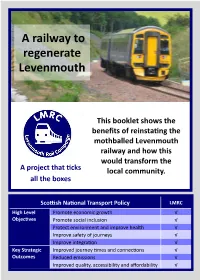

A Railway to Regenerate Levenmouth

A railway to regenerate Levenmouth This booklet shows the benefits of reinstating the mothballed Levenmouth railway and how this would transform the A project that ticks local community. all the boxes Scottish National Transport Policy LMRC High Level Promote economic growth √ Objectives Promote social inclusion √ Protect environment and improve health √ Improve safety of journeys √ Improve integration √ Key Strategic Improved journey times and connections √ Outcomes Reduced emissions √ Improved quality, accessibility and affordability √ CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Executive Summary 1 1.2 The Vision 2 1.3 The Proposal 3 2. BACKGROUND INFORMATION 2.1 The mothballed Leven line 4 2.2 Population 6 2.3 Previous studies 8 2.4 Potential rail freight 10 2.5 Support for Levenmouth rail link 11 3. BENEFITS 3.1 Personal stories 12 3.2 What makes a good rail reopening project? 14 3.3 Delivering Scottish Government policy 15 3.4 Freight 16 3.5 Land Value Capture 17 3.6 Tourism 18 3.7 Wider economic and regional benefits 20 3.8 The business case - Benefit to Cost ratio 21 4. RE-INSTATING THE RAILWAY 4.1 Construction costs - Comparing Levenmouth with Borders 22 4.2 Timetable issues 24 4.3 Other project issues 25 5. MOVING FORWARD 5.1 Conclusions 26 5.2 The final report? 26 6. LEVENMOUTH RAIL CAMPAIGN 6.1 About our campaign 27 6.2 Our Charter 28 6.3 More information 29 - 1 - 1. Introduction 1.1 Executive Summary This booklet has been produced by the Levenmouth Rail Campaign (LMRC) with the support of a group of railway professionals who wish to lend their expertise to the campaign. -

Flying Into the Future Infrastructure for Business 2012 #4 Flying Into the Future

Infrastructure for Business Flying into the Future Infrastructure for Business 2012 #4 Flying into the Future Flying into the Future têáííÉå=Äó=`çêáå=q~óäçêI=pÉåáçê=bÅçåçãáÅ=^ÇîáëÉê=~í=íÜÉ=fça aÉÅÉãÄÉê=OMNO P Infrastructure for Business 2012 #4 Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ________________________________________ 5 1. GRowInG AVIATIon SUSTAInABlY ______________________ 27 2. ThE FoUR CRUnChES ______________________________ 35 3. ThE BUSInESS VIEw oF AIRpoRT CApACITY ______________ 55 4. A lonG-TERM plAn FoR GRowTh ____________________ 69 Q Flying into the Future Executive summary l Aviation provides significant benefits to the economy, and as the high growth markets continue to power ahead, flying will become even more important. “A holistic plan is nearly two thirds of IoD members think that direct flights to the high growth countries will be important to their own business over the next decade. needed to improve l Aviation is bad for the global and local environment, but quieter and cleaner aviation in the UK. ” aircraft and improved operational and ground procedures can allow aviation to grow in a sustainable way. l The UK faces four related crunches – hub capacity now; overall capacity in the South East by 2030; excessive taxation; and an unwelcoming visa and border set-up – reducing the UK’s connectivity and making it more difficult and more expensive to get here. l This report sets out a holistic aviation plan, with 25 recommendations to address six key areas: − Making the best use of existing capacity in the short term; − Making decisions about where new runways should be built as soon as possible, so they can open in the medium term; − Ensuring good surface access and integration with the wider transport network, in particular planning rail services together with airport capacity, not separately; − Dealing with noise and other local environment impacts; − Not raising taxes any further; − Improving the visa regime and operations at the UK border. -

Investing for the Future

The new ScotRail franchise: good for passengers, staff and Scotland Improving your journey from door to door magazine Abellio ScotRail Investing for the future The Abellio Way Magazine – Abellio ScotRail special – Spring 2015 Travelling on the Forth Bridge and enjoying the wonderful view A northern gannet flying in front of Bass Rock SCOTRAIL SPECIAL - SPRING 2015 3 CONTENTS Ambitious plans and Abellio It is with enormous pleasure that I find myself writing 4 WE ARE ABELLIO the introduction to this special edition of The Abellio What can you expect from us? Way Magazine from my home in Edinburgh. When Abellio was granted the privilege of operating 6 JEFF HOOGESTEGER MEETS TRANSPORT Scotland’s rail services, I had no hesitation in making this my home. You may consider that a rather self- MINISTER DEREK MACKAY serving decision, after all who wouldn’t choose to live “This is an incredibly exciting period for transport in this beautiful country! However, as a Dutchman, it in Scotland” won’t surprise you that it was also a sensible business decision. 10 ABELLIO’S VISION FOR THE NEW The Scottish Government has ambitious plans to SCOTRAIL FRANCHISE transform its railways and I am grateful to them for Good for passengers, good for staff and choosing Abellio to assist in that purpose. We have many exciting and challenging plans for ScotRail, as good for Scotland you will read in this special edition, and it is my intention to work with the team wherever possible 13 WORKING TOGETHER FOR THE PASSENGER to deliver them. ScotRail and Network Rail Performance for passengers 14 BOOSTING TOURISM Living here, I will also be travelling by train most days to our new UK headquarters in Glasgow, and regularly Travel the Great Scenic Railways of Scotland using other parts of the ScotRail network. -

The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report

The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report January 2003 Ove Arup & Partners International Ltd Admiral House, Rose Wharf, 78 East Street, Leeds LS9 8EE Tel +44 (0)113 242 8498 Fax +44 (0)113 242 8573 REP/FI Job number 68772 The City of Edinburgh Council Edinburgh LRT Masterplan Feasibility Study Final Report CONTENTS Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. INTRODUCTION 9 1.1 Scope of the Report 9 1.2 Study Background and Objectives 9 1.3 Transport Trends 10 1.4 Planning Context 10 1.5 The Integrated Transport Initiative 11 1.6 Study Approach 13 1.7 Light Rapid Transit Systems 13 2. PHASE 1 APPRAISAL 18 2.1 Introduction 18 2.2 Corridor Review 18 2.3 Development Proposals 21 2.4 The City of Edinburgh Conceptual Network 22 2.5 Priorities for Testing 23 2.6 North Edinburgh Loop 24 2.7 South Suburban Line 26 2.8 Appraisal of Long List of Corridor Schemes 29 2.9 Phase 1 Findings 47 3. APPROACH TO PHASE 2 50 3.1 Introduction 50 3.2 Technical Issues and Costs 50 3.3 Rolling Stock 54 3.4 Tram Services, Run Times and Operating Costs 55 3.5 Environmental Impact 55 3.6 Demand Forecasting 56 3.7 Appraisal 61 4. NORTH EDINBURGH LOOP 63 4.1 Alignment and Engineering Issues 63 4.2 Demand and Revenue 65 4.3 Environmental Issues 66 4.4 Integration 67 4.5 Tram Operations and Car Requirements 67 4.6 Costs 68 4.7 Appraisal 69 5. -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

Railfuture Scotland News Issue 67

SCOTTISH BRANCH NOTES No 67: March 2009 Spring Meeting & AGM Sat 21st March at 14:00 Railfuture Scotland Press Release Railfuture Scotland has submitted a five point strategy to Transport in Royal Over-Seas League, 100 Princes St., Edinburgh Scotland outlining five new strategies to encourage greater use of Scotland’s publicly supported rail network. Topic : Rail Development Projects in Scotland (1) Last minute ‘turn up and fill up’ otherwise empty seats at bargain fares, as a pilot scheme on selected longer distance trains currently leaving with ‘empty seats’. Programme: (2) Removing the unnecessary and unfair ticket 09.15 ticket restric- tion applied in remoter areas with very infrequent services and long • Talk - speaker from Transport Scotland distances to major population centres in central Scotland. • Questions to the speaker (3) Ending the perverse fare discrimination against single journey • Coffee/Tea break rail tickets which only serves to discourage use of rail travel in many situations. • Branch AGM - a chance for members to vote for office-bearers, (4) Removing the peculiar and irrational discrimination against those ask questions, and to provide guidance to the Committee for who don’t return by train the same day. policy and activity for the future (5) Extending the National Concession Travel Scheme to include rail ROSL: Just west of Frederick Street junction with Princes St. travel as an alternative to the current bus-only travel scheme. Full details of those proposals have been submitted to Transport Editorial Scotland as part of the Consultation Document on the ScotRail’s Franchise Extension from 2011 to 2014. Its Consultation Question It’s been quite a busy period since the last issue of Branch Notes. -

Junction 2 M80 Glasgow Junction 2 M80 Glasgow

Junction 2 M80 Glasgow Junction 2 M80 Glasgow Rowan House. Good quality open plan accommodation www.novabusinesspark.com Location Nova Business Park is located 5 miles to the north east of Glasgow city M80 Robroyston centre, accessed immediately off Junction 2 of the M80 motorway. This Retail Park A803 provides excellent access to the main motorway network of Scotland via the M80, M8, M73 and M74. 2 Robroyston A80 Barnhill railway station is approximately 2 miles away providing access to Park the city centre. Lenzie railway station is 3 miles away, which provides a direct link to Edinburgh. M80 Petershill Park Barnhill Robroyston Retail Park is immediately adjacent to the site providing an Station 1 ASDA superstore, McDonald’s restaurant and Homebase. In addition, Cumbernauld Road Lethamhill Greene King will be opening a restaurant on site in 2014 12 Golf Course . 12 Springburn Road A803 A80 13 M8 Edinburgh Glasgow Accommodation 15 Alexandra City Centre Golf Course 14 M8 Floor Sq M Sq Ft Cumbernauld Road Second 1,268.3 13,652 First 1,267.8 13,646 Ground 1,233.6 13,278 Total* 3,769.7 40,576 *Suites from 6,628 sq ft available. Building Specification • Double height entrance • Secure door entry system Typical Floor Plate • CCTV • Open plan and cellular accommodation • 24 hour access • Suspended ceiling with integrated Cat 2 lighting • High quality reception area • Comfort cooling • 2 x Passenger lifts • Male, female and ambulant toilets WCs • DDA compliant • Kitchen / fitted canteen area LIFT LIFT WCs Terms Viewing and The property is available to Further Information lease. -

Rail for All Report

RAIL FOR ALL Delivering a modern, zero-carbon rail network in Scotland Green GroupofMSPs Policy Briefing SUMMARY Photo: Times, CC BY-SA 2.5 BY-SA Times, CC Photo: The Scottish Greens are proposing the Rail for All investment programme: a 20 year, £22bn investment in Scotland’s railways to build a modern, zero-carbon network that is affordable and accessible to all and that makes rail the natural choice for commuters, business and leisure travellers. This investment should be a central component of Scotland’s green recovery from Covid, creating thousands of jobs whilst delivering infrastructure that is essential to tackle the climate emergency, that supports our long-term economic prosperity, and that will be enjoyed by generations to come. CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE 1 Creating the delivery infrastructure 4 i. Steamline decision-making processes and rebalance 4 them in favour of rail ii. Create one publicly-owned operator 4 iii. Make a strategic decision to deliver a modern, 5 zero-carbon rail network and align behind this iv. Establish a task force to plan and steer the expansion 5 and improvement of the rail network 2 Inter-city services 6 3 Regional services 9 4 Rural routes and rolling stock replacement 10 5 TramTrains for commuters and urban connectivity 12 6 New passenger stations 13 7 Reopening passenger services on freight lines 14 8 Shifting freight on to rail 15 9 Zero-carbon rail 16 10 Rail for All costs 17 11 A green recovery from Covid 18 This briefing is based on the report Rail for All – developing a vision for railway investment in Scotland by Deltix Transport Consulting that was prepared for John Finnie MSP.