Università Di Pisa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Libya Conflict Insight | Feb 2018 | Vol

ABOUT THE REPORT The purpose of this report is to provide analysis and Libya Conflict recommendations to assist the African Union (AU), Regional Economic Communities (RECs), Member States and Development Partners in decision making and in the implementation of peace and security- related instruments. Insight CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Mesfin Gebremichael (Editor in Chief) Mr. Alagaw Ababu Kifle Ms. Alem Kidane Mr. Hervé Wendyam Ms. Mahlet Fitiwi Ms. Zaharau S. Shariff Situation analysis EDITING, DESIGN & LAYOUT Libya achieved independence from United Nations (UN) trusteeship in 1951 Michelle Mendi Muita (Editor) as an amalgamation of three former Ottoman provinces, Tripolitania, Mikias Yitbarek (Design & Layout) Cyrenaica and Fezzan under the rule of King Mohammed Idris. In 1969, King Idris was deposed in a coup staged by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi. He promptly abolished the monarchy, revoked the constitution, and © 2018 Institute for Peace and Security Studies, established the Libya Arab Republic. By 1977, the Republic was transformed Addis Ababa University. All rights reserved. into the leftist-leaning Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya. In the 1970s and 1980s, Libya pursued a “deviant foreign policy”, epitomized February 2018 | Vol. 1 by its radical belligerence towards the West and its endorsement of anti- imperialism. In the late 1990s, Libya began to re-normalize its relations with the West, a development that gradually led to its rehabilitation from the CONTENTS status of a pariah, or a “rogue state.” As part of its rapprochement with the Situation analysis 1 West, Libya abandoned its nuclear weapons programme in 2003, resulting Causes of the conflict 2 in the lifting of UN sanctions. -

Libya's Growing Risk of Civil War | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 2256 Libya's Growing Risk of Civil War by Andrew Engel May 20, 2014 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Andrew Engel Andrew Engel, a former research assistant at The Washington Institute, recently received his master's degree in security studies at Georgetown University and currently works as an Africa analyst. Brief Analysis Long-simmering tensions between non-Islamist and Islamist forces have boiled over into military actions centered around Benghazi and Tripoli, entrenching the country's rival alliances and bringing them ever closer to civil war. n May 16, former Libyan army general Khalifa Haftar launched "Operation Dignity of Libya" in Benghazi, O aiming to "c leanse the city of terrorists." The move came three months after he announced the overthrow of the government but failed to act on his proclamation. Since Friday, however, army units loyal to Haftar have actively defied armed forces chief of staff Maj. Gen. Salem al-Obeidi, who called the operation "a coup." And on Monday, sympathetic forces based in Zintan extended the operation to Tripoli. These and other developments are edging the country closer to civil war, complicating U.S. efforts to stabilize post-Qadhafi Libya. DIVIDING LINES I slamists and non-Islamist forces have long been contesting each other's claims to being the legitimate heart of the 2011 revolution. Islamist factions such as the Muslim Brotherhood-related Justice and Construction Party and the Loyalty to the Martyrs Bloc have dominated the General National Congress (GNC) since summer 2013, when the forcibly passed Political Isolation Law effectively barred all former Qadhafi regime members -- even those who had fought the regime -- from participating in government for ten years. -

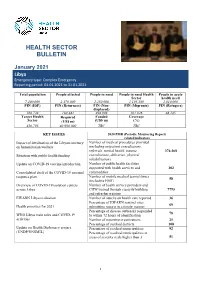

January 2021 Libya Emergency Type: Complex Emergency Reporting Period: 01.01.2021 to 31.01.2021

HEALTH SECTOR BULLETIN January 2021 Libya Emergency type: Complex Emergency Reporting period: 01.01.2021 to 31.01.2021 Total population People affected People in need People in need Health People in acute Sector health need 7,400,000 2,470,000 1,250,000 1,195,389 1,010,000 PIN (IDP) PIN (Returnees) PIN (Non- PIN (Migrants) PIN (Refugees) displaced) 168,728 180,482 498,908 301,026 46,245 Target Health Required Funded Coverage Sector (US$ m) (US$ m) (%) 450,795 40,990,000 TBC TBC KEY ISSUES 2020 PMR (Periodic Monitoring Report) related indicators Impact of devaluation of the Libyan currency Number of medical procedures provided on humanitarian workers (including outpatient consultations, referrals, mental health, trauma 376.468 Situation with public health funding consultations, deliveries, physical rehabilitation) Update on COVID-19 vaccine introduction Number of public health facilities supported with health services and 302 Consolidated draft of the COVID-19 national commodities response plan. Number of mobile medical teams/clinics 58 (including EMT) Overview of COVID-19 isolation centers Number of health service providers and across Libya CHW trained through capacity building 7793 and refresher training EWARN Libya evaluation Number of attacks on health care reported 36 Percentage of EWARN sentinel sites 68 Health priorities for 2021 submitting reports in a timely manner Percentage of disease outbreaks responded 78 WHO Libya main roles and COVID-19 to within 72 hours of identification activities Number of reporting organizations 25 Percentage of reached districts 100 Update on Health Diplomacy project Percentage of reached municipalities 92 (UNDP/UNSMIL) Percentage of reached municipalities in areas of severity scale higher than 3 51 1 HEALTH SECTOR BULLETIN January 2021 SITUATION OVERVIEW • The UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called on foreign fighters and mercenaries in Libya to immediately leave because "the Libyans have already proven that, left alone, they are able to address their problems". -

Dissenting Opinion of Judge Sette-Camara

DISSENTING OPINION OF JUDGE SETTE-CAMARA 1 regret that 1 have been unable to agree with the Court's majority in the present Judgment in its appraisal of the facts, in its reasoning and in its conclusions, and therefore feel under the obligation to explain why 1 see this case differently. The disputed zone is the so-called Libya-Chad borderlands, bounded to the north-east by the east-south-east line of the Anglo-French Conven- tion of 8 September 1919, to the south by the 15" north latitude parallel, to the West by the 24" E meridian and to the east by the 16" E meridian. It covers an area of some 530,000 km' and encompasses the Borkou- Ounianga, the Ennedi and the Tibesti, what Chad refers to as the BET (excluding northern Kanem). The population of the area is under 100,000, compared with Chad's population of some 5.4 million, including the BET. The area contains 2 per cent of Chadian local population and it is a poor, bare and inhospitable region. In spite of the desertic nature of this zone, that we shall for conven- terra nullius. ience continue to cal1 the borderlands. it was never a , ouen. to occupation according to international law. The two Parties concur as to that, and echo herein the analogous finding of the Court in the Western Sahara case. The land was occupied by local indigenous tribes, confed- erations of tribes, often organized under the Senoussi Order. Further- more, it was under the distant and laxly exercised sovereignty of the Ottoman Empire, which marked its presence by delegation of authority to local people. -

Crisis Committee

CRISIS COMMITTEE Lyon Model United Nations 2018 Study Guide Libyan Civil War !1 LyonMUN 2018 – Libyan Civil War Director: Thomas Ron Deputy Director: Malte Westphal Chairs: Laurence Turner and Carine Karaki Backroom: Ben Bolton, Camille Saikali, Margaux Da Silva, and Antoine Gaudim !2 Director’s Welcome Dear Delegates, On behalf of the whole team I would like to welcome you to LyonMUN 2018 and this simulation of the Libyan Civil War. It is strange to feel that such an important topic that we all remember happening is already over 7 years old. Therefore, we felt it would be a good time to simulate it and think about the ways it could have gone. As delegates you will each be given characters to play in this crisis. These were real people who made a difference within the actual Civil War and have their own objectives and goals. You are tasked with advancing the goals of your character and making sure that they end up doing well out of this crisis. Every action will have consequences, everything you do will have ramifications, and mistakes can be deadly. Your chairs will be there to help but they will also be representing characters and have their own interests, meaning they may not be fully trustworthy. Behind the scenes you will have a backroom which will interpret your directives and move the plot forward. We will be there to read what you say and put it into action. However, a word to the wise, the way your wish may be interpreted may not be ideal. -

Minority Ethnic Groups

Country Information and Guidance Libya: Minority ethnic groups 18 February 2015 Preface This document provides guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling claims made by nationals/residents of - as well as country of origin information (COI) about - Libya. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the guidance contained with this document; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Within this instruction, links to specific guidance are those on the Home Office’s internal system. Public versions of these documents are available at https://www.gov.uk/immigration- operational-guidance/asylum-policy. Country Information The COI within this document has been compiled from a wide range of external information sources (usually) published in English. Consideration has been given to the relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability of the information and wherever possible attempts have been made to corroborate the information used across independent sources, to ensure accuracy. All sources cited have been referenced in footnotes. It has been researched and presented with reference to the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI), dated April 2008, and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, dated July 2012. -

Security Council Provisional Asdfsixty-Ninth Year 7194Th Meeting Monday, 9 June 2014, 10.10 A.M

United Nations S/ PV.7194 Security Council Provisional asdfSixty-ninth year 7194th meeting Monday, 9 June 2014, 10.10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Churkin ..................................... (Russian Federation) Members: Argentina ....................................... Mrs. Perceval Australia ........................................ Mr. White Chad ........................................... Mr. Cherif Chile ........................................... Mr. Llanos China .......................................... Mr. Shen Bo France .......................................... Mr. Araud Jordan .......................................... Mr. Hmoud Lithuania ........................................ Mr. Kalindra Luxembourg ..................................... Ms. Lucas Nigeria ......................................... Mr. Laro Republic of Korea ................................. Ms. Paik Ji-ah Rwanda ......................................... Mr. Gasana United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland .... Sir Mark Lyall Grant United States of America ........................... Mrs. DiCarlo Agenda The situation in Libya This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the translation of speeches delivered in other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of a member of the delegation concerned to the Chief of the Verbatim Reporting -

1/7 November 2014 UNHCR POSITION ON

November 2014 UNHCR POSITION ON RETURNS TO LIBYA Introduction 1. Since the overthrow of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and his government in October 2011, Libya has been affected by a chronic state of insecurity.1 In a climate of instability and chaos, the country has seen intense clashes between armed groups and almost daily assassinations, bombings and kidnappings. The presence of numerous militias – some reports indicate that there are up to 1,700 different armed groups2 – each reported to control certain areas of territory, have left successive governments struggling to exercise authority in those areas. The many armed groups are reported to be ideologically divided and are said to be split along geographical lines in the country. Analysts have expressed concerns about the risk of Libya descending into civil war.3 Intense fighting between rival armed groups takes its toll on civilians, as hundreds of thousands have been forcibly displaced across the country, vital infrastructure has been destroyed and the humanitarian situation is rapidly deteriorating.4 Recent Political Developments (2014) 2. Social unrest, evidenced, inter alia, by demonstrations, armed clashes, and an increase in kidnappings and killings has been reported in Libya in a climate of deteriorating security. Since January 2014, Libya has had rapid succession in the Executive branch that is closely linked to the increasingly divided political landscape. In February 2014, protests erupted when the parliament, the General National Congress (GNC), cited the need for drafting a new constitution and extended its mandate beyond 7 February 2014. On 16 May 2014, the situation further deteriorated when a former General, Khalifa Haftar,5 launched a military offensive against armed groups in Benghazi. -

Anupropaz A2016.Pdf

Impresión: Diseño: Lucas J. Wainer ISBN: Depósito Legal: B-14.344.2008 Este anuario ha sido elaborado por Vicenç Fisas, director de la Escola de Cultura de Pau de la UAB. El autor agradece la información facilitada por varias personas del equipo de investigación de la Escola, particularmente Ana Ballesteros, Iván Navarro, Josep Maria Royo, Jordi Urgell, Pamela Urrutia, Ana Villellas y María Villellas. Vicenç Fisas es también doctor en estudios sobre paz por la Universidad de Bradford, premio Nacional de Derechos Humanos 1988 y autor de más de treinta libros sobre conflictos, desarme, investigación sobre la paz o procesos depaz. Algunos de los títulos publicados son: Diplomacias de paz: negociar con grupos armados; Manual de procesos de paz; Procesos de paz y negociación en conflictos armados; La paz es posible; y Cultura de paz y gestión de conflictos. Índice Glosario 7 Europa 195 a) Sudeste de Europa 195 Presentación: definiciones y tipologías 13 Chipre 195 Kosovo 201 Fases habituales en los procesos de Moldova (Transdniestria) 208 negociación 15 Turquía (PKK) 213 Ucrania 223 Principales conclusiones del año 19 b) Cáucaso 233 Armenia-Azerbaiyán 233 Los procesos de paz en 2015 26 Georgia (Abjasia y Osetia del Sur) 238 Los conflictos y los procesos de paz al Oriente Medio 245 finalizar 2015 27 Israel-Palestina 245 Los conflictos y los procesos de paz de los últimos años 31 Análisis por países Anexos África 31 1. Procesos analizados en los capítulos a) África Occidental 31 de los anuarios, de 2006 a 2016. 253 Malí (Tuaregs) 31 Senegal (Casamance) 38 2. Acuerdos de paz y ratificación del Estatuto b) Cuerno de África 42 de Roma de la Corte Penal Internacional. -

Libyan Unrest Will Force Oil Prices Higher

Libyan unrest will force oil prices higher Industrialized countries may be faced with the prospect of a shrinking oil supply and higher prices in the second half of the year unless a solution is found to increase production due to higher than expected demand. OPEC controls about 40% of world oil reserves and includes members such as Libya and Iraq, which have struggled to maintain their export output due to severe domestic instability and intensifiying political unrest in some non-OPEC countries such as Colombia and South Sudan, not to mention the tensions between Russia and Ukraine that had already served to raise oil prices in recent weeks. Chinese demand, despite rumors of a slowing economy, is having a significant impact on demand as imports have reached record levels of 6.8 million barrels a day (bpd) last April. China has actually been increasing strategic oil reserves and refining capacity as two new giant facilities have been built. Brent crude actually shot up to above USD$ 109 in London in response to the rising uncertainty in Libya, where crude oil production has fallen to about 210,000 barrels per day, well below the pre-crisis levels of 1.4 million barrels, with the deposits of the western regions that remain idle. The resumption of heavy fighting using artillery and aircraft around the area of Benghazi is to blame. Indeed, the exacerbation of Libyan unrest and the prospect of a potential return of military dictatorship have effectively eroded any hope that the post-Qadhafi government, might yet survive much longer. The Libyan situation is made all the worse by the fact that the clashes in Tripoli and Benghazi have been far more complex than simply those between the good – non- Islamists – and the bad – the Islamists. -

Libya: Who's Fighting Whom and Why?

Libya: Who's Fighting Whom and Why? Over the last few days, competing militias have clashed in Benghazi and Tripoli underlining the deep tensions within the General National Congress. ARTICLE | 21 MAY 2014 - 4:08PM | BY RED24 On 16 May, the retired Libyan army general Khalifa Belqasim Haftar along with the self-styled Libyan National Army (LNA) embarked on Operation Dignity. The military campaign targeted Islamist militia − including Ansar al-Sharia (AS), Rafallah al-Sahati and the February 17 Brigade − in the eastern Libyan city of Benghazi. Haftar's forces included Khalifa Belqasim Haftar, the general at the heart of the current conflict. Photograph by Magharebia. approximately 6,000 soldiers, supporting aircraft and heavy weaponry, and focused on the al-Quwarsha, Sidi Faraj and al-Hawari areas of the city. By 17 May, at least 79 people had been killed and dozens more wounded. Haftar's forces later withdrew from the city. Haftar's Benghazi assault also sparked an attack by some Zintan-based militia groups − the al-Qaaqaa, al- Madani, and Sawaaq − on the General National Congress (GNC) in Tripoli on 18 May. This assault included an attack on the Public Officials Standards Commission (POSC) facility, an office tasked with enforcing the Political Isolation Law, a controversial piece of legislation that aims to block former regime officials from standing for office. The militias also abducted ten POSC personnel. Clashes between these militia forces and Islamist militia further occurred across Tripoli and left at least five people dead. The fighting occurred in the Abu Salim, Bab Ben Ghashir and Suq al-Juma areas, between the Defence Ministry-aligned Zintani militia, and forces from the Interior Ministry-aligned Islamist Libyan Revolutionaries Operating Room (LROR) and Islamist Special Deterrent Force. -

How Sirte Became a Hotbed of the Libyan Conflict Sirte: a New Frontline (June 2020) Cover

How Sirte Became a Hotbed of Issue 2021/05 the Libyan Conflict February 2021 Omar Al-Hawari1 Abstract The birthplace and former stronghold of the late Muammar Qadhafi, the coastal city of Sirte, was stigmatised and marginalised following the fall of the regime in October 2011. However, since 2019 it has again become the epicentre of Libya’s domestic and international conflict. How can this sudden change in the strategic importance of the city be explained? Based on numerous interviews with key actors from Sirte and on both warring sides, this paper analyses how the strategic importance of Sirte has evolved since Haftar’s LAAF military offensive on Tripoli in April 2019 and how the city has now become central to the Libyan conflict and its resolution through international diplomatic efforts. Introduction The city of Sirte, located in the middle of the Libyan littoral and at the western edge of the ‘Oil Crescent,’ was the theatre of the final battle of the 2011 civil war, but after being ‘liberated’ by the revolutionary forces in October it faded into the margins of Libya’s transition. The city was military defeated, socially marginalised and politically excluded. However, since 2019 it has again become the epicentre of Libya’s domestic and international conflict. How can this sudden BRIEF change in the strategic importance of the city be explained? The birthplace and former stronghold of the late Muammar Qadhafi, Sirte, and its inhabitants were marginalised and stigmatised following the fall of the regime in October 2011. Left devastated after weeks of shelling and street fighting, the city was still regarded by the new authorities as a stronghold of former regime supporters and the symbol of the ‘defeated’ in the civil war.